Kant's Genius Art Machine

“In most fields of philosophy, one must be content with hypothetical examples, but philosophers of the arts have the distinct advantage of being able to produce actual examples to illustrate their theories (or refute others).”

Andrew Kania in "Silent Music," p. 21

Contents

Discussion[edit]

Kant on Art[edit]

Immanuel Kant on Art[edit]

In his book, The Philosophy of Art: An Introduction, Theodore Gracyk (b. 1958) gives a compelling reading of Kant's views on art that appear relevant to jazz. Or, rather, jazz appears relevant as possible and actual counter-examples to Kant's views relating to art production, genius, and genius's abilities to create art.

A striking opening overview of Kant's position on art as formulated in The Critique of Judgment has Gracyk explaining that “Kant's "Critique of Aesthetic Judgment" can be read as a modernization of the Platonic thesis that artistic creativity involves a unique state of mind.” Gracyk provides an overview of Kant's positions respecting definitions of art when commenting that Immanuel Kant believed that “works of genius require the interplay of different mental abilities” and that Kant proceeds by “codifying the idea that imagination is the key to genius.”[1]

Kant believes that art education “plays a central role in correcting the excesses of genius,” explains Gracyk because:

“Kant proposes that art's primary function is to stimulate thinking about ideas, by producing aesthetic ideas or original images that promote imaginative associations with a variety of related concepts which therefore communicate indirectly what we cannot say directly.” (bold not in original)

Theodore Gracyk, Ch 3. "Meaning and Creativity," 3.2 Kant on genius, in The Philosophy of Art, 2012.

“Genius is the talent (or natural gift) which gives the rule to Art. Since talent, as the innate productive faculty of the artist, belongs itself to Nature, we may express the matter thus: Genius is the innate mental disposition (ingenium) through which Nature gives the rule to Art.” (bold not in original)

Immanuel Kant in The Critique of Judgment, §46

“For every art presupposes rules by means of which in the first instance a product, if it is to be called artistic, is represented as possible. But the concept of beautiful art does not permit the judgement upon the beauty of a product to be derived from any rule, which has a concept as its determining ground, and therefore has at its basis a concept of the way in which the product is possible. Therefore, beautiful art cannot itself devise the rule according to which it can bring about its product. But since at the same time a product can never be called Art without some precedent rule, Nature in the subject must (by the harmony of its faculties) give the rule to Art; i.e. beautiful Art is only possible as a product of Genius.” (bold and bold italic not in original)

Immanuel Kant in The Critique of Judgment, §46

“We thus see (1) that genius is a talent for producing that for which no definite rule can be given; it is not a mere aptitude for what can be learnt by a rule. Hence originality must be its first property. (2) But since it also can produce original nonsense, its products must be models, i.e. exemplary; and they consequently ought not to spring from imitation, but must serve as a standard or rule of judgement for others. (3) It cannot describe or indicate scientifically how it brings about its products, but it gives the rule just as nature does.” (bold and bold italic not in original)

Immanuel Kant in The Critique of Judgment, §46

INSTRUCTIONS[edit]

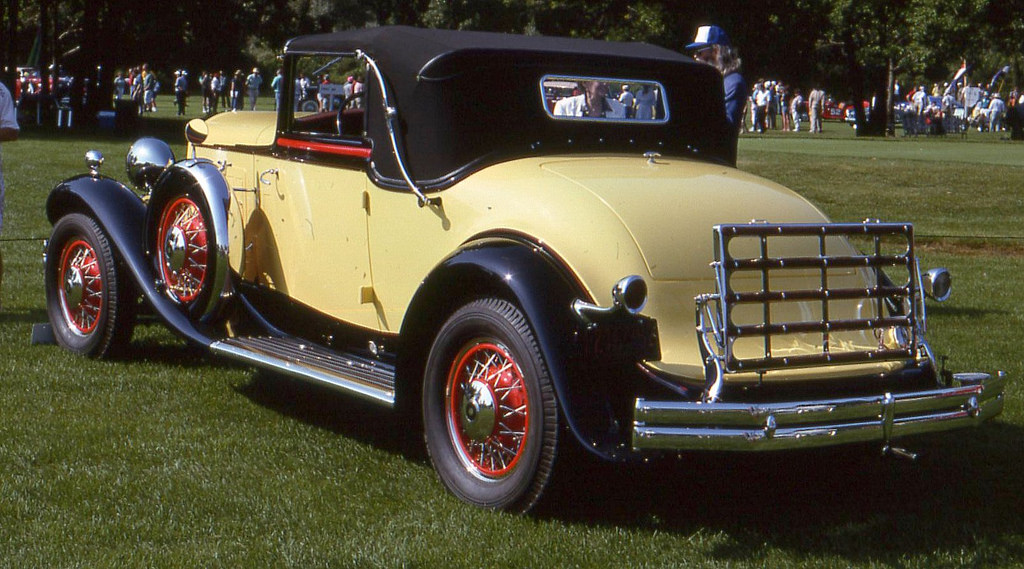

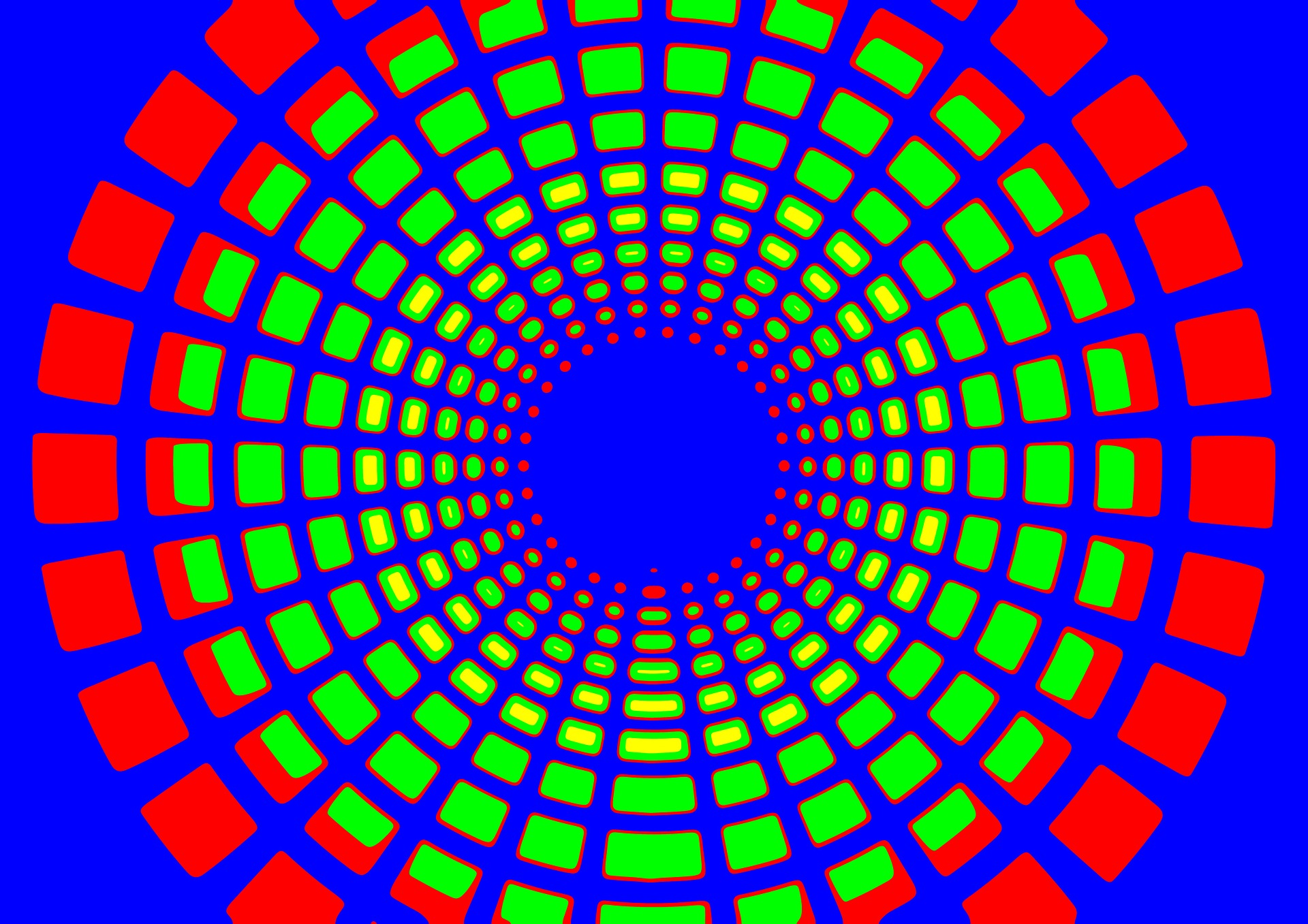

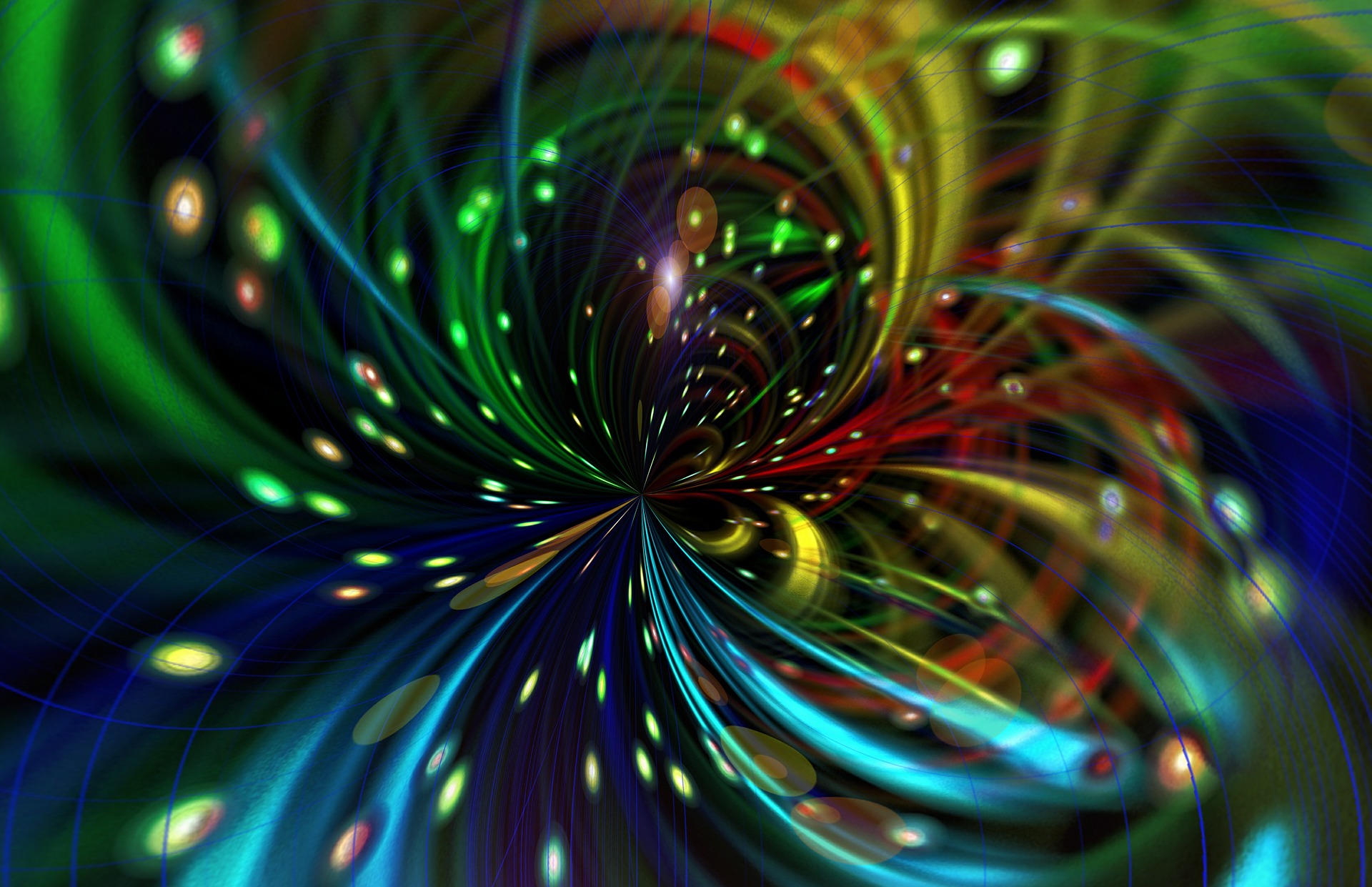

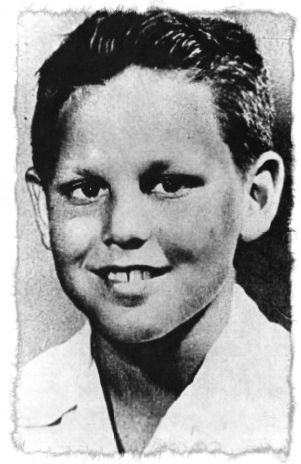

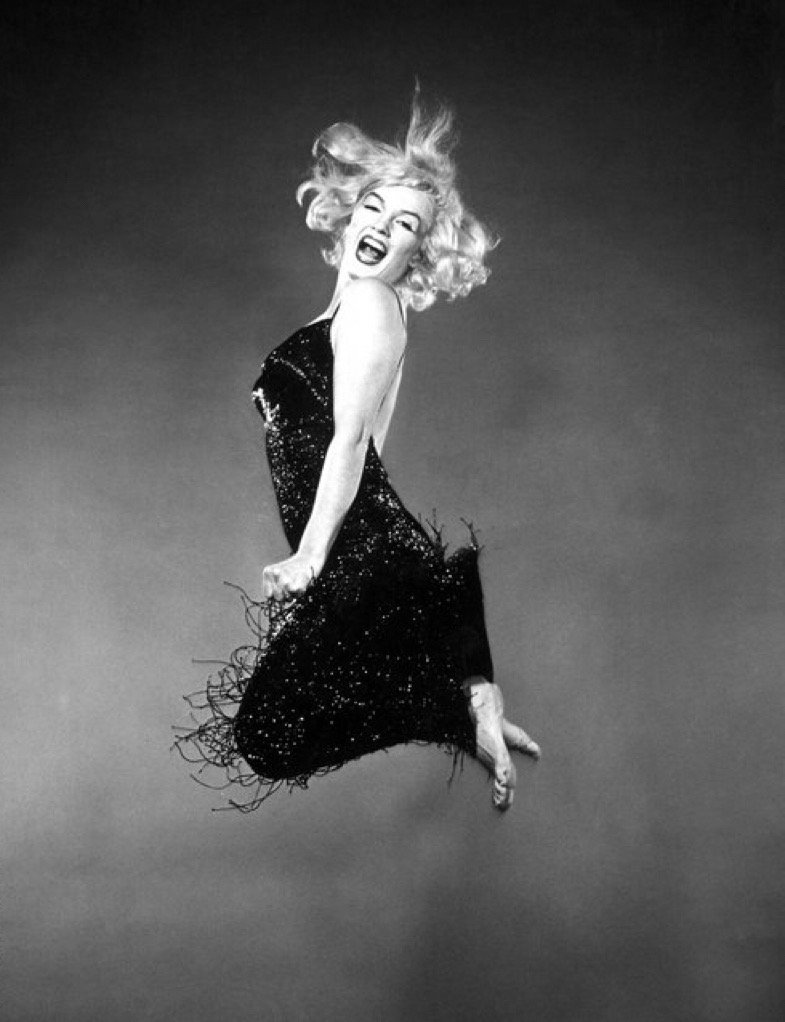

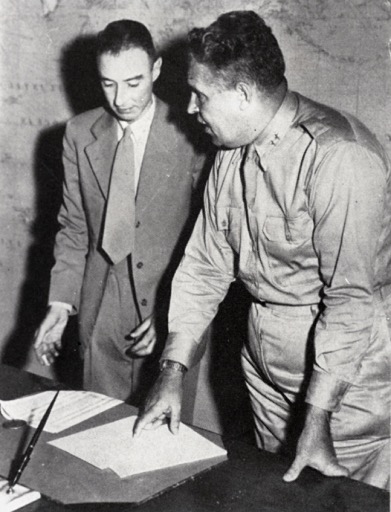

- First, begin by clicking in the first row on any one of the three "Choose A1, B1, or C1" selections below following the instructions. Do not click on the pictures, but on the word "Choose" with a letter and number.

- Choosing one jumps you to your next set of choices. Repeat.

- If you get stuck repeating the same grouping of images, then make a different choice than before.

- This version of the Genius Art Machine is a limited edition prototype filling in for a proper functioning machine that would never repeat image groupings.

- OF SPECIAL NOTE: Kant's Genius Art Machine was intentionally designed so that each choice chosen should lead you to a new previously unseen panel of three image choices. Because of time constraints to devote to such a project, the PoJ.fm machine used has only thirty (30) plates of three choices. In principle, even on this machine, it is possible to make choices such that the next twenty-nine selections after the first one are all new plates never seen before. In actual practice, the typical number of selections before a panel reappears is five to ten selections. Sometimes the original panel you began with does not repeat, but one gets into a cycle of only a couple of panels that start to cycle through to each other. Because the number of choices is being made by the user, the number of choices made using any order or pattern typically repeats a plate of three choices within five to ten moves. As a challenge, see if you can make more than ten choices before you are returned to a panel (of three choices) that you have previously seen. An excellent number to accomplish is more than sixteen selection choices before repeating a panel.

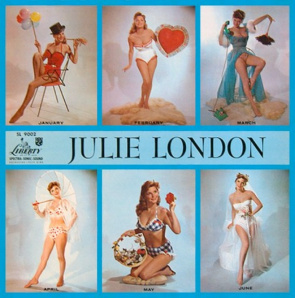

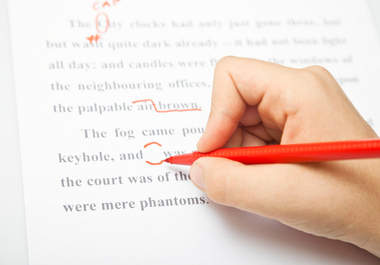

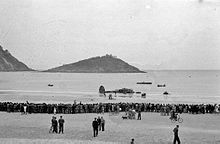

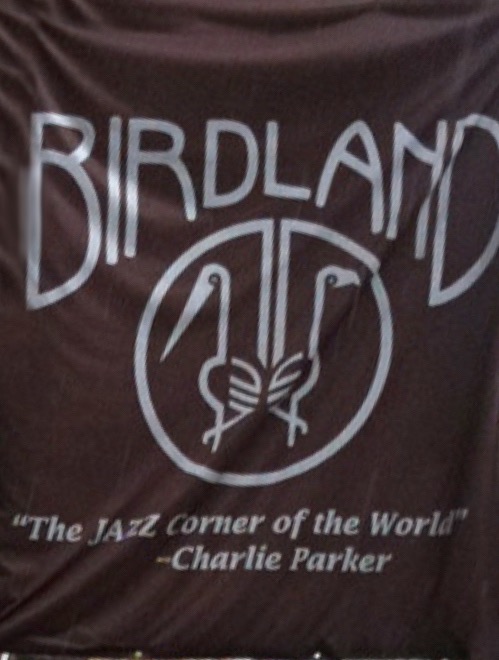

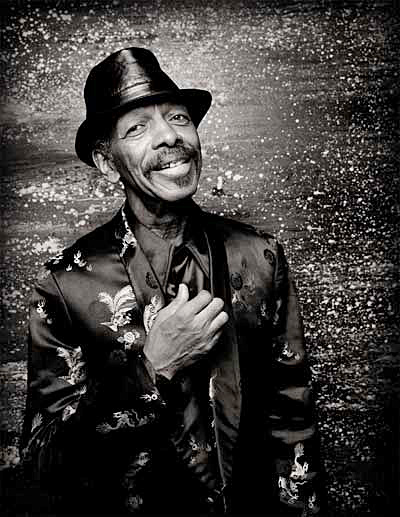

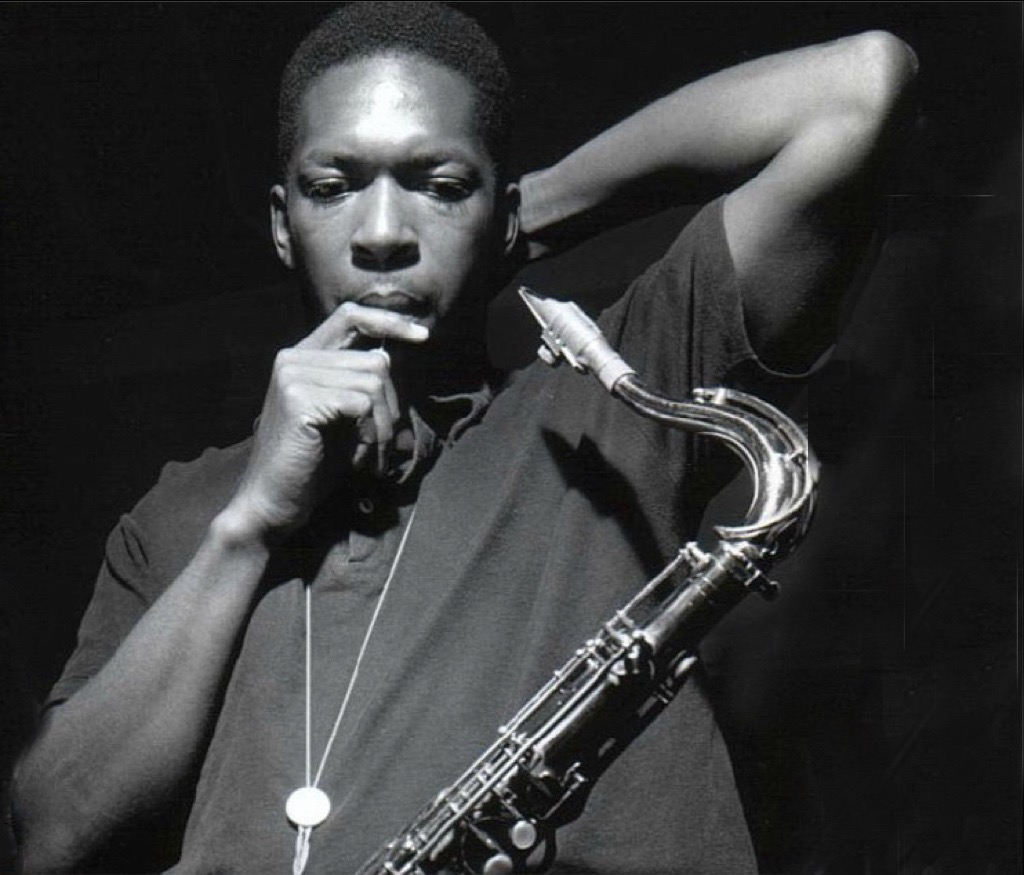

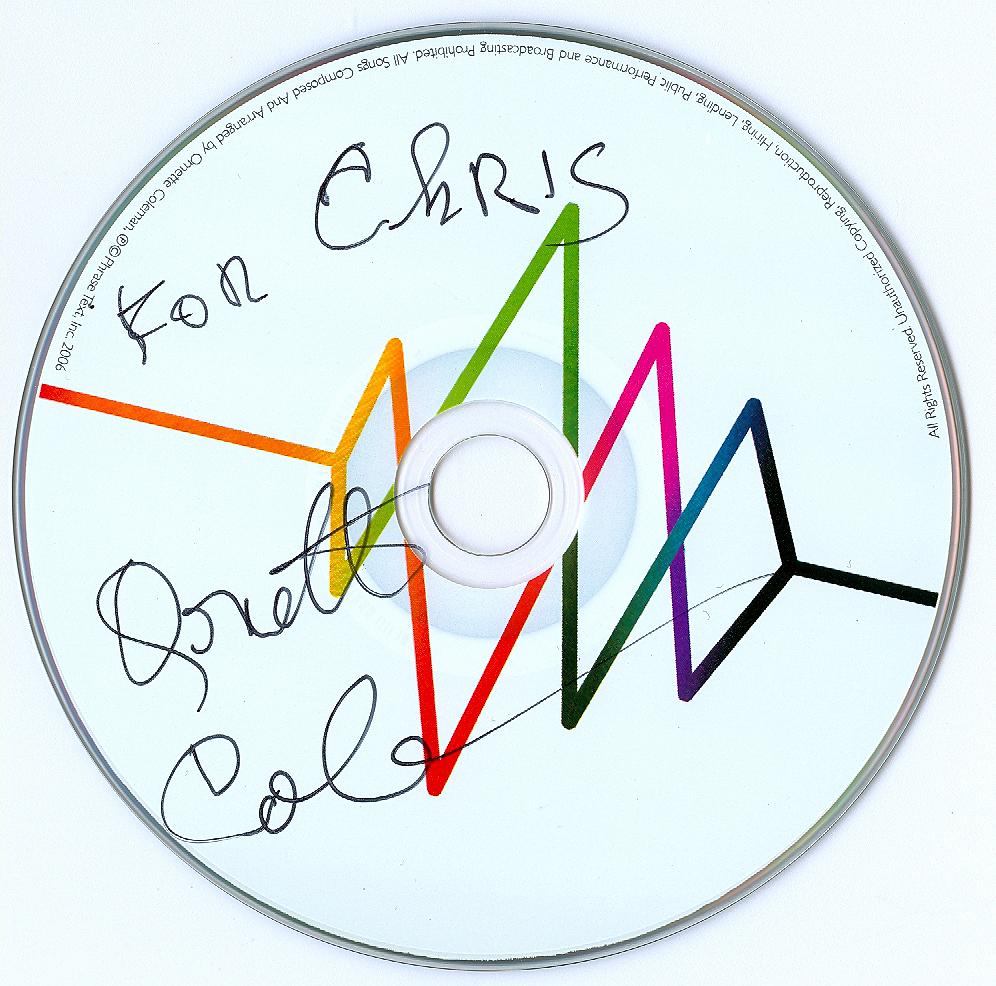

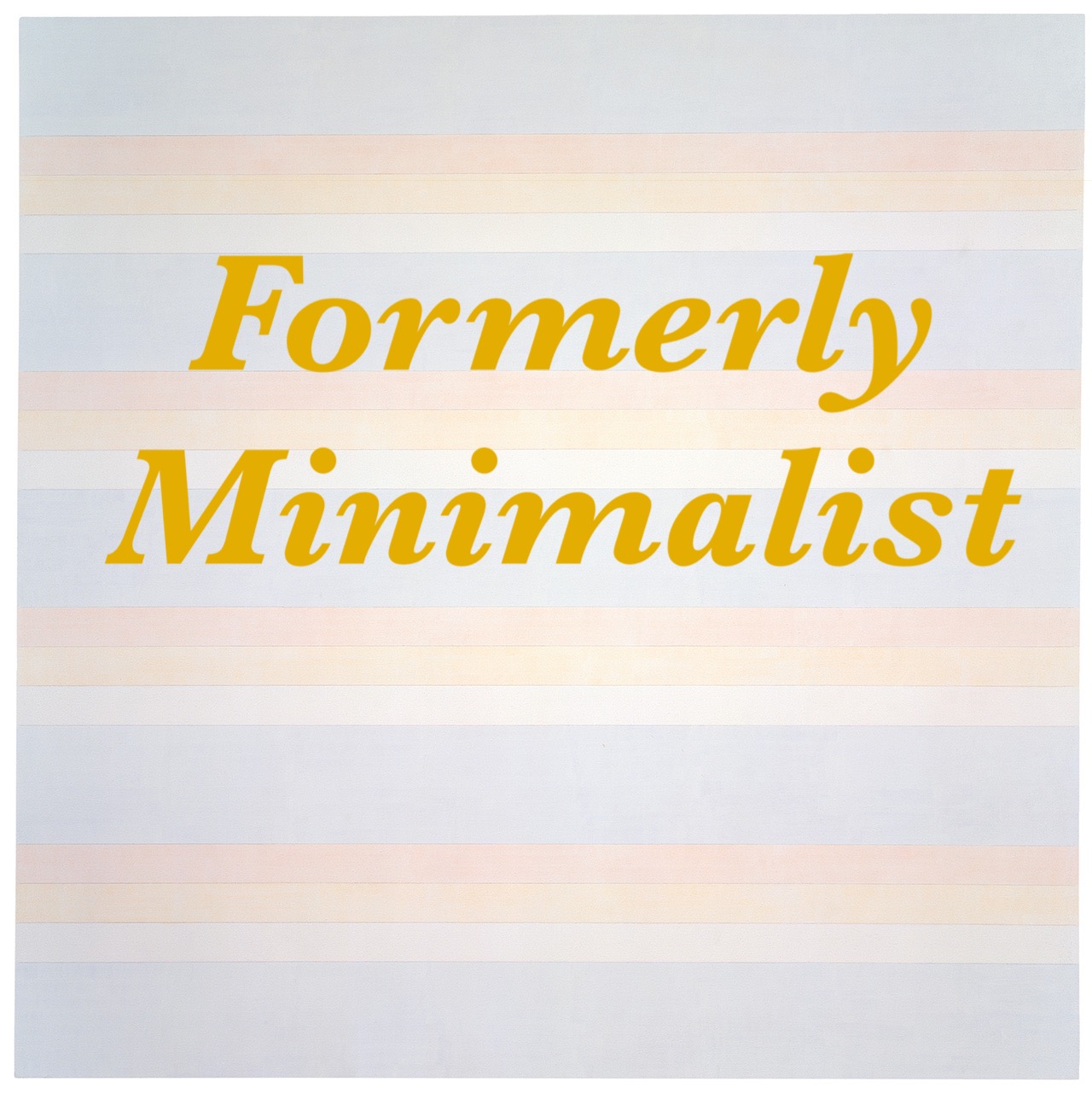

- As you proceed, contemplate the various design aspects seen and any other aesthetic features observed and what you are stimulated to think about and experience from the seen images during your tour of the Genius Art Machine.

Why the Genius Art Machine is not a good work of art[edit]

➢ How should one go about judging when an artwork is good artwork?

Boy, these are some humdingerish difficult questions to answer, but let's give it a shot anyway.

Begin with the observation that there does exist a range of goodness and badness in artworks. The proof of this is that (A) artworks exist and (B) they are not all equally good in terms of artistic merits as each other. Artwork's goodness or badness comes in degrees. Hence, since there is a range of bad to good to great artworks one needs criteria upon which to base objective judgments as to an artwork's merits or demerits.

➢ What candidates are there for providing the basis for aesthetic judgments of goodness and badness of artworks? There are many possible as well as eminently reasonable candidates.

Start with money. Some artworks bring more money at auction than others. While there are certainly exceptions in the artworks of you get what you pay for still holds true on many occasions. A $50,000 dollar painting likely has more aesthetic properties of goodness, however these get determined in the long run, than a painting valued at only $1.00. Of course there can be exceptions such that you might rather have your recently deceased daughter's $1.00 drawing than a $50,000 dollar Picasso. Is it believable that over the years Biff maintains his daughters drawing is a better artwork than the vastly more expensive Picasso? If he does, then we have a counter-example to monetary values always indicating which artwork is better than another.

But we were not concerned with relative comparisons of which artwork is superior or inferior, but rather what makes one artwork be good artwork?

One can turn to various scales with protocols (i.e., procedures) that when carried out determine whether something has a characteristic or not and to what degree. For example symmetry is often thought relevant when making aesthetic judgments of goodness or badness. One can objectively determine whether this object or that object has more symmetry with respect to itself.

The genius art machine (GAM) does accomplish what Kant claims great artwork achieves because it "promotes imaginative associations with a variety of related concepts which therefore communicate indirectly what we cannot say directly” and stimulates viewers to have such artistic ideas. However, no one thinks that cycling through a variety of pictures by itself makes the GAM be a great work of art.

The Genius Art Machine Counter-examples Immanuel Kant's Definition of Art[edit]

(1) Kant claims that art's primary function, according to Theodore Gracyk (in his The Philosophy of Art, p. 46) is to “stimulate thinking about ideas because artworks produce aesthetic ideas or original images that promote imaginative associations with a variety of related concepts which therefore communicate indirectly what we cannot say directly.”

(2) The Genius Art Machine (GAM) satisfies each and every requirement Kant requires of art 🖼 . As a user of GAM one when paying attention during its use will be stimulated to think about aesthetic ideas when making choices of which image to click on next, one will observe original images that will definitely promote imaginative associations with a variety of related concepts and the images will suggest many things not immediately conveyable all in words thereby achieving Kant's requirement that art can communicate indirectly what art admirers might not say directly (immediately, or ever).

CONCLUSION: The Genius Art Machine does what Kant claims art does by stimulating the formation of aesthetic ideas of the correct type, but the Genius Art Machine is not a good artwork. Therefore, Kant's definition of art is not a sufficient condition for good artwork.

Kant's Genius Art Machine[edit]

NOTE: Click on the words Choose A, B, or C and not on the pictures.

1[edit]

| Choose A1 | Choose B1 | Choose C1 |

|---|---|---|

A1:  |

B1:  |

C1:

|

2[edit]

| Choose A2 | Choose B2 | Choose C2 |

|---|---|---|

A2:  |

B2:  |

C2:

|

3[edit]

| Choose A3 | Choose B3 | Choose C3 |

|---|---|---|

A3:  |

B3:  |

C3:

|

4[edit]

| Choose A4 | Choose B4 | Choose C4 |

|---|---|---|

A4:  |

B4:  |

C4:

|

5[edit]

| Choose A5 | Choose B5 | Choose C5 |

|---|---|---|

A5:  |

B5:  |

C5:

|

6[edit]

| Choose A6 | Choose B6 | Choose C6 |

|---|---|---|

A6:  |

B6:  |

C6:

|

7[edit]

| Choose A7 | Choose B7 | Choose C7 |

|---|---|---|

A7:  |

B7:  |

C7:

|

8[edit]

| Choose A8 | Choose B8 | Choose C8 |

|---|---|---|

A8:  |

B8:  |

C8:

|

9[edit]

| Choose A9 | Choose B9 | Choose C9 |

|---|---|---|

A9:  |

B9:  |

C9:

|

10[edit]

| Choose A10 | Choose B10 | Choose C10 |

|---|---|---|

A10:  |

B10:  |

C10:

|

11[edit]

| Choose A11 | Choose B11 | Choose C11 |

|---|---|---|

A11:  |

B11:  |

C11:

|

12[edit]

| Choose A12 | Choose B12 | Choose C12 |

|---|---|---|

A12:  |

B12:  |

C12:

|

13[edit]

| Choose A13 | Choose B13 | Choose C13 |

|---|---|---|

A13:  |

B13:  |

C13:

|

14[edit]

| Choose A14 | Choose B14 | Choose C14 |

|---|---|---|

A14:  |

B14:  |

C14:

|

15[edit]

| Choose A15 | Choose B15 | Choose C15 |

|---|---|---|

A15:  |

B15:  |

C15:

|

16[edit]

| Choose A16 | Choose B16 | Choose C16 |

|---|---|---|

A16:  |

B16:  |

C16:

|

17[edit]

| Choose A17 | Choose B17 | Choose C17 |

|---|---|---|

A17:  |

B17:  |

C17:

|

18[edit]

| Choose A18 | Choose B18 | Choose C18 |

|---|---|---|

A18:  |

B18:  |

C18:

|

19[edit]

| Choose A19 | Choose B19 | Choose C19 |

|---|---|---|

A19:  |

B19:  |

C19:

|

20[edit]

| Choose A20 | Choose B20 | Choose C20 |

|---|---|---|

A20:  |

B20:  |

C20:

|

21[edit]

| Choose A21 | Choose B21 | Choose C21 |

|---|---|---|

A21:  |

B21:  |

C21:

|

22[edit]

| Choose A22 | Choose B22 | Choose C22 |

|---|---|---|

A22:  |

B22:  |

C22:

|

23[edit]

| Choose A23 | Choose B23 | Choose C23 |

|---|---|---|

A23:  |

B23:  |

C23:

|

24[edit]

| Choose A24 | Choose B24 | Choose C24 |

|---|---|---|

A24:  |

B24:  |

C24:

|

25[edit]

| Choose A25 | Choose B25 | Choose C25 |

|---|---|---|

A25:  |

B25:  |

C25:

|

26[edit]

| Choose A26 | Choose B26 | Choose C26 |

|---|---|---|

A26:  |

B26:  |

C26:

|

27[edit]

| Choose A27 | Choose B27 | Choose C27 |

|---|---|---|

A27:  |

B27:  |

C27:

|

28[edit]

| Choose A28 | Choose B28 | Choose C28 |

|---|---|---|

A28:  |

B28:  |

C28:

|

29[edit]

| Choose A29 | Choose B29 | Choose C29 |

|---|---|---|

A29:  |

B29:  |

C29:

|

30[edit]

| Choose A30 | Choose B30 | Choose C30 |

|---|---|---|

A30:  |

B30:  |

C30:

|

NOTES[edit]

- ↑ Theodore Gracyk, Ch. 3 "Meaning and Creativity," 3.2 Kant on genius, The Philosophy of Art: An Introduction (Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2012).