"Memories of Birdland"

Memories of Birdland

By David Scardino

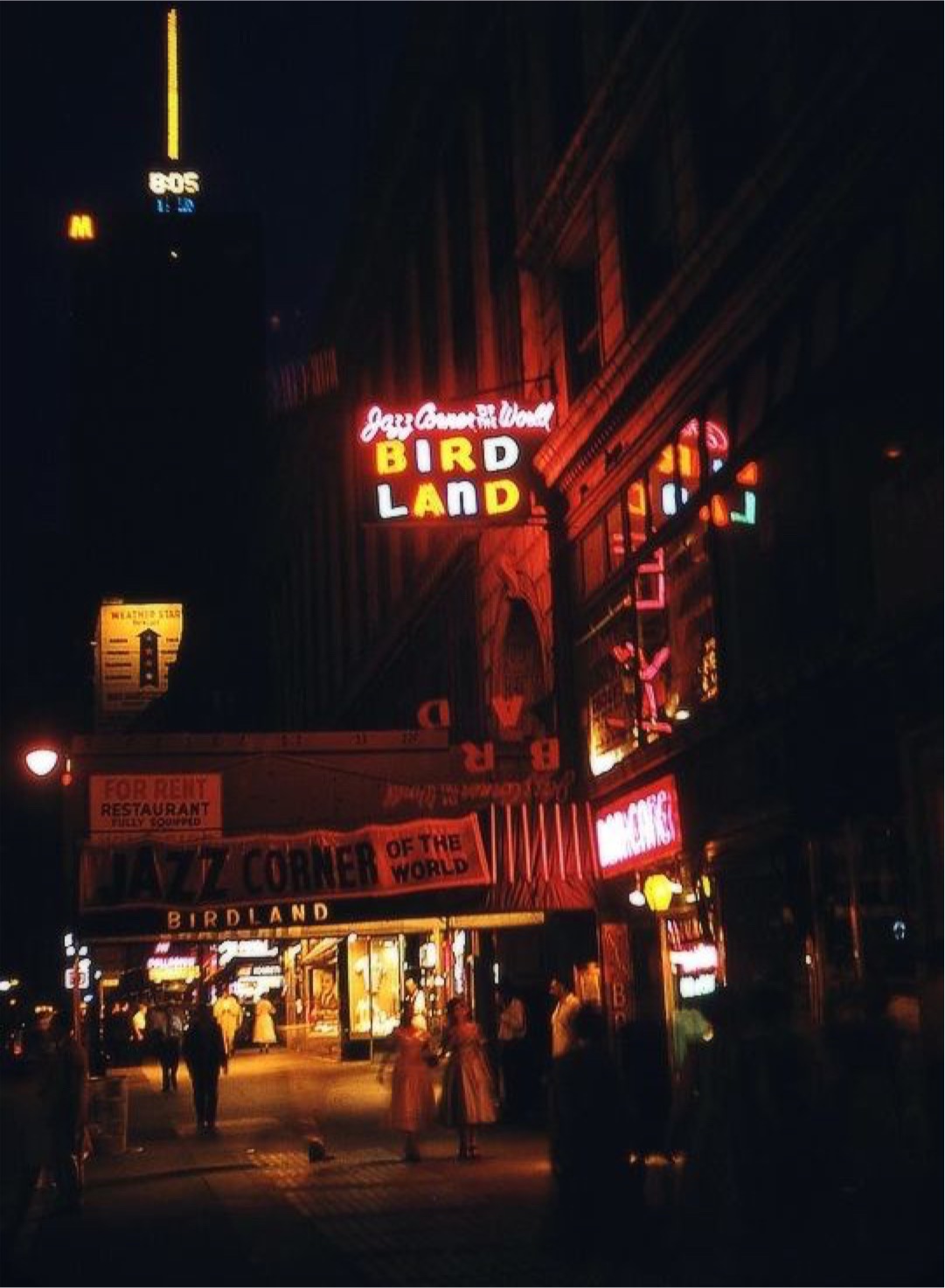

These very subjective memories are prompted by my belief that Birdland—and that’s New York City’s original Birdland, “The Jazz Corner of the World,” between 52nd and 53rd Streets on the east side of Broadway—was unique among Manhattan’s eleven full time jazz clubs in the late-1950’s/early-1960’s. What made Birdland different was its ability to present cutting edge musical excitement in a totally relaxed environment.

My very first memory of Birdland was not mine, but my professional musician parents, and it wasn’t a good one.

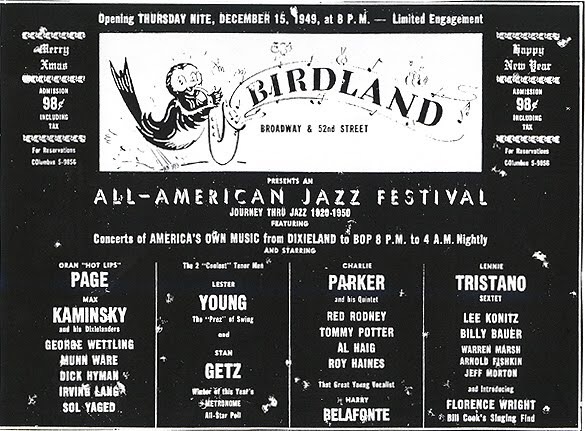

Not long after the club opened in 1949 they went to hear the great tenor saxophonist Lester Young and had their night ruined by (what they called) “Beboppers” loudly putting Lester down. This was especially ironic since Young was the primary influence on Charlie “Bird” Parker, an avatar of Bebop.

It would be a long time before my parents returned to Birdland. But they and we will get there . . . eventually.

Setting the scene for my memories of Birdland is a montage of images:

-

Broadway, glittering, looking south from 53rd Street, the club mid-block on the left side of the street.

-

Birdland’s street-facing entrance, a standing signboard next to the door advertising the night’s bill.

-

The top of a stairwell just inside the club, ticket booth to the right.

-

A view down the stairs.

-

The view from the bottom of the stairs looking towards the bandstand: slightly to the right, tables packed with patrons extend to the bandstand; to the left of the tables is “the bullpen,” three rows of chairs, all filled, separated from the tables by a railing; to the left of the bullpen is the well-populated bar.

-

Finally the bells of three horns: trumpet, tenor sax and trombone.

Then the EXPLOSION! The loud and furious energy of the music, the three horns playing a fiery unison line stoked by a red-hot piano-bass-drums rhythm section. And with that, I’m immersed in the excitement of the greatest place ever to listen to jazz. I say the greatest because for all that surging kinetic energy, Birdland was at the same time a totally relaxed scene. You paid the $2 admission fee at the ticket booth, went downstairs, and grabbed a chair in the bullpen. You could stay all night and never spend another dime. And no one would ever bug you about it. Among Manhattan’s pre-Beatles era jazz clubs this was unique.

True, you couldn’t get decent Italian food like you could at the Half Note or the Five Spot, but you also wouldn’t be slammed together with other patrons via financially profitable, maximized seating as you would at The Village Gate. (Of course, the Gate was the only place in NYC you could see Horace Silver, so there is that.) You also wouldn’t find yourself gouged because you didn’t look like the hippest cat in town as you would at the Village Vanguard (and talk about cheek to jowl tables!).

All that said, you never ever wanted to be in Birdland with the lights up because it took away from the magic of the place. But the acoustics . . . The Modern Jazz Quartet worked the club without amplification!

And that was the key: it was talent that made Birdland the place to hear jazz. In addition to the MJQ, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Art Blakey & the Jazz Messengers, the Cannonball Adderley Quintet (then Sextet), Dizzy Gillespie, the Gerry Mulligan Quartet (and Concert Jazz Band), Charles Mingus’ Jazz Workshop, the bands of Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Maynard Ferguson and Woody Herman all took the bandstand.

Those were just the Tuesday through Sunday headliners. Each bill usually consisted of three bands, each doing two sets per night. Budgetary considerations occasionally led to a comedian in place of one band. The time I saw that happen the comedian was a young and then unknown Flip Wilson working very “blue.”

Monday nights were reserved for “All-Star Sessions.” It was a Monday when, not knowing about the sessions or much else about the club, I made my first visit. At the entrance was a signboard topped by “The Griffin-Davis All-Stars.” I couldn’t believe my luck: first time out of the box and I’m going to see Miles! Once inside, I learned Griffin was Johnny Griffin and Davis was Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, co-leading a two tenors plus rhythm group. It turned out to be a great lesson as my disappointment was quickly replaced by the joy and excitement of a first-class jazz set. Live and learn!

What I didn’t learn then and wouldn’t for months was that being fifteen years old I should have been seated in “the bleachers,” a section at the back of the club reserved for those below the then legal drinking age of eighteen. My guess is that because I was already just about fully grown I was never stopped. I didn’t even realize I should have been until one night many visits later when, behind a group who when queried admitted to being under eighteen, I watched them herded to the bleachers. The light bulb went on, I kept my mouth shut, and fortunately never ever spent time in the bleachers.

Despite a jazz wag’s definition of an “All-Star” as anyone not in a working band, the musicians usually featured on Monday nights were up-and-coming artists; some of the earliest gigs performed by the John Coltrane Quartet were Mondays at Birdland. Then there were in-demand studio pros like trombonist Jimmy Cleveland, a monster player who led various sized ensembles on a much too rare basis. Vacation time for the Basie band often meant sidemen Al Grey (trombone) and Billy Mitchell (tenor sax) fronting a great sextet.

There was even a Monday sub-genre: “event” nights such as sessions sponsored by drum manufacturer Gretsch featuring masters such as Art Blakey, Philly Joe Jones, Charlie Persip and Elvin Jones playing in various combinations and often blurring the line between performance and clinic. For young aspiring drummers (and I was one), these were master classes.

Despite close ties between Birdland and Roulette Records, by the early 1960’s Monday nights often felt like Blue Note Records writ live, the stage graced by label regulars such as Lee Morgan, Hank Mobley, Joe Henderson and Kenny Dorham.

No memory of Birdland would be complete without William Clayton “Pee Wee” Marquette, the club’s cigar smoking, under four feet tall “host.” Always in tuxedo or tails, he acted as emcee, lighting director and guardian of the gate, i.e., wrangling under-eighteen year olds to the bleachers.

(Lester Young, Guy Warren, Pee Wee) (William Clayton "Pee Wee" Marquette 1914-1992)

For all his duties, it was emceeing for which Pee Wee was legendary (and not always for the best of reasons). He would announce the personnel of each band from a list written on the inside of a book of matches. No problem if it was the Oscar Peterson Trio or The Three Sounds, but he’d be reading off the same little matchbook when it was the Count Basie band (sixteen strong) or Gerry Mulligan’s troup (thirteen pieces). How he managed to shrink a big band roster to the inside flap of a matchbook was beyond me.

A few years after I began going to the club, I heard through the musicians’ grapevine that Pee Wee expected tips for his announcing chores and when he didn’t get them he’d mangle the offender’s name. The funniest victim, as reported to me—I didn’t hear it myself—was the bassist Teddy Kotick who, with Pee Wee’s elocution, became “Teddy Kotex.”

And while it was probably easier to slip Pee Wee a five than hear your name mangled every night, there were people he didn’t mess with. Two come to mind: Dizzy Gillespie, who at the end of a set, when the lights came back up, would be on his knees doing a perfect imitation of Pee Wee’s gravelly voice and idiosyncratic diction.

The other person who got the upper hand on Pee Wee was Miles Davis. In 1964, his quintet, with Sam Rivers on tenor, was Birdland’s first booking following a several weeks closure for a thorough renovation. The upgrades included a new sound system featuring slender microphones that sat, seemingly unsecured, on their stands. Having finished his solo, Miles, attempting to reposition the mic for Rivers, was not having much luck. Futzing around for a couple of minutes before reaching his limit, he then dropped the mic down the bell of Sam’s tenor. The result was total distortion at ear-splitting volume. Miles coolly (what else) walked off stage. Rivers and the band (being positioned behind the speakers) kept playing while Pee Wee set a land speed record racing to the stage to set things right. Most of the crowd found it funny; Pee Wee did not.

Though not as visible as Pee Wee, Oscar Goodstein, a part owner, was usually on the scene, often tending the bar. You can see him, standing behind Pee Wee, in the center of the photomontage on the cover of the vinyl version of Art Blakey’s “A Night In Birdland, Vol. 2” on Blue Note. (The same recordings also feature Pee Wee’s intros.)

I can only remember having one conversation with Goodstein, in 1963, recommending that he book Woody Herman’s great band featuring Sal Nistico and drummer Jake Hanna. Sneering, he fluffed me off with: “They’ll never draw in my club!” The following New Year’s Eve, the bill was topped by Woody and the band and the line was around the corner. (My “victories” in the world of jazz have been few and far between, but that was one.)

Living in a Queens neighborhood where the last bus from the subway was at one a.m., and hoping to maximize my music intake, I tried to get to the club on the early side. If the first of the three bands started on time, about nine, I could usually see the complete, three band bill and make the last bus. If I didn’t, it was a long walk (great and ultimately successful motivation for saving to buy a car and eliminating the issue).

While that original time constraint was a drag, there were bonuses to arriving early. First, I could pretty much choose where in the bullpen to sit, which was very important since as an aspiring drummer I always wanted to be as close to the drum kit as possible, preferably with an unobstructed view. If the drums were center stage, as they almost always were when the leader was Art Blakey or Max Roach, my view was blocked. Thankfully, however, enough bands stationed the drummer stage right, enabling the continuation of my percussion studies.

My two favorite “instructors” were Mel Lewis, with the Gerry Mulligan Concert Jazz Band, and Philly Joe Jones, drummer with Miles Davis’ first great quintet and a frequent Birdland performer. Lewis played as creatively and tastefully as anyone I’d ever heard yet with no diminution of power. But Philly Joe, my first true influence, never seemed to miss a thing, every one of his stick and pedal shots squarely in the pocket. He was, as a musician friend of mine observed, “a machine.”

Miles Davis placed drummer Tony Williams in the middle and to the back of the bandstand, probably a good thing for me since when I finally did get a look at the technique of this singular and truly revolutionary musician—he changed the very sound of the instrument and the music—I wanted to pack my drums with dynamite and blow them up. (That look was from the mezzanine of Philharmonic Hall at a Lincoln’s Birthday concert in 1964. The complete two hour plus concert is on discs four and five of the Columbia Legacy set “Seven Steps: The Complete Columbia Recordings of Miles Davis 1963-1964.”)

Another bonus of early arrivals at Birdland was the increased chance I might actually interact with one of my musician heroes. It happened once and was with Dizzy Gillespie, fitting since it was his solo on “Night in Tunisia” (with his mid-1950’s big band) that put me solidly on the jazz track I’ve been on ever since.

Very fortunately, I had a cousin, Bill Mulligan, who was an NYPD detective and had recently recovered Dizzy’s famous bell-tilted-up trumpet after it had been stolen. Finding myself next to Diz at the men’s room sink, and having heard the story a few weeks earlier, I identified myself as Mulligan’s cousin. Dizzy boomed out a huge greeting along with admiration for my cousin. He then said if I wanted anything to let him know. Thrilled just to have spoken with him, I didn’t push my luck.

(Many years later, another cousin told me the real story: the horn hadn’t been stolen but lost in a card game. Embarrassed, Dizzy queried a cop friend who reached out to my cousin who, using his connections, got the horn back and revealed the true story only to his immediate family plus, of course, my parents because they were professional musicians.)

Quite a few of my other Birdland memories play out like short scenes:

-

Philly Joe Jones throwing his sticks at WADO radio d.j. Symphony Sid Torin (who broadcast from the club every Friday night) when Sid was trying to get Philly’s sextet off stage and the Gerry Mulligan Quartet (with Bob Brookmeyer) on. Mulligan and Brookmeyer, in sympathy, played with Philly’s band. Sid shrugged.

-

Seeing Mingus’ Jazz Workshop, but with Henry Grimes playing bass and Mingus playing piano! (Much, much later Mingus would say he was dissatisfied with every piano player he ever worked with until Jaki Byard.)

-

Another Mulligan, this time his Concert Jazz Band with Clark Terry’s great solos and the band’s swirling and swinging sax ensemble sections that made you want to stand up and cheer.

-

Then there were the smaller, more personal kind of moments: Freddie Hubbard, just beginning his career as a leader, squelching an overly loud drummer with a sideways “fish-eye”; Charles Lloyd, when he was with Cannonball, executing a pirouette to get off stage for a number on which he didn’t play; Joe Zawinul, also with Cannonball, rotating his head in larger and larger circles while soloing and just missing hitting the keyboard.

-

And to this day I marvel at how deftly Dizzy, Cannonball and Blakey handled audiences. (In the early 1970’s, at Ali’s Ally, downtown, I would discover what a great stand-up comedian Philly Joe Jones could be.)

I can really only remember one regret: never seeing Thelonius Monk at Birdland (or, actually, at any club). I did see him several times in concert but somehow, maybe just bad timing, never in an intimate setting. (Much later I learned he had been banned from Birdland for burning the wood on a brand new piano, but that was back in the early 1950’s.)

Now, as promised, the overcoming of my parents’ anti-Birdland prejudice: it happened well into my years of patronizing the club when all my raving about all the great music finally wore them down and they let me take them to hear Gerry Mulligan and his big band. They loved it! And they even had a friend in the band, so there was that, too.

Many, many years later, they paid a visit to the “new” Birdland on 44th Street to see the late Kenny Rankin, a family friend. They had a great time, but my father made sure I, now living in California, knew that the bill that night (which included dinner) came to more than a hundred bucks per person. “A bit more than the two dollars you had to pay to sit in the bullpen, right?” he asked. I could hear his smile and feel the weight of all those memories and the passing of all those years all the way cross-country.