Difference between revisions of "Ontmusic27. Slow Music"

(→PoJ.fm's Impossible Symphony 2017 #1) |

(No difference)

|

Latest revision as of 14:04, 10 April 2022

Contents

Slow Music[edit]

How slowly can music be performed? Is there a limit?

There are some well known pieces of music that are played very slowly. Here is a list at "What's the slowest classical music ever?.

Of course, one needs to clarify what one has in mind by slow. There are at least three different possible characterizations of slow music.

- One can have a lot of time in between the playing of the notes, or between musical sections, which we can call intervallic slowness.

- The piece of music is slow to evolve, it doesn't change (any or much) over an extended period of time, which can be called progression slowness.

- A musical work could take a very long time for it to be played to completion, which can be labeled completion slowness.

See the Table of Slowness Properties below with these three types of slowness properties applied to musical works.

St. Burchardi Church in Halberstadt, Germany

St. Burchardi Church in Halberstadt, Germany

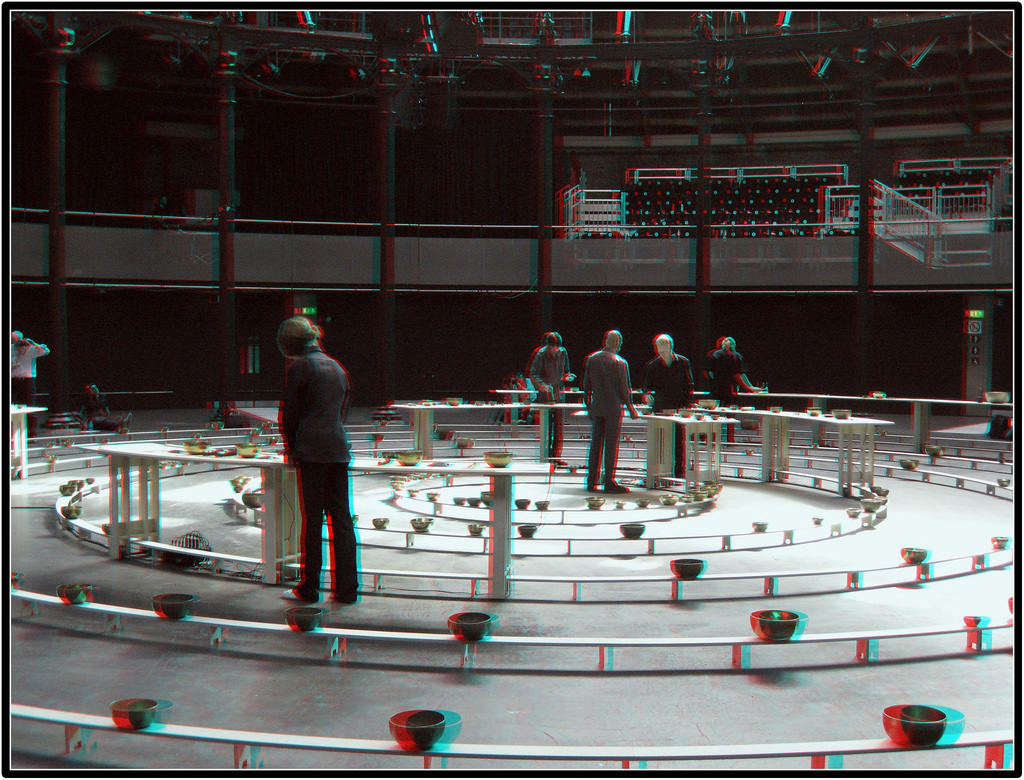

John Cage's Organ²/ASLSP (As SLow aS Possible), a 1987 organ piece is currently being played at St. Burchardi church (shown above) in a performance scheduled to last 639 years (started September 5, 2001 and scheduled to complete in 2640 A. D.).

Cage's Organ2 (pictured above) has a mechanical air bellows continually pumping into the organ pipes and weighted bags holding down the appropriate key(s) on the organ to play notes. To date, the tones have changed only 12 times over the last fifteen years.

However, this lack of change of tone makes Cage's piece quite tedious to listen to and too unchanging auditorily to be of only limited interest, musically speaking. As a model, consider a child who plays the same continuous tone with a pennywhistle and then plays it over and over, one will quickly tire of hearing such a non-changing and continuous tone. Something similar fairly quickly happens after listening to Cage's Organ2.

Cage's piece, however, does not hold the record for the length of performance even were it to succeed at 639 years. That honor is (potentially) currently held by Longplayer (pictured above). This song was composed/constructed by Jem Finer, of the Pogues, and has already been playing continuously for the last seventeen years (in 2017) and the piece does not conclude until December 31, 2999 after a millennium (1,000 years) never repeating the exact same musical pattern until after completion.

On the other hand, Jem Finer's piece has six different pieces of music that a computer manipulates and plays together. Here there are changes in sounds and rhythms and the music remains contemplative and not annoying; rather, it promotes reflection and a sense of peace and harmony. The music is never exactly the same over any two minute period for one thousand years.

Table of Slowness Properties for Slow Music[edit]

| Composer | Composition | First Played Start Date | Proposed End | Intended Length | Intervallic Slowness | Progression Slowness | Completion Slowness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erwin Schullhoff | In futurum | 1924 | don't know | ? | Yes & No | Yes | Yes or No |

| Yves Klein | Monotone-Silence Symphony | 1960 | 49-51 minutes after start | 5'-7' of a D-chord followed by 44 minutes of rests | Yes | Yes | No |

| John Cage | 4'33" | 1957 | 4'33" after start | potential indefinite length | Yes & No | Yes | Yes or No |

| Jem Finer | Longplayer | 2000 | 2999 | 1,000 years | No | No | Yes |

| John Cage | Organ²/ASLSP (As SLow aS Possible) | 2002 | 2624 | 639 years | No | Yes | Yes |

| Andrew Kania | Composition 2009 #3 (see below) | 2009 | ? | indefinite | Yes & No | Yes | Usually No |

| PoJ.fm | PoJ.fm's Impossible Symphony 2017 #1 (see below) | 2017 | Never in our universe | Less than denumerably infinite | Yes | Yes | Yes |

“In most fields of philosophy, one must be content with hypothetical examples, but philosophers of the arts have the distinct advantage of being able to produce actual examples to illustrate their theories (or refute others).”

Andrew Kania in "Silent Music," p. 21

- Reasons for Yes: A musical performancemance has intervallic slowness if there are long pauses between musical notes or sections. In "In futurum" and during a performance of "Cage's 4'33" there are long pauses between musical sections, where a pause is determined by not having the performer produce musical sounds. In 4'33" the first 'movement' as performed by David Tudor on the piano was 30" and Tudor succeeded during this time period in not making any musical sounds. After this first movement, there is a second long pause where the performer also does not make musical sounds for 2'23" so this is an extended pause in sound production as well. The third and final movement of 1'40" can also be considered a long pause between musical note making. Andrew Kania's Composition 2009 #3 can have intervallic slowness because the piece can be very long so that there are, in effect, a lot of rests in the score, and these count as long pauses if the length of time chosen for the performance by the performer are themselves long.

- Reasons for No: During the performance of any silent musical work no musical sounds should be produced therefore there are no pauses between musical notes since there are no musical notes between which to have pauses. Hence, a silent piece of music has no intervallic slowness. This is certainly true of Kania's entirely silent composition because having no sounds or notes there is nothing to be intervallic about. There are no intervals in between anything; only a beginning and an end, but the entire musical work is unitary without interruption so no intervals are available for analysis.

- Additionally, in the case of David Tudor's actual first performance of 4'33" there were not long pauses between musical sections because Tudor fairly quickly raised and then relowered his piano keyboard lid to mark the end and indicate the beginning of each movement. Therefore, there was no intervallic slowness between these sections because Tudor's movements with the piano lid were not slow.

- Reasons for Yes or No: for completion slowness are dependent upon the length of time chosen by the performers. Cage leaves open the total time of his piece 4'33" so it can conceivably be played shorter or longer than this amount of time thereby changing whether a performance takes a short or long time to complete. Schulhoff's "In futurum" also can have a variable length of time within which it can be performed, according to the composer's instructions.

PoJ.fm's Impossible Symphony 2017 #1[edit]

Philosopher Andrew Kania  has composed a silent piece of music, Composition 2009 #3, with the musical score consisting of this set of instructions:

has composed a silent piece of music, Composition 2009 #3, with the musical score consisting of this set of instructions:

The score reads as follows: “Indicate a length of silence, using the usual cues with which you would signal the beginning and end of a single movement, song, etc. (The content of this work is the silence you frame, not any ambient noise.)”[1]

Kania claims that on both his and Jerrold Levinson's definition of a musical work that Kania's "Composition 2009 #3" qualifies as one.

PoJ.fm tries its hand at composition paralleling Kania's Composition 2009 #3 as follows:

- The score for the PoJ.fm Impossible Symphony 2017 #1 reads: “Have each member of the symphony orchestra on their own instrument simultaneously play the same note for around one second (say middle C key of a piano), wait longer than the history of the entire universe you find yourself within, after this have an orchestra play the same note for approximately the same length of time as the first time. This completes the piece.”

- Impossible Symphony 2017 #1 seems to have musical score instructions comparable to Kania's Composition 2009 #3.

- One might quibble with the time scale directive ("wait longer than the history of the entire universe you are in") as being impossible to achieve. Of course, the symphony may not be called the "Impossible Symphony" for nothing. Still, an interdimensional traveler to alternate universes could switch from our universe with a possible heat death expansion of 40 or 50 billion years to a different universe that has a longer life than 50 billion years. Since this seems conceptually possible, the musical score instructions are not incoherent or logically impossible because they are not self-contradictory. The instructions are not self contradictory if universes can die or cease any functioning and different universes are possible with different life spans or times from creation to cessation of that universe.

We know that according to some cosmological theories of universe's possible histories that have the universe starting at a singularity, exploding outward and expanding, but eventually the gravitational attraction of all matter to each other slows the expansion to a halt and then proceeds to contract back to a singularity known as the "Big Crunch."

“Expanding universes need not continue to expand forever. They do so if their average density is below a critical value. But if their average density exceeds this value then at some time in the future the expansion will be reversed into contraction. Redshifted radiation from distant sources will become blueshifted and the universe will collapse toward a ``Big Crunch" of ever-increasing density and temperature.”[2]

If these theories were actually exemplified by different possible universes with either different amounts of matter, or different amounts of forces exploding the universe outward from the initial singularity, then different universes could exist with different total lengths of time of their respective historical lengths from birth of a universe at its Big Bang to its death at the end of the Big Crunch. This makes the instructions in the Impossible Symphonies of "wait longer than the entire history of your initial universe" to be possibly followed in some sense because different total universal histories are possible. Then, it is only a matter of being able to switch from a shorter timeline universe to a longer timeline universe to fulfil the Impossible Symphonies musical score instructions.

Why Impossible Symphony 2017 #1 is the Denumerably Slowest Music in All Three Categories of Slowness[edit]

Assuming for the moment that Impossible Symphony 2017 #1 is the score for a musical work, it can be argued to be one of the slowest denumerably possible musical works in all three categories of slowness.

- Intervallic slowness is apparent in the time between the first Middle C note and the last one is longer than the history of the performer's universe, which could be multiple billions of years. That's slow to develop with a large interval of silence between the opening and closing notes.

- Progression slowness occurs since the piece proceeds over billions of years in the middle with unvarying rests.

- Completion slowness results from the longer than the history of your universe requirement, making this piece take billions and billions of years to perform.

Why Impossible Symphony 2017 #2 Could Be Slower Than Impossible Symphony 2017 #1 [edit]

Because the time frame is indeterminate of different universes since they can have different lengths and histories there can BE different histories some longer and shorter than others as was argued above

If one finds oneself initially in a shorter total history universe, say a twenty billion year universe, and could travel from this to a thirty billion year universe then one could perform Impossible Symphony #1. Another person who finds themselves initially in the thirty billion year universe must travel to a longer timed universe that could be a forty billion years universe. This second Impossible Symphony (#2) performance could then be longer than Impossible Symphony #1.

Because the impossible symphony can be carried out in different possible time frames, Impossible Symphony number #2 can, in principle, take longer to complete than was Impossible Symphony #1.

Problems for Pieces With Large Intervallic Slowness[edit]

CLAIM: At best, pieces with large intervallic slowness are either really bad music or not music at all.

By definition of large intervallic distances there could be a long period of no sound production between musical notes. The following are facts about this type of situation and audience members likely reactions to such a piece. Let's use a shorter version of the Impossible Symphony by having the period of time between the playing of the two middle C's on a piano only be an hour in between. Call this the Possible 1 Hour Symphony #1.

- Audience members would get bored sitting around waiting for an hour while nothing is happening between the playing of the two C's.

- If not warned beforehand, most audience members would be confused and think only one note has been played. After some time, they could easily believe the performance is over.

- In an hour's time of limited activity by performer(s) probably quite a bit of other noises would likely intervene by accident disrupting audience's members perceptions of experiencing a musical work as a whole. See below on gestalt problems at number 6.

- Because of the large interval of no intended sound production by musician(s) the piece virtually has no rhythm. Rhythmless music can be boring because humans relate well to many types of rhythms.

- Generally speaking, when large stretches of silence during intervallic slowness occur there is no beat. Music without a beat is boring or non-existent.

- With virtually no activity taking place during these intervals the audience fails to have a gestalt phenomenological auditory experience. The sounds don't seem to be coordinating together as some sort of whole. Instead, all that audience members perceive is the hearing of middle C on a piano and only one hour later another C. The two C's won't be perceived as belonging together. It will be merely episodic perception of first this event and later another. Nothing will appear inevitably drawing to a denouement as can happen during the listening of a musical composition.

- Surely the simplicity of structure of the Possible 1 Hour Symphony also leaves it at best as bad music, or as has been argued above, possibly not music at all.

NOTES[edit]

- ↑ Andrew Kania, "Silent Music," The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism Vol. 68, No. 4 (FALL 2010), 351.

- ↑ John D. Barrow, "Cosmology, Theories," in Astronomy and Astrophysics Encyclopedia, ed. Stephen P. Maran.