DescartesOnMaterialFalsity

Contents

- 1 Introduction to Descartes's Philosophy

- 2 Introduction to Descartes's Theory of Ideas

- 3 Descartes's definitions of thoughts and ideas

- 4 Important questions in Descartes's theories of ideas

- 4.1 Epistemological questions in DTOI

- 4.2 Mind questions in DTOI

- 4.3 Representation questions in DTOI

- 4.4 Objective reality questions in DTOI

- 4.5 Questions about the Passions in DTOI

- 4.6 Material falsity questions in DTOI

- 4.7 Clear and distinct and obscure and confused questions in DTOI

- 4.8 Primary quality questions in DTOI

- 4.9 Secondary quality questions in DTOI

- 4.10 Metaphysical and Ontological questions in DTOI

- 4.11 Ethical and aesthetic questions in DTOI

- 4.12 Sociological questions in DTOI

- 4.13 More obscure questions in DTOI

- 5 German Ideen Descartes — Stefanie Grüne

- 6 English translation Ideen Descartes — Stefanie Grüne

- 7 Stefanie Grüne on DTOI

- 8 False assumptions found in Descartes's theory of ideas

- 9 Key insight of the representational features of secondary quality sensations

- 10 Cartesian distinctions amongst ideas and their causes

- 11 Descartes on the Material Falsity of Ideas

- 11.1 Introduction

- 11.2 ChatGPT on material falsity in the Principles of Philosophy

- 11.3 Cartesian translations from Latin to English

- 11.4 Critique of Catherine Wilson's definition of material falsity

- 11.5 Gary Hatfield on material falsity

- 11.6 How Descartes avoids Arnauld's objections

- 11.7 Review of De Rosa on sensory representation by Elliott S. Paul and John Morrison

- 11.8 Rafaella De Rosa's annotated bibliography

- 12 On the Formal Reality/Objective Reality (Fr/Or) distinction

- 13 Cartesian Commentators on Descartes's theory of ideas

- 14 Descartes on thinking

- 14.1 Gary Hatfield on intellect over consciousness as the essence of thinking

- 14.2 Gary Hatfield on perception as the essence of thinking

- 14.2.1 (H1) What is the essence of thinking?

- 14.2.2 (H2) Consciousness as the essence of thought

- 14.2.3 (H3) The mind as an intellectual substance

- 14.2.4 (H4) What is the meaning of perception?

- 14.2.5 (H5) Is Hatfield right that comparing ideas with images suggests that all ideas represent?

- 14.2.6 (H6) Do all ideas always represent for Descartes?

- 14.2.7 (H7) Can there be Cartesian ideas that are NOT 'as if an image of a thing'?

- 14.2.8 (H8) Do all ideas 'in the strict sense' represent individual things?

- 14.2.9 (H9) Is the idea of substance an idea of an individual thing?

- 14.2.10 (H10) Are 'concepts' and 'simple notions' ever ideas and do they represent individual entities?

- 14.2.11 (H11) What makes something the central feature of something?

- 14.2.12 (H12) Are intellection, perception and representation synonymous?

- 14.2.13 (H13) Are intellection/perception/representation the central feature of thought?

- 14.3 What is the nature of thinking?

- 15 Primary versus secondary qualities

- 16 Descartes on Color

- 17 Descartes on secondary quality sensations as representations

- 18 Descartes on ideas

- 19 Descartes on the 'Ofness' of Ideas

- 20 What is intellectual content?

- 21 The Objective Reality of Ideas

- 22 Ontology of ideas, their objectively real mental contents, and the formally real objects

- 23 Descartes on thought

- 24 Idea as the form of a thought in Descartes

- 25 The content of Cartesian ideas

- 26 Are sensations ideas or not?

- 27 Obscure and confused sensations

- 28 Representations in Descartes

- 29 How are sensations representations?

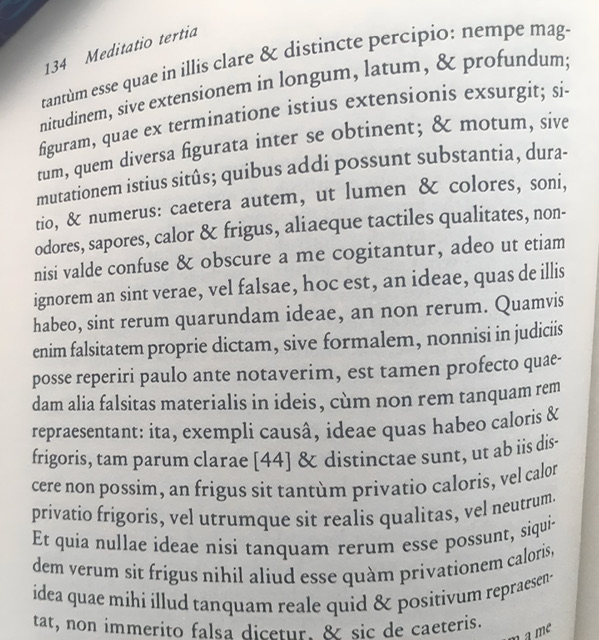

- 30 The meaning of cum non rem tanquam rem repraesantant

- 31 Why materially false ideas arise from nothing

- 32 Could Cartesian sensations intrinsically misrepresent?

- 33 Cecilia Wee on materially false ideas

- 34 Descartes on pain

- 35 How Descartes's four conceptions of an idea are related

- 36 Descartes's four conceptions of an idea discussed with ChatGPT (January 30 2023 version)

- 37 Descartes on innate ideas, objective reality, and material falsity of ideas discussed with ChatGPT-4 (February 13 2023 version)

- 38 ChatGPT-4 on exhibiting versus representing in Descartes's philosophy

- 39 Adam and Tannery English translation and Latin

- 40 DTOI Tools

- 41 Latin Translations

- 42 Critique of Wilfrid Sellars on DTOI

- 43 Descartes et les fausses idées by Emanuela Scribano

- 44 Dan Kaufman Review's David Clemenson's Descartes' Theory of Ideas

- 45 Alison Simmons on "Are Cartesian Sensations Representational?"

- 46 Dominik Perler's Descartes German/English translation

- 47 Passions of the Soul French/English translation

- 48 NOTES

Introduction to Descartes's Philosophy[edit]

Descartes had an uphill battle in philosophy. Having attended the newly open Jesuit Collège Royal Henry-Le-Grand at La Flèche from 1607 to 1614 starting when he was eleven years old, Descartes was well aware of the broad influence and firm establishment of Aristotelian and Aquinian doctrines that he needed to overthrow. At the wishes of his magistrate father, Joachim (1563–1640), René pursued a law career by graduating after two years at the University of Poitiers in 1616 with a Baccalauréat and Licence in canon and civil law. Perhaps this legal training contributed to Descartes's interest in methodological order. In any event, that Descartes needed to prosecute Aristotelian and Aquinian doctrines is emphasized by John Carriero in Michael Della Rocca's book review of Carriero's Between Two Worlds: A Reading of Descartes's Meditations (2009).

[John Peter] Carriero’s guiding contention is that we can achieve this kind of superior purchase on the text [an elegant and systematic reading of the Meditations] by taking seriously and prosecuting thoroughly the single idea that Descartes is driven throughout the Meditations by the desire to engage with scholastic Aristotelianism and, in particular, with the thought of Aquinas, the most influential proponent of scholastic Aristotelianism. As Carriero says,

- “the broad lines of Thomistic Aristotelianism helped to shape Descartes’s discussion—and set the stage for much of his major philosophical innovation more so than did other forms of Aristotelianism, or other traditions of thought.” (p. 6; emphasis mine)

Such engagement certainly led Descartes to deny fundamental tenets of Aquinas’s approach, but equally, as Carriero stresses, this engagement also led Descartes to adopt central planks of the Thomistic platform. It is Descartes’s encounter with Aquinas that, Carriero argues, provides the key to unlocking many of the puzzles about the Meditations that remain unsolved by previous ways of interpreting Descartes.[1] (bold not in original)

By the end of his philosophical career in 1644 Descartes softens his tone critiquing Aristotelian and Scholastic doctrines. With specific regard to Aristotelian principles, Descartes emphasizes in his correspondences that everything in his Principles of Philosophy (1644) is consistent with Aristotle's principles.

- “I know that people have thought my views were new; yet they will see here that I do not use any principles which were not accepted by Aristotle and by all those who have ever concerned themselves with philosophy. People have also imagined that my aim was to refute the received views of the Schools, and to try to render them absurd; but they will see that I do not discuss them any more than I would if I had never learnt them.” (AT IV, 141; CSMK 3, 238)

Four months later, again to Charlet, Descartes expresses his wish that the Principles would “serve effectively to explain the truths of the faith without, moreover, contradicting the writings of Aristotle.” (AT IV, 157; CSMK 3, 240) (bold not in original)

- It should be noted that, in regard to his Principles of Philosophy (1644), Descartes’ desire to have his textbook adopted and instituted into the Jesuit educational programme led him to soften his tone concerning the anti-Aristotelian and anti-Scholastic positions found in such works as his Discourse on the Method (1637) and Meditations (1641). Writing to his former teacher, Charlet, in October 1644, Descartes states in regard to the contents of his Principles that, “I know that people have thought my views were new; yet they will see here that I do not use any principles which were not accepted by Aristotle and by all those who have ever concerned themselves with philosophy. People have also imagined that my aim was to refute the received views of the Schools, and to try to render them absurd; but they will see that I do not discuss them any more than I would if I had never learnt them” (AT IV, 141; CSMK 3, p. 238); and four months later, again writing to Charlet, Descartes expresses his wish that his textbook would “serve effectively to explain the truths of the faith without, moreover, contradicting the writings of Aristotle” (AT IV, 157; CSMK 3, p. 240).

Descartes makes some serious mistakes regarding truths now known in cognitive science. The falsity of his position must be kept in mind because we don't believe it. Since he does, it is appropriate to remind ourselves that he dies when thinking what he has in mind for the mental. He writes that while the body decays and lessens functioning in old age, the mind remains entirely unaffected. Unfortunately, modern cognitive science has proven that bold Cartesian claim as drastically misguided and deeply false. Old age and brain disruptions from tumors, to vascular problems, disease, microbes, head trauma, hippocampal shrinking, etc. can all disrupt and effective any mind functions from intellect, sentience, perception, imagination, emotion, memory, or recognition.

QUOTE DESCARTES ON MIND NOT EFFECTED BY OLD AGE

Introduction to Descartes's Theory of Ideas[edit]

Descartes is recognized as a rational foundationalist,[2] utilizing his theory of ideas to accomplish numerous philosophical objectives. These objectives encompass refuting solipsism, establishing a solid intellectual groundwork for his mechanistic physics, and proving that God exists and is not a deceiver. His theory of ideas plays a crucial role in achieving all these aims. Consequently, it is essential for scholars studying Descartes to pursue a clear and distinct comprehension of his theories on ideas, particularly their representational attributes and functions.

Cartesian DTOI categories[edit]

Descartes's theory of ideas has several large category topics that this website will use to organize blog conversations of related interest. Although every DTOI category overlaps in sundry ways with others, it remains useful to catalog conversations with particular focuses of primary interest.

The Cartesian DTOI focus categories are listed first and any sub-categories listed under it are tags:

- Thoughts

- Consciousness

- Intellect

- Volition/Willing

- Passions/Emotions

- Ideas

- Ofness (ideas are of things)

- Consciousness/Awareness

- Form of a Thought

- Vivid/Clear (clara et distincta)

- Obscure/Confused

- Innate ideas

- Objective Reality

- Ontology

- Epistemology

- Material Falsity

- Representation

- Signs

- Misrepresentation

- Mind

- Mental Substance

- Pure Intellect

- Primary Attribute

- Primary and Secondary Qualities

Descartes on Ideas[edit]

-

In his Meditations on First Philosophy, Descartes uses the term 'idea' ten times in his "Preface to the Reader."[3]

In his Meditations on First Philosophy, Descartes uses the term 'idea' ten times in his "Preface to the Reader."[3]

-

The term "idea" and "ideas" occurs 716 times in Descartes's Objections and Replies. Of course, these are not all used by Descartes since the objectors themselves had many questions about Descartes's 'ideas.'

The term "idea" and "ideas" occurs 716 times in Descartes's Objections and Replies. Of course, these are not all used by Descartes since the objectors themselves had many questions about Descartes's 'ideas.'

MAKE A TABLE

All counts below are from Jonathan Bennett's translations of Descartes's first six sets of Objections and Replies

- Combining the numerical count from Jonathan Bennett's translation of the First (Caterus) Objections and Replies with Arnauld's, there are 111 uses of "idea" with 40 "ideas."

- Combining the numerical count from Jonathan Bennett's translation of the Third (Hobbes) Objections and Replies with Arnauld's Fourth set, there are 111 uses of "idea" with 40 "ideas."

- Fifth (Gassendi) Objections and Replies, 36 "idea": 36 17 "ideas."

- Combining the numerical count from Jonathan Bennett's translation of the Sixth (Mersenne and others) Objections and Replies, there are 36 uses of "idea" with 17 "ideas."

-

In Part I — Human Knowledge of The Principles of Philosophy idea and its plural occur 65 times.

In Part I — Human Knowledge of The Principles of Philosophy idea and its plural occur 65 times.

-

On the two hundred twenty-six pages of Descartes's Selected Correspondence (2017) translated by Jonathan Bennett, the word "idea" only occurs ten times and nothing of importance is said about them with the possible exception of his combining it in the phrase "ideas, or basic notions" in his "Correspondence with Princess Elizabeth" (p. 5).

On the two hundred twenty-six pages of Descartes's Selected Correspondence (2017) translated by Jonathan Bennett, the word "idea" only occurs ten times and nothing of importance is said about them with the possible exception of his combining it in the phrase "ideas, or basic notions" in his "Correspondence with Princess Elizabeth" (p. 5).

We should keep in mind that Descartes was a realist about mental phenomena, as emphasized by Gary Hatfield, as Hatfield sums up Descartes's legacy and contributions in Ch. 10 from his Routledge Guidebook.

Descartes was a realist about the mental. He was the ultimate realist because he posited a distinct mental substance. But leaving his two-substance ontology aside, he was a realist about mental phenomena themselves. Even before presenting any argument about the ontology of mental phenomena (whether they are, at bottom, immaterial or material), he affirmed the existence of thoughts, including feelings, sensations, imaginings, remembrances, desires, and volitions.[4] (bold not in original)

Someone might expect that after almost four centuries of examination (2023 – 1641 = 382), Descartes's[5] perspectives on the theory of ideas would be well-established. Regrettably, this is not the situation. Contemporary scholars of Descartes in North America, Canada, the United Kingdom, Europe, and Australia have yet to reach a consensus on the optimal interpretation of Descartes's thoughts on his theory of ideas.

The prolonged inability of professional philosophers over the span of nearly four centuries to reach a consensus on the interpretation of Cartesian texts could be attributed to several potential factors.

- (1) Inherently complex subject matter: The inherent complexity of the subject matter adds layers of difficulty. Those who specialize in the philosophy of mind, representation, and reference can corroborate the intricate nature of these studies.

- (2) Inconsistent Cartesian terminology: Secondly, the inconsistencies in Descartes's expression of his ideas could also contribute to this lack of consensus. For instance, early in his career, Descartes used the term "idea" to denote material images in the brain, as observed in AT VII: 171 and AT XI: 184. However, in his later works, he limited its usage to signify non-physical mental states. Moreover, he made three categories of distinctions, including formal/objective, material/formal, and material/objective, assigning dual meanings to the term "formal." In the formal/objective context, "formal" signifies 'actual existence,' while in the material/formal distinction, it connotes 'representational aspects.'

- (3) Early pioneer: Thirdly, understanding the complexity of issues regarding epistemology, ontology, or representation in relation to the mind and its features is no simple task. Furthermore, considering Descartes's role as an early modern pioneer, it is essential to grant him some leniency for any perceived inconsistencies or imperfections.

- Steven Nadler points out that Descartes himself acknowledged his inconsistent usage of the term 'idea'. Nadler writes:

Descartes is well aware of the ambiguities of the word 'idea.' In fact, his own use of the word is equivocal and inconsistent. He usually uses it to refer to immaterial images in the mind, and this is the understanding of the word which dominates the Meditations. . . . Sometimes, however, it is used also to refer to volitional acts by the mind; and at other times it is used to refer even to material images in the brain.[6] (bold not in original)

- Thus, a third reason for the continuing debates over Descartes's theory of ideas might be the need to reconcile his multiple statements on ideas and interpret them as a cohesive whole.

- (4) Cartesian interconnectedness: Kurt Smith gives a fourth reason for disagreement amongst Cartesian scholars due to the interconnectedness of Descartes's system. Smith suggests that when two commentators disagree over something it undoubtedly infects other features of their respective interpretations. When asked about diversity in views amongst Descartes scholars, Smith explains why it exists:

- We are a diverse group. Although we can agree on the basics—for instance, that Descartes was French, and that he held some form of mind-body dualism—there is an impressive divergence of views. The source of the diversity seems to be traceable to the fact that Descartes’s system is an interconnected conceptual system of various bits. Let’s say that you read or interpret one bit a certain way. That can (and probably will) effect how you understand the other bits. We don’t find two scholars agreeing on everything but just one bit. If two scholars disagree on how to read one bit, we’ll discover that they disagree on a lot more. For example, there are those who hold that Descartes thought there were many corporeal substances, while others disagree, positing that he believed in only one corporeal substance. In this view, bodies (plural) needs to be understood in light of what Descartes calls modal distinction. Some hold that Descartes took there to be an infinite number of innate ideas, others that he took there to be only three (the innate ideas of God, finite mind, and finite body), while some hold that he took there to be four (the innate ideas of God, finite mind, finite body, a union of mind and body).[7] (bold and bold italic not in original)

- (5) Sharing false assumptions: A fifth potential consideration for commentators continuous infighting may be due to their all sharing some common assumption that is false. A false assumption then infects the rest of a particular interpretation and forces that theory to twist and turn so as to remain consistent with the false assumption. Commentators end up fighting over these additional twists and turns when what really needs resolving is the discovery of that initial false assumption. Possible or actual false assumptions in Descartes's theory of ideas are investigated below.

- (6) Requiring a key insight: A sixth consideration may lie in needing a key insight into what Descartes was after to establish his overall philosophy. For what may be a key insight into Descartes's theory of ideas see below.

Descartes's definitions of thoughts and ideas[edit]

Descartes makes numerous pronouncements on ideas and thoughts. He appears to be inconsistent in his usage of the term 'idea' since he sometimes equates ideas with thoughts (in the Third Meditation) and even goes so far in the Second Replies to define an idea as the form of a thought. Other times, he restricts the use of the term 'idea' only to those thoughts that are "as if an image of a thing" [tanquam rerum imagines]. Each of these conceptions of a Cartesian idea are explored in this blog.

Andrew Pessin in his opening to the 2007/2008 edition of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy notes all of the turmoil Descartes generates amongst Cartesian scholars because of his inconsistent and complex presentation of his views on ideas.

- “Idea,” in its various linguistic forms, has been used in many ways by many philosophers, ancient, medieval, and early modern. Unfortunately for our current purposes, it was also used in many ways by Descartes himself. Exegesis of his views is, as a result, both a challenging and inescapably contentious affair. Amongst the many problems a complete exegesis would make sense of are these:

- Descartes's uses of the term “idea” diverge from perhaps the original or primary scholastic use:

- (1) He provides multiple non-equivalent definitions of the term, uses it to refer to as many as six distinct kinds of entities, and divides ideas inconsistently into various genetic categories.

- (2) He makes a trio of apparently inconsistent distinctions concerning ideas, invoking other opaquely employed scholastic concepts.

- (3) It's not clear that his “ideas” are consistent with his own ontology in general.

- (4) What he says about ideas suggests a “veil of perception” account of cognition, on which the cognizing mind is not directly “aware” of the external object itself, but only of some representative proxy; yet at the same time his texts sometimes indicate some form of direct cognition of the object itself.

- (5) Ideas' most important epistemic property—that of being clear and distinct—is ill-defined and poorly explicated, to the point that debates arise about whether and which ideas have this property.

- (6) To this day there are divergent interpretations of Descartes's account of sensory processes and ideas:

- (6a) concerning where and how he distinguishes between them and intellectual processes and ideas.

- (6b) whether sensory ideas have representational content.

- (6c) what Descartes means by the “material falsity” of some (or all?) sensory ideas.

- (6d) what the ontological status of “secondary” qualities is, etc.[8] (reformatted with parenthetical numbers added; bold not in original)

- (6a) concerning where and how he distinguishes between them and intellectual processes and ideas.

Cartesian commentators have typically noticed these inconsistencies and have labeled them as Descartes's use of the term 'idea' as occurring in a broader and a narrower sense.

Broad sense of idea[edit]

Here are examples of the broad use of ideas:

For instance, the first time Descartes writes of ideas in the Meditations on First Philosophy proper (not including his "Preface to the Reader"), is in the Third Meditation. For clarification, I insert in square brackets the particular kind of mental items referenced in the quotation.

- . . . the earth, sky, stars, and everything else that I took in through the senses [namely, sensations]—but in those cases what I perceived clearly were merely the ideas or thoughts of those things that came into my mind [again, these are all sensations]; and I am still not denying that those ideas [sensations referenced as ideas] occur within me. But I used also to believe that my ideas came from things outside [these would be sensations stimulated by external physical causes] that resembled them in all respects.[9] (bold not in original)

According to the above, sensations can be perceived clearly.[10] Also, Descartes uses the phrase "ideas, or thoughts" which shows his term 'idea' can be used interchangeably with his term 'thought,' at least in this context. Consequently, an idea in the broad sense can be used to apply to any mental event and often Descartes uses that term interchangeably with the term 'thought.'

The next two sentences that follow the previous quotation reveal that perceptions can be caused by sensations and sensations have insufficient strength to reveal whether what they represent is true or false.

- Indeed, I believed this for so long that I wrongly came to think that I perceived it clearly. In fact, it was false; or anyway if it was true it was not thanks to the strength of my perceptions.

What is wrong with sensations that prevents them from having sufficient 'strength' for perceiving what they truly represent? My answer is that we can account for the lack of sensory perceptual strength were these sensations to lack having any objectively real mental content. Failing to have an objectively real object of thought means there there is no choice for what the experiencer is thinking about that indicates its referent. Whenever one has an idea of a goat, it is known immediately that one is thinking about a goat.[11] However, when experiencing a sensation of cold from holding an ice cube, one is immediately and directly aware of a phenomenally cool experience, yet one remains ignorant of what properties or modifications of the physical properties of that ice cube is causing you to experience coolness.

The conclusion of ideas being any mental event gets reinforced when Descartes defines an idea as the form of a thought in his second Replies to Objections in geometrical form. Since every thought always has a form that gives that thought whatever mental characteristics had by this particular thought and it is this form that one is aware of when having such a thought it follows that to absolutely every thought there is an idea that one is aware of when having that thought since the form of that thought determines what one can be aware of when having that thought.

Since every thought has a form that one is immediately and directly aware of when having that thought there is no problem of an infinite regress requiring one be aware of the idea of the idea of the idea to infinity. Each awareness of a thought does not require another idea to be aware of it, leading to an unending chain. Because the form of a thought is directly present to a mind without the need for another intermediary thought this direct presence prevents an infinite regress, as the idea, in this sense, is not a separate entity from that thought but rather the very mode or manner in which the thought is given to conscious awareness. The Meditations, particularly the Third Meditation, emphasizes the direct and immediate awareness of one's own thoughts.

Furthermore, there is no potential confusion between a thought and thoughts about thoughts (or meta-thoughts, or second order ones) within Descartes's framework. If an idea is the form of a thought, this does not blur the distinction between experiencing a thought and thinking about that thought because there is a clear distinction between experiencing a thought and reflecting upon it. An idea as the form of a thought is the immediate and intrinsic way the thought is presented to the mind. In contrast, a second-order thought would involve a reflective act, a conscious turning of the mind upon its own contents and it would have a different form. Because Descartes emphasizes that awareness of the form of a thought is direct and non-mediated and by distinguishing between immediate first order experience and reflection upon them Descartes avoids the pitfalls of any infinite regress or any confusion between first and second-order thoughts.

At the start of his Third Meditation Descartes reviews what he invludes under the category of a thinking thing.

- “I am a thing that thinks: that is, a thing that doubts, affirms, denies, understands a few things, is ignorant of many things, is willing, is unwilling, and also which imagines and has sensory perceptions; for as I have noted before, even though the objects of my sensory experience and imagination may have no existence outside me, nonetheless the modes of thinking which I refer to as cases of sensory perception and imagination, in so far as they are simply modes of thinking, do exist within me m—of that I am certain.”[12]

Next, Descartes also claims that his term 'idea' can have a very broad application to all thought types whether those thought types sources are innately derived, resulting from stimulation from external objects, or constructed by own's own mind as when one uses her imagination.

-

"By the term 'idea' I understand all that can be in our thought; and I distinguish three sorts of ideas according to their origin, for they are derived either from innate sources, or from external objects, or from our own mental activities."[13] (bold not in original)

"By the term 'idea' I understand all that can be in our thought; and I distinguish three sorts of ideas according to their origin, for they are derived either from innate sources, or from external objects, or from our own mental activities."[13] (bold not in original)

If idea means absolutely everything that can be in our thought what is it that is mental that cannot be in thought? There is nothing that can be mental or in someone's mind that cannot be thought, according to Descartes. Since there could not be any thought that did not have a form, every thought has an idea that is what has the mind being conscious of that very thought.

-

"but in those cases what I perceived clearly were merely the ideas or thoughts [ideas, sive cogitationes] of those things that came into my mind; and I am still not denying that those ideas occur within me."[14] (bold not in original)

"but in those cases what I perceived clearly were merely the ideas or thoughts [ideas, sive cogitationes] of those things that came into my mind; and I am still not denying that those ideas occur within me."[14] (bold not in original)

-

"."[15] (bold not in original)

"."[15] (bold not in original)

-

"."[16] (bold not in original)

"."[16] (bold not in original)

-

"."[17] (bold not in original)

"."[17] (bold not in original)

-

"."[18] (bold not in original)

"."[18] (bold not in original)

-

"."[19] (bold not in original)

"."[19] (bold not in original)

In The Principles of Philosophy, Part I, Principle 9, Descartes writes:

9. What is meant by ‘thought’. I take the word ‘thought’ to cover everything that we are aware of as happening within us, and it counts as ‘thought’ because we are aware of it. That includes not only understanding, willing and imagining, but also sensory awareness.[20] (bold not in original)

- "By the word idea, we mean whatever is immediately perceived by the mind." (Descartes, The Principles of Philosophy, translated by John Cottingham, Robert Stoothoff, and Dugald Murdoch (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 193)

- "Well, then, what am I? A thing that thinks. What is that? A thing that doubts, understands, affirms, denies, wants, refuses, and also imagines and senses."[21]

If thoughts are ideas then a thinking thing has ideas when it does any of the items found in Descartes's list.

Cartesian commentators have said that Descartes does use his term 'idea' to cover a broad swath of mental states. For example, Earline Jennifer Ashworth in her 1972 article "Descartes' Theory of Clear and Distinct Ideas" in Cartesian Studies, edited by Ronald Joseph Butler, 89–105 has said:

- "The fact that Descartes adopted the word ‘idea’ is itself significant. . . . Descartes took the word ‘idea’ and applied it to the contents of the human mind because he wanted to escape the suggestion that these contents must be in some sense dependent on the external world as a causal agent. He wished to establish the logical possibility that a mind and the ideas contained within it are unrelated to other existents, and can be discussed in isolation from them.

- Descartes saw the term ‘idea’ as having a very wide extension.

- He said “ . . . I take the term idea to stand for whatever the mind directly perceives,” where the verb ‘perceive’ refers to any possible cognitive activity, including sensing, imagining and conceiving. Thus a sense datum, a memory, an image, and a concept can all be called ideas. This, of course, leads to the blurring of distinctions. For Descartes, “I have an idea of red” may mean that I am now sensing something red, or that I have a concept of the colour red, even if I am not now picking out an instance of that concept. Moreover, when Descartes speaks of an idea, he may be taking it as representative of some object or quality in the physical world, as when he says “I have an idea of the sky and stars,” or he may be referring to the meaning he assigns to a word, as when he says “I have an idea of substance.” Nor does he make any distinction between “having an idea” and “entertaining a proposition.” Such statements as “Nothing comes from nothing” and “The three angles of a triangle are equal to two right angles” are categorized as ‘common notions,’ and are included among the contents of the mind. Descartes does remark that in some cases an idea may be expressed by a name, in other cases by a proposition, but he does not bother to pursue this line of inquiry." [22] (bold not in original)

Narrower sense of idea[edit]

At other times Descartes states that he wishes to restrict his use of the term 'idea' to a more limited class of his thoughts, namely those thoughts that are as if images of things [tanquam rerum imagines], although Descartes vigorously denies that this aspect must be identical to an image.[23]

- "First, if I am to proceed in an orderly way I should classify my thoughts into definite kinds, and ask which kinds can properly be said to be true or false. Some of my thoughts are, so to speak, images or pictures of things—as when I think of a man, or a chimera, or the sky, or an angel, or God—and strictly speaking these are the only thoughts that should be called ‘ideas’."[24] (bold not in original)

Here is a crucial distinction Descartes informs his readers to be aware of when the term 'idea' is used.

The second objection is that it does not follow, from my possessing the idea of a thing more perfect than I am, that the idea itself is more perfect than myself, and much less that what is represented by the idea exists. But I reply that in the term idea there is here something equivocal; for it may be taken either materially for an act of the understanding, and in this sense it cannot be said to be more perfect than I, or objectively, for the thing represented by that act, which, although it be not supposed to exist out of my understanding, may, nevertheless, be more perfect than myself, by reason of its essence.[25] (bold not in original)

He writes in Meditations on First Philosophy, Meditation III about what counts as ideas in thought:

- "By the term 'idea' I understand all that can be in our thought; and I distinguish three sorts of ideas according to their origin, for they are derived either from innate sources, or from external objects, or from our own mental activities." (René Descartes, Meditations on First Philosophy, trans. John Cottingham, Cambridge University Press, 1986, p. 25) (bold not in original)

Descartes often uses his term 'idea' to stand for any mental event and often uses that term interchangeably with the term 'thought.'

- "but in those cases what I perceived clearly were merely the ideas or thoughts of those things that came into my mind; and I am still not denying that those ideas occur within me."[26] (bold not in original)

- None of your [Thomas Hobbes] subsequent discussion concerning ideas needs to be answered, since you restrict the term 'idea' to images depicted in the imagination, whereas I extend it to cover any object of thought. [27] (bold not in original)

In the Fourth Objections, Antoine Arnauld objects to how Descartes understands the awareness of ideas. Arnauld asserts:

Objection (3): Let me add something that I missed earlier. Descartes lays it down as certain that there can be nothing in him, considered as a thinking thing, of which he isn't aware, but it seems to me that this is false. For by 'himself, considered as a thinking thing' he means simply his mind, considered as distinct from the body. But surely we can all see that there may be many things in our mind of which the mind isn't aware. To give one example out of ever so many: the mind of an infant in its mother's womb has the power of thought, but isn't aware of it.[28] (bold not in original)

Descartes reacts to these objections by explaining that what he believes is that "the mind, considered as a thinking thing, can't contain anything of which it isn't aware."

Reply (3): Arnauld's third and last point concerns my saying that 'there is nothing in the mind of which we aren't aware'. I meant this to refer to the operations of the mind, but Arnauld takes it to apply to the mind's powers, and so denies it. It seems to me self-evident that the mind, considered as a thinking thing, can't contain anything of which it isn't aware. We can't make sense of the proposition that the mind, seen as a thinking thing, contains something that isn't a thought or something dependent on a thought. . . . and we can't have any thought that we aren't aware of at the very moment when it is in us. Which is why I am sure that the mind begins to think as soon as it is implanted in the body of an infant, and that it is immediately aware of its thoughts, even though it doesn't remember this afterwards because the impressions of these thoughts don't remain in the memory. But although we are always actually aware of the acts or operations of our minds, we aren't always aware of the mind's faculties or powers, except potentially. By this I mean that when we concentrate on employing one of our faculties, then we immediately become actually aware of it, if the faculty in question resides in our mind. So we can say: it's not in the mind if we aren't capable of becoming aware of it.[29] (italics in Bennett; bold and bold italic not in original)

Descartes last point certainly rules out anything such as unconscious thoughts being in a mind and even goes so far as to label 'unconscious thoughts' as a blatant contradiction since it is impossible, according to Descartes, for thoughts that one is unaware of to be possible. It also supports what has come to be called the incorrigibility thesis that one cannot be mistaken, hence 'corrected', regarding the contents of one's own occurrent thoughts. It also seems to support a transparency of the mind to itself doctrine, although some scholars such as Gary Hatfield dispute that Descartes supported the transparency doctrine.

- "."[30] (bold not in original)

- "."[31] (bold not in original)

- "."[32] (bold not in original)

- "."[33] (bold not in original)

At other times Descartes states that he wishes to restrict his use of the term 'idea' to a more limited class of his thoughts, namely those thoughts that are as if images of things [tanquam rerum imagines].

First, if I am to proceed in an orderly way I should classify my thoughts into definite kinds, and ask which kinds can properly be said to be true or false. Some of my thoughts are, so to speak, images or pictures of things—as when I think of a man, or a chimera, or the sky, or an angel, or God—and strictly speaking these are the only thoughts that should be called ‘ideas’."[34] (bold not in original)

Descartes vigorously denies that this aspect of being 'as if an image' is identical to literally being an image when clarifying his position on this matter to Thomas Hobbes in the Third Replies to Objections.

None of your subsequent discussion concerning ideas needs to be answered, since you restrict the term 'idea' to images depicted in the imagination, whereas I extend it to cover any object of thought. [35] (bold not in original)

Reply (5): Hobbes wants the term 'idea' to be used to refer only to the images of material things that are portrayed in the corporeal imagination; and with this on board he can easily 'prove' that there can't be any proper idea of an angel or of God. But I make it quite clear in several places throughout the Meditations, and especially in this very place, that I take 'idea' to refer to whatever is immediately perceived by the mind. For example, when I want (or fear) something, I simultaneously perceive that I want (or am afraid); and that's why I count wanting and fearing among my ideas. I used the word 'idea' because it was the term that philosophers standardly used to refer to the kinds of perception belonging to the divine mind, although we recognize that God doesn't have any corporeal imagination. And I had no more appropriate term at my disposal.[36] (bold not in original)

In René Descartes's theory of ideas, he often speaks about and even defines what he means by idea and by thought. For example, he sometimes uses his term 'idea' to apparently be interchangeable with his term 'thought' as in these quotations from his Third Meditation:

“By the term 'idea' I understand all that can be in our thought; and I distinguish three sorts of ideas according to their origin, for they are derived either from innate sources, or from external objects, or from our own mental activities."“ . . . but in those cases what I perceived clearly were merely the ideas or thoughts of those things that came into my mind; and I am still not denying that those ideas occur within me.”[37] (bold not in original)

Yet at other times Descartes claims to restrict how his term 'idea' should be used so it does not apply to any mental event, but only to those that are representational thoughts that are "as if an image of a thing" (tanquam rerum imagines) (CSM II: ?; AT VII: ?).

How can a Cartesian commentator reconcile these broad and narrower uses of Descartes's term 'idea'? Are they contradictory or inconsistent, or not?

Relationships between the broad and narrow senses of Cartesian ideas[edit]

Descartes's usage of 'thought' (cogitatio) is broad and encompasses a variety of conscious mental operations. For instance, in his Meditations on First Philosophy, he writes, "By the word 'thought,' I understand all that of which we are conscious as operating in us. And that is why not alone understanding, willing, imagining, but also feeling, are here the same thing as thinking [cogitare] (AT VII, 28; CSM II, 18).

Descartes often uses 'idea' just as broadly, equating it with any content of thought. For instance, in the Third Meditation, he states, "By the term 'idea,' I understand all that can be in our thought" (AT VII, 37; CSM II, 25).

In the broad sense, Descartes uses 'idea' as a stand-in for 'thought'. He defines 'idea' as "all that can be in our thought," which includes any mental content or cognitive occurrence. It is used in a generic way to refer to all kinds of thoughts, no matter what they represent or how they come about.

However, in a narrower sense, Descartes uses 'idea' to mean only those thoughts that represent something, like an image represents a thing. This usage is more specialized, focusing on the aspect of thought that especially deals with representation. In this sense, not all thoughts are ideas, but only those that have an intellectual representational dimension.

How should these seemingly conflicting uses of 'idea' get reconciled? It is important to understand that Descartes's method is often contextual. He adjusts his terminology according to the philosophical problems he is addressing. The 'broad' and 'narrow' senses of 'idea' do not reflect outright inconsistency in Descartes's thought, but rather the flexibility of his philosophical method.

Furthermore, Descartes doesn't seem to claim that these two senses of 'idea' are mutually exclusive. Even in the broader sense, ideas may still be about something in two ways—directly about or indirectly about.

- (1) DIRECTLY ABOUT: an idea can be about its immediately perceived/experienced mental content, or (2) INDIRECTLY ABOUT: a sensory idea (a sensation) might be about something by being a sign for a particular configuration of particles in motion that causes this sensation, so that it is a representation—even if not in the 'image of a thing' sense.

One could understand the broader definition as a general category, within which the narrower definition is a specialized subset.

However, I would disagree with anyone who claimed that when comparing the broader sense of ideab with the narrower one (idean) where the narrower one satisfies the tanquam rerum imagines condition that even the broader use requires that every ideab must always have a mental content because even ideasb are still about or of something—so they still can be about something, even if not in the 'image of a thing' sense." Just by being "about something" does not entail that it is serving a representational function since a coolness sensation can be of coolness without that coolness being a representation of that coolness. Rather, the coolness is presenting a coolness experience and not representing one. If the coolness merely represented coolness then it would not be required that a perceiver was experiencing coolness just like representing a pain by thinking a thought about pain does not entail that one is hurting at that time.

So, the concept of being "about something" doesn't automatically imply any representational function. For example, when experiencing a sensation of coolness, that sensation is indeed a direct experience rather than a representation of coolness.

To reconcile these points, let's return to a Cartesian distinction. In the broader sense, 'ideab' could be seen as covering any contents of mind, including sensations, judgments, acts of imagination, or emotions. These are 'ideasb' because they occupy one's conscious attention—they are "in our thought," as Descartes says.

But when Descartes talks about 'ideasn' in a narrower sense—as representations or 'as if images of things' [tanquam rerum imagines]—he's focusing on a subset of mental contents: those thoughts which aren't just direct experiences or activities of the mind, but are specifically representational in nature. So sensations of coolness or pain might fall under 'ideasb' in the broader sense, but not in the narrower sense.

The ideas in narrower sense all contain objective reality.

➢ How does Descartes distinguish between thoughts and ideas?

'Thought' is the broadest category: 'Thought' (cogitatio) is used by Descartes in a very general sense to include everything that happens in our mind when we are conscious. This includes not only understanding, but also imagining, sensing, willing, affirming, denying, and even doubting. In other words, for Descartes, all mental operations that we are aware of could be classified as 'thought.'

'Idea' is a subset of 'thought': Descartes uses the term 'idea' to refer to a specific kind of thought. In the Third Meditation, Descartes says: "By the term 'idea' I understand all that can be in our thought." When he refers to 'idea,' he specifically means a thought as it represents something else to the mind.

While every idea is a thought (in the sense that it is a part of our conscious mental operations), not every thought is an idea (because thoughts can include many mental operations that do not involve representing something else to the mind).

Descartes does sometimes use 'idea' and 'thought' in ways that can appear interchangeable, but a closer reading of his work suggests that he sees 'idea' as a specific kind of 'thought.'

In the Third Meditation, for instance, Descartes says, "By 'idea,' I understand all that can be in our thought." Here, 'idea' is seemingly used as a catch-all term for any content of thought. However, in other passages, Descartes seems to use 'idea' in a more limited sense, referring specifically to thoughts that represent something else.

With that said, it seems accurate to say that, for Descartes, all ideas are thoughts (since ideas are contents of thought), but not all thoughts are ideas (since some thoughts, such as acts of volition or doubting, do not represent anything else and thus wouldn't count as 'ideas' in the narrower sense). This suggests that 'idea' is a subset of 'thought'—at least in some contexts. However, Descartes also sometimes uses 'idea' more broadly to refer to any content of thought, which would make it seem like 'idea' and 'thought' are interchangeable.

If not all thoughts are ideas (since some thoughts, such as acts of volition or doubting, do not represent anything else and thus wouldn't count as 'ideas' in the narrower sense), this suggests that 'idea' is a subset of 'thought.' But ideas are not subsets of thoughts given Descartes's definition of ideas in his geometrical exposition in his Objections and Replies where he defines an idea as the form of a thought. Since every thought has a form, every thought has or is an idea. In the Replies to the Second Set of Objections to his Meditations, Descartes defines an idea as "the form of any given thought, immediate perception of which makes us aware of the thought." This statement indicates that an idea is an integral component of any thought and not merely a subset of thought.

In this light, every thought has an idea as its form, or the content that is present to the mind. Under this definition, one could understand an idea as the specific content or form that a thought takes, while the thought is the broader mental event or act that encompasses this content. In this sense, the term 'idea' would indeed apply to every thought, because every thought has some form or content.

Nevertheless, Descartes still does occasionally use the term 'idea' in a narrower sense, to refer only to those thoughts that represent something else. Whenever Descartes does this I believe it is because every one of these narrower types of idea contains objectively real mental and it is by having such objective reality that makes that thought be as if an image of a thing.

This doesn't necessarily contradict his definition of an idea as the form of a thought; it could be seen as simply a more specific usage of the term 'idea'.

'Idea' in the narrower sense: When thinking of an apple, for instance, Descartes would say you are having an 'idea' of an apple, where the 'idea' is the mental representation of the apple.

Examples of thoughts that are not ideas in the narrower sense: These could include acts of volition (like deciding to go for a walk), doubting (such as questioning the existence of the external world), feeling (like experiencing a sensation of pain or pleasure), and other mental operations that don't involve forming a representation of something else.

In his Replies to the Second Set of Objections, Descartes suggests a different relationship between thoughts and ideas, defining an idea as "the form of any given thought, immediate perception of which makes us aware of the thought" (AT VII, 160; CSM II, 113). In light of this definition, every thought would have an idea as its form or content, suggesting that 'idea' and 'thought' are not merely subset and set, but are integrally connected.

Descartes, René. The Philosophical Writings of Descartes, translated by John Cottingham, Robert Stoothoff, Dugald Murdoch and Anthony Kenny, 3 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984-1991. References to Descartes’s works are by volume and page number(s) of this edition, which appear in the text as (AT volume, page; CSM volume, page).

As per Descartes's definitions, every thought has an idea as its form. As mentioned earlier, in the Replies to the Second Set of Objections, Descartes states that an idea is "the form of any given thought, immediate perception of which makes us aware of the thought" (AT VII, 160; CSM II, 113). Thus, in a broad sense, every thought would have an idea as its form or content, making 'idea' an integral part of 'thought' rather than a separate subset.

However, it's crucial to note that Descartes occasionally applies 'idea' in a narrower context, where it has a representational content. In such a context, not every thought would necessarily be an idea; for instance, acts of volition or doubting, which do not represent anything, might not fall under 'idea' in this stricter sense.

What would an idea that is not a thought be like for Descartes?

Based on Descartes's philosophical framework, it's hard to conceive of an 'idea' that is not a 'thought.' In Descartes's philosophy, an idea is inherently a mental entity, the form or content of a thought. In his Replies to the Second Set of Objections, he defines an idea as "the form of any given thought, immediate perception of which makes us aware of the thought" (AT VII, 160; CSM II, 113).

In this sense, an idea cannot exist independently of a thought; it is an inherent part of the thought. Even when Descartes uses 'idea' in a narrower sense, to refer to thoughts that represent something else (as in the thought of X), the 'idea' still needs to be part of a 'thought' process in order to exist in the mind.

So, according to Descartes's philosophical framework, there wouldn't be an 'idea' that is not also a 'thought.' An idea, by definition, is a form or component of thought in Descartes's philosophy. Thus, an 'idea' that is not a 'thought' would seem to contradict Descartes's understanding of these terms.

Alan Gewirth when discussing Descartes's views on the clarity and distinctness of ideas baldfacedly claims that for Descartes anything one is aware of in the mind is an idea. Yet Gewirth in the very next sentence appears to require that every idea is representational by being "like an image of a thing." It would follow from these two claims that any idea that is the result of being a direct object of the mind's perception is as it were an image of a thing and therefore representational. But this cannot be correct since Descartes informs his readers that in the case of his emotional states, such as the fear of a lion, while the lion is in the mind by way of representation, the fear aspect of this thought is something more and therefore other than a representational state even though that aspect is part of Descartes's thought that constitutes his fear of a lion.

“Other thoughts have more to them than that: for example when I will, or am afraid, or affirm, or deny, my thought represents some particular thing but it also includes something more than merely the likeness of that thing. Some thoughts in this category are called volitions or emotions, while others are called judgments."[38]

Descartes is consistent in holding that there is more to his cognition and subsequent awarenesses involved in his fear of a lion than just an awareness of a representation of a lion in his reply to Thomas Hobbes.

Hobbes objected to Descartes's claim that when a person fears a lion that the relevant mental state included awareness of a non-representational fear aspect. Hobbes instead claims that in a fear of a lion there is only a representation of a charging lion and the non-mental physiological response of flight. In his sixth objection, Hobbes first quotes the passage from Descartes then gives his objection to it.

Objection (6): 'Other thoughts have more to them than that: thus when I will, or am afraid, or affirm, or deny, my thought represents some particular thing but it also includes something more than merely the likeness of that thing. Some thoughts in this category are called volitions or emotions, while others are called judgments.' When someone wills, or is afraid, he has an image of the thing that he fears or the action that he wills; but what is the 'something more' that his thought includes? This isn't explained. Even if fear were a thought, I don't see how it could be anything but the thought of the thing we are afraid of. For fear of a charging lion' is nothing but the idea of a charging lion together with the effect that this idea has on the heart, which in turn causes in the frightened man the animal motion that we call 'flight'. And this motion of fleeing is not a thought; so we are left with the conclusion that fear doesn't involve any thought except the thought that portrays the thing feared. And the same applies to willing.[39]

Descartes strongly disagrees that the only cognitive aspect of which the fearer is aware of is that of a charging lion and requires that one is additionally aware of the fear and this includes something over and above the charging lion idea and the physiological reactions of an accompanying racing heart.

Reply (5): Hobbes wants the term `idea' to be used to refer only to the images of material things that are portrayed in the corporeal imagination; and with this on board he can easily `prove' that there can't be any proper idea of an angel or of God. But I make it quite clear in several places throughout the Meditations, and especially in this very place, that I take `idea' to refer to whatever is immediately perceived by the mind. For example, when I want (or fear) something, I simultaneously perceive that I want (or am afraid); and that's why I count wanting and fearing among my ideas.Reply (6): It is self-evident that seeing a lion while being afraid of it is different from simply 'seeing it'; and that 'seeing a man run' is different from 'silently affirming to oneself that one sees him.' I don't see anything here that needs answering.[40] (bold not in original)

“The direct object of the mind's act of perception is for Descartes always an idea.7 Footnote 7. " . . . ostendo me nomen ideae sumere pro omni eo quod immediate a mente percipitur. [ . . . showing that I take the name of idea for everything that is immediately perceived by the mind.] IIIae Resp., VII, 181. [41] (bold not in original)

Ideas, however, have a double status: on the one hand, they are themselves existents, "formal essences," modes of thought; on the other hand, they are significances, "objective essences," representative of things other than themselves.8 Footnote 8. Med. III, VII, 40 ff. Cf. ibid., 37: Quaedam ex his (cogitationibus) tanquam rerum imagines sunt, quibus solis proprie convenit ideae nomenclature. [Some of these (thoughts) are like images of things, to which only the name of idea properly applies.][42] (bold not in original)

So, on this reading of 'idea', since all mental states for Descartes are 'immediately perceived by the mind' every mental state can be called an idea. Descartes reinforces these impressions of the general applicability of the term 'idea' to any of his mental states when he claims that:

- These activities are all aspects of my thinking, and are all inseparable from myself. The fact that it is I who doubt and understand and want is so obvious that I can’t see how to make it any clearer. But the ‘I’ who imagines is also this same ‘I’. For even if (as I am pretending) none of the things that I imagine really exist, I really do imagine them, and this is part of my thinking. Lastly, it is also this same ‘I’ who senses, or is aware of bodily things seemingly through the senses. Because I may be dreaming, I can’t say for sure that I now see the flames, hear the wood crackling, and feel the heat of the fire; but I certainly seem to see, to hear, and to be warmed. This cannot be false; what is called ‘sensing’ is strictly just this seeming, and when ‘sensing’ is understood in this restricted sense of the word it too is simply thinking.[43] (bold and bold italic not in original)

Yet, in other places, Descartes claims to restrict the use of the term 'idea' to a more restrictive domain of his thoughts as when he writes that:

- "Some of my thoughts are, so to speak, images or pictures of things—as when I think of a man, or a chimera, or the sky, or an angel, or God—and strictly speaking these are the only thoughts that should be called ‘ideas.’"[44] (bold not in original)

The list provided are presumably all non-sensory intellectual mental states found only in the non-sensory intellect and nowhere else in the mind. In the restricted sense, there would be no ideas used as names of any mental events that are imaginations, willings, emotional states, or sensations.

Nevertheless, Descartes continues to label individual thoughts in the list of imaginations, willings, emotional states, and sensations as ideas.

Janet A. Boyle on ambiguity in Descartes's ideas[edit]

Descartes on Innate Ideas by Deborah A. Boyle

1.1 Ambiguities in Descartes' Idea of 'Idea'

In their objections to the Meditations, both Hobbes and Gassendi evidently take 'idea' to be equivalent to 'image' (CSM II 126-7/AT VII 179 and CSM II 253/AT VII 366). In defense of his use of this apparently puzzling term, Descartes writes in his Replies to Hobbes:

- I used the word 'idea' because it was the standard philosophical term used to refer to the forms of perception belonging to the divine mind, even though we recognize that God does not possess any corporeal imagination. And besides, there was not any more appropriate term at my disposal. (CSM II 127-8/AT VII 181)

As this remark makes clear, Descartes means the word 'idea' to refer to a mode of thought, and not to a mode of extended substance. Descartes writes in the Second Set of Replies that:

- it is not only the images depicted in the imagination which I call 'ideas'. Indeed, in so far as these images are in the corporeal imagination, that is, are depicted in some part of the brain, I do not call them 'ideas' at all; I call them 'ideas' only in so far as they give form to the mind itself, when it is directed towards that part of the brain. (CSM II 113; AT VII 160-61)

This was certainly true of the Meditations and Descartes' later works. However, in his early works, such as the Rules for the Direction Of the Mind, the World, and the Treatise On Man, Descartes used 'idea' in a quite different sense, to characterize modes of both corporeal and incorporeal substances. In other words, 'idea' in the earlier works is ambiguous between a corporeal and an incorporeal sense. Thus in a discussion of our mental faculties in the Rules (probably written before 1629), Descartes writes:

- Thirdly, the 'common' sense functions like a seal, fashioning in the phantasy or imagination, as if in wax, the same figures or ideas which come, pure and without body, from the external senses. The phantasy is a genuine part of the body, and is large enough to allow different parts of it to take on many different figures and, generally, to retain them for some time.4 (CSM I 41–42; AT X 414)

If the phantasy is a part of the body, a corporeal substance, and if ideas can be fashioned in the phantasy, then those ideas must also be corporeal. In The World, written between 1630 and 1632, Descartes consistently uses 'idea' to refer to a mode of mental substance, but he typically uses the phrase 'the ideas we have in our mind.' That he felt the need to specify that he meant ideas in the mind suggests that he thought there could be ideas in the body, too. And, indeed, just such a usage appears in the Treatise on Man, which he probably began to write in late 1632. There, Descartes explains how the mechanism of the human body would operate even without being joined to a rational soul. In his account of sensation, he calls the images which are formed in the corporeal imagination 'idees' (CSM I 106; AT XI 176), and he explicitly states, `"I wish to apply the term "idea" generally to all the impressions which the spirits can receive as they leave gland H [the location of the imagination and the "common" sense]" (CSM I 106; AT XI 177). The 'spirits' in this account are corporeal entities, and the 'impressions' they receive are, apparently, a physical configuration imparted to them. Thus the word 'idea' is being used to describe a brain occurrence, something corporeal rather than something in the soul.

This vacillation between two senses of 'idea' could be explained if Descartes had not yet worked out his doctrine that mental substance is distinct from bodily substance. And, in fact, there is little evidence that at the time of writing the Rules Descartes had clearly formulated his doctrine of two substances; if this is right, then there would have been no reason for him to restrict 'idea' to one substance rather than the other. We can see the beginnings of the two-substance doctrine in The World and the Treatise On Man. But only when he began to explore the ramifications of a two-substance doctrine, around the time of the Meditations, would Descartes have realized that he needed either to restrict 'idea' to a purely mental sense, or to emphasize that the term has two senses; the passage from the Second Replies shows that he chose the first of these options. By the time of the Meditations, Descartes is quite emphatic that by 'idea' he means a mode of thought.

Yet an important ambiguity remains in Descartes' use of the term 'idea' in the later works. While he does consistently use 'idea' in the later works to characterize mental rather than physical phenomena, he points out in the Preface to the Meditations that "Idea" can be taken materially, as an operation of the intellect. . . . Alternatively, it can be taken objectively, as the thing represented by that operation' (CSM II 7; AT VII 8). In other words, 'idea' might refer to an act of thinking, or it might refer to the object of that act. In referring to someone's idea of a horse, for example, Descartes might mean to refer to the act whereby the person thinks of the horse (the idea in the material sense), but he might also mean to refer to the object of the person's thought—that is, to the horse being represented (the idea in the objective sense). In his paper "The Theory of Ideas," Vere Chappell rightly points out that this distinction is 'the key to understanding Descartes' whole theory of ideas, which itself is the central component of his theory of knowledge?' Chappell also usefully abbreviates 'idea in the material sense' and 'idea in the objective sense' as ideam and ideao, respectively, a convention I shall adopt. The distinction between ideasm and ideaso should be borne in mind whenever Descartes refers to ideas. Consider Descartes' definition of 'idea' in the Second Set of Replies:

- I understand this term to mean the form [formam] of any given thought, immediate perception of which makes me aware of the thought. Hence, whenever I express something in words, and understand what I am saying, this very fact makes it certain that there is within me an idea of what is signified by the words in question. (CSM II 113/AT VII 160)

In the same passage, he says that 'thought' means 'everything that is within us in such a way that we are immediately aware of it. Thus all the operations of the will, the intellect, the imagination, and the senses are thoughts' (CSM II 113; AT VII 160). If, as he says here, operations of the intellect are 'thoughts,' and (as he says in the Preface to the Meditations) ideasm are operations of the intellect, then thoughts must be ideasm. But when he characterizes ideas as the 'forms' of particular thoughts, is he referring to ideasm, or ideaso? I think Descartes' use of the term 'form' is a clue that he is referring in this case to ideaso. Although Descartes explicitly rejects scholastic forms in his account of sense-perception, his use of the technical term forma evokes the scholastic distinction between form and matter. According to the scholastics, the form of a thing is what makes that thing what it is. Descartes can be read as suggesting that the 'matter' of a thought is the activity of the mind itself, while its 'form' is the idea taken objectively; the idea `informs' the mind, so that what the mind thinks is a thought—an ideasm—of the thing of which it has an ideaso. When I have a sensory experience of heat, for example, the ideao of heat informs my mind; when I have a visual sensory experience of a book, the ideao of the book informs my mind; when I think of God, the ideao of God informs my mind; and so on. What does Descartes mean, then, when he says that we have an idea? How we answer this question will depend on which sense of 'idea' is in play.

Since ideasm are acts of thought, one kind of account of what it means to say we have an idea will appeal to the intellectual act that occurs when we have that idea. Thus to say one has an idea might mean one is presented with a visual image, or a sense-perception of another kind. Or it might mean one understands something. For example, in the Third Meditation, the meditator says that he 'understands' [intelligam] what a thing, truth and thought are; these are things of which he has innate ideas (CSM II 26; AT VII 38). Likewise, when the meditator refers a few pages later to his 'idea of God,' he says, 'By the word "God" I understand [intelligo] a substance that is infinite, <eternal, immutable,> independent, supremely intelligent, supremely powerful, and which created both myself and everything else' (CSM II 31; AT VII 45). In these cases, to have an idea is to know what the thing is; it is to have a concept of the thing, which presumably means either that one can list various attributes that belong to it or that one can identify the thing under various conditions. When Descartes refers to mental operations like these, acts such as understanding or perceiving, he is most likely referring to an ideam. On the other hand, if we are referring to an ideao, then to say we have some idea is to make a claim about some object of thought. Descartes clarifies this sense of 'idea' in the First Set of Replies, saying that 'an idea is the thing which is thought of in so far as it has objective being in the intellect' (CSM II 74; AT VII 102). 'Objective being' signifies 'the object's being in the intellect in the way in which its objects are normally there' (CSM II 75; AT VII 102). For example, he says, 'the idea of the sun is the sun itself existing in the intellect—not of course formally existing, as it does in the heavens, but objectively existing, i.e. in the way in which objects normally are in the intellect' (CSM II 75; AT VII 102–103). His point is that there are two types of existence or being that an object can have. To exist formally is just to exist in the world; substances and their modes possess this sort of existence. To exist objectively, however, is to exist in an intellect. Thus a tree exists formally in my front yard; it exists objectively when I perceive it. So, to say that one has an ideao is to say that a certain object of thought is present in the mind. But must an idea ??? thought is present in the mind. But must an ideao be the object of some occurrent act of thought? In other words, can we make any sense of the notion of an ideao without there being an intellectual act in which the ideao figures—that is, without there being an ideam? More bluntly, can an ideao exist in the mind without being perceived, that is, without the thinker being explicitly aware of it?The received view is that the answer to these questions is 'no.' Chappell asserts that to say that ideasm represent ideaso is to 'suggest that the relation is necessary, at least on the side of the ideao: for it suggests that every ideao is represented by an ideao.' Later he suggests that `there is no ideao that is not joined to some one ideao by the representative relation.' Similarly, Lilli Alanen asserts that the two senses of 'idea' are 'two inseparable sides of the same phenomenon that necessarily occur together—although they can be considered apart for purposes of analysis.' I shall argue that while this may be true of Cartesian adventitious ideas, it need not be true of Cartesian innate ideas. Adventitious ideas, Descartes says in the Third Meditation, differ from innate ideas insofar as the latter seem to come only from his nature, while the former seem to come from some other source—namely, from external objects (CSM II 26; AT VII 38). It is indeed true of Cartesian adventitious ideas that the ideao is the object of some occurrent act of thought. To have an adventitious idea in the mind is to have a thought of which that idea is the object; that is, for adventitious ideas, every idea in the objective sense is

Important questions in Descartes's theories of ideas[edit]

What are the questions that Cartesian commentators still argue over? There are surprisingly many.

NOTE: For many of the following, there is the presumption of "for Descartes" added to each question.

Epistemological questions in DTOI[edit]

- Are all ideas innate?

- Does Descartes's theory of ideas offer any insights into the nature of reasoning and logical thinking?

- How does Descartes define perception and how does this concept fit within his theory of ideas?

- What is Descartes's position on awareness of all innate ideas?

- Does Descartes support an incorrigibility thesis that there are mental states about which it is impossible to be mistaken about them?

- What are the three grades of materially false ideas? Examples of the three grades from least materially false to more materially false are (A) confused non-sensory intellectual ideas of idolators about god, (B) secondary quality sensations such as those of color, taste, or warmth and coolness, (C) confused ideas of hunger and thirst such as the sensation of thirst when one has dropsy.

- How does Descartes account for erroneous ideas in his theory?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas interact with his skepticism?

- How does Descartes use his theory of ideas to justify belief in the external world?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas contribute to the cogito ("I think, therefore I am") argument?

- In Descartes's theory, what are the consequences of an idea failing to accurately represent reality?

- How does the concept of the "evil demon" interact with Descartes's theory of ideas?

- How does Descartes deal with knowing the self through ideas?

- How does the theory of ideas contribute to Descartes's understanding of truth and falsity?

- Does Descartes's theory of ideas allow for an understanding of our own ignorance or lack of knowledge?

- How does Descartes reconcile the limitations of human perception with his theory of ideas?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas account for sensory illusions or hallucinations?

- How does the concept of causality fit into Descartes's theory of ideas?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas deal with the question of personal identity?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas account for the possibility of false beliefs or self-deception?

- What is the role of the body in Descartes's theory of ideas?

- Does Descartes's theory of ideas account for the ability to form new ideas through experience?

- How does the concept of doubt factor into Descartes's theory of ideas?

- Does Descartes's theory of ideas suggest a particular epistemological method?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas distinguish between different types of knowledge (e.g., empirical, a priori)?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas handle the problem of other minds?

- What role does the concept of 'perfection' play in Descartes's theory of ideas?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas address the nature of paradoxes?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas account for shared or collective ideas?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas address the nature of contradiction or inconsistency within ideas?

- How does the concept of analogy or metaphor function in Descartes's theory of ideas?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas treat the concept of truth versus illusion?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas consider the role of emotional states in the formation and interpretation of ideas?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas handle the notion of perceptual relativity?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas address the concept of potentiality versus actuality?

Mind questions in DTOI[edit]

- What is the intellect?

- What are sensory ideas?

- What is perception?

- What is the essence of thought?

- What does it mean for all ideas to be of something?

- What makes an idea be the form of a thought?

- How does Descartes define the relationship between the form of a thought and an idea?

- How does consciousness enter into Descartes's theory of ideas?

- Are there any mental states that a mind is not immediately aware of?

- How does Descartes conceptualize the intellect in relation to his theory of ideas?

- How does Descartes articulate the essence of thought in his philosophical framework?

- How does consciousness fit within Descartes's theory of ideas?

- Does Descartes acknowledge mental states that a mind is not immediately aware of in his theory?

- What is the difference between a Cartesian thought and a Cartesian idea?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas address the phenomenon of mental images?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas account for the perception of pain and pleasure?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas deal with the concept of memory?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas account for the perception of emotion?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas handle the concept of illusion or misperception?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas account for the existence and nature of complex ideas?

- Does Descartes's theory of ideas provide any insights into the nature of creativity?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas account for the phenomenon of synesthesia?

- How does Descartes's theory of ideas relate to his understanding of reason and rationality?

- Does Descartes's theory of ideas allow for the possibility of conflicting ideas co-existing within a single mind?

- How does the concept of subjectivity versus objectivity figure into Descartes's theory of ideas?

- Does Descartes's theory of ideas offer any insights into the nature of human judgment?

Representation questions in DTOI[edit]

- How do ideas represent and what is required?

- Do all ideas represent?

- If not all ideas represent, which ones do not?

- Are there different ways that ideas can represent? Does Descartes propose different modes or mechanisms of representation in his theory of ideas?

- Are there any examples of Cartesian ideas that do not "represent"?

- What criteria does Descartes use to determine whether an idea accurately represents something?