Ae1. Are jazz improvisations inherently inferior to non-improvised compositions?

Contents

Discussion[edit]

Introduction[edit]

Some theorists, such as Ted Gioia, has suggested that improvisations because of their immediacy of composition may be inherently inferior to non-improvised compositions that permit the composer to reflect upon the musical content and improve it as one composes. A non-improvised composer can change his or her or their mind and rewrite and reconfigure such a composition. The ability to recompose before final work product completion makes non-improvised compositions inherently superior to spontaneously composed ones for this reason.

Reasons why non-improvised compositions can be superior to spontaneous improvisations[edit]

Because a non-improvising composer can take time and evaluate the qualities of an actively developing composition permits this composer to improve the composition. One can in effect test out what may be a possible improvement by altering previously established sections. Here we might call this advantage of leisurely composing the improvement aspect.

Another aspect of leisurely composing is a structural complexity overview. A leisurely composer can 'see the big picture' since the overall form of this in-production composition can be reviewed by the composer. He or she or they can recognize problems or difficulties with the shape of the entire production and move sections around that affect the musical impact. Perhaps repeating this section here with an addition of a new voicing or new instrument may improve the sonic result. Spontaneously improvising musicians have a harder time with any overall structural changes since no earlier played improvisations can alter anything. Furthermore, since an improviser has not yet completed the improvisation until it is finished it cannot be known what the entirely completed musical form looks like. This places the spontaneous improviser at a disadvantage to the leisurely composer who can perceive the entire form and shape of a composition permitting possible changes before the composition ever gets performed. Composing improvisers must compose on the fly and so cannot have any opportunity to discard or revise or improve any previously performed sections. Any 'problems' found during an improvisation one is stuck with accepting since it is already too late to change since the performance has already occurred.

Reasons spontaneous improvisations need not be inferior to leisurely compositions[edit]

There are several reasons why a spontaneous improvisation could be superior to a non-improvised composition. First, not all non-improvised compositions are of the same quality. Both non-improvised compositions and improvisations come in various degrees of good and bad. There can easily be very bad compositions that may have taken a lot of time to compose. Because both non-improvised compositions and improvisations can exist on a scale from really really bad to great, were we to compare a very bad non-improvised compositions to a great improvisation it is obvious which one is better musically under any description.

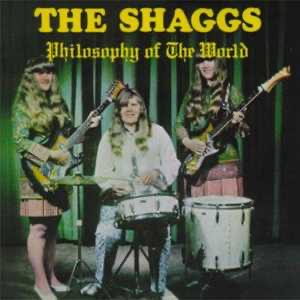

For example, if we compare a great improvisation of Sonny Rollins (b. 1930), such as "Blue 7," to a composition badly played like "Philosophy of the World" by The Shaggs,  then everyone agrees that Rollins's performance and song is superior in every way: melodically, rhythmically, tonally, and orchestrally with better harmony.

then everyone agrees that Rollins's performance and song is superior in every way: melodically, rhythmically, tonally, and orchestrally with better harmony.

To establish this, see what critics have said in analysis of these two pieces.

Debra Rae Cohen in her Rolling Stone positive review of the 1980 reissue of "Philosophy of the World" gives a spot-on characterization of what it is like listening to their performance.

“Like a lobotomized Trapp Family Singers, the Shaggs warble earnest greeting-card lyrics [see lyrics below] ( . . . ) in happy, hapless quasi-unison along ostensible lines of melody while strumming their tinny guitars like someone worrying a zipper. The drummer pounds gamely to the call of a different muse, as if she had to guess which song they were playing—and missed every time.”[1] (bold not in original)

The AllMusic Review by Cub Koda appreciates the charm of charmlessness in The Shaggs performances.

“The guilelessness that permeates these performances is simply amazing, making a virtue out of artlessness. There's an innocence to these songs and their performances that's both charming and unsettling. Hacked-at drumbeats, whacked-around chords, songs that seem to have little or no meter to them ("My Pal Foot Foot," "Who Are Parents," "That Little Sports Car," "I'm So Happy When You're Near" are must-hears) being played on out-of-tune, pawn-shop-quality guitars all converge, creating dissonance and beauty, chaos and tranquility, causing any listener coming to this music to rearrange any pre-existing notions about the relationships between talent, originality, and ability.[2] (bold not in original)

Here are the lyrics to "Philosophy of the World."

When we turn to a consideration of the musical merits of the spontaneous improvisation during Rollins's "Blue 7" all are in agreement about its musical virtues.

“The performance is among Rollins' most acclaimed, and is the subject of an article by Gunther Schuller entitled "Sonny Rollins and the Challenge of Thematic Improvisation". Schuller praises Rollins on "Blue 7" for the use of motivic development exploring and developing melodic themes throughout his three solos, so that the piece is unified, rather than being composed of unrelated ideas. Rollins also improvises using ideas and variations from the melody, which is based on the tritone interval, and strongly suggests bitonality (the melody by itself is harmonically ambiguous, simultaneously suggesting the keys of Bb and E).”[3] (bold not in original)

“"Blue 7" from ‘Saxophone Colossus’ is a masterpiece, hence it is the kind of performance that one hears anew with each listening and that is difficult to discuss and describe. Its heritage, as Gunther Schuller pointed out in his detailed analysis, includes Monk’s "Misterioso" and the Miles Davis-Sonny Rollins "Vierd Blues." It begins with an almost nonchalant and tranquil bass line by Doug Watkins. Upon this, Rollins states the theme, a simple blues line that has a strong individual character. Yet it is also suspended in an ambiguous bitonality. The piano’s entrance behind Rollins assigns it a specific key, and Rollins begins to explore its implied brilliance expertly. The performance builds from one phrase to the next, yet that structure is so logical and so comprehensive, with its details so subtly in place, that it is as if Rollins had not made it up as he went along, but had conceived it whole from the beginning. . . . ”

“Almost everything that Rollins plays on "Blue 7" is based on his opening theme, but Rollins also structures and builds—he even builds on his elaborations and his brief interpolations, and he is not afraid of an almost direct recapitulation of his theme at one point during the performance. The order and logic of the performance extends also to Roach’s solo, based almost entirely on a triplet figure and a roll, while Tommy Flanagan’s non-thematic piano solo serves as a kind of effectively contrasting, lyric interlude. "Blue 7" is one of those rare performances which almost anyone can appreciate immediately, I think—anyone, from the novice who wants to know where the melody is, to the sympathetic classicist who can appreciate how highly developed the jazzman’s art has become.”[4] (bold and bold italic not in original)

CONCLUSION: Some spontaneous improvisations can be musically superior to some non-improvised compositions. Therefore, not all improvisations are inherently inferior to all compositions.

NOTES[edit]

- ↑ Debra Rae Cohen, "Philosophy of the World," "Reception."

- ↑ Cub Koda, "AllMusic Review by Cub Koda of the album 'Philosophy of the World'"

- ↑ "Sonny Rollins's 'Saxophone Collosus'," last.fm.

- ↑ Martin Williams, "Martin Williams on Sonny Rollins: Spontaneous Orchestration," The Jazz Tradition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983), 188–89.