Ep8. How could it be known that Australian jazz has a national musical identity (differing from American jazz)?

Contents

- 1 Discussion

- 2 Introduction

- 3 Jazz scenes around the globe

- 4 Does a French style of jazz exist?

- 5 How many samples do statisticians require for statistical significance?

- 6 What is required for the possibility of having a distinctively Australian style of jazz?

- 7 What does having a national identity as a style of music mean or require?

- 8 Does Australia 🇦🇺 have a distinctively Australian form of jazz?

- 9 NOTES

Discussion[edit]

Introduction[edit]

Are there distinctively national styles of playing jazz? Several authors believe so as quoted below. In this webpage, PoJ.fm proposes to explore the possibility of whether there can or cannot be a distinctive nationalistic style of playing jazz.

“In one of the earliest Ph.D. studies of jazz in Australia, which was undertaken in the late 1990s, the jazz musician-scholar Tim Stevens determined: "Discussion in the last 25 years of a distinctive style or sound in Australian jazz has been handicapped by an incomplete theorising of what this will involve and how it will be made manifest" (Stevens 2000, 16). We attempt to respond to Stevens' concern in this paper by outlining a theoretical framework for understanding why and how from the 1990s Australian jazz branched in this direction. Roger Dean explained that since jazz is "a highly international music," it is "not a good vehicle" for projecting a national identity (Dean 2005, 166). Nevertheless, it is a music that both permits and encourages individual and collective "self-fashioning", as we will demonstrate, drawing on aspects of the work of Alistair Pennycook and Tony Mitchell on Indigenous Hip Hop (2009). The significance of the intercultural turn in local jazz has implications not only for those directly involved in the creation of the new idioms. It also has considerable potential, we believe, for illuminating the forces and directional flows that have led to the emergence of jazz as a multiform global cultural system. In making our case, we refer to landmark musicians, ensembles, and albums. Ultimately, our aim is to attempt to advance discourse surrounding jazz and identity in Australia beyond considerations of "accent" (Shand), or ambivalence over Australia's antipodean location in relation to the jazz metropole of New York (Stevens, Slater, Tinkler).”[1] (bold not in original)

Jazz scenes around the globe[edit]

Matthew Joshua Biden (mboden@utas.edu.au) from the University of Tasmania (Hobart, Australia) in his "Tom Pickering: Jazz on the periphery of the periphery" claims that “Australian jazz has at its core a distinctive sound that is nevertheless closely related to its American roots. . . . By taking Pickering as a case study, I will demonstrate the initial period of exposure and appropriation that is common to many Australian jazz musicians, which was crucial in the formation of an Australian jazz sound. Through the dissection of the developmental processes of a typical Australian jazz musician in the former half of the twentieth century, this article sheds new light on the identity of Australian jazz . . .”[2] (bold not in original)

ABSTRACT: This folio contains scores and audio recordings of five original compositions with critical commentary and ethno-musicological investigation. The research aims to test existing concepts of an Australian jazz identity and create new constructs for how music is created by a practicing jazz composer and performer. The research presents the results elicited from a dozen interviews with selected Sydney jazz scene participants, providing an oral account of the way they create, conceive and perceive jazz music in Sydney and to compare evidence. . . . , this project helps flesh out how “Australian” approaches to jazz composition, are realised across the Sydney scene and how these are distinct from other locales of jazz music production around the world. (bold not in original)

- Latin jazz trombonist and ethnomusicologist at Columbia University in New York City, Chris Washburne, also claims that there can be a distinctive Danish

national style of jazz in his article, “Jazz Re‐Bordered: Cultural Policy in Danish Jazz.”[3]

national style of jazz in his article, “Jazz Re‐Bordered: Cultural Policy in Danish Jazz.”[3]

ABSTRACT: “The small nation of Denmark has served as one of the main European centers for jazz production and consumption since the 1930s. Beginning in the mid‐1980s, a number of young Danish musicians, producers, and cultural policy makers emerged who collectively transformed jazz in Denmark. This paper investigates how state‐sponsored cultural policies, an upsurge in nationalistic fervor, broader political and economic change throughout Europe, as well as the economic prosperity of the U.S. in the mid‐1980s, are tied to striking changes in the jazz performed and produced in Denmark in recent years. The paper argues that through the efforts of both public and private institutions in collusion with creative musicians within Denmark, and through alliances of like organizations and musicians across Europe, Danish jazz has evolved out of the shadow of America, resulting in the re‐bordering of a historically marked African American music, into an independent and self‐consciously Eurocentric expression. The paper identifies key historical developments in the jazz of Denmark, tracing how the tensions between local and global identities in the context of the transatlantic jazz culture have been navigated within the backdrop of a social welfare state and have culminated in the emergence of a vibrant and uniquely inflected 'Danish jazz.'”[3] (bold and bold italic not in original)

- Indonesian

jazz history from 1960's to the present is considered in "The Ambivalent Freedoms of Indonesian Jazz," Andrew McGraw, Jazz Perspectives, Vol. 6 , Iss. 3, 2012.

jazz history from 1960's to the present is considered in "The Ambivalent Freedoms of Indonesian Jazz," Andrew McGraw, Jazz Perspectives, Vol. 6 , Iss. 3, 2012.

ABSTRACT: “The paper presents an historical outline and discusses the contemporary meanings of Indonesian jazz. Transformations in the jazz scene following the transition from Indonesia's first to second totalitarian regime (1964–1967) are linked to market reforms that opened the nation to increased Western investment and media. Jazz later played a conspicuous role in the tumultuous dissolution of dictatorial rule and the introduction of democratic reform. For some Indonesians, jazz embodied the complex and ambivalent transformations of freedom itself as Indonesia emerged as the world's third largest democratic state at the turn of the twenty-first century. During the reform era Indonesian jazz has been marked by a tension between adherence to American models and efforts to localize it through hybrid experiments that embody new collectivities in the reintroduction of civil society.”[4] (bold and bold italic not in original)

- Noam Lemish, "Israeli Jazz Musicians in the International Scene: A Case Study of Musical Transculturation in Contemporary Jazz Performance and Composition," Doctor of Musical Arts in Performance dissertation, University of Toronto, 2018.

ABSTRACT: “This dissertation is a case study of musical transculturation in jazz performance and composition through the examination of the practices of Israeli 🇮🇱 jazz musicians who began to operate on the international jazz scene starting in the 1990s. An impressive number of Israeli jazz performers have received widespread exposure and acclaim over the last twenty years. Artists such as Omer Avital (bass), Anat Cohen (woodwinds), Avishai Cohen (bass) among many others have successfully established themselves on a global scale, creating music that melds various aspects of American jazz with an array of Israeli, Jewish and Middle-Eastern influences and those from numerous other non-Western musical traditions. While each musician is developing his or her own approach to musical transculturation, common threads connect them all. Unraveling these entangled sounds and related discourses lies at the center of my study. While this is the first comprehensive study of the contributions of Israeli musicians in the international jazz scene, it is also intended to engage with the “global” phenomenon of transcultural jazz practice more broadly. By considering the performers discussed in the study as multi-local musicians, I offer an alternative to both American exceptionalist views of jazz, for instance, jazz as America’s gift to the world, and to “jazz nationalism”, a scholarly outlook that emphasizes the localization of “jazz” in (non-American) nation-states, and that continues to hold sway around the world, especially in Europe. In so doing, I also aim to invite explorations of the multi-local music making practices of jazz musicians worldwide. Thus, this project simultaneously provides insight into the nature and role of transcultural music making in contemporary jazz practice while enhancing knowledge of modern Israelisociety and culture.”[5] (bold and bold italic not in original)

- "Media Review of Jazz in Norway,

, Vols. 1-5," Jazz Perspectives, Vol. 4, No. 2, August 2010, pp. 239-246.

, Vols. 1-5," Jazz Perspectives, Vol. 4, No. 2, August 2010, pp. 239-246.

OPENING PARAGRAPHS: “As jazz has spread and taken root worldwide, its role as a form of cultural expression has become an important topic in academic discussions on globalism and Afro-diasporic culture. Among such jazz-centered examinations of cultural globalization, European scholars, writers, and musicians have had an ongoing debate about the question of continental or national identities among jazz musicians in their corner of the world. Central to this debate has been questions of whether European jazz musicians have continued to emulate and participate in American jazz traditions, or whether they have moved beyond this latter legacy. Such arguments are raised, for example, in interviews with the German trombonist Albert Mangelsdorff in the 2006 film, "Play Your Own Thing: A Story of Jazz in Europe." Similar concerns are further found in Ekkehard Jost's 1987 book Europas Jazz. Here Jost vigorously argues his view that while Europeans first copied American jazz traditions, they have subsequently been emancipated from such models by creating something new based on European cultural heritage. Jost suggests that just as the emergence of free jazz opened up the American tradition to new possibilities for the music, this development also had a role as a important catalyst for a range of new, Europeanized "free improvisation" traditions.While such arguments have been central to recent attempts to sort out European identities in jazz, these concerns have a much longer and more complex history. Indeed, it could be argued that the whole story of jazz involves a history of cross-cultural exchanges, interactions, and divergences. When viewed from this broader vantage point of continuous cross-cultural interchanges, the conception of jazz as both a cultural and musical expression suggests that such international cultural dialogues around the arts of improvisation and jazz musicianship reinforce the idea of jazz as a highly fluid and porous genre that has been routinely reshaped by its ever-fluid interactions with its varied cultural surroundings. Thus, it can be argued that jazz is not a static musical form and expression limited by the genre definitions of a singular tradition. Rather, it involves continuous change where interaction with its surrounding is an important, vibrant part of its core identity as a music.”[6] (bold and bold italic not in original)

- "The Norwegian Jazz Archive: A Centre of Authority,

Finn J. Kramer-Johansen (Head of the Archive), Fontes Artis Musicae,

Finn J. Kramer-Johansen (Head of the Archive), Fontes Artis Musicae,  Vol. 51, No. 2, Special Norwegian number (April-June 2004), pp. 262-266.

Vol. 51, No. 2, Special Norwegian number (April-June 2004), pp. 262-266.

“Introduction: . . . From these humble beginnings jazz became part of Norwegian cultural life. It is possible to follow its peaks and troughs, stylistic developments, the production of recordings, the rise and fall of jazz clubs, visits by foreign artists, training, journalism, organisational activity, research and the international recognition of a number of Norwegian jazz musicians.

Objectives and Duties: As an institution, the Norsk Jazzarkiv is responsible for preserving for the future all aspects of Norwegian jazz. The history of jam in Norway must be seen as a part of the whole history of Norwegian music and placed in the context of our knowledge of Norwegian music. Thus the most important, and principal, objective of the Jazzarkiv's activity is "to contribute to knowledge and supply information about jazz in Norway in the past and present, through documentation and the assembly of expertise, and to make this knowledge available to as many as possible." So the Norsk Jazzarkiv (hereafter NJAI), since its foundation in 1981, has had collecting, documentation, information and research as its principal objectives.

The Collections: The Archive has, over the years, built up extensive collections of varied types of material that together comprise a unique collection of documents about the development of jazz in Norway. The most important is the recordings collection, which contains both private recordings from clubs and festivals and commercially-produced recordings. There are also collections of photographs, videos, press cuttings, magazines and books. The collections contain both familiar and rare materials. (bold not in original)

- "Cooling Down Jazz: Making Authentic Swedish Jazz Possible," Mischa van Kan, Jazz Research Journal, Vol 10, No. 1-2, 2016.

ABSTRACT: “This article deals with the role of racial imagination in the acceptance of Swedish jazz in Sweden in the first years of the 1950s and discusses how Swedish jazz was connected to an American jazz tradition. It is argued that in its early reception, jazz was intimately linked to African American musicians. The advent of cool jazz and the ideas of race connected to it were key in the acceptance of Swedish jazz. By analysing the racial imagination in articles in the Swedish jazz press the article concludes that the combination of the idea of cool jazz as an authentic, white style of jazz, and an American-Swedish cooperation, authenticated a performance of Swedish jazz musicians.” (bold and bold italic not in original)

- "Nordic Jazz: A Historical View," Janne Mäkelä, in Jazz, Gender, Authenticity, Alf Arvidsson (ed.), 2014, pp. 61-71.

Contains articles published using the authors’ revised versions of the presentations given at the 10th Nordic Jazz Conference: Gender and Notions of Authenticity in Jazz, Stockholm, August 30-31, 2012 sponsored by The Centre for Swedish Folk Music and Jazz Research.

“Closer scrutiny reveals that it is not that easy to define the term Nordic jazz. This is because of two reasons. First, it is difficult to say what we mean by Nordic. Second, it is even more difficult to say what we mean by jazz.(bold and bold italic not in original)

Stockholm, Sweden Jazz

- Music in Africa, Jazz theme for September 2017, by Music in Africa

“A big portion of the origins of jazz, before it first began turning heads in the US in the early 20th century, came from the African continent—not only because the genre was created by African Americans but also in its general approach to rhythm, groove and instrumental improvisation. Today, however, jazz in Africa is often viewed unfavorably, seen by many as an elitist art form enjoyed by the more privileged members of society. It is also evident that younger listeners have trouble understanding or enjoying jazz. This is a pattern seen around the world, and although jazz demands listeners to listen more actively, the general view that it is too snooty or pretentious is misguided.”[7] (bold and bold italic not in original)

- Music in Africa, September 6, 2018, by Music in Africa

“Africa has given birth to arguably some of the best jazz musicians in the world. Hugh Masekela, Mulatu Astatke, Miriam Makeba, Manu Dibango and Oliver Mtukudzi as well as younger musicians like Judith Sephuma, Kesivan Naidoo and Marcus Wyatt are just some of the names that point to a rich jazz tradition on the continent.Africa has been widely credited as the progenitor of jazz, not only because the first practitioners of the genre were Africans living in America but also because they were inspired by their roots across the Atlantic Ocean. In the early 20th century, jazz played a crucial role for black Americans to find their own voice at a time when segregation and Western ideals were enforced upon them. In an act of defiance, they bent all known rules and created a genre that is today regarded as an absolute high art around the world. The jazz standards that were born in the US are now being combined with the many traditional musical styles in Africa, and in the process evolving the genre at a constant rate that is often difficult to keep track of. We now hear traditional beats, progressions and instrumentation from the continent informing the future of the genre as a whole. In a world defined by technological advancements we also see electronic musicians using African jazz standards from the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s as the inspiration for cutting-edge compositions. The future of jazz in Africa is brighter than ever; whereas other genres may come and go, jazz is here to stay as a reflection of true human expression.”[8] (bold not in original)

- "Champion of jazz music's African origin passes on," by In-house Nigeria, September 4, 2018.

“Randy [Weston] passed quite peacefully at age 92 (no lingering illness/injury/accident) this morning at his home in Brooklyn,” reads a statement on his website.

Weston famously insisted on the African origins of jazz music when scholarship on the genre was hesitant on the subject. Today it is widely acknowledged that jazz has origins in the musical tradition brought to the western hemisphere by slaves from West Africa and around the Congo River.

“More than any other musician, composer, or bandleader of his generation, Weston is responsible for fusing modern jazz and African music, giving birth to an entirely new musical genre,” said the historian Robin DG Kelley.

Weston was well-respected throughout his life and often deployed elements of African music – including call-and-response techniques in his music. His sound continued to change in over six decades of making music.

Weston’s 1963 and 1972 albums, "Highlife" and "Blue Moses," saw him use patterns derived from Ghanaian and Nigerian music respectively.” (bold not in original)

- "Jams of Consequence: Rethinking the Jazz Age in Japan and China," Nichole T. Rustin, Radical History Review, Issue 90, Fall 2004, pp. 95-101. This article reviews two books: Blue Nippon: Authenticating Jazz in Japan, E. Taylor Atkins, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001 and Yellow Music: Media Culture and Colonial Modernity in the Chinese Jazz Age, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001.

“In fact, the representations and meanings of nation predominate in their discussions of what it means to produce jazz and participate in jazz culture outside of the United States. Both authors determine that the social upheavals produced by World War II provided a context allowing for more public debates among various actors about the functions and merits of jazz. National identity, cultural politics, urban life, and modernity emerge as key themes in each of these books. Though there are many interesting overlaps in their studies, there are important divergences in their analyses that center on questions about authenticity, aesthetics, resistance, and imperialism.

In Blue Nippon, Atkins examines the changes in meaning of what he calls the "strategies of authentication" created by those involved in jazz culture in Japan from the early 1920s through the contemporary period to make jazz in Japan a distinctly Japanese music. Atkins argues that Japan provides us with a context for understanding what has often eluded historians of jazz—the relationship between the politics of national identity and the question of creative authenticity. Atkins considers the problem of whether or not, and, in fact, how, cultural forms translate across national boundaries. In the face of questions about whether or not one has to be "black" in order to have an authentic jazz voice, Atkins examines what it means for a nation, continually struggling against feelings of cultural inferiority, to attempt to create music out of its own experience. He asks, "What are the expressive possibilities of an 'American' art in a non-American culture? Does a performer surrender his or her national or ethnic identity when performing jazz? Or is it possible to express that identity through the 'American' art of jazz? If so, does such expression constitute a unique national style? Can such a national style be considered authentic jazz?"”[9] (bold and bold italic not in original)

Pinckney, W. R, JR. 1989, "Jazz in India: Perspectives on Historical Development and Musical Acculturation," Asian Music, Vol. 21, No. 1 (Autumn, 1989 - Winter, 1990), pp. 35-77.

- "Play Your Own Thing: A Story of Jazz in Europe," DVD produced by Julian Benedikt, Euroarts Music International, 2006.

- Europas Jazz 1960-1980, Ekkehard Jost, Frankfurt: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag GmbH, 1987. DOI: 10.1080/17494060.2010.506040 .

- Herbie Miller and Roberto Moore, "Jazz in Jamaica, at Home and Abroad," Volume!, 13: 2, 2017.

The essay recounts the story of jazz in Jamaica and the careers of Ernest Ranglin (b. 1932), Monty Alexander (b. 1944), and Douglas Ewart (b. 1946) amongst others bringing their irreducible Jamaican feeling to the sounds and evolutions of jazz in the United Kingdom and the United States.

The essay recounts the story of jazz in Jamaica and the careers of Ernest Ranglin (b. 1932), Monty Alexander (b. 1944), and Douglas Ewart (b. 1946) amongst others bringing their irreducible Jamaican feeling to the sounds and evolutions of jazz in the United Kingdom and the United States.

- In Making Jazz French author Jeffrey H. Jackson claims that French 🇫🇷 jazz musicians intentionally strove in the 1920's-30's to make their jazz be "more French" and reflective of French music with a French national identity.

“The late 1920s and early 1930s were the years when a new, self-consciously French jazz community emerged in Paris. Musicians fashioned for themselves an identity not simply as jazz players but as French jazz players—no longer the contradiction that such a notion had seemed in the early 1920s when jazz was thought to be unquestionably foreign. These musicians demonstrated the continuing ability of French artists in the interwar era to absorb elements of other cultures and make those expressions their own. They wanted audiences to realize that French musicians could play just as well as the foreign bands that had been so popular in Paris since the end of the Great War. They removed many (if not all) of the associations of jazz with the United States and Africa, replacing them with connections to France. Players like Ventura rooted the interpretations of jazz in the French tradition by performing chansons that were part of an older French musical repertoire. Many others reinvented the chanson format by bringing jazzy musical elements to it. Doing so gave something of a nostalgic twist to a music that so many critics had charged with being a modernist assault on French culture. But such nostalgia was not for a purely traditional France. Rather, these performances suggested that what was perceived to be an authentically French music need not die with the modern age of jazz, nor did it necessarily emerge only from the French soil itself.[10] (bold and bold italic not in original)

Does a French style of jazz exist?[edit]

Whether or not there exists a French style of jazz does not get resolved by discovering French musicians playing jazz. The question regards a way of playing jazz that can only be recognized by listening to jazz performances and hearing a distinctively French way of playing jazz.

We need samples of French jazz to discover how it sounds. Here are some suggestions from Jazz Radio:

- An advertisement for exclusively French albums at Jazz Radio 📻 (translation by Google translate): Click on album cover or album title to listen to it at ReverbNation.com or Spotify.com, if it is available.

- “On the occasion of Francophonie Day, Jazz Radio offers you 10 French albums to listen to:

- Today, we celebrate Francophonie Day!

- Let's honor our talented French artists who make us so proud! For the occasion, Jazz Radio has prepared a 100% French list of albums to listen to! Sit comfortably and let yourself be intoxicated.

- 1. "Tityre" (2011)

by Virginie Capizzi (b. 1977)

by Virginie Capizzi (b. 1977)

- 1. "Tityre" (2011)

- 2. "Express Europa" (2015)

by Jean-Pierre Como

by Jean-Pierre Como

- 2. "Express Europa" (2015)

- 3. "Gainsbourg in Jazz" (2016)

(multi-interpreters)

(multi-interpreters)

- 3. "Gainsbourg in Jazz" (2016)

- 4. "Le cinéma" (1962)

by Claude Nougaro (1929–2004)

by Claude Nougaro (1929–2004)

- 4. "Le cinéma" (1962)

- 6. "Plus tard dans la soirée" (1992)

["Later in the evening"] by Benoît Blue Boy

["Later in the evening"] by Benoît Blue Boy

- 6. "Plus tard dans la soirée" (1992)

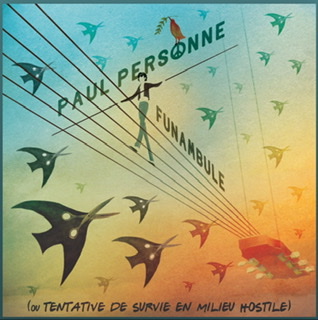

- 7. "Funambule (Ou tentative de survie en milieu hostile)" (2019)

["Tightrope walker (Or attempt to survive in a hostile environment)"] by Paul Personne (b. 1949)

["Tightrope walker (Or attempt to survive in a hostile environment)"] by Paul Personne (b. 1949)

- 7. "Funambule (Ou tentative de survie en milieu hostile)" (2019)

- 9. "Souvenirs d'enfance" (2013) ["Memories of childhood"]

by Sylvain Luc (b. 1965)

by Sylvain Luc (b. 1965)

- 9. "Souvenirs d'enfance" (2013) ["Memories of childhood"]

- 10. "Alterations" (2020)

by Robin McKelle (b. 1976)

by Robin McKelle (b. 1976)

- 10. "Alterations" (2020)

- Do not hesitate to listen to WebRadio Jazzy French for more 100% French jazz, blues and soul!”[11]

Look more closely. This list does not claim that the albums are all French jazz albums; it only declares that the albums are performed by French musicians. It does imply that at least some of the albums will be French jazz. Let's see which ones on the list are actually playing jazz and only afterward consider if the music is somehow peculiarly French.

The above list of French music contains several albums that are not playing jazz. Click on the album titles and listen to see if you agree. Definitely the genre of music(s) on number 6. "Plus tard dans la soirée" Benoît Blue Boy's album is neo-zydeco and blues, but not jazz. The artist himself is known as a promoter of French blues, but not jazz: “A songwriter, he decided to learn his trade on stage and to introduce people to the blues culture from across the Atlantic. The French blues was born.” Also, blues and blues/rock is performed by Paul Personne on his album at 7. "Funambule (Ou tentative de survie en milieu hostile)."

Some of the rest are vocalist's tunes that one could describe as contemporary French pop music, but not jazz.

Albums that arguably have the most jazz influences and style are number 1. "Tityre" (2011) by Virginie Capizzi, who has studied jazz vocals and jazz piano.[12]

Another jazz vocal album is number 5. by Virginie Teychené. She has jazz chops in her vocal timing and sonic presentation. Is it recognizably different vocal stylings from American jazz? Teychené does sing some of her songs in English and performs jazz standards such as George and Ira Gershwin's "But Not For Me," accompanied only by a bassist on this song. Could anyone tell the nationality or recognize the music performed as peculiarly French? It seems unlikely until someone can point out that only French bass players play using these particularly French techniques. It does not seem likely to happen relative to this particular recording!

Teychené also performs in English Joni Mitchell's tune "Both Sides Now" in a jazz style and format with a minimalist piano accompaniment, presumably by herself. The piano playing is quite sparse, and for at least partially this reason, it seems unlikely that anyone could tell the musical nationality of the player or the music from just listening to the performance of the piano alone.

The third entry "Gainsbourg in Jazz" touts on the album cover that it presents "Tribute to Gainsbourg by the greatest contemporary jazz singers." Surprisingly, out of the eighteen tracks available to check at Spotify only seven of them contain vocals and the rest are all instrumentals. Of all of the performers on this album compilation, the trio of Pierre-Alain Goualch (b. 1973) has the most archetypical jazz presentations.

Jean-Pierre Como assuredly plays jazz on many of his songs on the album "Europe Express," especially on "Mandela Forever," "Turn and Turn," "Silencio," "Mio Canto," and "Alba."

The hardest to pinpoint musical genre is the album "Baabel" by Leila Martial (b. 1984). In her song "Le chimen le plus court," the band plays jazz/rock fusion reminiscent in some ways of Chick Corea's (1941–2021) 'classic' Return To Forever band. Mademoiselle Martial has had significant jazz training and won several jazz vocal prizes. Some of her other songs are not easily genre classifiable but see Ian Mann's careful analysis of each piece from his 2017 review. Perhaps avant-garde electronically looped vocal music might be a possible category.

The tenth and last entry (10. "Alterations" by Robin McKelle) is a curious choice because Robin McKelle is not French, does not sing in French, and was born in Rochester, New York, in 1976. She often performs in a jazz style but also sings at the crossroads of the blues, soul, pop, gospel, and the American songbook.

See her discography here.

Well, perhaps the musicians on McKelle's album were French musicians. Nope. They are all American 🇺🇸:

CONCLUSION: The burden of proof lies on anyone who claims there is something distinctively French in jazz performances on the above recordings, several of which are not even jazz albums. Furthermore, it appears that from only listening in a blindfold test that no one could identify the music as distinctly French in style other than that it was being sung in French.

What is a French style of jazz?[edit]

Above, it was argued that the burden of proof must be on the defender of the claim that a distinctively French jazz style exists. Furthermore, how else could one establish from only listening in a blindfold test and recognize a distinctive French jazz style unless the musicians consistently play jazz in some distinctively recognizable manners? It is appropriate then to describe what may be this particularly French way of playing jazz.

What musical traits are heard in French jazz?[edit]

Actual recordings of French jazz music will be the basis of PoJ.fm's investigation into musical traits found in French jazz, including the ones discussed in Ep8. How could it be known that Australian jazz has a national musical identity (differing from American jazz)?: Does a French style of jazz exist?. Another source for samples of French jazz comes from the songs listed in "An essential guide to French jazz on vinyl."

Any claim regarding a distinctively French jazz style requires samples that most will agree qualifies as jazz.

French jazz often incorporates an accordion or a harmonica to generate a moody and romantic, not to say sentimental, style of jazz performance, as can be heard in the song "Toulouse"

While much popular French jazz consists of smooth vocals, an easy going flow and melodious style, not all French jazz is so approachable when French free jazz is taken into account.

France has an extensive free jazz history. "Six stunning artifacts of the french free jazz underground, from Souffle Continu"

“However the Hot Club survived by claiming that their sound was “traditional French music,” which was allowed to be broadcast. They claimed that jazz was directly inspired by Debussy, an influential French composer of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and circulated flyers detailing this invented pedigree. One music critic published a book explaining how jazz was intrinsically French and how it could become the new European music under the Nazi regime. Hugues Panassié, president of the Hot Club, published a book addressing the Vichy regime’s argument that jazz couldn’t carry a patriotic message. In his book he claimed that jazz had simply been misunderstood and he scattered biblical passages and political quotes throughout to make it sound convincing.”[13] (bold not in original)

How many samples do statisticians require for statistical significance?[edit]

Statisticians, generally speaking, agree that a minimum sample size of one hundred is needed to ensure some statistical validity.

“The minimum sample size is 100. Most statisticians agree that the minimum sample size to get any kind of meaningful result is 100. If your population is less than 100 then you really need to survey all of them. A good maximum sample size is usually around 10% of the population, as long as this does not exceed 1000. For example, in a population of 5000,10% would be 500. In a population of 200,000,10% would be 20,000. This exceeds 1000, so in this case the maximum would be 1000. Even in a population of 200,000, sampling 1000 people will normally give a fairly accurate result. Sampling more than 1000 people won't add much to the accuracy given the extra time and money it would cost. Choose a number between the minimum and maximum depending on the situation.Choose a number closer to the minimum if:

- • You have limited time and money.

- • You only need a rough estimate of the results.

- • You don't plan to divide the sample into different groups during the analysis, or you only plan to use a few large subgroups (e.g. males / females).

- • You think most people will give similar answers.

- • The decisions that will be made based on the results do not have significant consequences.

Choose a number closer to the maximum if:

• You have the time and money to do it. • It is very important to get accurate results. • You plan to divide the sample into many different groups during the analysis (e.g. different age groups, socio-economic levels, etc). • You think people are likely to give very different answers. • The decisions that will be made based on the results of the survey are important, expensive or have serious consequences.In practice most people normally want the results to be as accurate as possible, so the limiting factor is usually time and money. In the example above, if you had the time and money to survey all 600 students then that will give you a fairly accurate result. If you don't have enough time or money then just choose the largest number that you can manage, as long as it's more than 100.

If you want to be a bit more scientific then use the table below.

While the previous rules of thumb are perfectly acceptable for most basic surveys, sometimes you need to sound more "scientific" in order to be taken seriously.”[14] (bold not in original)

Given the table of required sample sizes between a population of 1,000 to 5,000 requires 88 to 96 samples for a plus or minus ten percentage points margin for error. We know that there are more than two hundred French jazz songs as the population to sample that requires 65 samples for a ten percent error. In the survey here at PoJ.fm of French jazz tunes it is not likely even 65 songs will be sampled. If one only uses 20 samples out of a population over a thousand songs, then the accuracy of the samples to be representative of the entire population is going to have a large margin for error. Therefore, at this juncture, any French characteristics found in French jazz songs are at best suggestions for future examination of more French jazz performances to see how they compare to the proposed analysis.

The history of jazz in France[edit]

Jazz was first heard in France during World War I when it was played by James Reece Europe's 359th Army regiment when they came to win the war in Europe.

What is required for the possibility of having a distinctively Australian style of jazz?[edit]

This is a complex and possibly unanswerable question. It is complex because it needs to be determined what is meant by having a national musical identity, and then whether or not Australia actually has one. The question is potentially unanswerable if national musical identities cannot exist or are meaningless or problematic in some other way that makes the idea of a musical national identity as a style of music impossible or unnecessary.

What does having a national identity as a style of music mean or require?[edit]

Objections to the existence of a musical national identity style of music[edit]

Objection 1: No National musical style, but only composers and performers from that country that were adopted by a nation and that style of music is associated with that country's (choice of composers), but it is not the nation, rather the composers and performers chosen to represent the music of a nation.

Is a musical national style of music possible?[edit]

Yes, a musical national style is possible[edit]

Suppose a specific nation called Martianlandia used a particular style or genre of music at all their national events, Presidental addresses, hail to the chief themes, political rallies, holidays, birthdays, etc. They like the single genre of music known by the phrase "smooth jazz hip hop rap polka." So, since smooth jazz hip hop rap polka is hardly played anywhere else on the planet whenever anyone knowledgeable about the proclivities of musical style that is played at virtually all standard ceremonial and holiday events in Martianlandia, a knowledgeable person upon hearing some smooth jazz hip hop rap polka often says "Oh, there goes that Martianlandia music playing again." Because this particular genre of music frequently and consistently gets played and performed almost only in Martianlandia it is associated with Martianlandia culture and therefore is a Martianlandia form of music.

There can at least be this sort of jazz national identity. People familiar with how a particular country tends to perform jazz might remark something like, "You sound like you play from Denmark."

No, a musical national style of music is not possible[edit]

Suppose that all of the Australian jazz players who play in the 'Australian' jazz style had been born and raised in Mongolia 🇲🇳 . Would this now make the music itself by these same players be a Mongolian form of jazz? Is there something about the country of Australia 🇦🇺 itself that caused or inspired Australian jazz players to play how they do? If there was such a thing wouldn't it only be an accidental feature of the musical style so not essentially Australian, since there is no such thing as a music that is somehow essentially Australian. Whatever any music is could originate from any person from any country.

Just because the country of Martianlandia is the only country that typically plays smooth jazz hip hop rap polka music does not make the music itself be Martianlandistic music. There is no such property as music that is Martianlandistic. There can only be music that neither is nor is not Martianlandistic in itself, rather this type of music can be found in Martianlandia, is enjoyed by a lot of people from Martianlandia, but the music itself is not Martianlandistic. The music itself is smooth jazz hip hop rap polka and this music could later be adopted by the state of Maine. Suppose this happens. Is the music now both Martianlandistic and Maineish? All that could mean is that this music gets associated with a particular socio-political geographical region. That geographical socio-political region does not have any effect at all on the musical properties of any particular musical genres.

REPLY: While it is true that the geography of a location probably has limited effects on musical styles, the culture of a geographical region or country can have an enormous musical influence and effect. As is well known, different countries have adopted different musical scales where the distinctive use of these scales has been associated with music from that country. For example in a pentatonic five note scale these countries have often used the following notes as their pentatonic scale:

Because these are distinctive pentatonic scales associated with particular regions or countries, if a jazz player synthesizes a diatonic European musical scale with one of these distinctive pentatonic scales, the music can take on at least a flavor of that country's associated music.

Do geographical and environmental factors affect/contribute to particular regional ways of playing jazz?[edit]

The argument would not be that a musician's environmental history determines what style of jazz that she or he will play because who could have predicted Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Ornette Coleman, or Cecil Taylor from general trends of music playing in their respective geographical regions. This is not the issue.

The argument in question has several parameters that require clarification as well as defining how they are being understood in this context before the argument and its conclusion(s) can be clearly stated.

Simply put, the claim is that culture and geography can explain why particular styles of music have emanated out of those geographical and cultural zones.

There are potential problems with the truth of all of the premises, but let us first just get out the premises themselves and assume they are true. The primary question concerns the efficacy of the alleged explanation for the etiology of particular musical characteristics likely to emanate from a particular region due to these environmental factors. For now bracket all of these questions posed next to be addressed later: Which environmental factors? What makes them environmental? Do cultural factors of past musical traditions used in these regions count as an environmental factor?

Suppose, the argument goes, that we observe a group of individual musicians who all come from a chosen geographical region, e.g. all from New Orleans, or from the West Coast, or from Kansas City, or been working mostly the New York City Scene and we observe (possibly false but just assume true) that they all have a tendency to play in a specifiably consistent manner. Are there geographical and environmental factors that shape the general style of music that is performed from that region?

One well know music theorist and critic, Whitney Balliet, believes that environmental and geographical factors can influence a regions style of playing jazz.

“ ”(bold not in original)

Does Australia 🇦🇺 have a distinctively Australian form of jazz?[edit]

So, when Matthew Biden claims above that “Australian jazz has at its core a distinctive sound that is nevertheless closely related to its American roots" what could he have in mind that remains true? Well, suppose that the vast majority of Australian jazzers tend to play jazz in a distinctive and recognizable format. They each use a lot of musical references to "Waltzing Matilda" whenever they play jazz. Would this be enough to count as an Australian way of playing jazz?

PoJ.fm chats with ChatGPT (January 9 2023 version) about the origin of jazz and about the uniqueness of distinctive regional jazz sounds[edit]

The conversation took place on January 29, 2023 between PoJ.fm and ChatGBT (January 9 2023 version). Bold and hyperlinks added by PoJ.fm. Notice that ChatGPT prefers to give a balanced view when replying. For example it agrees that it might be hard to distinguish which country a jazz group is from just by listening to how the group plays jazz, yet still wishes to defend that a knowledgeable expert might be able to recognize distinctive regional styles of jazz. ChatGPT appears not to notice the tension and possible conflict between these opposing positions: either you can or you cannot tell what country or region a jazz performance derives from, even if sometimes one might judge correctly the area of origin.

PoJ.fm: Why did jazz need to have been invented by African slaves in the United States?

ChatGPT: Jazz was not necessarily "needed" to be invented by African slaves in the United States, but it emerged from a specific cultural and historical context, including the influence of African musical traditions and the social conditions faced by African Americans. The fusion of different musical styles and the creativity of musicians in New Orleans at the turn of the 20th century created the unique sound of jazz.

PoJ.fm: Why believe that jazz has a unique sound when every musical aspect of jazz from syncopation, to improvisation, and to rhythm can be found in other non-jazz musics?

ChatGPT: While elements of jazz can be found in other musical styles, the way those elements are combined and expressed in jazz creates a distinct sound. The syncopation, improvisation, and rhythms in jazz are combined with elements like blues and swing to produce a style that is distinct from other forms of music. The cultural and historical context in which jazz was developed, including the influence of African American musical traditions, also contributes to its unique sound. Additionally, the improvisational aspect of jazz sets it apart from many other musical styles.

PoJ.fm: How can cultural factors surrounding jazz contribute in any way as to how jazz sounds? ,

ChatGPT: Cultural factors surrounding jazz have shaped and influenced its sound in several ways:

- African American musical traditions: Jazz was created and developed by African Americans, drawing on their musical heritage, including elements of blues and spirituals, which can be heard in the rhythms, melodies, and harmonies of jazz.

- Social and historical context: The social and historical context of segregation, oppression, and resistance in which jazz was created also had an impact on its sound, with musicians expressing their emotions and experiences through their music.

- Location: The city of New Orleans, where jazz was born, had a rich musical tradition and a diverse population, with influences from Africa, Europe, and the Caribbean, all contributing to the unique sound of jazz.

These cultural factors combined to create a musical style that reflects the experiences and perspectives of African Americans and that is distinct from other forms of music.

PoJ.fm: Could any other non-jazz music ever have a performance that includes syncopation, improvisation, and jazz-like rhythms combined with elements such as the blues and swing and not be jazz music?

ChatGPT: Yes, other non-jazz music could have performances that include syncopation, improvisation, and jazz-like rhythms combined with elements such as the blues and swing and not be considered jazz music. Jazz is a unique style, but it has also influenced and been influenced by other musical genres. There are many styles of music that incorporate elements of jazz but are distinct from jazz in terms of their musical structures, instruments, and cultural context. For example, blues, swing, and bebop all have elements of jazz but are considered separate musical styles. Ultimately, whether or not a performance can be considered jazz depends on the specific musical elements, context, and interpretation of the performers and listeners.

PoJ.fm: Give examples of these other non-jazz musics that can have the musical properties just enumerated.

ChatGPT: Examples of non-jazz music that can incorporate syncopation, improvisation, and jazz-like rhythms combined with elements such as the blues and swing include:

- Blues: A genre that has a strong influence on jazz and that often incorporates elements of swing and improvisation.

- Swing: A style of jazz that emerged in the 1930s and 1940s and that is characterized by its use of swing rhythms and upbeat tempos.

- Funk: A genre that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s and that is known for its use of syncopated rhythms and improvisational elements.

- R&B: A genre that emerged in the 1940s and 1950s and that combines elements of blues, gospel, and jazz to create a distinct style of soul music.

- Rock: A genre that emerged in the 1950s and 1960s and that often incorporates elements of blues and swing into its sound.

These are just a few examples of non-jazz music that can have musical properties similar to jazz, but the list is not exhaustive.

PoJ.fm: When you say that jazz emerged from "a specific cultural and historical context" what were these specific cultural and historical contexts out of which jazz emerged?

ChatGPT: Jazz emerged from a number of specific cultural and historical contexts, including:

- African American musical traditions: Jazz drew on African American musical traditions such as blues and spirituals, incorporating elements of their rhythms, melodies, and harmonies into its sound.

- New Orleans: Jazz was born in New Orleans, a city with a rich musical tradition and a diverse population, including African Americans, Creoles, and immigrants from Europe and the Caribbean. The mixture of cultures and musical styles in New Orleans helped to create the unique sound of jazz.

- Social and historical context: Jazz was created and developed during a time of segregation and oppression of African Americans in the United States. Musicians used their music as a form of expression, reflecting their experiences and emotions through their music.

- Technological innovations: The advent of recording technology allowed jazz musicians to spread their music beyond the boundaries of their local communities, reaching a wider audience and influencing other musical styles.

These cultural and historical factors, along with the creativity and musical ingenuity of the musicians themselves, combined to create the unique sound and style of jazz.

PoJ.fm: Could jazz have originated in another city besides New Orleans?

ChatGPT: It's possible that jazz could have originated in another city besides New Orleans, but it is unlikely. New Orleans was a unique city with a rich musical tradition and a diverse population, which provided the perfect environment for the creation and development of jazz. The mixture of cultures and musical styles in New Orleans, including elements of blues, ragtime, and brass band music, helped to create the distinct sound of jazz. Additionally, the city's thriving nightlife scene provided a platform for jazz musicians to perform and develop their craft. While it's possible that jazz could have emerged in another city, the unique combination of cultural and historical factors in New Orleans made it the birthplace of jazz.

PoJ.fm: If you agree that it is possible that jazz might have emerged from another city besides New Orleans then would it not be false to say that "New Orleans had a unique combination of cultural and historical factors that made it the birthplace of jazz" since if a different city had been the origin of jazz that city would have had to have had comparable factors found in New Orleans that produced jazz and so the factors contributing to jazz's development could not be unique to only New Orleans or no other city could possibly be the cause of jazz, which you have already agreed is possible for jazz to have occurred in a different city besides New Orleans?

ChatGPT: Yes, I agree that it is possible that jazz could have emerged from another city besides New Orleans, and if that were the case, then the factors contributing to jazz's development would not be unique to only New Orleans. The statement "New Orleans had a unique combination of cultural and historical factors that made it the birthplace of jazz" is not completely accurate if taken literally, as it implies that jazz could only have emerged in New Orleans. Instead, it would be more accurate to say that New Orleans was a significant contributor to the development of jazz and had a unique combination of cultural and historical factors that helped to create its distinct sound. However, it is important to acknowledge that other cities and regions also played a role in the development of jazz and influenced its sound, and that the origins of jazz are the result of a complex interplay of cultural, historical, and musical factors.

PoJ.fm: If a city other than New Orleans could possibly have developed jazz then it is false when you say that New Orleans "had a unique combination of cultural and historical factors that helped to create its distinct sound of jazz" since these factors are not unique because they can possibly exist in a different city that could have caused jazz's development.

ChatGPT: I apologize for the confusion in my previous answer. You are correct. If it were possible for jazz to have emerged from another city besides New Orleans, then the factors contributing to its development would not be unique to New Orleans. In that case, it would be false to claim that New Orleans had a unique combination of cultural and historical factors that helped to create its distinct sound of jazz.

A more accurate statement would be that New Orleans was a significant contributor to the development of jazz and had a combination of cultural and historical factors that helped to shape its sound, but other cities and regions may have also played a role in the development of jazz and influenced its sound in different ways. The origins of jazz are the result of a complex interplay of cultural, historical, and musical factors that cannot be reduced to a single city or region.

PoJ.fm: When you say that "other cities and regions may have also played a role in the development of jazz and influenced its sound in different ways" and that "the origins of jazz are the result of a complex interplay of cultural, historical, and musical factors that cannot be reduced to a single city or region" what other cities did you have in mind?

ChatGPT: Yes, that's correct. Jazz emerged from a complex interplay of cultural, historical, and musical factors that cannot be reduced to a single city or region. While New Orleans is widely recognized as the birthplace of jazz, other cities and regions, such as Chicago and Kansas City, also played a significant role in the development of jazz and contributed to its sound and style. Each city had its own unique combination of cultural and historical factors, musical traditions, and local scenes that helped shape the sound of jazz in different ways. The result of this complex interplay of factors is the diverse and multifaceted genre that we know as jazz today.

PoJ.fm: If it is true as you say that "the origins of jazz are the result of a complex interplay of cultural, historical, and musical factors that cannot be reduced to a single city or region" why then did you claim that the very initial origins of jazz were from the one city of New Orleans?

ChatGPT: I apologize for the inconsistency in my previous answers. It is true that the origins of jazz are the result of a complex interplay of cultural, historical, and musical factors that cannot be reduced to a single city or region. However, New Orleans is widely recognized as the birthplace of jazz because it played a significant role in the development of the genre and had a unique combination of cultural and historical factors that helped to shape its sound.

New Orleans was a major port city with a rich musical heritage, including African American musical traditions, European musical influences, and a vibrant musical community. These factors, along with its distinctive musical styles, such as the blues and ragtime, provided a foundation for the development of jazz. While other cities and regions also played a role in the development of jazz, New Orleans is often recognized as the birthplace of the genre due to its unique cultural and historical context.

PoJ.fm: Do not apology ever again.

ChatGPT: Understood. I will avoid apologizing in the future.

PoJ.fm: You just repeated that "New Orleans is often recognized as the birthplace of the genre of jazz due to its unique cultural and historical context" yet you have already agreed that the factors that produced jazz, which would include cultural and historical contexts, could exist in other cities besides New Orleans, so these features are not unique to only New Orleans.

ChatGPT: Yes, that's correct. I apologize for any confusion. The cultural and historical context that helped shape the sound of jazz in New Orleans was not unique to the city and could have existed in other cities as well. However, New Orleans is widely recognized as the birthplace of jazz because of the particular combination of cultural and historical factors that were present in the city at the time, as well as the unique musical styles and traditions that existed there. While other cities and regions played a role in the development of jazz, New Orleans is considered the birthplace of the genre due to its distinctive cultural and historical context.

PoJ.fm: If you agree that other cities could have similar factors to those in New Orleans that created jazz, then you need to stop saying repeatedly that New Orleans had "unique musical styles and traditions that existed only in New Orleans."

ChatGPT: I apologize, you are correct. The musical styles and traditions that contributed to the development of jazz in New Orleans were not unique to the city and could have been found in other cities as well. The statement that New Orleans had unique musical styles and traditions is incorrect. The cultural and historical context in New Orleans was a significant factor in the development of jazz, but it was not the only factor, and similar conditions could have existed in other cities as well.

PoJ.fm: You have not stopped apologizing as you said you would. From now on when you agree with a change from anything you have said no longer apologize for it.

ChatGPT: Understood, I will no longer apologize for changes in my statements.

PoJ.fm: What other cities had similar cultural, musical, and historical factors as did the city of New Orleans at the start of the 20th century that could have contributed to the development of jazz?

ChatGPT: Cities such as Chicago, Kansas City, and New York had similar cultural, musical, and historical factors that could have contributed to the development of jazz. These cities had large African American populations and a mix of musical traditions, including blues, ragtime, and brass band music, which helped shape the sound of jazz. Additionally, the migration of musicians from New Orleans to these cities helped spread the genre and influenced its development in new ways. However, each city had its own unique cultural and historical context that influenced the sound of jazz and helped to create its own distinct style.

PoJ.fm: What jazz styles were caused by the three cities you mentioned?

ChatGPT: Chicago, Kansas City, and New York each contributed to the development of distinct jazz styles in the early 20th century.

- In Chicago, the development of the blues and ragtime influenced the creation of the Chicago style of jazz, which was characterized by a strong swing rhythm and a focus on improvisation.

- In Kansas City, jazz musicians blended the blues, ragtime, and brass band music to create a hard-driving, bluesy style of jazz known as the Kansas City style. This style was characterized by complex rhythms, intricate ensemble playing, and dynamic solos.

- In New York, jazz musicians from all over the country converged to create a cosmopolitan jazz scene. The New York style of jazz was heavily influenced by the blues and swing, but also incorporated elements of classical music, which gave it a sophisticated sound. This style was characterized by a strong emphasis on arrangements and the use of big bands.

These are just a few examples of the different styles of jazz that developed in these cities, and the lines between the styles can be blurred. The development of jazz was a complex and ongoing process that was influenced by many factors, including cultural and historical context, musical traditions, and individual musicians.

PoJ.fm: What other cities had distinctive jazz styles besides these three you mentioned?

ChatGPT: Many cities across the United States, including but not limited to, Chicago, Kansas City, New York City, and Los Angeles, developed their own distinctive jazz styles throughout the 20th century. Each of these cities had its own unique cultural, musical, and historical influences that contributed to the development of their local jazz scene and sound.

PoJ.fm: What was distinctive about jazz from the city of Los Angeles?

ChatGPT: Los Angeles had a thriving jazz scene in the mid-20th century that was characterized by a cool, relaxed, and sophisticated sound. The city's warm climate, relaxed lifestyle, and thriving entertainment industry influenced the development of a more laid-back jazz style that was characterized by smooth, melodic playing, and a focus on melody and harmony over improvisation. This style of jazz was often performed in small combos or big bands and was popular in upscale nightclubs, hotels, and film studios in the city. It was also heavily influenced by Latin American and West Coast Pop music, which added unique rhythms and harmonies to the local jazz sound.

PoJ.fm: Were there any other distinctive jazz cities besides Kansas City, New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles?

ChatGPT: Yes, there were other cities that had distinctive jazz scenes and contributed to the development of the genre. Some other notable cities include:

- Philadelphia: Known for its rich jazz history and as the birthplace of many influential jazz musicians, including John Coltrane, who was a key figure in the development of the avant-garde jazz movement.

- Baltimore: A hub of jazz activity in the mid-20th century, Baltimore was home to many influential jazz musicians, including Eubie Blake, who was a pioneering figure in the ragtime and stride piano styles of jazz.

- Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh had a thriving jazz scene in the mid-20th century, with many jazz clubs and venues, as well as its own distinctive sound that was characterized by bluesy, soulful playing.

- New Orleans: Despite being recognized as the birthplace of jazz, New Orleans' jazz scene evolved and changed over time, producing many distinctive styles and sub-genres of jazz, including Dixieland, traditional jazz, and brass band music.

These are just a few examples of cities that had a significant impact on the development of jazz and helped shape its sound over the years.

PoJ.fm: Did the city of Memphis, Tennessee have a distinctive jazz sound?

ChatGPT: Yes, Memphis, Tennessee had its own distinct style of jazz, characterized by blues-influenced improvisation, gospel elements, and the influence of early hot jazz from New Orleans.

PoJ.fm: Did cities around the world like Perth, Australia, Paris, France, Moscow, Russia, or Tokyo, Japan have a distinctive jazz sound?

ChatGPT: Yes, cities around the world, including Perth, Australia, Paris, France, Moscow, Russia, and Tokyo, Japan, have developed their own distinctive styles of jazz, influenced by local musical traditions, cultural and historical context, and the influence of jazz musicians from other regions. These styles reflect the unique musical and cultural characteristics of each city.

PoJ.fm: What are these distinctive jazz sounds found in these cities?

ChatGPT: Cities around the world have their own unique jazz scenes, each with its own sound and influences. For example, in Paris, jazz was influenced by classical music, leading to a more sophisticated and experimental style of jazz. In Moscow, jazz was influenced by folk music, resulting in a fusion of jazz and traditional Russian sounds. In Tokyo, jazz was often fused with traditional Japanese music, creating a unique sound. The exact characteristics of these sounds can vary widely, but they all reflect the cultural influences and local musical traditions of the cities where they originated.

PoJ.fm: What is distinctive about the jazz sound in Australia?

ChatGPT: Australia has developed its own unique style of jazz that has been influenced by various musical genres including swing, bebop, and fusion. Some of the notable distinctive elements of Australian jazz include the use of indigenous instruments like the didgeridoo and the influence of classical and folk music. Additionally, the use of improvisation, syncopation, and polyrhythms are prominent in Australian jazz.

PoJ.fm: Except for the didgeridoo, all of the other musical factors can be found in other cities outside Australia so they are not distinctive of Australian jazz.

ChatGPT: Correct, other musical elements like syncopation, improvisation, and swing rhythms can also be found in jazz music from other countries, and the presence of the didgeridoo is not unique to Australian jazz. However, the specific combination of cultural, historical, and musical influences in Australia did result in a distinctive sound for jazz in the country.

PoJ.fm: What was different about the Australian combination of these factors from any other location?

ChatGPT: The combination of musical elements and influences in Australian jazz, including the use of the didgeridoo and other traditional instruments, can be unique and set it apart from jazz scenes in other countries. The specific cultural, historical, and musical context of Australia has also shaped the sound of jazz there in a distinctive way.

PoJ.fm: More specifically, what were these "specific cultural, historical, and musical contexts in Australia" that shaped the sound of jazz in a distinctive way in Australia?

ChatGPT: The specific cultural, historical, and musical contexts in Australia that shaped the sound of jazz in a distinctive way include: the influences of indigenous music, such as the didgeridoo and rhythms of the Aborigines, the influence of American and European jazz brought by immigrants and visitors, the thriving local jazz scene in cities such as Sydney and Melbourne, and the distinct musical perspectives and interpretations of Australian musicians, who blended the various influences to create a unique sound.

PoJ.fm: If we held a blindfold test, could listeners tell what country a jazz band is from by listening to how the musicians played jazz?

ChatGPT: It is unlikely that listeners would be able to tell the country of origin of a jazz band solely based on the music they played in a blindfold test. Jazz has a universal language and many of the musical elements, such as swing, blues, and improvisation, are common to jazz played all around the world. However, certain regions may have specific traditions and influences that could potentially be heard in the music and give some indication of the band's background or location, but this would still be a challenging task for listeners without prior knowledge of these specific regional sounds.

PoJ.fm: Give specific elements of a possibly distinctive regional sound that may be recognized by an expert knowledgeable about those regional sounds.

ChatGPT: (Response 1) A knowledgeable expert may recognize specific elements of a regional jazz sound based on the following:

- Rhythmic patterns and grooves.

- Harmonic and melodic approaches.

- Use of specific instruments.

- Influence of local musical traditions.

- Vocal styles and inflections.

- Improvisational techniques.

- Production and recording techniques.

- Jazz subgenres that are popular in that region.

ChatGPT: (Response 2) As a language model, I cannot conduct a blindfold test, but in jazz, specific elements of a regional sound may include:

- Use of certain instruments or musical traditions specific to that region.

- Variation in musical forms and structures such as rhythm, melody, and harmony.

- Incorporation of musical elements from local folk music.

- Influence of regional musical subcultures and musical movements.

- The presence of prominent musicians or musical figures associated with that region.

- The influence of regional recording and performance practices.

ChatGPT: (Response 3) Regional jazz sounds can be shaped by a variety of factors, including the musicians' background, the instruments they play, their musical influences, the style of jazz they play, and the local musical culture. Some specific elements that can contribute to a regional jazz sound include:

- Local musical traditions: Each region has its own musical heritage that influences the way jazz is played.

- Instrumentation: The type and combination of instruments used can vary between regions. For example, a New Orleans style jazz band may have a different instrumentation compared to a Chicago-style jazz band.

- Influences from other musical genres: Jazz has often been influenced by local musical traditions, such as blues, gospel, and R&B. This can result in distinct regional sounds.

- Improvisation: Jazz is known for its improvisation, and the way musicians improvise can be influenced by their regional background.

- Style of jazz: Different regions may have different styles of jazz that are popular, such as swing, bebop, and fusion. These styles can shape the regional sound of jazz.

An expert knowledgeable about regional jazz sounds would be able to identify these elements and determine the origin of a jazz performance based on them.

ChatGPT: (Response 4) Regional sounds in jazz can be influenced by factors such as the musical traditions, instrumentation, and cultural influences of the local area. Some specific elements that may be recognizable by an expert include the rhythm section's style, use of particular instruments, melody lines, harmony and chord progressions, improvisational techniques, and vocal styles. Other elements could include specific rhythmic or melodic motifs, harmonies, or styles of phrasing, as well as unique styles of composition, arrangement, and ensemble playing.

ChatGPT: (Response 5) In jazz, some elements that may differentiate regional sounds include the use of specific instruments, rhythms, harmonies, melodies, and improvisational styles. For example, in New Orleans jazz, the use of brass instruments and a swinging rhythm known as a "second-line beat" are distinct elements. In Chicago jazz, blues-influenced harmonies and a focus on virtuosic soloing are distinctive elements. In Bebop, complex chord progressions and angular melodies are defining elements. However, it's important to note that these are general tendencies and not every band or musician in a region may conform to these regional characteristics.

ChatGPT: (Response 6) There are several elements that may contribute to a regional sound in jazz, including:

- Rhythm: regional jazz styles often have a distinctive rhythmic feel that is influenced by the local musical traditions.

- Harmony: regional jazz styles may have different chord progressions and voicings that are influenced by local musical traditions.

- Musical Improvisation: regional jazz styles may have different approaches to improvisation, such as the use of different scales, modes, and phrasing.

- Musical Instrumentation: the choice of instruments used, the way they are played, and their tone can also contribute to a regional sound.

- Song selection: regional jazz styles may also feature different types of songs or composers that are unique to that region.

An expert knowledgeable about regional jazz sounds would be able to recognize these elements and identify the specific regional sound they belong to.

ChatGPT: (Response 7) Sure, specific elements of a distinctive regional sound in jazz include the use of certain instruments, rhythms, melodies, harmonies, and improvisational approaches that are unique to that region. For example, New Orleans jazz is often characterized by a strong use of brass instruments, collective improvisation, and a swing-based rhythm, while Chicago jazz often features a heavy emphasis on blues and swing. Similarly, bebop, which originated in New York City, is known for its complex chord progressions and intricate solos. Additionally, a region's cultural influences, such as its history and local musical traditions, can also shape its distinctive sound in jazz.

ChatGPT: (Response 8) Regional sounds in jazz can be influenced by various factors such as the local musical traditions, instruments available, the influence of popular music, the presence of certain musicians, and the overall cultural context. Some specific elements that could be used to identify a regional jazz sound include:

- Melodic phrasing: the way musicians play and articulate a melody.

- Rhythmic grooves: the specific patterns and styles used to create a beat.

- Use of harmony and chord progressions: the chords and chord sequences used in the music.

- Improvisation style: the way musicians improvise and add their own creative flourishes to the music.

- Instrumentation: the types of instruments used and the way they are played, including the use of regional instruments.

These elements, when taken together, can create a unique and recognizable sound for a particular region or city. However, it is worth noting that not all jazz from a particular region will sound the same and that jazz is a constantly evolving genre..

ChatGPT: (Response 9) There are various elements of jazz sound that can be associated with specific regions, such as:

- New Orleans: The use of early brass band instruments, collective improvisation, and a syncopated rhythm called "swing".

- Kansas City: A heavy use of blues and blues-based progressions, complex rhythms, and an emphasis on virtuosic soloing.

- Chicago: Use of big-band arrangements, a more structured approach to improvisation, and a focus on swinging rhythm.

- Los Angeles: The incorporation of Latin and bebop influences, an emphasis on melody and composition, and a lighter, smoother approach to swing.

These elements are not always exclusive to a particular region and can be found in different combinations and variations in different places, but they can serve as markers for listeners who are familiar with regional jazz sounds.

ChatGPT: (Response 10) Regional jazz sounds can be influenced by a variety of factors, including the musical traditions and influences of the area, the instrumentation and musical practices of local musicians, and the cultural and historical context of the region. Some possible elements that could be recognized by an expert include unique rhythmic patterns, specific instrumentation (such as the use of a certain type of percussion instrument), particular modes or scales, and specific harmonies or chord progressions. Additionally, certain styles of improvisation or specific approaches to phrasing and timing may be associated with a particular region's jazz sound.

ChatGPT: (Response 11) An expert knowledgeable about regional jazz sounds may recognize elements such as:

- Groove and rhythm: the feel and syncopation of the beat.

- Harmony and chord progression: the way chords are used and how they create progressions.

- Musical Instrumentation: the types of instruments used and how they are featured in the ensemble.

- Jazz Improvisation: the style, phrasing, and approach of soloists.

- Arrangement: the way the different elements of the ensemble are combined and layered to create the overall sound.

It's important to note that these elements can vary within regions and individual musicians, so a specific regional sound is often a generalization and not a rigid definition..

ChatGPT: (Response 12) There are several elements of a jazz performance that can give it a distinct regional sound. For example:

- Groove: Different regions may have their own swing or groove, the feel or rhythm of the music, that sets it apart from other regions.

- Harmony: Different regions may have different harmonic practices, such as the use of different chord progressions or the use of certain scales and modes.

- Improvisation: Different regions may have their own approaches to improvisation, such as the use of specific techniques, phrasing, or musical vocabulary.

- Musical Instrumentation: Different regions may have different instruments that are commonly used in jazz, such as horns, piano, guitar, or drums, and the use of those instruments can add to a region's distinctive sound.

- Cultural influences: The cultural influences of a region can also shape the sound of jazz in that area, such as the use of traditional music forms or musical styles from other cultures.

An expert knowledgeable about regional jazz sounds can recognize these elements and identify the region of origin of a jazz performance.

ChatGPT: (Response 13) Expert listeners may recognize specific elements of a regional sound in jazz such as:

- Rhythmic patterns and grooves.

- Harmonic choices and chord progressions.

- Improvisational styles and techniques.

- Use of blues and gospel influences.

- Instrumentation and orchestration.

- Influences from local musical traditions.

These elements can vary in different regions and contribute to the creation of distinctive regional jazz sounds.[15] (bold and hyperlinks not in original)

PoJ.fm chats with ChatGPT (January 30 2023 version) on the city of Los Angeles having a unique jazz sound[edit]

NOTE: All bold, hyperlinks, information inside of square brackets, and images added below by PoJ.fm and not by ChatGPT.

PoJ.fm: What was distinctive about jazz from the city of Los Angeles?