Sp19. Jazz and Race

Contents

- 1 Discussion

- 2 Introduction

- 3 Reasons why jazz remains a predominantly black musical phenomenon

- 4 Reasons why the Afro-American race gets credit for jazz

- 5 Black Superstars of jazz in mid-twentieth century

- 6 Reasons why jazz DOES NOT remain an exclusively black musical phenomenon

- 7 Jazz around the Globe by 1922

- 8 Jazz is not just American in its history

- 9 Jazz is not like classical music in performance

- 10 The professional baseball analogy argument

- 11 Jazz musicians from seventy countries

- 12 Post-structuralist Critiques and Their Implications

- 13 Internet resources on jazz and race

- 14 NOTES

Discussion

Introduction

Jazz and race is a complex topic area. There is no question that the earliest musicians who created jazz as a musical genre were generally of Afro-American origin, but not exclusively since musicians such as Jelly Roll Morton (1890–1941) and Sydney Bechet (1897–1959) were Creoles. Any history of jazz acknowledges that the vast majority of early jazz performers were non-white players. Still, there remains a problem because even in its earliest history non-black players were involved in jazz music production and in helping to make jazz a cultural phenomena.

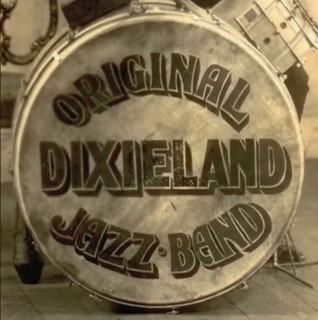

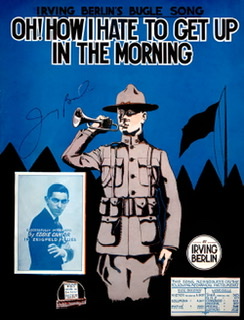

It is often claimed that the very first recorded jazz in 1917  was done by the all-white group The Original Dixieland Jazz Band

was done by the all-white group The Original Dixieland Jazz Band

, but see John Edward Hasse's Smithsonian article for possible black musician precursors.[1]

, but see John Edward Hasse's Smithsonian article for possible black musician precursors.[1]

The late Richard Havers (1951–2017), former editor-in-chief and cofounder of UDiscoverMusic.com, reports on candidates for the earliest jazz recordings by both white and black musicians.

“The truth is that a number of other artists could make that claim [of having recorded jazz first]. There was Arthur Collins and Byron G Harlan, who released “That Funny Jas Band From Dixieland” [(click on it to listen)] in April 1917; it’s just as jazzy as the ODJB. Borbee’s “Jass” Orchestra [(click to hear five of their songs)] recorded two songs nearly two weeks before the ODJB entered the studio, but they did not get released until July 1917. Like the ODJB, both these artists were white.”[2] (bold not in original)

White vocalists Arthur Collins (1864–1933) (sang baritone and known at the time as the King of the Ragtime Singers) with his singing partner tenor Byron G. Harlan (1861–1936) were primarily Ragtime singers who popularized so-called coon songs and the use of vocal caricatures of black people, Irishmen, and farmers. Even the claim that he and Harlan recorded the earliest record known to mention jazz, "That Funny Jas Band from Dixieland" (Victor 18235, recorded January 12, 1917) does not require that the song that got recorded really was jazz music. Wikipedia reports that Barry Kernfeld (b. 1950) qualifies in The Blackwell Guide to Recorded Jazz that “Originally simply called "jazz," the music of early jazz bands is today often referred to as "Dixieland" or "New Orleans jazz," to distinguish it from more recent subgenres.”[3] You can listen to the very talky song "That Funny Jas Band from Dixieland" here.

The first Black musicians to make a jazz record.

Among the contenders for the first Black musicians to make a jazz record are pianist Charles A. Prince’s (1869–1937) Band, who recorded “Memphis Blues” in 1914, and then in 1915 he became the first to record a version of W. C. Handy’s (1873–1958) “St Louis Blues.” In April 1917, Charles A. Prince’s Band recorded “Hong Kong,” a “Jazz One-Step.” Not to be outdone, W. C. Handy’s band were making recordings in September 1917. There was also Wilbur Sweatman’s (1882–1961) Original Jass Band, and the Six Brown Brothers in the summer of 1917, though there is a debate as to whether some of these records are jazz or its close cousin, Ragtime.[4] (bold not in original)

Jazz has been in Europe since at least World War 1 (1914–1918), when James Reese Europe's (1891–1919) 369th Infantry Regimental military band played throughout the European continent.

“During World War I, [James Reese] Europe obtained a commission in the New York Army National Guard, where he fought as a lieutenant with the 369th Infantry Regiment (the "Harlem Hellfighters") when it was assigned to the French Army. He went on to direct the regimental band to great acclaim. In February and March 1918, Europe and his military band travelled over 2,000 miles in France, performing for British, French and American military audiences, as well as French civilians. Europe's "Hellfighters" also made their first recordings in France for the Pathé brothers. The first concert included a French march, and the "Stars and Stripes Forever" as well as syncopated numbers such as "The Memphis Blues," which, according to a later description of the concert by band member Noble Sissle " . . . started ragtimitis in France."”[5] (bold not in original)

After originating in America, jazz disseminated around the Earth, predominantly first in Europe and then everywhere else. Jazz is now played on every continent and country by that country's inhabitants. Is it reasonable to think that at the current time in the 21st century jazz remains only a black music phenomena? Granted that jazz began as a predominantly culturally black music, should one continue to believe that it remains an exclusively black music genre?

Reasons why jazz remains a predominantly black musical phenomenon

In his Music: A Subversive History, American jazz critic and music historian, Ted Gioia (b. 1957) attests to and argues for the general claim that musical innovations typically derive from the underclasses of societies.

Music critic Robert Christgau (b. 1942) in his Los Angeles Times review reports that Gioia's music history book was “dauntingly ambitious, obsessively researched labor of cultural provocation” regarding the global history of music that reveals how songs have shifted societies and sparked revolutions.[6]

The blurb for Gioia's book reports that he argues for the claim that musical innovations, such as new music genres, almost always start by musicians at the margins of any society.

“Histories of music overwhelmingly suppress stories of the outsiders and rebels who created musical revolutions and instead celebrate the mainstream assimilators who borrowed innovations, diluted their impact, and disguised their sources. In Music: A Subversive History, Ted Gioia reclaims the story of music for the riffraff, insurgents, and provocateurs. Gioia tells a four-thousand-year history of music as a global source of power, change, and upheaval. He shows how outcasts, immigrants, slaves, and others at the margins of society have repeatedly served as trailblazers of musical expression, reinventing our most cherished songs from ancient times all the way to the jazz, reggae, and hip-hop sounds of the current day.[7] (bold and bold italic not in original)

Did what Gioia report happen to jazz? Yes, it did.

“The whole story is very similar to the rise of black music in the United States, where the elites recognized at a very early stage the expressive power of the songs of the African-American populace, and were torn between their desire to repress it and their even deeper desire to listen to it. In fact, this same phenomenon occurs at almost every crucial moment of innovation in the history of music—you can find in ancient Rome, China, the Islamic world, and in many other settings.”[8] (bold not in original)

Music journalist, book reviewer, essayist, and critic Robert Christgau (b. 1942) was not as impressed as Gioia about musical innovations coming from repressed people in his review "The history of music—all of it—in 400-plus pages."

“He’s [Gioia] also rather too impressed at how the history of music is dominated by innovators who are first shunned by establishment tastemakers and then absorbed by them. That’s how human progress works, especially in the arts.[9] (bold not in original)

We will get to more on this in a moment. But first it would seem that Ragtime may have been somewhat the exception. Ragtime composers were perhaps an exception to their music getting watered down for a mainstream audience since the composed Ragtime music had been written down on score sheets and often the music was played through a player piano. A player piano is a mechanical device that uses punched paper rolls to program the piano as to how to power the keyboard hitting the wire strings inside of the piano. This produces an unvarying reproduction of the composer's, or the recorded performer's, main intentions for how to play that particular piece of music.

Reasons why the Afro-American race gets credit for jazz

The genesis of jazz can be credited to Afro-Americans for multiple reasons.

(1) The blues was an Afro-American creation consistent with African American culture.

(2) Ragtime was not an exclusively Afro-American creation, but two of its three biggest stars were so, namely, Scott Joplin (1868–1917) and James Scott (1885–1938). The third prominent composer of classic ragtime was the Irish American Joseph Lamb (1887–1960). Also, there were many other white ragtime composers. Still, since Ragtime preceded jazz and incorporated syncopation it is natural to claim Ragtime as an influence on early jazz and because two of its biggest three Ragtime composers were Afro-Americans, this supports the cultural heritage claims regarding jazz.

(2.5) Jazz incorporated both blues and Ragtime so this makes jazz incorporating Afro-American music. Gunther Schuller in his first volume on the earliest jazz history recounts the African elements found in the blues and how it was incorporated into jazz as explained at Wikipedia, for Gunther Schuller's Early Jazz: Its Roots and Musical Development (New York: Oxford University Press, 1968), Ch. 1 "The Origins."

“The section on form covers African elements, European influences, and forms developed by African-Americans in the South. Schuller concludes that the blues "left enough room to preserve a number of African rhythmic-melodic characteristics." In a brief discussion of the role of harmony in the origins of jazz, the book notes that African and European systems of harmony overlapped sufficiently to allow their synthesis without "profound problems." The section on melodyagain finds African characteristics in a fundamental characteristic of jazz melody: the use of blue notes. An additional African influence is the way that melody in predecessors of jazz followed speech characteristics.

A brief section on timbre again emphasizes the African roots of an emphasis on the individuality of a performer's tone color. Schuller notes that "African instrumentation reflects the vocal quality of African speech." He cites various jazz performers for the natural quality of their sound production, sound that makes each performer readily identifiable. A final brief section in this chapter, on improvisation, states that group improvisation, a hallmark of early jazz, is a distinctively African practice. Schuller counters a variety of other theories of the historical basis of jazz improvisation. He summarizes the "Origins" chapter by observing, "Many more aspects of jazz derive directly from African musical-social traditions than has been assumed."”[10] (bold not in original)

(3) Many of the major contributors to jazz innovations have been African-American, or Creole, and Creoles were considered to be non-white.

(A) = Afro-American/Black

(C) = Louisiana Creole/Creoles of Color

(W) = White/Caucasian

Earliest jazz was from Buddy Bolden (A) and his Afro-American band members. The leading jazz bands of the day were mostly all Afro-American, including King Oliver's (A) with trumpet innovator, Louis Armstrong (A). The early jazz recordings were mostly by Afro-Americans or Creoles in 1923, including King Oliver (A), Freddie Keppard (C), Louis Armstrong (A), Bennie Moten (A), Johnny Dodds (A), Jimmy Noone (A), trombonist Jimmy Harrison (A), the trumpeters Johnny Dunn (A) and Jabbo Smith (A) and pianist Earl Hines (A), and the two Creoles Jelly Roll Morton (C), and Sidney Bechet (C). Afro-Americans such as King Oliver brought jazz to Chicago. Jazz musicians coming out of Harlem, a well known Afro-American region of New York City included Harlem stride pianists such as James P. Johnson (A) and Johnson's disciple Fats Waller (A).

1. Scott Joplin (ca. 1867 – April 1, 1917) — Afro-American/Black

2. Jelly Roll Morton (October 20, 1885 – July 10, 1941) — Louisiana Creole/Creoles of Color

3. James Reese Europe (22 February 1881 – 9 May 1919) — Afro-American/Black

4. King Oliver (May 11, 1885 – April 10, 1938) — Afro-American/Black

5. Freddie Keppard (February 27, 1890 – July 15, 1933) — Louisiana Creole/Creoles of Color

6. Louis Armstrong (August 4, 1901 – July 6, 1971) — Afro-American/Black

7. Fletcher Henderson (December 18, 1897 – December 29, 1952) — Afro-American/Black

8. Sidney Bechet (May 14, 1897 – May 14, 1959) — Louisiana Creole/Creoles of Color

9. ODJB (Original Dixieland JassBand) (1917) — White/Caucasian

10. Bix Biederbecke (March 10, 1903 – August 6, 1931) — White/Caucasian

According to Ted Gioia (b. 1957) in his 1997 History of Jazz (now in its third edition as of March 1, 2021), orchestral jazz developed from early New Orleans jazz. The African-American musicians pioneering the genre prior to 1920 migrating from New Orleans to Chicago and New York in the early 1920s, bringing more jazz north and east. Over time, Harlem in New York—an established Afro-American community—became the genre's cultural center.

Jazz advanced as arrangements advanced requiring innovative arrangers and bandleaders. Leading the charge here were Afro-Americans Fletcher Henderson and his arranger Don Redman (a prime mover in this band), McKinney's Cotton Pickers, Charlie Johnson's Paradise Ten, and the Missourians, Bennie Moten's orchestra, Jesse Stone's Blues Serenaders, Troy Floyd's orchestra, Walter Page's Blue Devils, and Alphonso Trent's orchestra, and in Denver Andy Kirk and Jimmie Lunceford.

In the discussion of Kansas City jazz in the 1920s, Schuller observes that the region was the birthplace of Ragtime, an important popular music in the area.

Afro-American James Reese Europe was the best known earliest jazz band leader from 1910 to his death in 1919. Wikipedia: James Reece Europe reports that Europe was an “American ragtime and early jazz bandleader, arranger, and composer and the leading figure on the African Americans music scene of New York City in the 1910s.” and it was James Reece Europe who brought Ragtime and proto-jazz to France in 1917–18.

In the 1930s, jazz focused on big bands, such as those by Afro-Americans Duke Ellington, Jimmie Lunceford, Bennie Moten, Cab Calloway, Earl Hines, and Fletcher Henderson, and white bands from the 1920s led by the likes of Jean Goldkette, Russ Morgan and Isham Jones. An early milestone in the era was from "the King of Swing" Benny Goodman's performance at the Palomar Ballroom in Los Angeles on August 21, 1935, bringing the music to the rest of the country. The 1930s also became the era of other great Afro-American soloists: the tenor saxophonists Coleman Hawkins, Ben Webster and Lester Young; the alto saxophonists Benny Carter and Johnny Hodges; the drummers Chick Webb, Gene Krupa, Jo Jones and Sid Catlett; the pianists Fats Waller and Teddy Wilson; the trumpeters Louis Armstrong, Roy Eldridge, Bunny Berigan, and Rex Stewart.

There were still significant non-Afro-American big swing bands in the 1930s lead by Jimmy Dorsey, his brother Tommy Dorsey, Glenn Miller, Benny Goodman, his future rival Artie Shaw, Woody Herman, who departed the Isham Jones band in 1936 to start his own band, Stan Kenton, and Boyd Raeburn.

(4) Jazz as a music has musical aspects found in and influenced by African music, including use of a pentatonic scale and having a particular promotion of the use of rhythm, involving syncopation.

(5) If there had been no slaves brought from Africa jazz would not have developed in the United States. Therefore a primary cause and responsible for the creation of jazz were Afro-Americans.

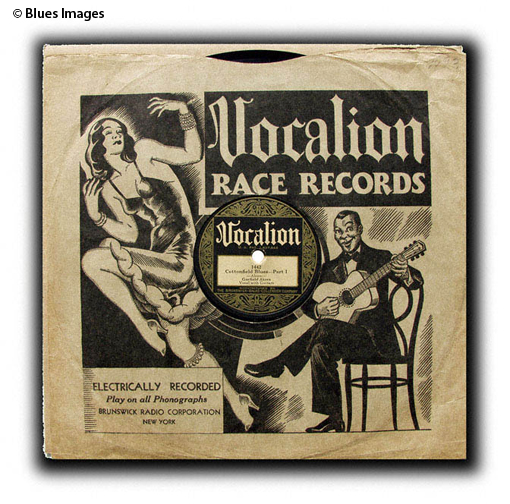

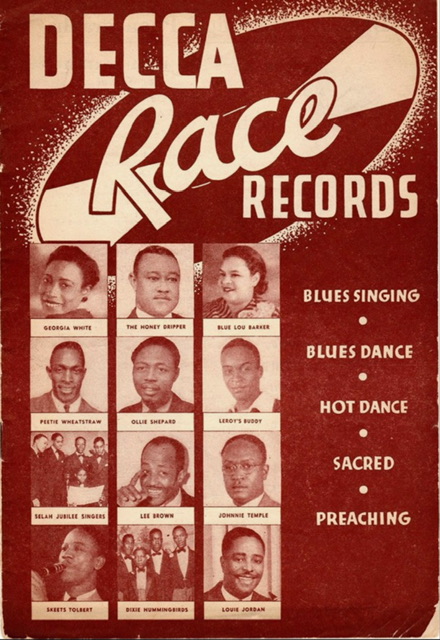

(6) Jazz was perceived at the time as being a form of music produced by Afro-Americans. A major category for labeling music made by Afro-Americans was race records made to be played on a phonograph. Race records were marketed to non-white people and included jazz recordings in addition to those records of blues vocalists or rhythm and blues musicians.

“Race records were 78-rpm phonograph records marketed to African Americans between the 1920s and 1940s. They primarily contained race music, comprising various African-American musical genres, including blues, jazz, and gospel music, and also comedy. These records were, at the time, the majority of commercial recordings of African American artists in the U.S., and few African American artists were marketed to white audiences. Race records were marketed by Okeh Records, Emerson Records, Vocalion Records, Victor Talking Machine Company, Paramount Records, and several other companies.”[11] (bold not in original)

NOTE: Click on image for source.

“Prior to the emergence of rhythm & blues as a musical genre in the 1940s, "race music" and "race records" were terms used to categorize practically all types of African-American music. Race records were the first examples of popular music recorded by and marketed to black Americans. Reflecting the segregated status of American society and culture, race records were separate catalogs of African-American music. Prior to the 1940s, African Americans were scarcely represented on radio, and live performances were largely limited to segregated venues. Race music and records, therefore, were also the primary medium for African-American musical expression during the 1920s and 1930s; an estimated 15,000 titles were released on race records—approximately 10,000 blues, 3,250 jazz, and 1,750 gospel songs were produced during those years.The terms "race music" and "race records" had conflicting meanings. In one respect, they were indicative of segregation in the 1920s. Race records were separated from the recordings of white musicians, records solely because of the race of the artists. On the other hand, the terms represented an emerging awareness by the recording industry of African-American audiences. The term "race" was not pejorative; in fact "race was symbolic of black pride, militancy, and solidarity in the 1920s, and it was generally favored over colored or Negro by African-American city dwellers," noted scholar William Barlow in "Cashing In: 1900-1939." The term "race records" first appeared in the Chicago Defender, an African-American newspaper, within an OKeh advertisement in 1922.

Race music and records in the 1920s were characterized by the popularity of two significant genres of music and the dominance of three race record labels. In particular, jazz and blues became part of the American musical idiom in the 1920s, popularized in large part through recordings released on Columbia, Paramount, and OKeh. Jazz, the dominant American indigenous popular music, emerged from the New Orleans area to become national, and eventually international, in popularity and practice. For example, Joe "King" Oliver was a seminal figure in jazz, and his band featured Louis Armstrong. Oliver's Creole Jazz Band came out of New Orleans and was a mainstay in several Chicago clubs; the group recorded some of the earliest and most influential jazz records for the Gennett label. Likewise, Jelly Roll Morton, an influential pianist from New Orleans, recorded groundbreaking songs for the Gennett label.

In the 1930s race music was expanded by the popularity of swing. Swing grew out of big band jazz ensembles in the 1920s. Unlike the jazz bands of the 1920s, however, swing was more often arranged and scored, instead of improvised, and used reed instruments as well as the brass instruments that dominated earlier jazz. Swing in the 1930s was epitomized by the Fletcher Henderson Band which featured Louis Armstrong on trumpet, Coleman Hawkins on tenor saxophone, and arranger Don Redman. Other notable swing bands during this period included Chick Webb's band, which had vocalist Ella Fitzgerald, Jimmy Lunceford's Band, Duke Ellington's Orchestra, Count Basie's Orchestra, and Cab Calloway's Orchestra.”[12] (bold not in original)

All of these musicians were Afro-American: Fletcher Henderson, Louis Armstrong, Coleman Hawkins, Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Cab Calloway. These were the leaders in jazz and the black musical community from the 1930s to 1940 and beyond.

“By the mid-1920s, established major labels like Victor and Columbia found themselves outpaced by smaller companies like Gennett, Okeh, and Paramount, who recorded the new genres of the age—“race” (blues and related genres); “hillbilly” (country and related genres) and “jazz” (the popular music of the era, and antecedent to various jazz sub-genres to come)—in their ability to delineate new talent and define new taste cultures. These genre categories functioned as a means for the industry to structure these “new” types of music for specific audiences through linking specific aesthetic styles with social attitudes and beliefs connected to the music.”[13]

Kyle Stewart Barnett wrote in his dissertation about how smaller record labels, such as Gennett, helped promote jazz and black music.

“One of this dissertation’s central hypotheses is that specific cultures at recording companies affected the selection, promotion and sale of its musical output, and thus small label interest in jazz during the 1920s represents a promising case study. And if jazz as a genre embodied a given set of social, cultural and aesthetic designations that resonated with consumers, those designations are generally (if not specifically) traceable through what little record company history remains. Gennett Records, of Richmond, Indiana, was the first of the upstart labels of the 1910s to challenge the dominance of the Big Three (Victor, Columbia, and Edison). Gennett was an important participant in the popularization of jazz, which along with the race and hillbilly genres that followed would reshape the trajectory of U.S. popular music. The emergence of jazz as a genre can be better understood by tracing how (and where) everyday business practices met socio-cultural attitudes in Gennett’s mode of production: its institutional culture, its scouting and recording practices, its means of selection for releases, and its advertising strategies.”“Columbia Records recorded jazz as early as 1917 (“Darktown Strutter’s Ball” and “Indiana” by the Original Dixieland Jass, and later Jazz, Band), . . . Gennett’s lasting reputation is often associated with jazz, primarily due to the company’s recording some of jazz’s foundational moments, despite the fact that few of these now-treasured recordings likely sold much upon first release.”[14] (bold not in original)

“Despite such experiments, Gennett usually returned to those records that sold most reliably. Judging on the number of releases that would have been loosely construed as jazz at the time, Gennett must have had some economic success with the trend. The releases tended to be based on the style and popularity of the all-white Original Dixieland Jazz Band, whose Victor releases first gained popularity in 1917—starting a jazz craze that led to the recording of both black and white jazz groups. Defining releases from Gennett (despite poor sales upon initial release) include Joe “King” Oliver’s “Dippermouth Blues,” recorded on June 23, 1923 with a young Louis Armstrong in his band, and Bix Beiderbecke and his Rhythm Jugglers first recorded “Davenport Blues” for Gennett on January 26, 1925. Hoagy Carmichael first recorded “Star Dust” for Gennett on October 31, 1927, backed by Emil Seidel and his Orchestra with the Dorsey Brothers sitting in. The song only became a hit after the company took another chance on a song that initially had performed poorly by re-recording it later. Jelly Roll Morton and the New Orleans Rhythm Kings recorded “Mr. Jelly Lord” for Gennett, in what has been purported to be the first interracial recording session in the U.S. on February 24, 1926.During this period, “jazz” functioned as a defining term for a given song style—or perhaps even more importantly, a kind of dance. Jazz in its early period was known as a sub-section of dance music, but through the decade would increasingly become a term for the new dance music in general. Paradoxically, the popularization of the term “jazz” was linked with the controversy surrounding the new music’s improvisational style, rhythmic syncopation, and connection with African-Americans.”[15] (bold and bold italic not in original)

Relevance of the etymology of the word "jazz"

Alan P. Merriam and Fradley H. Garner, "Jazz—the Word," Ethnomusicology XII.3 (1968): 389, 93.

“We have come to a point in the study of the word where it seems wise to review the past theories although even now it is probably impossible to decide surely which will ultimately prove to be correct.” Alan P. Merriam and Fradley H. Garner, "Jazz—the Word," Ethnomusicology XII.3 (1968): 373.

Ch. 2, Footnote 31. See Ted Gioia, The History of Jazz (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997) 36. Gioia notes that those musicians who were active were black (Buddy Bolden, Bunk Johnson, Joe “King” Oliver, Mutt Carey), Creole (Jelly Roll Morton, Sidney Bechet, Kid Ory, Freddie Keppard) and white (Nick LaRocca, Sharkey Bonano, and Papa Jack Laine), as the music transcended those racially segregated groups in such close proximity.

“The question as to where, how, and when the word "jazz" was first used as applied to music is as much of a puzzle as its ultimate origin, with various writers holding widely different points of view.” Alan P. Merriam and Fradley H. Garner, "Jazz—the Word," Ethnomusicology XII.3 (1968): 386.

Table of male Afro-American jazz musicians in early jazz

| Table of Male Afro-American Jazz Musicians | ||

|---|---|---|

| Musician | Birth–Death dates | Country — Musical Instrument(s) & Roles |

| Chris Kelly | (1890–1929) | American (New Orleans) trumpeter 🎺 , best known for his early contributions on the New Orleans jazz scene. Throughout the 1920s, he was a regular collaborator with clarinetist George Lewis. No photographs or recordings have survived of Kelly. |

| Buddie Petit | (1897–1931) | American early jazz cornetist.  (Animated Buddy Petit face by PoJ.fm) Born in Louisiana, he replaced Freddie Keppard in the Eagle Band (earlier held by Buddy Bolden) when Keppard departed. He played in Los Angeles with Jelly Roll Morton and Bill Johnson in 1917. Returning to New Orleans, Petit spent the rest of his career in the area around greater New Orleans. Holding out for more money from Okeh Records, he was never recorded.  (Photograph was colorized and enhanced by PoJ.fm) |

| George Lewis | (1900–1968) | American clarinetist. During the 1920s, he founded the New Orleans Stompers and over this decade he worked with Chris Kelly, Buddy Petit, Kid Rena, and was a member of the Eureka Brass Band and the Olympia Orchestra. In the 1930s, he played with Bunk Johnson, De De Pierce, and Billie Pierce. He recorded with Johnson in the early 1940s and with Kid Shots Madison. Alan Lomax brought Lewis on a Rudi Blesh radio show in 1942 in which Lewis played "Woodchopper's Ball" by Woody Herman. His friends, banjoist Lawrence Marrero and double bassist Alcide Pavageau. Lewis continued to perform with Bunk Johnson's band through 1946 including a trip to New York City. Band members included Johnson, Marrero, Pavageau, trombonist Jim Robinson, pianist Alton Purnell, and drummer Baby Dodds. After Bunk Johnson retired, Lewis took over leadership of the band, which included Robinson, Pavageau, Marrero, Purnell, Joe Watkins, and a succession of New Orleans trumpeters: Elmer Talbert, Kid Howard, and Percy Humphrey. Starting in 1949, Lewis was a regular on Bourbon Street clubs and radio station WDSU. He became a leader of the New Orleans revival. In the late 1940s and early1950s, his recordings reached the UK and influenced clarinetists Monty Sunshine and Acker Bilk. They became important contributors to the traditional jazz scene in the UK and accompanied Lewis when he toured the country. Lewis visited England in 1957 and again in 1959. In 1959, he visited Denmark and played at Jazzhus Montmartre in Copenhagen. Beginning in the 1960s, he played regularly at Preservation Hall in New Orleans as leader of the Preservation Hall Jazz Band until shortly before his death. |

| Kid Rena pronounced "ruh-nay" |

(1898–1949) | American (New Orleans) jazz trumpeter 🎺.  Louis Armstrong and Kid Rena played in the same waif's home band. When Armstrong joined the band on the S.S. Capitol, Rena was named his replacement in Kid Ory's band in 1919 who he continued to perform with until 1922, when Ory moved to Los Angeles, so that year Rena formed his own band. Rena played all the New Orleans jazz houses as well as in Chicago in 1923–24. He led the Eureka Brass Band in the late 1920s, remaining with them until 1932, when he formed his own brass band. In 1940, Heywood Hale Broun asked Kid Rena to make eight recordings at the Hotel Roosevelt by local radio station WWL on August 21, 1940. These recordings are widely regarded as the first recordings of the revival of the New Orleans style in the 1940s. |

| Pops Foster | (1892–1969) | American slap bassist, trumpet, and tuba player. Stuff |

| [1] | (1890–1963) | American clarinetist.

|

| [2] | (1890–1963) | American clarinetist.

|

| [3] | (1890–1963) | American clarinetist.

|

| [4] | (1890–1963) | American clarinetist.

|

| [5] | (1890–1963) | American clarinetist.

|

| [6] | (1890–1963) | American clarinetist.

|

Was jazz a music promoted by an underclass of musicians in America 🇺🇸? Undoubtedly. There are several reason supporting such a conclusion. First, professional musicians are in the entertainment business. The entertainment business in America from 1890 until 1920 was considered a less than noble profession. Entertainers are associated with a more sleazy side of society—sex, booze, drugs, and music. Second, slavery ended in America in 1865. People of color were suppressed by the prejudiced elite white society power-holders and government officials. Jazz began by 1895 with Buddy Bolden mixing multiple genres of music with syncopation, improvisation, and technical brilliance. In Bolden's case, one of his areas of technical brilliance was his capacity for playing extremely loudly. Improvisation is a freedom to create and express oneself musically.

“Yet the decisive creative currents in this society came from the African American underclass. Should this surprise us? The reputation of musicians, and other performing artists, as outsiders or pariahs, as practitioners who exist at the limits of the socially acceptable, has a long tradition dating back to ancient times.”[16] (bold not in original)

Black Superstars of jazz in mid-twentieth century

Exclusively? Hardly anything is exclusive. But the preponderance of players, and most importantly, innovators in early (1895–1920) and middle jazz (1930–1950) were Afro-Americans, and credit should be given to the culture responsible for generating the bulk of the music and its features.

Saxophonists

Afro-American Saxophonists

The following saxophonist rankings and their descriptions by Charles Waring are from UDiscoverMusic.com's "The 50 Best Jazz Saxophonists Of All Time" published on September 13, 2021. Numbers 4 (Stan Getz), 8 (Art Pepper), 22 (Zoot Sims), 27, 32, 37, 40, 43–46, 49 and 50 were the only non-Afro-Americans; 13 out of 50 = 26%.

- 50: Gato Barbieri (1932–2016)

With his raw, wailing tenor sax sound, Argentina-born Leandro “Gato” Barbieri plowed a Coltrane-esque avant-garde furrow in the late 60s before making a more accessible form of music that embraced his Latin American roots. From the 70s onwards, Barbieri leaned towards smooth jazz settings for his music, though his brooding tenor saxophone never lost its visceral intensity.

- 49: Pepper Adams (1930–1986)

Baritone specialist Park “Pepper” Adams came from Michigan and was a stalwart of the Detroit scene, where he played with Donald Byrd in the late 50s and early 60s. An in-demand sideman due to the deep sonorities and dark textures he created on his baritone sax, Adams was an integral member of the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra between 1966 and 1977.

- 48: Rahsaan Roland Kirk (1935–1977)

Regarded as an eccentric blind maverick by some for functioning as a one-man band on stage (he could play three horns at once and had a variety of exotic instruments dangling from his neck and shoulders), Kirk’s multi-tasking skills meant that his prowess on the saxophone has been overlooked. He was, though, a superb tenor saxophonist who was at home with both hard bop, modal jazz, and R&B, and easily earns his place among the world’s best jazz saxophonists. Rahsaan Roland Kirk - "Volunteered Slavery" (Montreux 1972)

- 47: Pharoah Sanders (1940–September 24, 2022)

An acolyte of John Coltrane (with whom he played between 1965 and ’67), tenor/soprano saxophonist and flutist Sanders helped to bring both a cosmic and deep spiritual vibe to jazz in the late 60s and early 70s. A prolific purple patch at the Impulse! label between 1969 and 1974 (which yielded ten LPs) cemented his place in the pantheon of best jazz saxophonists. Sanders’ music also tapped into the music of other cultures.

- 42: Arthur Blythe (1940–2017)

Brought up on a strict diet of rhythm’n’blues, this Los Angeles altoist played in the bands of Gil Evans and Chico Hamilton before making his mark as a proponent of avant-garde jazz in the late 70s. Even so, while his music always looked forward, Blythe never lost sight of the traditions of the best jazz saxophonists before him. As well as having a distinctive and emotionally intense reed sound, Blythe was also a fine composer. Arthur Blythe Trio - "Chivas Jazz Festival 2003 #7"

- 41: Jimmy Heath (1926–2020)

One of three noted jazz musician siblings (his brothers are drummer Percy and bassist Albert Heath), this Philly saxophonist started his career in the 40s and switched from alto to tenor sax to try and avoid comparisons with fellow bebopper Charlie Parker (Heath was dubbed Little Bird for a time). Heath has played with all the jazz greats (from Miles Davis and Milt Jackson to Freddie Hubbard). Jimmy Heath & WDR BIG BAND - "Bruh Slim"

- 39: Yusef Lateef (1920–2013)

Arriving in the world as William Huddleston, Lateef pioneered the incorporation of musical elements from other cultures into his music. He was particularly fond of Eastern music and, as well as playing tenor saxophone, which he played in a hard bop style, he was a fluent flautist and oboist.

- 38: Harold Land (1928–2001)

A member of the trailblazing Clifford Brown/Max Roach Quintet, this Texas tenor titan was at the birth of hard bop in the early 50s and later based himself in Los Angeles, where he offered a more vigorous alternative to the West Coast’s omnipresent cool sound. He later teamed up with vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson for an acclaimed series of collaborations. Like many of the best jazz saxophonists, Land’s brooding tenor sound, with its intense level of expression, was indebted to Coltrane.

- 36: Illinois Jacquet (1919–2004)

Famed for his staccato honking sound and catchy riffs, Jean-Baptiste “Illinois” Jacquet was an alto player from Louisiana who was raised in Texas and then moved to LA. It was there, in 1939, where he was recruited by bandleader Lionel Hampton (who persuaded Jacquet to swap his alto for a tenor sax). Jacquet’s rambunctious wild solo on Hampton’s “Flying Home” is widely perceived as representing the first manifestation on record of what would develop into rhythm’n’blues.

- 35: Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis (1922–1986)

From Culver City, California, Davis—given the name Lockjaw because his saxophone seemed almost glued to his mouth during his ultra-long solos—could play in a range of styles, though his calling card was a driving, blues-drenched hard bop. In the early 60s, he made a slew of combative but affable duet albums with his musical sparring partner, Johnny Griffin.

- 34: Al Cohn (1925–1988)

Alvin Cohn enjoyed a long and fruitful collaboration with fellow tenor Zoot Sims – and, together, the pair were considered by Jack Kerouac to be among the best jazz saxophonists of the 50s, and were asked to play on his 1959 poetry album Blues And Haikus. Cohn gained notoriety playing alongside Sims and Stan Getz in Woody Herman’s Second Herd during the late 40s, and, despite being born and raised in Brooklyn, he came to be associated with the West Coast cool sound. Cohn’s signature was a bright but full-bodied saxophone tone out of which he poured rivulets of mellifluous melody.

- 33: Benny Carter (1907–2003)

Harlem-born Carter’s main instrument was the alto sax, but he was also adept on the trumpet and clarinet. He made his recording debut in 1928 as a sideman, but, by the 30s, was leading his own swing band for which he was writing sophisticated charts that resulted in him doing arranging for the likes of Duke Ellington and Count Basie. A master of the swinging saxophone.

- 31: Sam Rivers (1923–2011)

Unique among the world’s best jazz saxophonists, Rivers was a multi-talented instrumentalist who played bass clarinet, flute, and piano besides excelling on tenor and soprano saxophones. He appeared on many jazz fans’ radar when he played with Miles Davis in 1964. After that he recorded for Blue Note, moving from an advanced hard-bop style that later edged towards the avant-garde.

- 30: Ike Quebec (1918–1963)

With his breathy, intimate tone, New Jersey native Quebec is mainly remembered as a seductive ballad player whose career started in the 40s. He spent a long time playing with Cab Calloway and also cut sides with Ella Fitzgerald and Coleman Hawkins before joining Blue Note in 1959, where he recorded some fine albums before his premature death from lung cancer, aged 44.

- 29: Lou Donaldson (born 1926)

This North Carolinian, Charlie Parker-influenced tenorist started to make his mark in the 50s, where his bluesy, soulful, and increasingly funkified hard bop style resulted in a slew of notable LPs for the Blue Note label. Donaldson also sat in as a sideman on notable sessions by Thelonious Monk, Clifford Brown, Art Blakey, and Jimmy Smith. Representative of his music is Donaldson's album "Blues Walk."

- 28: Stanley Turrentine (1934–2000)

Though he was dubbed The Sugar Man, there was nothing sickly sweet about this Pittsburgh-born tenor man’s robust and earthy style, whose DNA revealed blues cries, gospel cadences, and the influence of R&B saxophonist Illinois Jacquet. Turrentine played a mixture of hard bop and soul-jazz in the 60s at Blue Note; later, in the 70s, at CTI Records, he fused bop with Latin and pop music. Even among the best jazz saxophonists, few could play as soulfully as Stanley Turrentine.

- 26: Earl Bostic (1913–1965)

From Tulsa, Oklahoma, alto saxophonist Eugene Earl Bostic got his big break in vibraphonist Lionel Hampton’s band just before World War II. His fat, earthy tone and fluid, blues-infused style had a huge impact on a young John Coltrane, who cut his teeth in Bostic’s band in the early 50s. Bostic was extremely popular in the field of post-war R&B, racking up several US hits.

Born in New Orleans, the birthplace of jazz, Bechet started out on the clarinet and impressed at an early age before switching to the then-unfashionable and rarely heard soprano saxophone after discovering one on tour in a London junk shop in 1920. Soon after, he made his first recordings and caught the ear with his reedy soprano blowing, which had a tremulous vibrato and emotional intensity. The only entry in this list of the best jazz saxophonists to have been born in the 1800s, Bechet has the distinction of being the first significant saxophonist in jazz.

- 24: Eric Dolphy (1928–1964)

Though Dolphy died at a relatively young age (he was 36 when he tragically succumbed to a fatal diabetic coma), the reverberations from his pathfinding music can still be felt today. He was a virtuoso of the flute and bass clarinet but was also a fabulous alto sax player with a unique approach, and first came to the attention of the wider public when he began playing with Coltrane in the early 60s. Dolphy’s Blue Note LP, Out To Lunch, remains a touchstone of avant-garde jazz and his influence has extended beyond the genre. "Out To Lunch" (Remastered 1998/Rudy Van Gelder Edition)

- 23: Albert Ayler (1936–1970)

This Ohio free jazz and avant-garde saxophonist (who played the tenor, alto, and soprano varieties) didn’t live to see his 35th birthday, but today, almost 50 years after his death, his music and influence still casts a huge shadow in jazz. Drawing on gospel, blues cries, and marching-band music, Ayler patented a singular saxophone style that was raw, raucous, eerie, and driven by a primal energy. "Ghosts": Ghosts: Variation 1

- 22: Zoot Sims (1925–1985)

Californian tenor maestro John “Zoot” Sims took Lester Young’s sleek and mellow approach to jazz improv and fused it with the language of hard bop while filtering it through a cool West Coast sensibility. He played in many big bands (including those of Artie Shaw, Stan Kenton, and Buddy Rich) and was always conducive to working on collaborative projects with other saxophonists.

- 21: Gene Ammons (1925–1974)

Dubbed The Boss, Windy City native Gene “Jug” Ammons might have been the scion of boogie-woogie piano meister Albert Ammons, but he was drawn to the tenor saxophone and began his career in the 40s. An adherent of hard bop but with a style packed with blues feeling, Ammons was a prolific recording artist who embraced funkified soul-jazz in the 70s.

- 20: Benny Golson (born 1929)

The Philly-born tenorist made his mark with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers in the late 50s, and, as well as being noted for his sublime, hard bop-inflected playing, he was a fine composer, responsible for the classic tunes “I Remember Clifford,” “Killer Joe” and “Along Came Betty.”

- 19: Cannonball Adderley (1928–1975)

Florida-born altoist Adderley caused a sensation when he visited New York in 1955, and was soon snapped up to record the first of many albums during the next two decades. Like a number of the best jazz saxophonists of his era, he was a disciple of Charlie Parker, but nevertheless forged his own style, a soulful amalgam of bop, gospel and blues influences. He played on Miles Davis’ iconic modal jazz manifesto Kind Of Blue in 1959, but thereafter became a purveyor of soul jazz. In the late 60s and early 70s, Adderley’s music became more exploratory.

- 18: Hank Crawford (1934–2009)

A Memphis-born musician, Benny “Hank” Crawford, was one of the premier soul-jazz alto saxophonists of the 60s and 70s. His big break came when he joined Ray Charles’ band in 1958 (where he originally played baritone sax), which helped to launch his solo career at Atlantic Records. Crawford’s expressive, blues-inflected sound exerted a profound influence on a contemporary alto great, David Sanborn.

- 17: Sonny Stitt (1924–1982)

Dubbed the Lone Wolf, Boston-born Stitt started out as an alto saxophonist and began his recording career at the dawn of bebop during the close of the 40s. His florid, mellifluous style has often been compared with Charlie Parker’s (many accused Stitt of copying Parker), but he began to develop his own voice after switching to the tenor sax. A fearless improviser.

- 16: Ben Webster (1909–1973)

Though he was affectionately called The Brute, Ben Webster’s forceful style of playing was tempered with a high degree of tenderness, especially on ballads. With its breathy timbre, virile tone, and broad vibrato, Webster’s bluesy tenor saxophone sound is one of the most readily identifiable in jazz. He spent several years as a featured soloist in Duke Ellington’s Orchestra, an important group that also nurtured great saxophonists like Kenny Garrett.

- 15: Wayne Shorter (born 1933)

This Newark, New Jersey, composer and saxophonist (who alternates between soprano and tenor) enjoyed mainstream fame as part of fusion giants Weather Report between 1971 and 1986. Schooled in Art Blakey’s “hard bop academy,” Shorter then played a significant role as a composer/player in Miles Davis’ Second Great Quintet between 1962 and 1968. His sound is powerful yet elegant.

Texas-born Coleman caused ructions in the jazz world when he arrived in New York in 1959, armed with a plastic alto saxophone with which he unleashed the revolutionary concept of free jazz. Though he liberated jazz both melodically and harmonically, Coleman’s crying alto sound was always steeped in the sound of the blues. His most famous and played composition is "Lonely Woman."

- 13: Jackie McLean (1931–2006)

With its lissom Charlie Parker-influenced inflections, McLean’s sinuous alto saxophone style caught the ear of Miles Davis in 1951, and the trumpet legend included the then-16-year-old saxophonist on his Dig! LP. From 1955, McLean started recording under his own name, impressing as a young exponent of hard bop. As the 50s led into the 60s, McLean began to expand his expressive palette and musical horizons by venturing into more exploratory, avant-garde territory. His legacy remains one of the most important among the world’s best jazz saxophonists.

- 12: Johnny Hodges (1907–1970)

Johnny Hodges made his name in Duke Ellington’s band, which he joined in 1928. His smooth, soulful alto saxophone sound, with its wide, emotive vibrato – which Ellington once claimed “was so beautiful that it brought tears to the eyes” – was featured on a raft of the Duke’s recordings, including “A Prelude To A Kiss.” Both Charlie Parker and John Coltrane were fans.

- 11: Joe Henderson (1937–2001)

Henderson’s tenor sound was unmistakable: loud, robust, and virile. Originally from Ohio, Henderson first made his mark as an exponent of hard bop at Blue Note in the early 60s, and also recorded with Horace Silver (it’s Henderson’s solo you can hear on Silver’s “Song For My Father”). Henderson also added Latin elements to his music and, in the 70s, embarked on a freer, more exploratory mode of jazz.

- 10: Johnny Griffin (1928–2008)

Though diminutive in terms of his physical stature, the Chicago-born Griffin’s prowess on the tenor saxophone earned him the nickname "Little Giant." A major exponent of hard bop, Griffin began his solo career in the 1950s and eventually moved to Europe, where he stayed until his death, but still occasionally toured America 🇺🇸. He was a fearless improviser with an imposing but mobile sound.

- 9: Hank Mobley (1930–1986)

Born in Georgia and raised in New Jersey, Mobley came on the radar of jazz fans in the early 50s as a charter member of The Jazz Messengers, before embarking on a solo career that produced 25 albums for Blue Note. Less belligerent in his attack than Coltrane and Sonny Rollins, though not as smooth or silky as Stan Getz, Mobley’s sonorous, well-rounded tone earned him the title The Middleweight Champion Of The Tenor Saxophone. "Dig Dis" (Remastered 1999/Rudy Van Gelder Edition)

- 7: Coleman Hawkins (1904–1969)

Nicknamed Bean or Hawk, this influential Missouri-born tenor saxophonist was crucial to the development of the saxophone as a viable solo instrument. His 1939 recording of “Body And Soul,” with an extended solo that improvised on, around and beyond the song’s main melody, was a game-changer that opened the door for musicians such as Charlie Parker. Though he was associated with big-band swing, Hawkins played in more of a bop style from the mid-40s onwards. His sound was big, breathy and beefy.

From Woodville, Mississippi, Young – a hipster who spoke in his own “jazz speak” argot – rose to prominence during the swing era of the 30s, playing with Count Basie and Fletcher Henderson. His smooth, mellow tone and airy, lightly flowing style was hugely influential, inspiring tenor players that followed, including Stan Getz, Zoot Sims and Al Cohn. Young is regarded as the Poet Laureate of the tenor sax.

- 5: Dexter Gordon (1923–1990)

Standing at a towering six feet six inches, it was no wonder that this Californian doctor’s son was dubbed Long Tall Dexter. Gordon was the first significant bebop tenor saxophonist and began his recording career in the 40s. Though he could swing with aplomb, Gordon’s forte was ballads, which allowed his rich, emotive tone to convey a poignant lyricism.

- 3: Sonny Rollins (born 1930)

A form of lung disease has silenced Rollins’ tenor saxophone since 2012, but he remains the last great saxophonist of jazz’s golden age. Born Walter Theodore Rollins in New York, his career took off in the 50s and his big, robust sound, combined with his gift for melodic improvisation, gained him the nickname Saxophone Colossus.

Coltrane rewrote the book on tenor saxophone playing and also helped to popularize the soprano version of the instrument. Starting out as a bar-walking blues player, he emerged as the most significant jazz saxophonist after Charlie Parker. Coltrane rose to fame with Miles Davis’ group during the mid-to-late 50s, while enjoying a parallel solo career that eventually produced "A Love Supreme" (recorded 1964/released 1965), one of the most iconic jazz albums of all time. His florid, effusive style was often likened to “sheets of sound.” Coltrane’s music was always evolving and progressed from hard bop through to modal, spiritual jazz, and the avant-garde.

Topping the list of the best jazz saxophonists ever is the man fans referred to simply as Bird. If he had lived beyond 34 years of age, who knows what he could have accomplished. This Kansas City altoist was one of the principal architects of the post-war jazz revolution known as bebop, which emerged in New York in the mid-40s and would shape the trajectory of the genre for years to come. Parker’s ornate style and prodigious technique, which combined melodic fluency with chromatic and harmonic ingenuity, proved profoundly influential. Though he’s been dead for over six decades, no saxophonist yet has eclipsed him in terms of importance.

Non-Afro-American Saxophonists

The following saxophonist rankings and their descriptions by Charles Waring are from UDiscoverMusic.com's "The 50 Best Jazz Saxophonists Of All Time" published on September 13, 2021.

4: Stan Getz (1927-1991) Though originating in Philadelphia, Getz became the pre-eminent tenor saxophonist of the US West Coast cool school scene of the 50s. His alluring, beautifully lyrical tone, combined with his velvet-smooth, effortless style – à la Lester Young – earned him the nickname The Sound. A supremely versatile musician, Getz could play bop, bossa nova (which he helped to take into the US mainstream, not least on the album Getz/Gilberto with its iconic hit “The Girl from Ipanema”) and fusion, and also guested on pop records.

8: Art Pepper (1925-1982) A leading light of the post-war West Coast US jazz scene, Pepper’s rise to stardom began with stints in the bands of Stan Kenton. Like so many jazz musicians that worked in the 50s – including many of the best jazz saxophonists of the era – Pepper’s career was blighted with drug addiction. But even several spells in prison couldn’t taint the lyrical beauty of his distinctive alto saxophone sound, whose roots were in bebop.

27: Paul Desmond (1924-1977) A key member of the Dave Brubeck Quartet between 1951 and 1957 (he wrote the group’s most famous tune, the big crossover hit “Take Five”), this San Francisco-born alto saxophonist’s light delivery helped to define the West Coast cool sound. Amusingly, Desmond once likened his saxophone sound to a dry martini.

32: Gary Bartz (born 1940) From Baltimore, Maryland, Bartz plays both alto and soprano saxophones. Making his recording debut with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers in 1965, he was already recording as a leader for Milestone when Miles Davis recruited him in 1970. Though in the early 70s Bartz’s style gravitated to a more exploratory kind of jazz, his records became smoother and funkier as the decade progressed. He will be remembered among the best jazz saxophonists for being a soulful player who combines flawless technique with emotional depth.

37: Lee Konitz (born 1927) Unique among the best jazz saxophonists to come up in the late 40s and early 50s, Konitz was one of the few altoists who wasn’t infected by Charlie Parker’s bebop sound. Instead, he elected to plow his own distinctive furrow. An ingenious improviser who weaved long, flowing skeins of melody while inserting subtle accent changes, Konitz was initially viewed as a cool school adherent, but in later years explored the avant-garde.

40: Charles Lloyd (born 1938) From Memphis, Tennessee, Lloyd got his first saxophone at the age of nine and, by the 50s, was playing in the touring bands of blues mavens Howlin’ Wolf and B.B. King. A move to LA, in 1956, signaled a change of direction for the saxophonist, who, four years later, ended up replacing Eric Dolphy in Chico Hamilton’s group. Lloyd began his solo career at the same time, and his absorption of rock elements helped his music go down well with a wider audience. Still actively performing today, Lloyd’s music is edgier and more exploratory than it was in the 60s.

43: Joe Lovano (born 1952) The youngest-born entry among the world’s best jazz saxophonists, Ohio-born Lovano can play a clutch of different instruments, though his name is synonymous with the tenor saxophone. The sound he projects is substantial but also athletic and imbued with a heart-tugging soulfulness. Lovano is a supremely versatile musician who has played in a welter of different musical contexts and whose influences range from bop to African music.

44: Jan Garbarek (born 1947) This eminent Norwegian composer and saxophonist (who’s a master of both the tenor and soprano varieties of sax) has enjoyed a long and fecund association with the ECM label, where he’s been since 1970. It was largely through his alliance with Keith Jarrett in the 70s (he played as part of the pianist’s European Quartet) that gained him an international audience. His sound is both lyrical and haunting.

45: Michael Brecker (1949-2007) Hailing from Pennsylvania, Brecker was a tenor saxophonist who was raised on a diet of jazz and rock so that, consequently, he never acknowledged musical boundaries. He played on a raft of pop and rock sessions in the 70s (for everyone from Steely Dan to Art Garfunkel), as well as co-leading the funky Brecker Brothers Band with his younger sibling, Randy. Towards the end of his life, he made records with more a straight-ahead jazz feel.

46: Gerry Mulligan (1927-1996) Mulligan’s resonant baritone sax appeared on countless recording sessions during his long and fertile career, including those by Miles Davis, Billie Holiday, and Dave Brubeck. Mulligan was an astute arranger and skilled innovator too, conceiving a piano-less quartet with Chet Baker, in 1950. He was integral to the more relaxed West Coast cool style.

49. Pepper Adams (1930-1986) Baritone specialist Park “Pepper” Adams came from Michigan and was a stalwart of the Detroit scene, where he played with Donald Byrd in the late 50s and early 60s. An in-demand sideman due to the deep sonorities and dark textures he created on his baritone sax, Adams was an integral member of the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra between 1966 and 1977.

50. Gato Barbieri (1932-2016) With his raw, wailing tenor sax sound, Argentina-born Leandro “Gato” Barbieri plowed a Coltrane-esque avant-garde furrow in the late 60s before making a more accessible form of music that embraced his Latin American roots. From the 70s onwards, Barbieri leaned towards smooth jazz settings for his music, though his brooding tenor saxophone never lost its visceral intensity.

Afro-American Trumpeters from Mid-century

- Red Allen || (1908–1967) || American trumpeter and vocalist 🎺

- Cat Anderson (1916–1981)

- Emmett Berry (1915–1993)

- Buck Clayton (1911–1991)

- Sweets Edison (1915–1999)

- Roy Eldridge (1911–1989) American trumpeter, knicknamed "Little Jazz," known for sophisticated harmonies and tri-tone substitutions, influencer on Dizzy Gilllespie, and one of the most influential musicians of the swing era and a precursor to Bebop.

- Lennie Johnson (1923–1973) US American trumpet player known for his high-note work. He played with Jimmy Tyler at Wally’s Paradise in Boston in the late 1940s. From 1950 on and off trhough 1953 with Sabby Lewis, then with Herb Pomeroy, then in 1959 and early 1960 with Quincy Jones, but rejoining Herb Pomeroy in mid–1960. In February 1961, he replaced Joe Newman in the Count Basie Orchestra for eight months. In the 1960s, he freelanced in various Boston-based groups with other former Pomeroy bandmates. In 1968, he was hired as an instructor at Berklee College of Music in Boston.

- Howard McGhee (1918–1987) One of the first American Bebop jazz trumpeters, along with Dizzy Gillespie, Fats Navarro and Idrees Sulieman, renowned for his fast fingering and high notes, and influencing younger Bebop trumpeters, such as Fats Navarro.

- Ray Nance (1913–1976) An American jazz trumpeter, violinist and singer, best remembered for his long association with Duke Ellington and his orchestra.

- Joe Newman (1922–1992) An American jazz trumpeter, composer, and educator, best known as a musician who worked with Count Basie during two periods.

- Charlie Shavers (1920–1971) An American jazz trumpeter who played with Dizzy Gillespie, Nat King Cole, Roy Eldridge, Johnny Dodds, Jimmie Noone, Sidney Bechet, Midge Williams, Tommy Dorsey, and Billie Holiday. He was also an arranger and composer, and one of his compositions, "Undecided", is a jazz standard.

- Cootie Williams (1911–1985) An American jazz, jump blues, and rhythm and blues trumpeter.

- Clark Terry (1920–2015) American swing and Bebop trumpeter, flugelhornist, composer and educator who played with Charlie Barnet (1947), Count Basie (1948–51), Duke Ellington (1951–59), Quincy Jones (1960), and Oscar Peterson (1964–96). He was with The Tonight Show Band on The Tonight Show from 1962 to 1972. His career in jazz spanned more than 70 years, during which he became one of the most recorded jazz musicians, appearing on over 900 recordings. Terry also mentored Quincy Jones, Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock, Wynton Marsalis, Pat Metheny, Dianne Reeves, and Terri Lyne Carrington.

- Miles Davis (1926–1990) American jazz trumpeter who helped start cool jazz, modal jazz, jazz/rock fusion, and even hip hop jazz.

For example, we do not grant the Navy credit for dumping thousands of military marching band instruments on the docks of New Orleans after the Spanish American War but it is what the locals DID with them that counted. As Martin E. Rosenberg has argued in his first long article, Afro-Americans at the turn of the 20th century experienced time DIFFERENTLY than Americans or Europeans and that is why their music comes out differently. Non-African Americans can learn to experience time that way, but it is a CULTURAL cognitive difference, like Edwin Hutchins has argued about bottom up navigational cognition among Micronesian islanders.

Reasons why jazz DOES NOT remain an exclusively black musical phenomenon

We saw above that jazz began just at the turn of the 20th century in the United States as a cultural musical melange combining Ragtime, blues, Latin music, rhythms influenced by African rhythms, popular tunes, call and response, and even military/brass band influences. Jazz enabled musicians to individually and idiosyncratically express themselves. Jazz musicians hybridized two musical scales (diatonic and pentatonic), improvised and created new melodies, incorporated big-time syncopation, and combined musical instruments in novel combinations.

It is an actual philosophical question regarding whether any phenomenon that originates from one race of people can claim ownership of that phenomenon after new things are added to it by others not of that source race. It is even difficult to figure out exactly what questions and issues this topic area covers. To try to get a better handle on some of the questions consider the origins of rap. Is rap originally an exclusively black musical product. Was rap only done by black musicians?

Merriam-Webster dictionary defines the music genre of rap as “a type of music of African American origin in which rhythmic and usually rhyming speech is chanted to a musical accompaniment.”

So, according to the dictionary credit for the origins of rap started with African Americans. But, was it exclusively African Americans or was it only a majority of African Americans who performed rap music?

Here's a thought experiment that may help support that jazz music's success cannot be entirely attributed to Afro-Americans. Imagine what the jazz scene would be like if in the history of the music no non-Afro-American ever played, performed, and promoted jazz. There would be no Jelly Roll Morton or his Hot Five and Seven recordings, no Sidney Bechet, no Original Dixieland band first easily recognized jazz recording, no Paul Whiteman and his orchestra to promote jazz as a refined musical form, no saxophonist Jack Pettis (1902–1963) who had the first jazz solo on film [17] , no Benny Goodman (the King of Swing) to kick off the Swing revolution in big bands, no Jimmy or Tommy Dorsey to push big band music to prominence on the radio, no Stan Getz and bossa nova, no Chet Baker, no Chick Corea and his fusion band Return to Forever, no John McLaughlin and his Mahavishnu Orchestra, and so forth. Non-Afro-American have contributed to the jazz culture and jazz scene since its inception.

“Count Basie and Benny Goodman, Eddie Lang and Lonnie Johnson, Charlie Parker and Chet Baker, Miles Davis and Bill Evans. "White musicians have brought innovation to jazz," said Tony, "Not as cultural appropriators, but as true collaborators." — "The Color of Jazz: A White Musician's Place in A Black World.”[18] (bold not in original)

“Creoles were able to achieve opportunities in society and wealth that approximated the status and rights of white people. However, when the Spanish took over New Orleans in 1764, Creoles lost their social and economic status, a change that forced them to look for work. Many became traveling musicians, a phenomenon that would evolve into the Southern minstrel show. These Creole musicians and their descendants became the primary inventors of early jazz.Meanwhile, in the 1890’s, the earliest forms of jazz began to emerge in New Orleans, a multiracial and multicultural French-ruled city with a social order that demanded music and revelry. Creole musicians were combining the elements of West African work songs, slave spirituals, minstrel and vaudeville shows, and rural blues expression with the European brass band instruments and harmonies. This newly born hybrid music filled the streets of New Orleans on every occasion from parades to funeral marches.” [19] (bold not in original)

“Musical traditions carried to the New World in the hearts of enslaved West Africans were integrated with European and Latin musical traditions creating new musical forms that are uniquely American. Jazzistry showcases the evolution of America’s music demonstrating the multicultural integration that comprises our culture.”[20] (bold not in original)

Why then do Afro-American get the bulk of the credit for 'inventing' jazz?

Part of the reason may be that of the early perception of jazz being a less than savory music and therefore not something that the dominant white culture even wanted to be associated with.

““In the book, Jazz in Black and White: Race, Culture, and Identity in the Jazz Community, author Charles D. Gerard posed the question, "Is jazz a universal idiom or a black art form?" He also writes that white musicians have been a part of jazz since 1910, but "a series of African-American artists have forged the history of jazz—and the developments have been a result of black people's search for a meaningful identity as Americans and members of the African diaspora." — "The Color of Jazz: A White Musician's Place in A Black World."[21] (bold not in original)

Many types of jazz were from many races

Gypsy jazz:

“Guitarist Django Reinhardt and violinist Stéphane Grapelli created the first major European jazz group when they established the Quintette du Hot Club de France in the late 1930s. With an instrumentation that only featured string instruments, without drums (Reinhardt, Grapelli, two rhythm guitarists and double bass), the Quintette’s softer sound allowed the pair’s virtuosic soloing to be heard clearly. Gypsy jazz remains popular as a sub-genre that is influenced by the American jazz tradition but is very much a unique style, with its own language and repertoire, much of which is composed by Reinhardt. This type of jazz has been continued by more recent musicians including Biréli Lagrène and the Rosenberg Trio.”[22] (bold not in original)

Cool and West Coast jazz:

The cool jazz movement was a coordinated effort by musicians of several races and not predominantly by Afro-Americans. The Afro-Americans initially involved in the album "Birth of the Cool" recorded in 1949–1950 and led by Afro-American Miles Davis, with Caucasians Gil Evans, Wikipedia: Birth of the Cool reports that the music featured “unusual instrumentation and several notable musicians, the music consisted of innovative arrangements influenced by classical music techniques such as polyphony, and marked a major development in post-bebop jazz.” American jazz critic, musician, author, and jazz historian Ted Gioia (b. 1955) goes into more detail as to how this band of musicians developed the sound and its sources included influences from non-African European musical influences:

“[The participants] were developing a range of tools that would change the sound of contemporary music. In their work together, they relied on a rich palette of harmonies, many of them drawn from European impressionist composers. They explored new instrumental textures, preferring to blend the voices of the horns like a choir rather than pit them against each other as the big bands had traditionally done with their thrusting and parrying sections. They brought down the tempos of their music ... they adopted a more lyrical approach to improvisation.”[23] (bold not in original)

Table of non-black male jazz musicians

There have been plenty of non-black (other than Afro-American) jazz musicians, all of whom contributed to the history of jazz everywhere in its history, as seen in the table below of mostly American non-Afro-American jazz musicians. Many different races have been musicians specializing in jazz, so it is too simplistic to claim that jazz is exclusively an Afro-American creation.

The table below leaves out the many contributions from jazz vocalists of any race but see another relevant table below regarding vocalists. For an incomplete list of female jazz musicians, many of whom are non-black, see PoJ.fm's Sp7. Women and Jazz; also see another table below of the non-black Jazz Vocalists from 50 Best All-time.

| Table of Male Non-Afro-American Jazz Musicians | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Musician | Birth–Death dates | Country — Musical Instrument(s) & Roles | |

| Jelly Roll Morton | (1890–1941) | American (New Orleans) pianist 🎹, composer 🎼, arranger, and bandleader. | |

| Paul Whiteman | (1890–1967) | American violinist 🎻, bandleader, composer 🎼, and orchestra director. | |

| Sydney Bechet | (1897–1959) | American (New Orleans) jazz saxophonist 🎷, clarinetist, and composer 🎼. | |

| Tony Parenti | (1900–1972) | American (New Orleans) jazz clarinetist and saxophonist 🎷. | |

| Wingy Manone | (1900–1982) | American (New Orleans) jazz trumpeter 🎺, composer 🎼, singer, and bandleader. | |

| Leon Roppolo | (1902–1943) | American (moved to New Orleans at ten years old) early jazz clarinetist, saxophonist 🎷, guitarist 🎸, and best known for his playing with his fellow New Orleanians in the New Orleans Rhythm Kings (1921–1924) based in Chicago.  (The New Orleans Rhythm Kings in 1922: (left to right) | |

| Santo Pecora | (1902–1984) | American (New Orleans) jazz trombonist. | |

| Bix Biederbecke | (1903–1931) | American jazz cornetist, pianist 🎹 and composer 🎼. | |

| Sharkey Bonano | (1904–1972) | American jazz trumpeter 🎺, band leader, and vocalist. | |

| Frank Teschemacher | (1906–1932) | American jazz clarinetist and alto-saxophonist 🎷, associated with the "Austin High" gang. | |

| Bud Freeman | (1906–1991) | American jazz musician, bandleader, composer 🎼, tenor saxophonist 🎷, and clarinetist. | |

| Benny Goodman | (1909–2006) | American clarinetist and bandleader known as the "King of Swing." | |

| Louis Prima | (1910–1978) | American (New Orleans) jazz singer, songwriter, bandleader, and trumpeter 🎺. | |

| Johnny Richards | (1911–1968) | American jazz arranger and composer, and a principal arranger for Stan Kenton's big band in the 1950s and early 1960s, such as "Cuban Fire!" (1956) and "Kenton's West Side Story." He wrote the music for the popular song "Young at Heart" (1953), made famous by Frank Sinatra (1915–1998) and others. | |

| Stan Kenton | (1911–1979) | American pianist 🎹, composer 🎼, arranger and band leader who led an innovative and forward-looking influential jazz orchestra for almost four decades. A pioneer in the field of jazz education, creating the Stan Kenton Jazz Camp/Clinic in 1959 at Indiana University. By 1975, he was conducting over one hundred clinics a year, as well as four week-long summer clinics on college campuses. | |

| Dave Barbour | (1912–1965) | American jazz guitarist 🎸.

| |

| Gil Evans | (1912–1988) | Canadian pianist 🎹, composer 🎼, and bandleader who worked extensively with Miles Davis. | |

| Woody Herman | (1913–1987) | American jazz clarinetist, saxophonist 🎷, singer, and big band leader. | |

| Dr. M.E. "Gene" Hall | (1913–1993) | American music educator, saxophonist 🎷, and arranger, known for creating and presiding over the first academic curriculum leading to a bachelor's degree in jazz at the University of North Texas College of Music in 1947.  | |

| Bobby Hackett | (1915–1976) | American jazz trumpeter 🎺, cornetist, and guitarist 🎸 with the bands of Glenn Miller (1904–1944) and Benny Goodman (1909–1986) in the late 1930s and early 1940s. | |

| Pete Rugolo | (1915–2011) | American jazz composer, arranger and record producer. | |

| Howard Rumsey | (1917–2015) | American jazz double-bassist known for his leadership of the Lighthouse All-Stars in the 1950s. | |

| Sam Donahue | (1918–1974) | American jazz saxophonist, trumpeter, and musical arranger who performed with Gene Krupa, Tommy Dorsey, Benny Goodman, Billy May, Woody Herman, and Stan Kenton. | |

| Eddie Safranski | (1918–1974) | American jazz double bassist, composer and arranger who worked with Stan Kenton. He also worked with Tony Bennett, Charlie Barnet, Benny Goodman and Bobby Darin. From 1946 to 1953 he won the DownBeat Readers' Poll for best bassist. | |

| Lennie Tristano | (1919–1978) | American jazz pianist, composer, arranger, and teacher of jazz improvisation. | |

| Shelly Manne | (1920–1984) | American jazz drummer 🥁.  | |

| John LaPorta | (1920–2004) | American jazz clarinetist and composer. | |

| Dave Brubeck | (1920–2012) | American jazz pianist 🎹 and composer 🎼, and one of the foremost exponents of cool jazz.  (Paul Desmond on left with Dave Brubeck seated) | |

| Ken Hanna | (1921–1982) | American jazz trumpeter, arranger, composer, and bandleader, best known for his work with Stan Kenton. | |

| Jimmy Giuffre | (1921–2008) | American jazz clarinetist, saxophonist 🎷, composer 🎼, and arranger; best known for encouraging free interplay between the musicians, anticipating forms of free improvisation. | |

| Leon Breeden | (1921–2010) | American clarinetist, composer, and jazz educator. Breeden was the chairman of Jazz Studies and director of the One O'Clock Lab Band at the University of North Texas College of Music from 1959 to 1981. | |

| Chico Hamilton | (1921–2013) | American jazz drummer 🥁 and bandleader. | |

| Bob Whitlock | (1921–2015) | American double bassist. | |

| Serge Chaloff | (1923–1957) | America's greatest Bebop jazz baritone saxophonist 🎷. | |

| Tito Puente | (1923–2000) | American musician, songwriter, bandleader, and record producer of Puerto Rican descent best known for dance-oriented mambo and Latin jazz compositions over a 50-year career. | |

| Paul Desmond | (1924–1977) | American popular cool jazz alto saxophonist 🎷 and composer 🎼, best known for his work with the Dave Brubeck Quartet and for composing that group's biggest hit, "Take Five." | |

| Henry Mancini | (1924–1994) | American composer, conductor, arranger, pianist and flautist. Often cited as one of the greatest composers in the history of film, he won four Academy Awards, a Golden Globe, and twenty Grammy Awards, plus a posthumous Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1995. | |

| Shorty Rogers | (1924–1994) | American jazz trumpeter 🎺, flugelhornist, in demand arranger, and one of the principal creators of West Coast jazz. | |

| Bill Perkins | (1924–2003) | American cool jazz saxophonist and flutist, popular on the West Coast jazz scene, known primarily as a tenor saxophonist. | |

| Louie Belson | (1924–2009) | American jazz drummer 🥁, composer 🎼, arranger, bandleader, educator, & pioneered using two bass drums. | |

| Art Pepper | (1925–1982) | American alto saxophonist 🎷, occasional tenor saxophonist 🎷, and clarinetist, active in West Coast jazz, coming to prominence in Stan Kenton's (1926–1982) big band, and one of the world's greatest altoists. | |

| Zoot Sims | (1925–1985) | American jazz saxophonist 🎷, playing mainly tenor but also alto (and, later, soprano) saxophone, first gaining attention in the "Four Brothers" sax section of Woody Herman's (1913–1987) big band. | |

| Bob Cooper | (1925–1993) | American jazz primarily tenor saxophonist 🎷 and oboist. | |

| Sal Salvador | (1925–1999) | American bebop jazz guitarist and a prominent music educator. | |

| Clem DeRosa | (1925–2011) | American jazz drummer, composer, arranger, band leader, and influential music educator. | |

| Russ Freeman | (1926–2002) | American jazz pianist 🎹. | |

| Herbie Steward | (1926–2003) | American jazz tenor saxophonist 🎷 known as one of the "Four Brothers" in Woody Herman's Second Herd. | |

| Stan Levey | (1926–2005) | American jazz drummer 🥁. | |

| Bud Shank | (1926–2009) | American alto saxophonist 🎷 and flautist. | |

| Terry Gibbs | (b. 1926) | American vibraharpist and band leader. | |

| Stan Getz | (1927–1991) | American jazz tenor saxophonist 🎷 who helped popularize bossa nova in the United States the hit single "The Girl from Ipanema" (1964). He was known as "The Sound" because of his warm, lyrical tone.  (Photo by René Speur) | |

| Gerry Mulligan | (1927–1996) | American jazz baritone saxophonist 🎷, clarinetist, pianist 🎹, composer 🎼 and arranger. | |

| Hank Levy | (1927–2001) | American jazz composer and saxophonist whose works often employed unusual time signatures and best known as a big band composer for Stan Kenton and the Don Ellis Orchestra, as well as the founder and long-time director of Towson University's Jazz Program. | |

| Lee Konitz | (1927–2020) | American composer 🎼 and alto saxophonist 🎷 who played in a wide range of jazz styles, including Bebop, cool jazz, and avant-garde jazz. | |

| Doc Severinson | (b. 1927) | American trumpeter 🎺 and bandleader of "The Tonight Show" with Johnny Carson from 1967–1992. | |

| Bill Holman | (b. 1927) | American saxophonist 🎷, composer 🎼, orchestrator, arranger, conductor, and songwriter.

| |

| Maynard Ferguson | (1928–2006) | Canadian jazz trumpeter and multi-instrumentalist on flugelhorn, Firebird trumpet, trombone, valve trombone, superbone (double trombone), baritone horn, French horn, soprano saxophone and known for his ability to play in high registers. | |

| Bill Evans | (1929–1980) | American jazz pianist 🎹, composer 🎼, and trio bandleader. | |

| Chet Baker | (1929–1988) | American jazz trumpeter 🎺, outstanding vocalist, and innovator in cool jazz. | |

| Bob Brookmeyer | (1929–2011) | American jazz valve trombonist, pianist 🎹, arranger, and composer 🎼. | |

| André Previn | (1929–2019) | German-American pianist 🎹, composer 🎼, arranger, conductor, & celebrated trio pianist, accompanist to singers of standards, and pianist-interpreter of songs from the "Great American Songbook." | |

| Joe Zawinul | (1932–2007) | Austrian jazz pianist 🎹, keyboardist, composer 🎼, and band leader. | |

| Tom Ferguson | (1932–2013) | American jazz pianist and Director of Bands at then Memphis State University (now University of Memphis) from 1962 to the mid-1970s. He later served as Professor of Music and Director of Jazz Studies at Arizona State University. He formed the Tom Ferguson Trio with bassist Bob Badgely and drummer Carmen Castaldi. | |

| Dan Haerle | (b. 1937)) | American jazz pianist, composer, author and teacher, based in Denton, Texas and professor emeritus of Jazz Studies at the University of North Texas. | |

| Bob James | (b. 1939) | American keyboardist, arranger, record producer, and founder of the American smooth jazz quartet Fourplay.. | |

| Mike Vax | (b. 1940) | American jazz trumpeter and jazz educator. | |

| Chick Corea | (1941–2021) | American pianist 🎹, keyboardist, percussionist, composer 🎼, bandleader, and pioneer in jazz fusion. | |