Ontdef2. Arguments for the impossibility of defining jazz

Generally speaking, in the history of both—jazz in general, and jazz scholarship in particular,—mostly one finds an extreme pessimism regarding the possibility of coming up with an acceptable definition of or for jazz.

Contents

- 1 Pessimism About Defining Jazz

- 2 Critique of Complexity, Multiple Styles and Challenge Arguments For the Impossibility of Defining Jazz

- 3 Vehicle Counter-Example

- 4 Is the Definition of Jazz Subjective?

- 5 Why jazz cannot be defined as black music

- 6 Robert Kraut on Problems With Defining Jazz

- 7 What is the Data of Jazz?

- 8 Problems with Definitions

- 9 What determines jazz if human conceptions do not?

- 10 NOTES

Pessimism About Defining Jazz

Here's a brief survey of some of the naysayers:

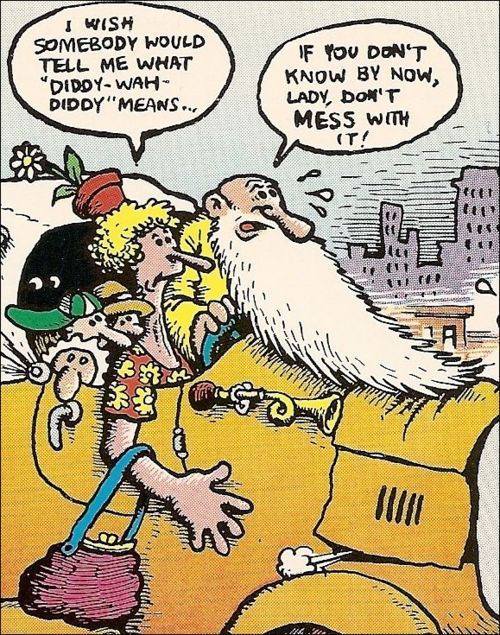

- When Fats Waller (1904-1943) was asked to define jazz, he allegedly warned, "If you have to ask, don’t mess with it." as quoted in How To Listen To Jazz by Ted Gioia.

- Loius Armstrong's (1901-1971) response to the question of defining jazz was to warn that "If you have to ask, what jazz is, you'll never know."[1]

- Scott Deveaux (b. 1954) argues that one should avoid defining jazz “in musical terms" because:

“Defining jazz is a notoriously difficult proposition, but the task is easier if one bypasses the usual inventory of musical qualities or techniques, like improvisation or swing (since the more specific or comprehensive such a list attempts to be, the more likely it is that exceptions will overwhelm the rule).”[2]

- Thomas E. Larson (b. 1955) points out that "jazz is difficult to define, especially today, because it is performed in so many styles and its influence can be heard in so many other types of music [making] it nearly impossible to come up with a set of hard and fast rules.”[3]

Of course this sounds like the Multiple Styles argument which gets refuted below.

- In the Encyclopedia Brittanica entry on jazz Gunther Schuller (1925-2015) writes of the futility of trying to define jazz because of its constant evolution:

"Any attempt to arrive at a precise, all-encompassing definition of jazz is probably futile. Jazz has been, from its very beginnings at the turn of the 20th century, a constantly evolving, expanding, changing music, passing through several distinctive phases of development; a definition that might apply to one [genre might not apply to another]."

As a potential argument, Schuller's remarks are a combination of the Multiple Styles argument ("jazz has evolved different styles") and the Challenge Argument ("no one could find a definition that applies to all jazz styles"). Both of these arguments are refuted below.

Even such stalwart defenders of jazz's metaphysics as James O. Young and Carl Matheson are reluctant to take on trying to define jazz. They put it this way:

"We have no intention of defining a phenomenon as complex and multifarious as jazz. It would be difficult, indeed, to come up with a definition that embraces Dixieland, Ragtime, Bebop, cool jazz, free jazz, and the many other styles. We will simply assume that readers have a rough-and-ready conception of jazz: they know jazz when they hear it."[4]

If we turn these remarks into an argument, what is that argument? Apparently from the pessimism exuded, if a phenomenon is "complex and multifarious" one should not bother to define it. Furthermore, the task of defining something will be "difficult" if the thing being defined has a "lot of styles."

Critique of Complexity, Multiple Styles and Challenge Arguments For the Impossibility of Defining Jazz

What do these amount to as arguments?

- CMJ: Complexity Argument

- (CMJ1) Anything complex and diverse ("multifarious") cannot easily be defined.

- (CMJ2) Jazz is complex and multifarious.

- (CMJ3) Therefore, jazz cannot be easily defined.

- CMJ: Complexity Argument

CONCLUSION: That jazz is not easy to define doesn't make it any more impossible to determine its definition. So, this doesn't prove jazz cannot be defined.

- (Multiple Styles Argument)

- (S1) Anything with many styles cannot be successfully defined.

- (S2) Jazz has many styles (Dixieland, Ragtime, Bebop, cool jazz, free jazz, etc.).

- (S3) Therefore, jazz cannot be successfully defined.

- (Multiple Styles Argument)

Many theorists object to the possibility of defining jazz by using the Multiple Styles objection. In Listening to Jazz, author Benjamin Bierman[5] commits himself to this position when he writes:

“Even if we had a good definition [of jazz], it would certainly be under a process of continual re-evaluation. Jazz is always headed in unexpected and exciting directions.”[6] (bold not in original)

- (Challenge Argument)

- (C1) There is currently no definition of jazz that has been found (or could be found) that embraces all of the different jazz styles.

- (C2) Jazz cannot be defined.

- (Challenge Argument)

Benjamin Bierman supports the Challenge Argument when he writes:

“Jazz seems to be impossible to define in a way that makes anyone very happy. Countless articles and books have made valiant, valid, and fascinating attempts to define it, yet none are wholly satisfactory.”[6] (bold not in original)

Putting these claims so boldly into premises helps remove the rhetorical power the claims have, and we can just consider the truth of the principles involved. Start with (CMJ1) and ask if it is true. It is obviously false if one believes ANY definitions at all are both possible and actual. Virtually any definition defines a phenomenon that is likely to be "complex and multifarious."

Vehicle Counter-Example

Suppose you think one can define the word "vehicle" as a thing used to transport people or goods, especially on land, such as a car, truck, or cart. Since this was easy to define (however that is measured), yet vehicles are both complex and diverse (i.e., 'multifarious') with many different styles, this refutes the first premises of the Complexity argument and the Multiple Styles argument: namely, (CMJ1) and (S1).

Vehicle styles can include: SUV (sport utility vehicle), truck, sedan, van, coupe/compact, wagon, convertible, sports car, diesel, crossover, electric/hybrid, luxury car, certified pre-owned, and hatchback, to name a few. Each of these diverse and various styles all still falls within the definition for a vehicle. (See Wikipedia: Car classification).

Consider next, the different types of vehicles, because most of the above styles were just automobiles, it is somewhat astonishing how many different vehicle 🚗 types exist. There are certainly more types of vehicles than there are types of jazz. As proof, Wikipedia lists well over a hundred types of vehicles. One would be hard-pressed to come up with over a hundred different types and styles of jazz.

To give some idea of the diversity of possible vehicle types, think about these: motorcycle, eighteen-wheeler, tricycle, moped, scooter, solar-powered vehicle, pogo stick, iceberg, airplane, amphibious all-terrain vehicle, balloon, bicycle, blimp, cable car, and ninety-plus more to go.

CONCLUSION: Yet "vehicle," which has numerous and sundry styles and differences, can still be defined successfully, thereby refuting the Multiple Styles argument opposing any definition for jazz.

In their "The Metaphysics of Jazz," James O. Young and Carl Matheson, while espousing the virtual or practical impossibility of defining jazz in musical terms, nevertheless continue to claim that “readers will still know jazz when they hear it.”[7]

Isn't this last claim impossible? If listeners know jazz, then they can recognize it. If they can recognize it, then there must ALREADY be something that CAN be recognized. Whatever that IS is the content of the definition of jazz!

Even the great music critic Ralph J. Gleason (1917-1975), a founding editor of Rolling Stone magazine and co-founder of the Monterey Jazz Festival, while writing the liner notes to Miles Davis's "Bitches Brew," appears to accept some form of the Multiple Styles argument and a few other intuitions when he writes:

“So be it with the music we have called jazz and which I never knew what it was because it was so many different things to so many different people each apparently contradicting the other, and one day, I flashed that it was music.” (Click on any part of this green quotation to see Gleason's liner notes at the third paragraph)

So, when Gleason says he "never knew" what jazz was because "jazz was so many different things to so many different people," he appears to be accepting some form of the Multiple Styles argument, but with a twist—subjectivity.

Ignoring the subjectivity aspect and focusing on the "jazz is so many different things" component," the Vehicle counter-example argument refutes any reason against the impossibility of defining anything, including jazz, just because it has many styles.

For what is required for a successful definition, see PoJ.fm's Ontdef1. What is a definition?.

Is the Definition of Jazz Subjective?

What is Jazz? by Jason West at All About Jazz also, in effect, believes jazz is impossible to define. He writes:

“Certainly, the question is a highly subjective one. Ask 100 different people, "What is jazz?" and you're likely to get 100 different answers. The debate becomes even more confusing given the fact that the history of jazz is relatively well documented. . . . Why then, less than half a century later, can't we agree on a working definition? Part of the reason is because jazz has always been and remains today a living art form, ever-changing and ever-growing. . . . [Since the 1950s jazz has birthed Bebop, modal jazz, free jazz, incorporated rock, electric instruments, and classical music, and John Coltrane's "sheets of sound" so jazz] exploded and suddenly jazz was all over the place. . . . . At present, it seems that there are almost as many names for jazz as there are jazz groups. Still puzzled? Me too. . . . Once again, each one of us is left with our own purely subjective views on jazz. My guess is that, if asked, even musicians—the men and women who are currently dedicating their life to creating this music—would likely disagree on the meaning of jazz.” (bold not in original)

Let's analyze these remarks. Is the question itself subjective? "Subjective" means based on or influenced by personal feelings, tastes, or opinions, dependent on the mind of an individual's perceptions for its existence.

Merriam-Webster's dictionary on the meaning of "subjective" has this as some of the relevant definitions:

(1) peculiar to a particular individual: personal, e.g., subjective judgments. (2) modified or affected by personal views, experience, or background, e.g., a personal account of the incident. (3) arising from conditions within the brain or sense organs and not directly caused by external stimuli, e.g., subjective sensations. (4) arising out of or identified using perception of one's states and processes.

The question "What is Jazz?" cannot be subjective

Applying these usages of the subjectivity concept, it is evident that it isn't the question that is subjective. The question "What is jazz?" is neither peculiar to a single individual, nor arises from only internal (brain) resources or stimuli, nor identified by one's perceptions, any more than any other question. Would Jason West claim that "What is an electron?" has only a subjective answer? Hardly.

Presumably, what Jason West and Ralph J. Gleason had in mind was that the question's answer was subjective. This is false, too! The answer to the question "What is jazz?" is no more subjective than to "What is an electron?" Neither question's response in any way depends on any individual conscious mental experiences or judgments. Hence, neither the question nor the possible resolutions to it are subjective.

If subjectivity entirely determined the status of everything about jazz, then who could ever believe anything wrong about jazz.

➢ Can you get things wrong about jazz?

Yes, there are many things one could get wrong about jazz. Here's a list:

List of things one could get wrong about jazz labeled with the letter "F" for false, followed below by the true claims numbered with a "T."

If anyone were to believe any of the following claims, they would be wrong about jazz.

- (F1) Jazz derived directly from the classical music of Brahms (1833-1897) and Beethoven (1770-1827).

- (F2) Jazz was created initially in China.

- (F3) Jazz never uses syncopation.

- (F4) Throughout jazz history, there have been more females than male instrumentalists.

- (F5) Jazz and Rock and roll are the same genre of music.

- (F6) The primary timekeepers during jazz performances are never the drummer or bass player.

Can you think of some more false claims regarding jazz? Certainly, you can. Such things are easy to make up, proving that not only does subjectivity not determine the answers about the truth of the claims, but even inter-subjectivity is irrelevant. Even if almost everyone believed any one of these claims, they all would be thinking something false because of historical facts to the contrary.

- (T1) Jazz could not have derived directly from Brahms and Beethoven's classical music because they never made music with a hybridized musical scale incorporating their European diatonic scale with a pentatonic one. Furthermore, as proto-jazz and jazz developed near the turn of the 20th century, it was influenced not by classical music, but rather spirituals, gospel, marches, blues, work songs, call and response choruses, and piano ragtime.

- (T2) Jazz never came from China, but from the United States, especially out of New Orleans.

- (T3) One of jazz's claims to fame is significant use of syncopation.

- (T4) There have been more male than female instrumentalists.[8]

- (T5) Generally speaking, Rock does not use as complex musical structures as jazz. They are different genres.

- (T6) Time keeping usually falls especially on the drummer and bass player, although all musicians need to keep the time while performing.

What then did these people have in mind when referring to subjectivity concerning jazz? It is evident in West's case that he believes people have differing beliefs about jazz, and then what is supposed to follow from that? Again, just because people disagree does not entail that there is not a correct answer. Suppose some people believe the planet Earth is flat, while others believe it roughly spherical. Does it follow the answer to the question, "What is the Earth's shape?" doesn't have a correct answer? Of course not. Similarly, for jazz. Differing opinions about anything does not alter whatever ontological status something really has nor its identity conditions (if it exists at all).

Furthermore, it is somewhat doubtful that there is as much disagreement over the features of jazz that someone might use for a definition. It is not so much that people have differing opinions on jazz's musical characteristics as they disagree over which styles of music using the word "jazz" qualify as such. Many would claim that what is called acid jazz is not really jazz. Others believe free jazz is not jazz, or jazz-rock fusion isn't jazz, or Bebop isn't jazz, only Dixieland is authentic jazz, and so forth. The history of jazz is replete with these kinds of conversations and positions.

Why the definition of jazz could be subjective

What if it were true that jazz has no essential features that all jazz performances exemplify. Perhaps the concept of jazz is an open concept with only family resemblances between member-types that fall under the concept without there being any essential or central features that all and only games or jazz contain. Such a conception is what Wittgenstein was discussing with his language games.

If there are no central or essential features that every jazz performance exhibits or exemplifies, then such a failure to have an independent ontological status opens the door to arbitrary or idiosyncratic and subjective opinions about what constitutes jazz and which sub-genres to include or exclude. Since the concept would be open-ended, the reference can be fluid and change over time with different genres and performances qualifying and disqualifying as jazz depending upon which subjectively arbitrary conception of jazz was used.

Why jazz cannot be defined as black music

At the Oxford Bibliographies website, "Introduction to Jazz," they make these remarks:

“Defining jazz has been central to delineating the disciplinary purview of jazz scholarship, but this has never been easy. As a body of more or less “popular” music disseminated in recorded form, the music has undergone rapid development over the course of its history, and each transformation in style has prompted debate among jazz musicians, critics, and fans as to whether or not the new style was in fact jazz. Such debates have often revolved around the role of improvisation and its relative emphasis in any given style, the degree to which each new form of the music could be understood to “swing”—i.e., to exhibit a valued rhythmic quality thought to be essential to good jazz—and the extent to which each new style manifested certain core African or African American musical concepts and principles. The latter consideration has prompted many scholars to eschew parochial considerations of style altogether and situate jazz not as a distinctive form of music in its own right but as one expression among many within the very broad category of "black music".”

But this last suggestion is exceedingly useless and unhelpful. There is no such thing as "black music." Even if there were, it would need to include music that wasn't jazz like the Blues. Any legitimate use of the term "black music" would undoubtedly include the blues genre, and blues by itself, is not jazz, period.

So, we cannot ignore jazz's musical features (this includes "style" mentioned above). We need to know "what form of music" it is contrary to the above contrary suggestions. Otherwise, blues and jazz would be the same type since each is black music. Since blues and jazz are not the same kinds of music, this is a reductio ad absurdum argument against the above suggestions.

The reductio is this:

Either jazz is best defined as black music or not. Assume black music is the definition of jazz.

- 1. Blues music is not jazz (ask anyone), but

- 2. Blues is American "black music" because it, like jazz, was predominantly initially developed by people of color, especially Afro-Americans.

- 3. If black music characterized jazz, then jazz would be the same type of music as the blues (both are black music in the sense specified).

- 4. Therefore, jazz cannot be merely black music.

We were led to a contradiction (jazz is and is not the blues). Therefore, the assumption that jazz can be defined as "black music" is a false one since it leads to a contradiction.

CONCLUSION: Therefore, jazz is not best defined, characterized, or conceptualized as equivalent to black music.

➢ To what shall we turn to next to determine a definition for jazz?

After denying that jazz can be uncontentiously defined by saying, “This is an extremely complicated and contentious debate, and it is not this book's intent to solve these issues,” Benjamin Bierman addresses the question "What are the elements of jazz?" by remarking that “discussing the essential elements of jazz is the best way to become acquainted with this exciting genre of music initially.”[9]

Suppose there exist "essential elements of jazz," then contrary to what Bierman claims to believe about the impossibility of defining jazz, these same essential elements could be used to define jazz.

Robert Kraut on Problems With Defining Jazz

Robert Kraut raises concerns for the enterprise of defining jazz in his "Why Does Jazz Matter To Aesthetic Theory?." He seems mildly sympathetic and in favor of pinning jazz down musically, as well as supporting the search by theorists for capturing and explaining jazz.

Ignoring disputes about controversial cases, Kraut suggests we look at uncontroversial central paradigms of jazz performances as legitimate data for theorizing about jazz.

“It is difficult to specify what qualifies as pure jazz; nor is such specification necessary. Like other art forms and genres, jazz offers various central paradigms about which there is little if any controversy (but even Miles, in later stages, was occasionally said to have abandoned jazz; and Coltrane, when playing with Rashid Ali and Pharoah Saunders, was sometimes said to have evolved out of jazz and into some other form). Clearly, various standards of similarity and difference are deployed when determining whether a musical event lies sufficiently close to paradigm cases to qualify as jazz. Often there is room for dispute; such disputes about style and genre categorizations are familiar (and perhaps essential) throughout the artworld.”[10] (bold not in original)

Kraut supplies two lines of thought for philosopher's interest in the philosophy of jazz—one about theory, the other about the need for data collection.

- THEORY LINE OF THOUGHT: Any genuine theory must be about data.

Aesthetic theory must be about aesthetic objects. Art works are aesthetic objects. Jazz is an art work form. Therefore, aesthetic theory qua aesthetics must be concerned with jazz.

- DATA LINE OF THOUGHT: All genuine theories are about data. Since aesthetic theories must concern themselves with jazz, they must pin down what jazz is, what it consists of, and what it is like musically?

He explains that because any "genuine aesthetic theory" must be theorizing about (empirical?) data, well-played jazz is an art form, and aesthetic theories theorize about art forms, it follows that "Jazz performances are part of the data, and thus part of the tribunal by which aesthetic theories must be tested and evaluated."[11]

CONCLUSIONS: Aesthetic Theory strives to be a genuine theory. All theories must be about (empirical?) data. Jazz is under the purview of aesthetic theory since it is an art form. Therefore, aesthetic theory must know what jazz is. A way to examine jazz is to investigate past jazz performances and use them as data for theorizing. Therefore, philosophy must study jazz, including actual past performances from recordings, as well as current live performances.

So aesthetic theories about jazz need to examine the data of jazz.

➢ But which data?

What is the Data of Jazz?

Of the several possible candidates for relevant data to mine for in jazz, none seems more central than the actual music that jazz musicians have already played. There is sufficient data that books are published containing three hundred jazz standards.

Although, contrary to the previous line of thought, rather than mine data primarily from past recordings, one could study current practicing jazz musicians.

Let's not over-think this right here and ask instead, if there is anything that the vast majority have in common during the playing of the three hundred songs chosen as representatives of unquestionably paradigmatic jazz. There will be many things in common, but none by itself can uniquely individuate (or distinguish between) jazz as a musical genre from other musical genres since non-jazz music that also uses many of the the same musical features: swing is done by rockabilly, blues can have all of HSI: hybridization of two scales (diatonic and pentatonic), syncopation, and improvisation, improvisation occurs in country music to Indian ragas. Regardless, what do the incontrovertible jazz songs share as musical features in common?

Musical features in common amongst incontrovertibly jazz tunes

- Hybridization is synthesizing the two musical scales of a European diatonic (seven note) system with an African inspired pentatonic (five note) (blues) system.

- Syncopation emphasizes weak beats or off the beat. See Onttech6. What is syncopation?

- Improvisation is done in many genres besides jazz, including Indian ragas, the blues, rock, and even classical (Bach & Mozart were stupendous improvisers). See Ontimpr1. What is improvisation?

What are paradigm examples of past jazz performances? What do all past jazz performances have in common?

Answer: very little in common if required by every possibly qualified jazz performance. But it need not be all or nothing.

We can use fuzzy logic and degrees of inclusion, so the question as jazz data now becomes: What do the vast majority of agreed paradigm performances of jazz have in common?

Here the answer is HSI (Hybridization, Syncopation, and Improvisation).

Which Jazz Performances Should Philosophy of Jazz Study?

An immediate recommendation that would limit controversy is to include only past performances that all parties agree were jazz performances. Everyone would agree that Miles Davis playing "On Green Dolphin Street" was a jazz performance, but might balk at some song from Miles's later catalog as an appropriate example.

Fine, for the moment, we exclude that song from what everyone agrees should be included in the jazz canon used for analysis. Call this resulting musical grouping of past jazz performances the 'indisputable jazz canon'. Anything contentious has been excluded. However, if any of the evaluators were to argue that the jazz canon is exceedingly small, say in the history of jazz there have only been three real jazz songs performed, then that theorist and such a theory would be laughed out of the room.

What is the maximum number of jazz performances given on Earth?

➢ What is the maximum number of jazz performances there could have been on planet Earth since the beginning of jazz in 1890?

It turns out these estimates are difficult to determine for numerous reasons.

Estimates for the entire planet are guesstimated at the end. As a beginning, the investigation restricts itself to professional jazz musicians in the United States. In 2003, the National Endowment for the Arts NEA 🎭 (United States) published their report #43, Changing the Beat: A Study of the Worklife of Jazz Musicians  by Joan Jeffri using data compiled from four major U.S. cities: New York, San Francisco, New Orleans, and Detroit.[12]

The dedicated investigators report in "Survey Background," that:

by Joan Jeffri using data compiled from four major U.S. cities: New York, San Francisco, New Orleans, and Detroit.[12]

The dedicated investigators report in "Survey Background," that:

“In an occupational sense, jazz musicians are difficult to identify. While national-based surveys such as the Current Population Survey, conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, are used to estimate the labor force by occupation, the occupation categories are not detailed enough to distinguish jazz musicians from the larger classification of Arts, Design, Entertainment, and Media Occupations, or even from the more specific category of Musicians and Composers. In addition, the national-based surveys do not cover detailed questions/subjects germane to the study of jazz musicians.”[13] (bold not in original)

The following estimates of jazz musicians were generated: 1,723 in the New Orleans area; 33,003 in New York; and 18,733 in San Francisco.

After standardizing the three locations for population, San Francisco had the largest concentration, 2.8 jazz musicians for every 1,000 people in the area. This number was 1.5 times higher than the concentration in New York, which was 1.8 jazz musicians per 1,000 people, and more than twice the concen-tration reported in New Orleans. The chart above summarizes these results.

For more information, see "Finding the Beat: Using Respondent-Driven Sampling to Study Jazz Musicians," by Douglas D. Heckathorn and Joan Jeffri. Published in Poetics, Vol. 28, No. 4. February 2001.

➢ Given these limitations and limiting the chosen universe's domain only to registered professional jazz players in the United States, how many jazz performances occurred over 127 years (1890 - 2017)?

At the start of jazz, there would annually be a smaller total number of performances than in later years of jazz history. First, calculate the maximum. Assume 7.42 billion people, but much less in the past hundred years, so average over 127 years is 4 billion. The percent of jazz musicians amongst this population performing ten songs that day is .00001% of the population. Number of days in year 365 x 127 years = 46,355. On any one day in the United States, how many jazz songs do jazz musicians play?

One estimate had between 50,000 and 300,000 musicians in the US. What percentage of these are jazz musicians? It is unclear.

A reasonable estimate is 100,000 to a maximum of 200,00 professional jazz musicians currently in the United States in 2017.

What is the average number of jazz musicians over the past 127 years in the United States? If there are currently 100,000 jazz musicians, then in the past, there were fewer. For purposes of calculation, make the average over 127 years be 35,000 per average year. On an average day, how many of these musicians are working or practicing? If we include practicing, then many jazz musicians are either gigging or practicing on any given day. Assume that half of the total on any given day over 127 years play at least ten songs. Half of 35,000 is 17,500. Over such a large period of time, individual musicians over their entire lives don't play when very young or very old. Because of this, cut our total into half once again. Half of 17,500 is 8,750. 8,750 x 46,355 equals 405,606,250. That times ten songs makes it 4,056,062,500.

CONCLUSION: This are four billion jazz song performances played in the United States over 127 years on the Earth.

If someone had told you over the course of jazz's history from 1890 until today there have been a billion jazz performances you might have reacted by finding this a reasonable number. A reasonable estimate then is one to ten billion jazz song performances over the history of jazz over the entire planet.

- More than 33,003 musicians only in New York 2001.

- 18,733 jazz musicians in San Francisco in 2001.

- 1,723 musicians in New Orleans in 2001.[14]

Difficulties With Determining the Number of Jazz Musicians in the United States

Ignoring the problem of who judges who qualifies as a jazz musician, one could use self categorization to start with. Let the musicians label themselves and go from there.

It is exceedingly hard to estimate the number of musicians in the United States as explained at Artist Revenue Streams "How Many Musicians Are There (In the United States)?." They cite three major factors making the problem challenging:

There are three particular challenges in estimating the size of the musician population in the United States:

- 1. There is no agreed-upon definition for “musician”, nor certifications or qualifying tests.

- 2. There is no one organization that represents all musicians.

- 3. The government’s statistics excludes a huge chunk of the musician population by their own accounting standards.[15]

First, who exactly is included in the category of musician: "what do we mean when we use the word “musician”? Are we just talking about performers and recording artists, or does the definition also include composers and songwriters? How about music teachers?"[16]

Second, what is the system for determining musician inclusion, "those who are making a living from music. The question is, should it be based on work week hours, career lifespan, music degrees, a certain number of recording or composing credits, education, income, label affiliation, union membership, or a combination of these things? Or, organizational affiliations, or governmental census data, or private data from Nielsen SoundScan and Nielsen BDS, or Pollstar, etc."[17]

According to TheJazzLine in 2014 jazz sales have decreased to 2% of sales of jazz albums in any of four formats totaling just over 5 million units (albums):

"In 2011, a total of 11 million jazz albums (CD, cassette, vinyl, & digital) were sold, according to BusinessWeek. This represents 2.8% of all music sold in that year. However, just a year later, in 2012, that percentage fell to 2.2%. It rose slightly to 2.3% in 2013 before falling once again to just 2% in 2014." "That 2% represents just 5.2 million albums sold by all jazz artists in 2014. In comparison, the best-selling artist of 2014, Taylor Swift, sold 3.7 million copies of her latest album ‘1989’ in the last 2 months of 2014 alone.""

Problems with Definitions

In the past ten years several philosophers including Jonathan McKeon-Green and his co-author Justine Kingsbury have raised serious concerns about the possibility of defining something disjunctively and they have sometimes made these claims in relationship to defining jazz in particular.

One of the issues raised by McKeown-Green and Kingsbury regards specific methodological concerns regarding when particular approaches to defining something are appropriate or inappropriate. When should one base a definition exclusively on intuitions and classificatory practices? McKeown-Green argues that this sort of approach and methodology can only be successful if the thing being defined is determined by human conceptions of whatever it is.

“Exclusive appeals to intuitions and classificatory practices only work if the nature of the thing being defined is determined by our conception of it, that is, by the way we construe it--the features we take it to have in virtue of being the thing it is.”[18] (italics in original)

How is this relevant for defining jazz?

If jazz is not determined by our conception of it ("by the way we construe it"), then the methodology for defining jazz based on intuitions and classificatory practices cannot be successful, or so McKeown-Green and Kingsbury appear prepared to argue.

Two questions then have been raised that should be addressed to make argumentative progress on the possibilities for defining jazz.

- Question (1): Is jazz determined by human conceptions so that use of intuitions and past classificatory practices are relevant for defining jazz?

- Question (2): If jazz is not determined by human conceptions, then what, if anything, does determine its nature?

Reasons why jazz is determined by human conceptions

When asking the question what is jazz where should one turn to for answers? One approach would be to ask people what they believe constitutes jazz as a musical genre. Someone might argue that this is a reasonable thing to do because humans are the causal origin explaining why jazz exists in the first place. Jazz came into existence as the result or as a consequence of humans playing music in a particular way. Because humans invented jazz, it is only natural to ask the creators what it is that they think amounts to the thing that they created. There is no one better to query on what is this type of thing than the very people responsible for its existence and then find out what people believe are the features used to carve out this particular musical type.

➢ Is this a good way to proceed?

Reasons why jazz is not determined by human conceptions

What, if anything, can be determined exclusively by human conceptions?

Isn't everything determined by human conceptions? Aren't all concepts manufactured by humans so that it is humans that determine the boundary conditions for what word or sound is associated with a particular conception and these conceptions because they can be arbitrarily combined are therefore determined by their makers, which are humans.

First, it is false that only humans can make and use concepts. To the extent that concepts are a consequence of mind's activities (of classification and categorization used during activities) other entities besides humans have minds that may result in conception creations. What other mind's besides humans could possibly produce concepts will include other animals, such as great apes 🦍 🦧, chimpanzees, dolphins 🐬, pigs 🐷, dogs 🐶, cats 🐈, and birds 🐦 🦢 🦅. Other possible mind's would include any intelligent aliens 👽, such as ancient self-conscious Martian persons. Were angels 👼 to exist, they could have and produce concepts, as well as all other mythical type creatures such as trolls, demons, and leprechauns, to name a few.

CONCLUSION: Therefore, it is false that everything is determined by human conceptions since non-humans also use and determine some concepts.

Second, can something exist and be understood by humans to exist that has not been determined by human conceptions? The simple answer is "Yes," some things exist with their own identity conditions that were not determined by human conceptions. Take, for example, the phenomena studied in quantum mechanics. The theory of wave-particle duality was forced onto theorists as a consequence of results from scientific experiments. If the experiments had not produced such surprising and counter-intuitive results, as in the two slit experiments, then no human would have bothered to produce such weird and unintuitive concepts for theorizing about the quantum world. Reality forced theorists to move past their earlier conceptions to novel ones required to account for the quantum phenomena under investigation.

What determines jazz if human conceptions do not?

The question of jazz's nature assumes it has a nature. First we should get clear on what it means to have a nature.

What is a nature?

The word "nature" has so many meanings and is used in several non-equivalent contexts. In the usual sense meant by philosophers nature is the same as the essence of something, or essential properties. Essential properties often get spelled out in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions.

Now hyperlink to the sections of PoJ.fm that deal with these factors.

NOTES

- ↑ Thomas Brothers, Louis Armstrong, Master of Modernism (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2014), 269, as quoted in Aleksey Nikolsky, "Possession is Nine Tenths of the Law: The Story of Jazz and Intellectual Property," 2, footnote 1.

- ↑ Scott Deveaux, "Constructing the Jazz Tradition: Jazz Historiography,” Black American Literature Forum 25, no. 3 (Autumn 1991), 528-529.

- ↑ Thomas E. Larson, History & Tradition of Jazz (Iowa: Kendall Hunt Publishing Co., 2002), 2.

- ↑ James O. Young and Carl Matheson, "The Metaphysics of Jazz," The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 58:2, (Spring 2000): 125.

- ↑ Benjamin Bierman is Associate Professor in the Department of Art and Music at John Jay College, City University of New York. His text published in 2016 is “a listening and performance-oriented introduction to the history of jazz,” according to the description on the back cover of Benjamin Bierman's Listening To Jazz, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016). See a book review by Ed Berger at Journal of Jazz Studies, vol. 12, no. 1, (2019), 92-98 with comments by Bierman on the 2nd edition that Berger had not seen.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Benjamin Bierman, Listening To Jazz, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 4.

- ↑ James O. Young and Carl Matheson, "The Metaphysics of Jazz," The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 58:2, (Spring 2000): 125. (bold italics not in original)

- ↑ Changing the Beat NEA Report #43 has 84 percent male jazz musicians of those studied in 2001. See Findings box on p. 2.

- ↑ Benjamin Bierman, Listening to Jazz, 2nd ed., (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019).

- ↑ Robert Kraut, "Why Does Jazz Matter To Aesthetic Theory?," Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 63:1 (Winter, 2005), 4.

- ↑ Robert Kraut, "Why Does Jazz Matter To Aesthetic Theory?," Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 63:1 (Winter, 2005), 3.

- ↑ Joan Jeffri, Changing the Beat: A Study of the Worklife of Jazz Musicians, Volume I: Executive Summary, National Endowment for the Arts, San Francisco Study Center and the Research Center for Arts and Culture, NYC, January 2003. National Endowment for the Arts Research Report #43.

- ↑ Joan Jeffri, Changing the Beat: A Study of the Worklife of Jazz Musicians, Volume I: Executive Summary, National Endowment for the Arts, San Francisco Study Center and the Research Center for Arts and Culture, NYC, January 2003, 6. National Endowment for the Arts Research Report #43.

- ↑ Joan Jeffri, "Changing the Beat: A Study of the Worklife of Jazz Musicians," Volume One: Executive Summary, NEA Research Division Report #43, 2002, 6.

- ↑ How Many Musicians are There in the United States?

- ↑ How Many Musicians are There in the United States? quoted from under section "Who gets included?"

- ↑ How Many Musicians are There in the United States? quoted from under section "Musician criteria."

- ↑ Jonathan McKeown-Green, "What is Music? Is There a Definitive Answer?," The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 72:4 (Fall 2014), 393.