Sp7. Women and Jazz

Contents

- 1 Discussion

- 2 Quotations

- 3 Introduction

- 4 Jazz women 1910–1920s America

- 5 Jazz women in 1930's America

- 6 Jazz women in 1940's America

- 7 Jazz women in 1950's America

- 8 Jazz women in 1960's America

- 9 Jazz women in 1970's America

- 10 Jazz women in 1980's America

- 11 Jazz women in 1990's America

- 12 Jazz women in the 20th century

- 13 Jazz women in 21st Century

- 14 Musician's Biography Websites

- 15 Internet & Bibliographic Resources on Women in Jazz

- 16 NOTES

Discussion[edit]

Quotations[edit]

“Leonard Feather, a fellow expatriate from England, and well-known figure in the jazz world as a critic, composer, and record producer, had by then begun tracking Marian McPartland's career, carefully and with a certain concern. Writing in Downbeat in 1952, he drily, but bluntly, summed up Marian's position in jazz: "She is English, white, and a woman—three hopeless strikes against her."”[1] (bold not in original)

“"Only God can make a tree," the swing historian George T. Simon wrote in The Big Bands (London: Macmillan, 1967), "and only men can play good jazz."[2] (bold not in original)

“In addition to unfair pay scales, jazz women encountered equally hostile philosophical and sexist attitudes. An unsigned Down Beat article of 1938 illustrates one particularly potent masculine point of view:

- Why is it that outside of a few sepia females, the woman musician never was born capable of sending anyone further than the nearest exit? It would seem that even though women are the weaker sex they would be able to bring more out of a poor, defenseless horn than something that sounds like a cry for help. You can forgive them for lacking guts in their playing but even women should be able to play with feeling and expression and they never do it. ("Why Women Musicians are Inferior" 1938)

Both the anonymity of this tirade and the willingness of Down Beat to publish it reveal a latent yet permeating sexism. The explicitly masculinist and racialized tone of this passage represents one particularly prevalent political ideology. Here, women are defined as physically inferior, yet are somehow expected to have greater expressive and emotional capacities. Further, the anonymous author promulgates racial stereotypes by admitting a few black (sepia) female musicians into the masculine institution of jazz.”[3] (bold and bold italic not in original)

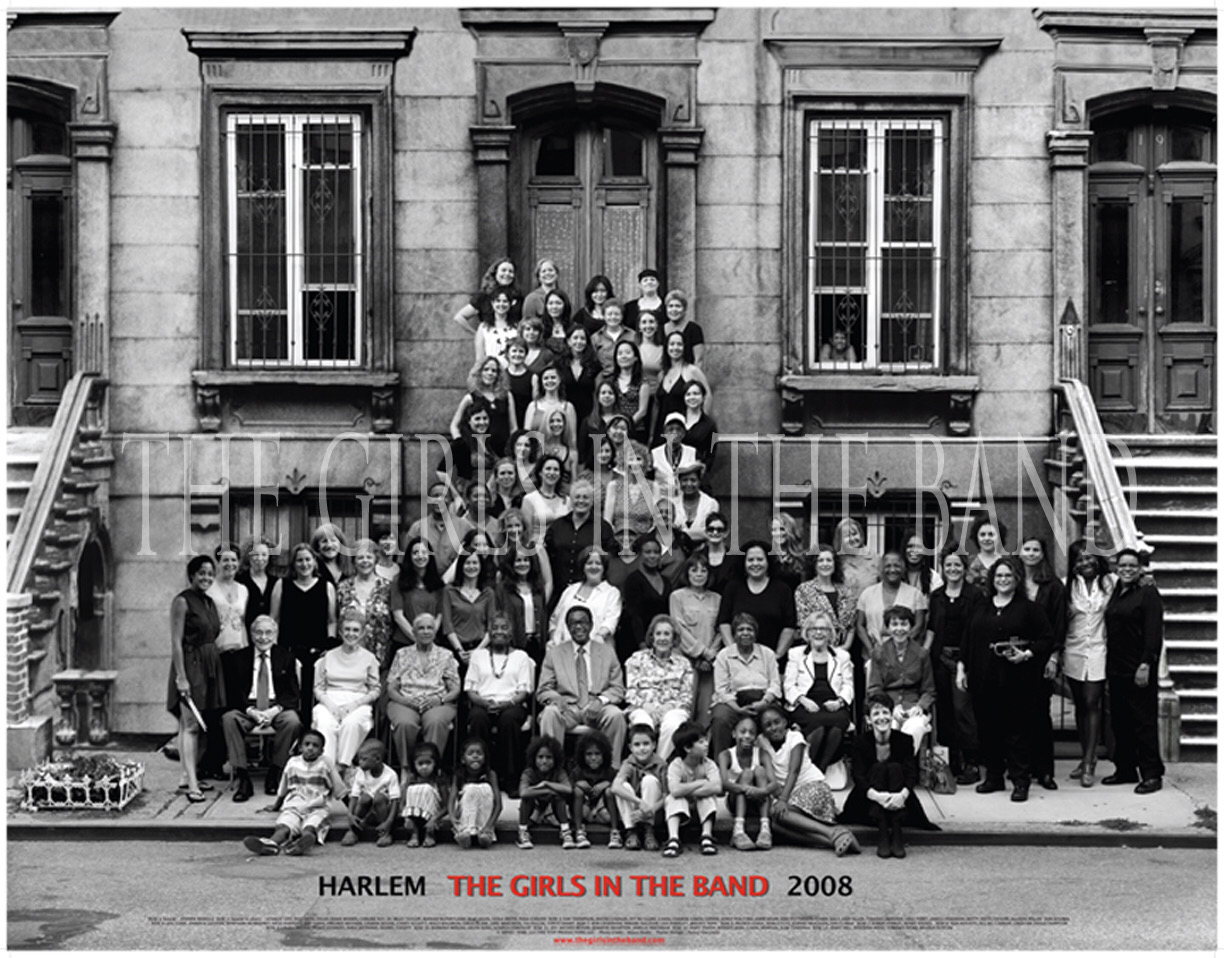

Colorized group shot for Director Judy Chaikin's documentary "The Girls in the Band" (picture modeled after Art Kane's Esquire magazine (now colorized) photograph "A Great Day in Harlem" taken in 1958).

Original black and white group shot for Director Judy Chaikin's documentary "The Girls in the Band" (picture modeled after Art Kane's Esquire magazine photograph "A Great Day in Harlem" taken in 1958).  Chaikin's documentary tells the true stories of female jazz musicians enduring sexism, racism, and lack of opportunities all so they could play their music.

Chaikin's documentary tells the true stories of female jazz musicians enduring sexism, racism, and lack of opportunities all so they could play their music.

Introduction[edit]

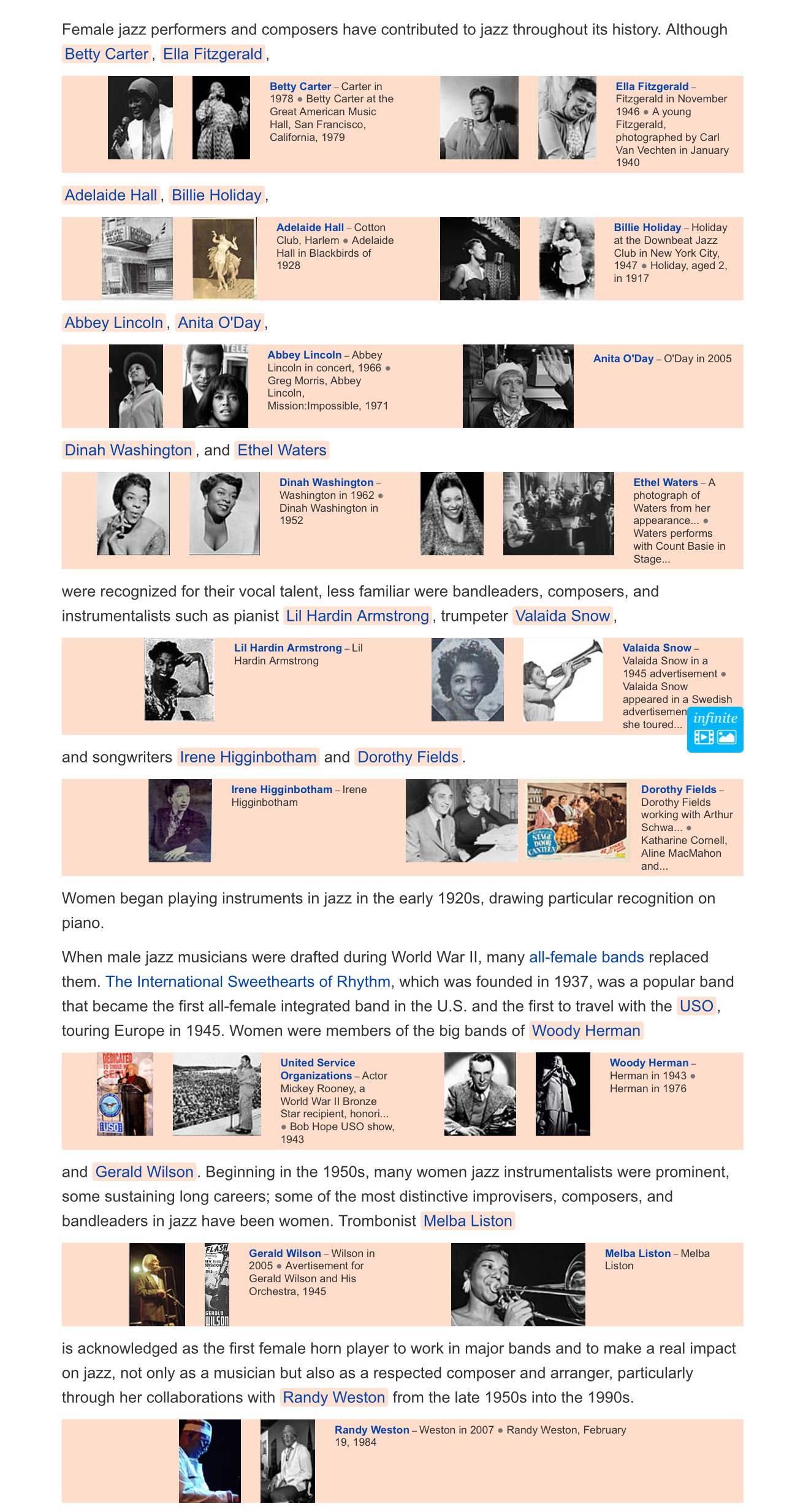

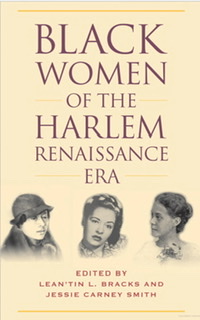

Women have probably been underrepresented in every professional field with few non-gendered exceptions. For how this has affected women philosophers generally, see Rebecca Buxton and Lisa Whiting's essay "Women or Philosophers" (February 4, 2021) and Helen Beebee's article "Women in Philosophy: What's Changed?" (May 29, 2021) both at The Philosophers' Magazine. To see what has been adopted to assist UK philosophy departments, learned societies and journals in ensuring that they have policies and procedures in place that encourage the representation of women in philosophy, see "Good Practice Scheme." For women's representations in philosophy classrooms and faculty offices, see "The Diversity of Philosophy Students and Faculty in the United States," (May 30, 2021) by Eric Schwitzgebel, Liam Kofi Bright, Carolyn Dicey Jennings, Morgan Thompson and Eric Winsberg.

Established jazz author Ted Gioia (b. 1957) in his third edition of The History of Jazz (2021) points out how women instrumentalists have often struggled to make it in an overly patriarchal jazz community.

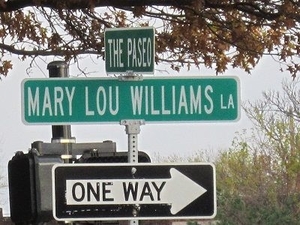

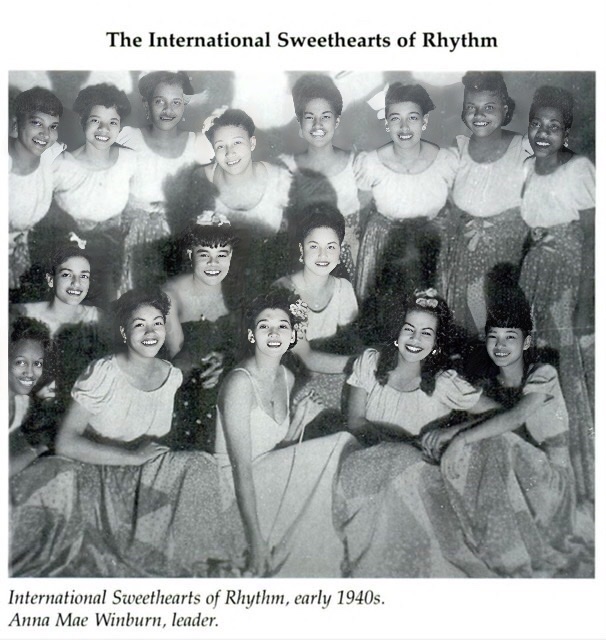

“Women had long been accepted as vocalists in popular music, but few had enjoyed successful careers as jazz instrumentalists, and even fewer managed to make records during this period. Surviving news coverage attests that female bands were well known during the 1930s, and we hear mention of the Harlem Playgirls, the Darlings of Rhythm, the Hip Chicks, Dixie Sweethearts, and other ensembles, but we have little documentation of the music they made. But in 1937, the International Sweethearts of Rhythm, an all-female swing band, was formed—initially as a fund-raising project at the Piney Woods Country Life School for poor and orphaned African American children in Mississippi. But the band members had larger ambitions and, after a well-received debut at the Howard Theater, would go on to tour the United States and Europe, as well as record for the Victor label. The ensemble was often marketed for its glamour, and this may have led some to overlook its high musical standards, as demonstrated on tracks such as “Swing Shift” and “Bugle Call Rag.” But Louis Armstrong was so impressed with trumpeter Ernestine “Tiny” Davis that he offered her a job at a substantial pay raise, which she declined, and the propulsive drummer Pauline Braddy, billed as “Queen of the Drums,” was a major talent by any measure. The International Sweethearts of Rhythm not only helped establish women as respected instrumentalists, but also broke down barriers as the first integrated female band in the United States. Yet their example would stand out as a rare exception, and only gradually gain the interest of critics and music historians. A turning point came in 1980, when pianist and broadcaster Marian McPartland worked with the Kansas City Jazz Festival to sponsor a reunion and public event honoring nine surviving band members. Williams, for her part, gradually rose through the ranks of the Kirk organization: for a time she acted as chauffeur for the band (she also worked as a hearse driver during this period), eventually securing a spot as a staff writer and full-time performer. But from 1930 until 1942, Williams served as the main catalyst for the Kirk ensemble. Her charts, such as “Mary’s Idea” and “Walkin’ and Swingin’,” were marked by a happy mixture of experimentalism and rhythmic urgency, while her playing soon earned her star billing as “The Lady Who Swings the Band.” In later years, Williams’s progressive tendencies became even more pronounced, leading her to adopt much of the bebop vocabulary and inspiring her to compose extended pieces, most notably the Zodiac Suite from 1945. Following her conversion to Catholicism in the 1950s, Williams wrote and performed a number of sacred works and continued to expand her musical horizons long after the age when most artists settle comfortably into a familiar style and repertoire. Her 1962 work for voices “Black Christ of the Andes” is a neglected masterpiece that makes clear that Williams could have reached the highest rung as a choral composer, and fifteen years later this stalwart of traditional jazz went head-to-head with free-jazz titan Cecil Taylor in a controversial Carnegie Hall concert. At this high-profile performance, held four years before Williams’s death in 1981, two confident masters of the jazz keyboard confronted each other head on, and neither side blinked. As such daring gestures made clear, 'none of the Kansas City pioneers brought a broader perspective to their music making than Mary Lou Williams.”[4] (bold not in original)

In her "Women in Jazz 1920s–1950," a term paper in 2015 for her "History of American Music" course, author Emma Lamoreaux explains that women are underrepresented in jazz history for multiple reasons. First, there was significant and repressive male prejudice against all non-male musicians. Second, jazz had a social stigma of being sleazy and sexy, allegedly inappropriate for female participation since people judged it socially unacceptable for women to participate in such activity. A third and strikingly telling reason accounting for women's underrepresented in jazz history is from an over-reliance on recordings. Female jazz musicians were underrepresented in recordings precisely because of the first two prejudices against their playing jazz in the first place.

Women jazz musicians have almost always been in a discouraging situation caused by numerous factors against them: male gender prejudices against female musicians, the belief by many that there are no good female jazz players (although this has always been false), that playing anything other than the piano or singing was not 'lady-like' and was inappropriate for women to play the trumpet, the saxophone, the bass, or the drums.

Several newspaper reporters have written about the problems for women entering into the jazz field, including Robert Palmer (1945–1997) in his January 21, 1977 New York Times article "Women Who Make Jazz" and Peter Watrous in his November 27, 1994 New York Times article JAZZ VIEW: "Why Women Remain At the Back of the Bus."

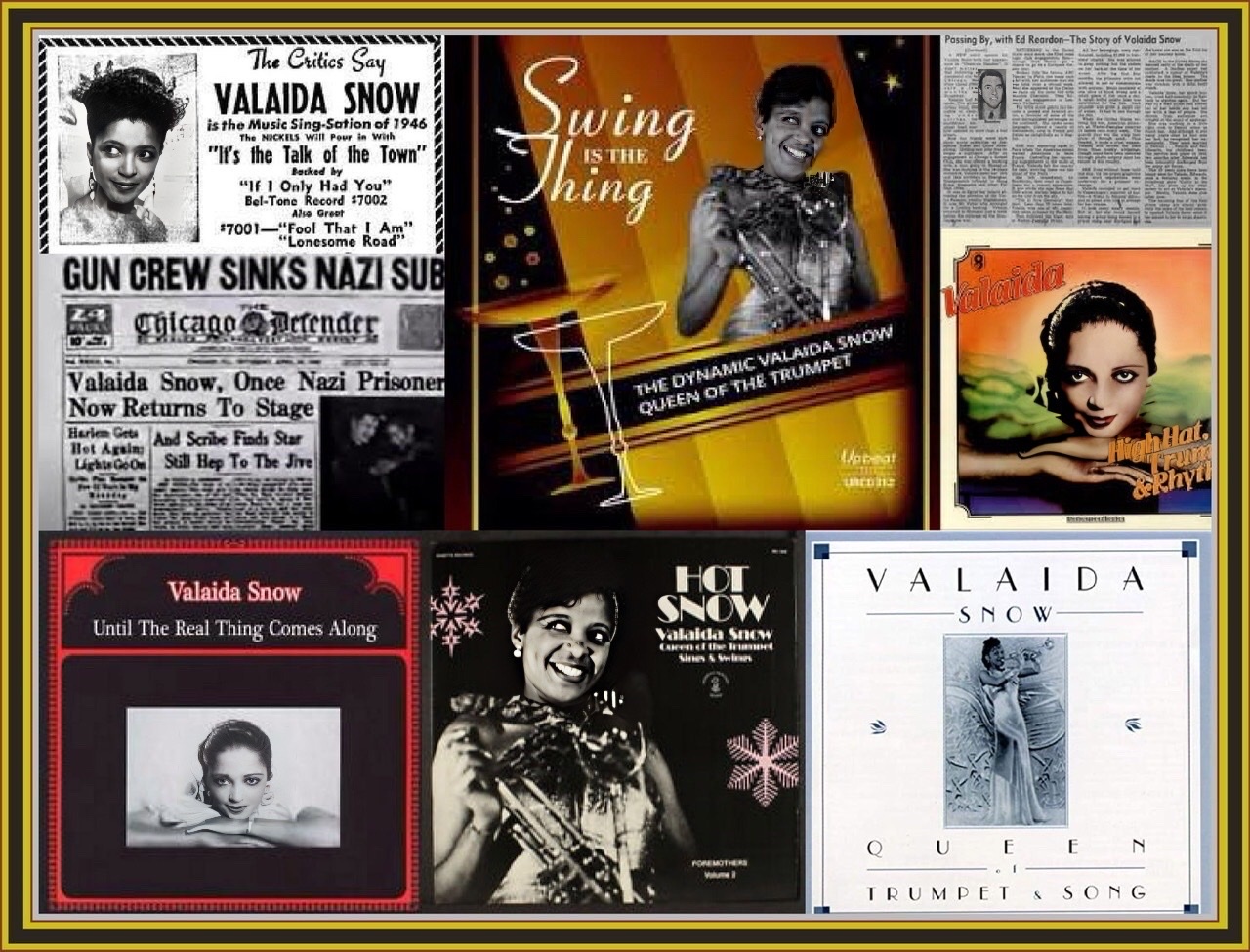

Lamoreaux, in her paper, discusses multilingual composer, instrumentalist, singer, and dancer Valaida Snow (1904–1956). Often known as the “Queen of Trumpet,” Snow recorded her album "Hot Snow," containing both her singing as well as playing her trumpet. By the age of 15, she had learned to play the cello, bass, banjo, violin, mandolin, harp, accordion, clarinet, trumpet, and saxophone. Louis Armstrong thought so highly of her trumpet playing that he said she was the world's second-best jazz trumpet player besides himself. Because of this, she was named "Little Louis" after Louis Armstrong.

A more well-known and influential woman musician was singer, songwriter, electric guitarist, and recording artist Sister Rosetta Tharpe (1915–1973), who was not really a jazz musician but more of a hot gospel performer with her electric guitar playing using heavy distortion and influencing 1960's British electric blues guitar players, such as Eric Clapton and Keith Richards. Wikipedia: Sister Rosetta Tharpe notes that “She attained popularity in the 1930s and 1940s with her gospel recordings, characterized by a unique mixture of spiritual lyrics and rhythmic accompaniment that was a precursor of rock and roll. She was the first great recording star of gospel music and among the first gospel musicians to appeal to rhythm-and-blues and rock-and-roll audiences, later being referred to as "the original soul sister" and "the Godmother of rock and roll."”

Another unsung woman of jazz was Dorothy Donegan (1922–1998), an American jazz pianist and vocalist, working primarily in the stride piano and boogie-woogie style, but she also could play Bebop, swing jazz, or even classical music.

The International Sweethearts of Rhythm was an all-female jazz orchestra in the 1940s that toured widely, including traveling and performing in many venues.

Irene Schweizer

Jolle Leandre

European ones like Barbara Thompson and Marilyn Mazur

Above all, however, they looked to Jutta Hipp, who had already proven in the early 1950s that a musician could be taken seriously as a woman at the instrument even without the "exotic bonus."

There were only three female musicians in Cologne, Germany's WDR big band in 2018. Australian-born trombonist Shannon Barnett became a full member in January, 2014. See and hear her killer trombone solo at 2:12 in on a Paquito D'Rivera date with the WDR Cologne big band.

Karolina Strassmayer alto saxophonist. Since 2004 she has been the first woman to be a permanent member of the WDR Big Band Cologne. In 2004, Strassmayer was also named "Top Five Alto Saxophonist" of the year by the American jazz magazine Downbeat. She played alto sax on Joe Lovano's 20th album "Symphonica" released in 2009 on Blue Note Records from a November 26, 2005 live recording.

Drummer Eva Klesse (b. 1986) became the first female instrumentalist to be appointed professor of jazz at Hochschule für Musik, Theater and Medien in Hannover, Germany (2018).

See below for more facts about these individuals and groups.

NOTE: Screencapture below of women in jazz from WikiVisually: Jazz under topic heading of 2. Elements and Issues of 2.4 Roles of women. Click on any hyperlink, including the photo itself, to go there, then scroll down, or click here and go directly.

(Rosetta Reitz (1924–2008)

Photo by Jill Lynne, 1977)

🌕 Rosetta Reitz (1924–2008) championed women's jazz.

🌕 See Douglas Martin's obituary "Rosetta Reitz, Champion of Jazz Women, Dies at 84," NYTimes, November 14, 2008.

Jazz women 1910–1920s America[edit]

Bertha Gonsoulin[edit]

|

Bertha Gonsoulin (1890–1951)

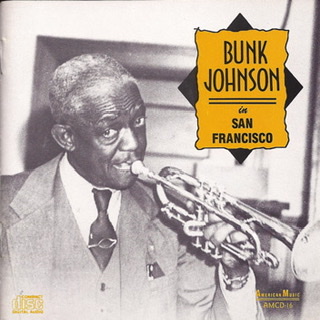

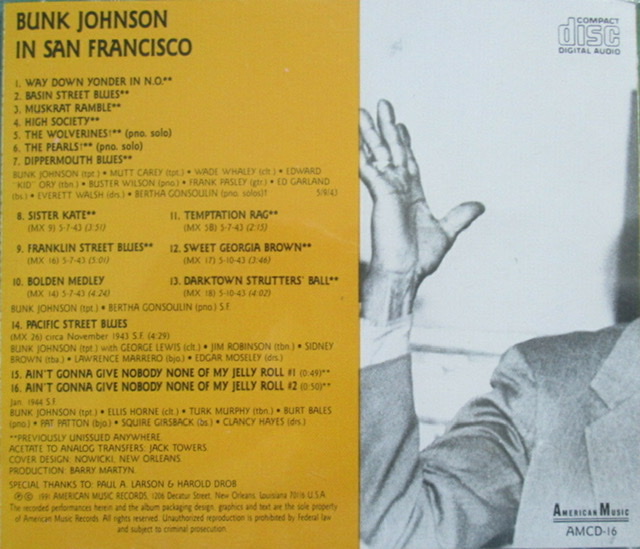

(Bunk Johnson played a concert a week at the Geary Theatre in San Francisco, starting in May 1943 and recruited from Los Angeles players who were sympathetic to his aims. Pictured l. to r. Everett Walsh drums, Buster Wilson piano, Ed Garland bass, Bertha Gonsoulin piano, Frank Pasley guitar, Kid Ory trombone, Bunk Johnson trumpet.) (Source: Black Beauty White Heat)

“At some point in the early nineteen twenties, either before her departure to Chicago with Oliver, or after her return, she took some lessons from Jelly Roll Morton. Bill Colburn told William Russell that Bertha “couldn't go to the places where [Morton] played, so he went to her home [in San Francisco] to teach her. She said he taught her several of his compositions, including "Kansas City Stomp," "The Pearls," and "Frog-i-more."[6] (bold not in original)

“It is interesting to hear Ory a year before he started to officially make a comeback, although the best music is actually provided by pianist Bertha Gonsoulin who is featured on "Wolverine Blues" and "The Pearls." . . . Much better are six duets that Bunk had with Gonsoulin two days before, and one day after, the concert.” (bold not in original)

|

Dr. Sherrie Tucker (University of Kansas) reports on Gonsoulin's jazz career in her well-researched article "A Feminist Perspective on New Orleans Jazz Women," a project for the NOJNHP (New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park) Research Study.

“Cornetist and band leader Joe “King” Oliver moved from New Orleans to Chicago around 1918 or 1919. His first Chicago jobs were in Bill Johnson‟s Royal Gardens band and Lawrence Duhe's Dreamland Café band, but by the fall of 1919, he was leading the band at the Dreamland. The band included Honore Dutrey, Johnny Dodds, Ed Garland, Minor Hall, and a recent migrant from Tennessee, pianist Lil Hardin. Business, however, was rocky at the Dreamland. According to Gene Anderson, rumors that the club might be sold were circulating, and so Oliver decided to seize the opportunity for a California tour for which he had been recommended by trombonist Kid Ory. The band opened at Pergola, a dance hall in San Francisco in June, 1921. (p. 265)“According to Burton W. Peretti, "For New Orleans jazz musicians before 1917, distant California was as important a market as Chicago." Indeed many New Orleans musicians, including Jelly Roll Morton and Kid Ory had moved their career bases to the West Coast as early as musicians in the more often-noted Chicago migration. We know little about Gonsoulin's role in this movement. She is not mentioned in Tom Stoddard's history of jazz in San Francisco, Jazz on the Barbary Coast (Chigwell, Essex: Storyville, 1982). The details of her life are as scarcely considered by most Oliver scholars as the minutia about other members is actively debated. We do know that her nickname was “Bob” or “Miss Bob.” (p. 266)

“We also know that Gonsoulin stuck it out through the year of personnel changes and fickle employment. At one point, a reconfigured band called, “King Oliver's and Ory's Celebrated Creole Orchestra,” made up of Oliver, Kid Ory, Baby Dodds, Ed Garland, Johnny Dodds, and Bertha Gonsoulin, played for Mardi Gras Ball in Oakland. When Oliver brought his band back to Chicago in June, 1922, Gonsoulin was still the pianist. It was she, in fact, not Hardin, who was the working pianist in the Creole Jazz Band when Oliver sent away for a young New Orleans musician by the name of Louis Armstrong to join as second cornet. As Gonsoulin told William Russell in 1940, “the telegram asking Louis Armstrong to join the Oliver band was sent to him on a Saturday evening and he replied Sunday evening. Louis arrived on Tuesday evening, carrying his cornet wrapped in a black bag.” Oliver took Armstrong to the Dreamland to meet Lil Hardin, and to try and convince Lil to come back to his band at the Royal Garden.

“When [Louis] Armstrong joined the band in August 1922, he did so as a part of a larger reorganization of the Creole Jazz Band, which included more shifting of personnel, such as the return of clarinetist Honore Dutrey and pianist Lil Hardin. When Hardin agreed to re-join the band in December 1922, Bertha Gonsoulin was sent back to San Francisco. As an out-of-towner, Gonsoulin recalled that she had been paid in cash the whole time she was in Chicago, and had amassed so much of it that she “carried it home in a pillow case.” At some point in the early twenties, either before her departure to Chicago with Oliver, or after her return, she took some lessons from Jelly Roll Morton. Bill Colburn told William Russell that Bertha “couldn't go to the places where [Morton] played, so he went to her home to teach her. She said he taught her several of his compositions, including "Kansas City Stomp," "the Pearls," and "Frog-i-more." (p. 267)

“What happened to Gonsoulin over the next twenty years is, again, sketchy. The 1930 Census lists a Bertha Gonsoulin, age 49, “wife,” living in Louisiana. This could very well be her. [NOTE: In 1930, Bertha was exactly forty years old.] The age could be right, but by 1940, we find her again in San Francisco. Perhaps she could have moved back and forth between the two cities. We know from a photo and caption in the Chicago Defender, that, in 1940, she was a well-respected piano teacher at the Booker T. Washington Community Service Center in San Francisco. The paper ran a photograph of her looking very distinguished in a white dress, regal gaze, sitting at a piano, not as an entertainer, but as a “Trainer of Musicians.” The caption stated that “Miss Bertha Gonsoulin . . . has the enviable reputation of being one of the finest instructors, composers, and trainers of aspiring musicians in the west.”

“The second [chance to play with Bunk Johnson] came over twenty years later when her [Bertha Gonsoulin] credentials as an Oliver alumnus brought her to the attention of Rudi Blesh and other movers and shakers of the New Orleans Revival. These enthusiasts of early jazz sought Gonsoulin's services as an appropriate accompanist for New Orleans trumpet legend, Bunk Johnson, in 1943.

“Accounts of the 1943 Bunk Johnson concerts and recordings make no mention of her reputation as a “fine instructor,” or “composer,” but they do suggest that she had become “immersed in church music when she was approached by Rudi Blesh to accompany Bunk on the piano.” Martin Williams adds that she had, in fact, “given up jazz for church music” and “had to be persuaded” to play with Bunk Johnson. Whether or not Gonsoulin herself found church music incompatible with jazz—(had she “given up” jazz, or had she not had opportunities to work as a jazz pianist?)—over the next several months, she played a role in the celebration of New Orleans jazz (pre-1929) that became known as the New Orleans Revival. (p. 268)

“In San Francisco in the 1940s, the New Orleans Revival centered around Lu Watters's Yerba Buena Jazz Band, a contemporary group of white male musicians who were inspired by the music of “King” Oliver. Christopher Hillman wrote of the atmosphere of excitement, when, “[I]n early 1943, Rudi Blesh, who was on the fringe of the movement associated with the book Jazzmen, arranged to give a series of lectures on New Orleans jazz at the Museum of Art in San Francisco.” Concerts by “authentic” New Orleans jazz musicians were conceived as part of this popular lecture series. Blesh and other collectors raised money to bring Bunk Johnson appear at one of the lectures, but they had to find musicians to play with him. Blesh located “Bertha Gonsoulin, a lady who had once played with King Oliver in Chicago, but was by then heavily involved in church music.” She agreed to accompany Johnson on the piano.

“The lecture/concert (April 11, 1943) was an enormous success. In his opening remarks, Blesh shared a letter from Louis Armstrong that praised Bunk's genius, and put in a good word for “Miss “Bob” (Bertha Gonsoulin), expressing hopes that they “could get together for a jam session in the near future.” A list of the numbers played by Johnson and Gonsoulin, compiled by Mike Hazeldine and Barry Martyn, includes “Maple Leaf Rag,” “Down by the Riverside,” “High Society,” “Careless Love,” “Pallet on the Floor,” “Tiger Rag,” and “Yes, Lord, I'm Crippled.” The concert was recorded, and several of the numbers are currently available on CD (AMCD-016 "Bunk Johnson in San Francisco"). This event was so well received, that a subsequent one was planned for May 9, 1943 at the Geary Theater.” (p. 269)

“On May 7, 1943, Johnson and Gonsoulin met at the latter musician's home on 1782 Sutter Street in San Francisco to prepare for the forthcoming concert. William Russell, who had just arrived from New Orleans, was on-hand to document the session, which, he later recalled, had not been planned as a recording session, but rather as a chance “to get Bunk's lip in shape.” This rehearsal, however, was, in fact, issued on the American Music label, and is also represented on the aforementioned CD (AMCD- 016 "Bunk Johnson in San Francisco"). The May 9th concert little resembled this intimate rehearsal. It did not include duets between Johnson and Gonsoulin. Trombonist Kid Ory and his band had been brought up from Los Angeles, and the concert primarily featured Johnson with Kid Ory's band. Gonsoulin, who would have known Ory from 1920s concerts with King Oliver, was not much featured, but did play a couple of solos. The next day, she expressed disappointment when she found that her own contributions in the concert were “hardly mentioned in the press.” Perhaps in response to her ennui, Russell recorded Gonsoulin re-creating the solo rendition of “The Pearls” she had performed the previous night. This, too, appears on "Bunk Johnson in San Francisco."

“After the Geary Theater concert, several traditional jazz concerts were presented at the CIO, co-sponsored by a coalition of jazz fans and labor union figures, including Harry Bridges. Bunk Johnson and Bertha Gonsoulin were the “special guests” at the first such concert on July 11, 1943. After Johnson left the San Francisco Bay Area for lack of work, Gonsoulin made at least one further appearance at the CIO, in the spring of 1944.

“At some point, Russell interviewed Gonsoulin, and his hand-written notes are housed at The Williams Research Center. I have drawn heavily from these notes, as one of the few sources of information on Gonsoulin, but must add that these notes are sketchy, focus entirely on her year with King Oliver, and include her claim to have been the pianist on the Gennett session of “The Chimes,” which is incorrect. (p. 270)

“Future research should continue to seek information on Bertha Gonsoulin for years other than 1921–22 and 1943–44. Future research should also explore the possibility that Gonsoulin may have been thinking of a different recording session, other than her discredited claim to have been on the Gennett session, when she told Russell she recorded with Oliver.”[12] (bold not in original)

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

- Armstrong, Lillian Hardin, Oral History, July 1, 1959, Reel I [of I]–Digest–Retyped, Hogan Jazz Archive, Tulane University.

- Russell, William. "Bertha Gonsoulin,1940s," handwritten notes from “California Notes”, MSS 536 F15. The Williams Research Center.

- Russell, William Russell, Oral History digest, Reel I, Feb. 2, 1975, 2, Hogan Jazz Archive, Tulane University

Secondary Sources:

- Anderson, Gene. "The Genesis of King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band." American Music 12.3: 238 (21).

- Dahl, Linda. Stormy Weather: The Music and Lives of a Century of Jazzwomen (New York: Limelight Editions, 1989), 23.

- Handy, D. Antoinette. Black Women in American Bands and Orchestras, Second Edition. Lantham, Mass. and Kent: Scarecrow Press, 1998, 223.

- Hazeldine, Mike, and Barry Martyn, Bunk Johnson: Song of the Wanderer (New Orleans: Jazzology Press, 2000). For more information on these recordings, see http://www.weigts.scarlet.nl/430510.htm

- William Russell, "Bertha Gonsoulin 1940s," handwritten notes from “California Notes”, MSS 536 F15. William Russell Collection, The Williams Research Center.

- Hillman, Christopher. Bunk Johnson: His Life & Times (New York: Universe Books, 1988.

- Peretti, Burton W. The Creation of Jazz: Music, Race, and Culture in Urban America. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1992.

- Placksin, Sally. Jazzwomen: 1900 to the Present, Their Words, Lives and Music (London and Sydney: Pluto Press, 1985), 44.

- Rose, Al, and Edmond Souchon. New Orleans Jazz: A Family Album. Revised edition. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press.

- Russell, William. “Oh, Mister Jelly” A Jelly Roll Morton Scrapbook (Denmark: JazzMedia Aps, 1999).

- "Trainer of Musicians." Chicago Defender, February 3 1940: 9. Photo and caption of Miss Bertha Gonsoulin, piano teacher at Booker T. Washington Community Service Center, San Francisco.

- Williams, Martin. Jazz Masters of New Orleans. New York: MacMillan, 1967, 235, 238.

- AMCD-016 "Bunk Johnson in San Francisco" (These are the recordings from the museum concert, the rehearsal at Gonsoulin's home, and the final intimate session at Gonsoulin's home the day after the Geary Theater concert).

Hal Smith, "Bunk Johnson," The San Francisco Traditional Jazz Foundation Collection: The Charles N. Huggins Project,

Bunk’s first engagement in San Francisco was a concert at the War Veterans Memorial Building, where he played, accompanied by former King Oliver pianist Bertha Gonsoulin. He talked about his early career and generally held the audience in the palm of his hand. This successful event was followed by a concert at the Museum of Modern Art.

Next, jazz impresario Rudi Blesh invited Bunk to perform in his “This Is Jazz” concert series at the Geary Theater. This ambitious presentation was to include Kid Ory, Mutt Carey and members of Ory’s band as backing.

At the Geary Theatre (1943). (L-R) Kid Ory tmb, Wade Whaley cl, Mutt Carey tpt, Bunk Johnson tpt, Everett Walsh drm, Frank Pasley gt, Ed Garland b, Buster Wilson p. Source: Louisiana State Museum Jazz Collection.

Bunk Johnson’s Geary Theatre concert in San Francisco included musicians from Los Angeles players who were sympathetic to his goals. (L-R) Everett Walsh drm (Holding a picture of Lu Watters), Buster Wilson p, Ed Garland b, Bertha Gonsoulin p (Replaced Lil Hardin in King Oliver’s Band in 1921), Frank Pasley gt, Kid Ory tmb and Bunk Johnson tpt. Source: Claes Ringqvist - The Swedish Bunk Johnson Society

"Bunk Johnson in San Francisco" CD American Music AMCD – 16 includes the 1943 concert at the Geary Theater with Kid Ory’s band, duets with pianist Bertha Gonsoulin, Bunk playing along with a George Lewis record and two fragments of unreleased sides from the 1944 sessions.

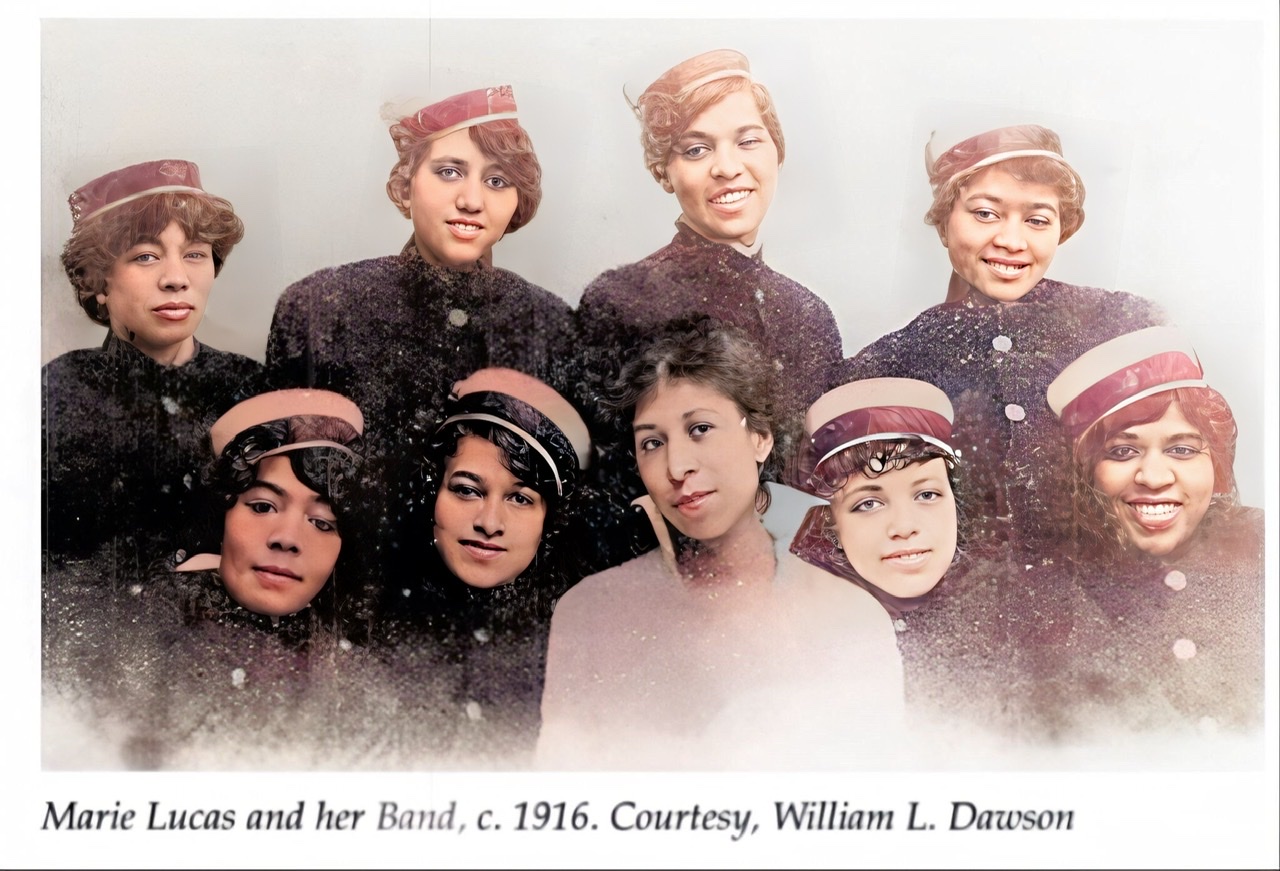

Marie Lucas[edit]

“ . . . her groups also played regularly at theaters in Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. Like the male musicians, the women moved from one group to another. The most active women on the East Coast during this period included, in addition to Anderson and Lucas, Alice Calloway (drums), Mildred Franklin (violin), Pearl Gison (cornet), Leora Meaux (cornet), Mamie Mullen (piano), Olivia Porter (string bass), Ruth Reed (cornet), Maud Shelton (violin), Nellie Shelton (string bass), Eva Sinton (violin), Della Sutton (trombone), and Florence Washington (drums). Trombonist Mazie Mullins played with both male and female bands.”[16]

“According to Snowden, Marie Lucas's band [male] would come out into the pit, and she had sent down to Cuba or wherever it was [Ellington said Puerto Rico] and got all those musicians like trombonist Juan Tizol (1900–1984) and bassist and tubist Ralph Escudero (1898–1970) and had enlarged her band. They would play the show, and we'd [Louis Thomas's Band] come back and play the intermission and exit music (Stanley Dance, The World of Swing, p. 47). In his book Music Is My Mistress Ellington indicated that a group under Lucas's direction played the TOBA circuit as well as the Howard Theatre. He indicated that the group was very impressive "because all the musicians doubled on different instruments, something that was extraordinary in those days" (p. 34).”[15]

|

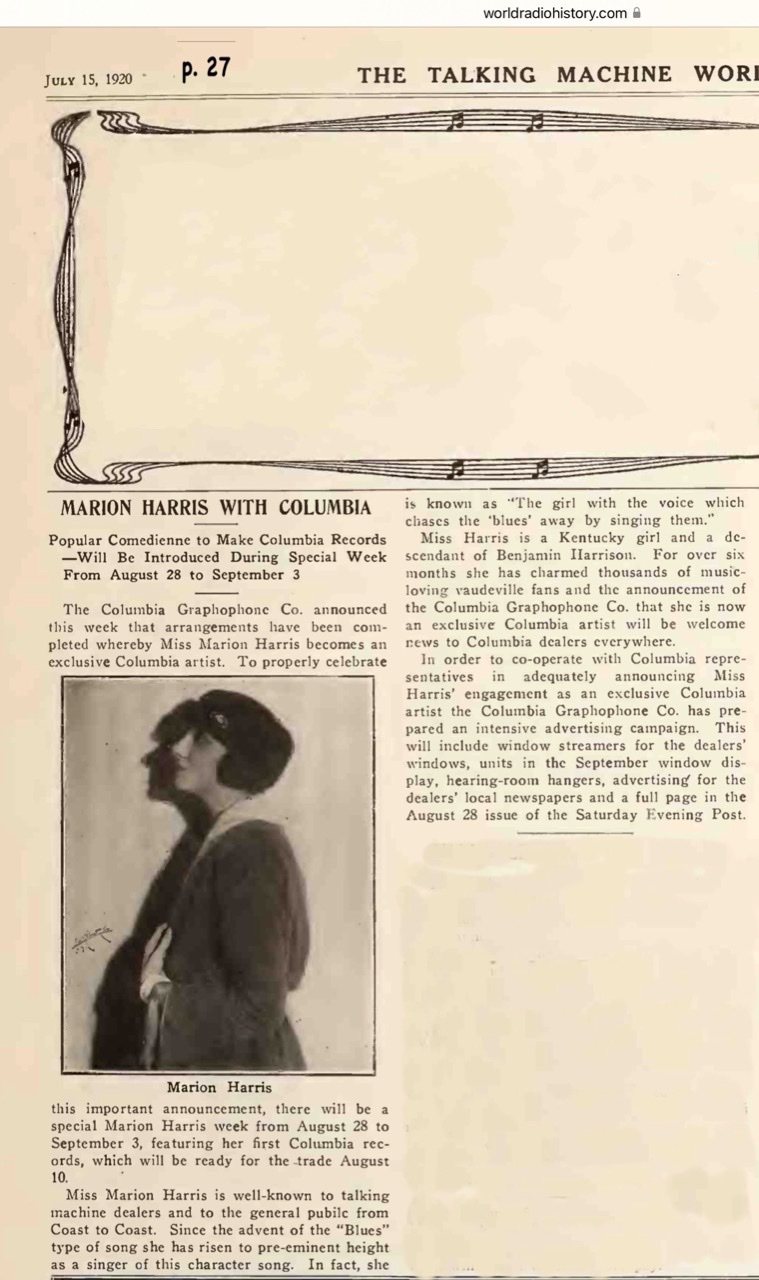

Marion Harris[edit]

|

“Beale Street Blues,” “Who’s Sorry Now,” “The Man I Love” and what many consider the definitive performance of “After You’ve Gone.”

|

Valaida Snow[edit]

|

Ina Ray Hutton[edit]

|

Ina Ray Hutton (1916–1984)

|

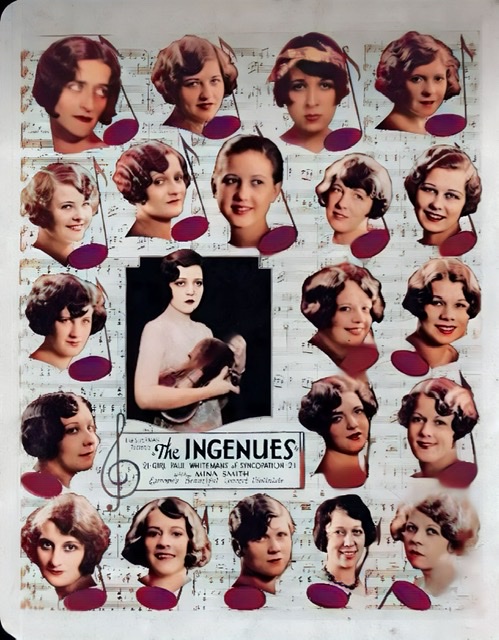

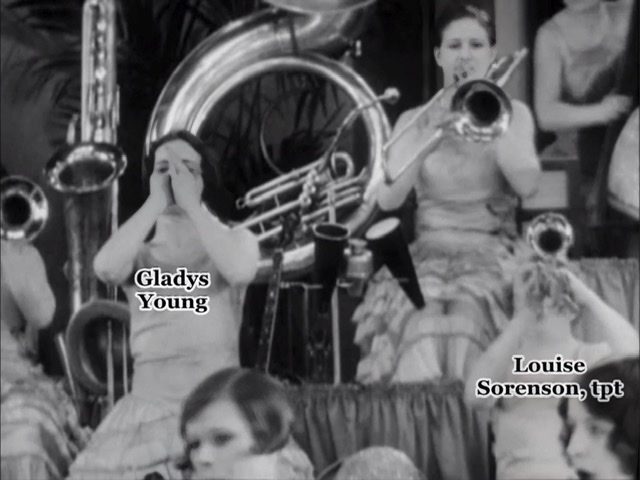

The Ingenues[edit]

(The Ingenues in Sydney, Australia standing in front of Metro Goldwyn Meyer's promotional vehicle for Ben Hur, 'the world's first trackless train", in 1928, photographed by Sam Hood)

(The Ingenues at the Tivoli Theatre, Sydney, Australia 🇦🇺, 1928, taken by photographer Sam Hood) (Photograph in the public domain acknowledged by the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales)

Names of The Ingenues[edit]

“Past members of The Ingenues: Genevieve Brown, Grace Brown, Ruth Carnahan, Babe Colby, Dorothy Donahoe, Juel Donahoe, Mary Donahoe, Pauline Dove, Frances Gorton, Velma Grimm, Billie Jenks, Paula Jones, Marguerite Lichti, Alice Locklin, Margaret Neal, Marie Novak, Blanche Olsen, Alyce Pleis, With Randall, Virginia Roberts, Mina Smith, Louise Sorenson, Lora Standish, Beth Vance, Lucy Westgate, Gladys Young.”[22]

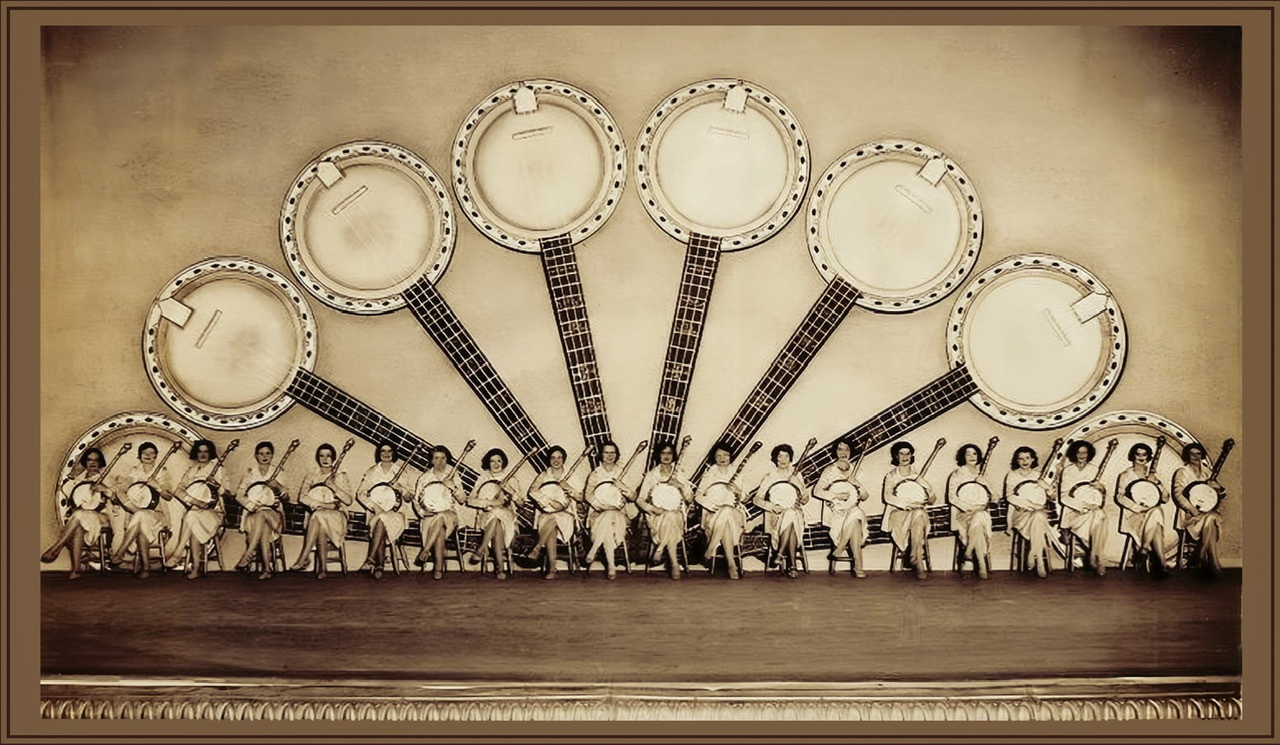

“According to Marie Novak, Florenz Ziegfeld Jr. (1867–1932) attended their show three times that first week and prevailed upon them to appear for four weeks with a further offer of a year's contract in his upcoming Ziegfeld Follies of 1927. Previewing in Boston on August 1, 1927, the 21st Ziegfeld Follies titled "Glorifying the American Girl," had all new songs by Irving Berlin with sets by Joseph Urban, dances by Sammy Lee, costumes by John W. Harkrider, ballets by Albertina Rasch, and the stars Eddie Cantor, Ruth Etting, Cliff Edwards and Claire Luce. The show opened at the New Amsterdam Theatre in New York on August 6, 1927, and The Ingenues were featured in opulent numbers, including Irving Berlin's "Shaking the Blues Away" (later made into a musical comedy film of the same name) with the "Banjo Ingenues" (click to see and hear them perform), and the sensational "Melody Land" first act finale that featured the entire Ingenues Orchestra along with two-piano team Edgar Fairchild (1898–1975) (real name: Milton Susskind) & Ralph Rainger (1901–1942), the Albertina Rasch Girls, and twelve female pianists on all-white baby grand pianos.”[24] (bold not in original)

| ||||

🔸 Metro-Gnomes, a small band fronted by Jack Hylton's then-wife Ennis Parkes.

| 🔸 | 🔸

“Other all-girl bands popular in the 1920s and '30s included Edna White's Trombone Quartet, Bobbie Grice's Fourteen Bricktops, Bobbie Howell's American Syncopators, The Dixie Sweethearts, The Darlings of Rhythm (with tenor saxophone player Margaret Backstrom and alto saxophone player Josephine Boyd), Eddie Durham's All-Star Girl Orchestra, The Parisian Redheads (from Paris, Indiana), and The Twelve Vampires. The best-known and most successful girl band of the '20s was Babe Egan and Her Hollywood Redheads.[25] (bold not in original)

A new crop of all-girl orchestras popped up in the 1930s that included Ina Ray Hutton and Her Melodears, Phil Spitalny's and His Musical Queens, and Dona Drake and Her Orchestra. Conversely, another band was Ramona and Her Men of Music. The new female bands were conventional bands playing popular songs for dancing, with the leader acting as the glamorous and sexy center of attention.

There were dozens of extremely popular, highly visible and audible all-girl jazz bands active during the 1920s and 1930s, including Ina Ray Hutton and HerMelodears, the Harlem Playgirls, Miss Babe Eagan and Her Hollywood Redheads, the Dixie Sweethearts, the Ingenues, Rita Rio and Her All-Girl Orchestra, and Wayman’s Debutantes.

pianists such as Lil Hardin Armstrong

Lovie Austin developed jazz and led their own bands;

in New York, Hallie Anderson, organist

pianist Mattie Gilmore and trombone player and arranger Marie Lucas trained orchestras for theaters.

Sherrie Tucker’s four-year research on New Orleans jazzwomen uncovers a few of the female musicians, mainly pianists and self-trained instrumentalists, who worked in the red light district:

cornet Antonia Gonsalez

Mamie Desdunes, pianist

Dolly Adams, pianist

Camilla Todd, pianist

Edna Mitchell, pianist

Rosalind Johnson, pianist who was also a song writer and received formal musical training.

Jazz women in 1930's America[edit]

excellent all-female group including Jean Starr (1919-1956) on trumpet, Marjorie Hyams on vibes, Marian Gange on guitar, Vicki Zimmer on piano, Cecilia Zirl on bass, and Rose Gottesman on drums.

L'ana (Webster) Hyams[edit]

| L'ana (Webster) Hyams (1912–1997) |

(Main background photo by Ron Reiring taken at Mono Lake August 27, 2014. Purple/pink sky inserted from photo taken by Sue B (firago on Flickr) and shared with the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Science in Action Flickr Group, uploaded on February 18, 2015, with fireworks, musical instruments and PoJ.fm logos added)

Viola Smith[edit]

|

|

propulsive drummer Pauline Braddy (1922–1996) billed as “Queen of the Drums”

Jazz women in 1940's America[edit]

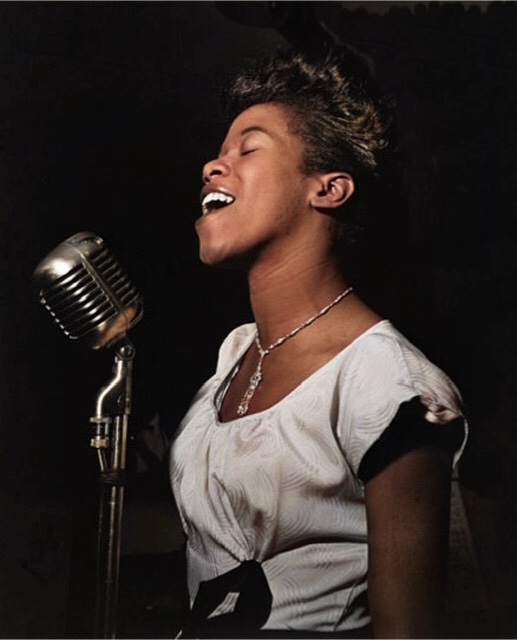

Sarah Vaughn[edit]

Sarah Vaughn (1924–1990)

|

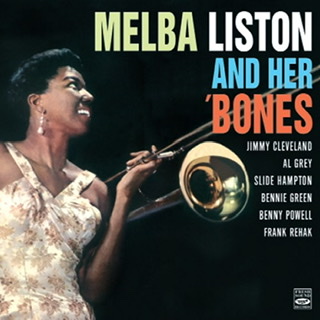

Melba Liston[edit]

|

Melba Liston (1926–1999)

|

Ada Leonard's All-American Girl Orchestra[edit]

|

Ada Leonard's (1915–1997) All-American Girl Orchestra (active 1944→1987)

|

Marjorie Rainey's Rhythmettes[edit]

|

Marjorie Rainey (1915–1997) Rhythmettes |

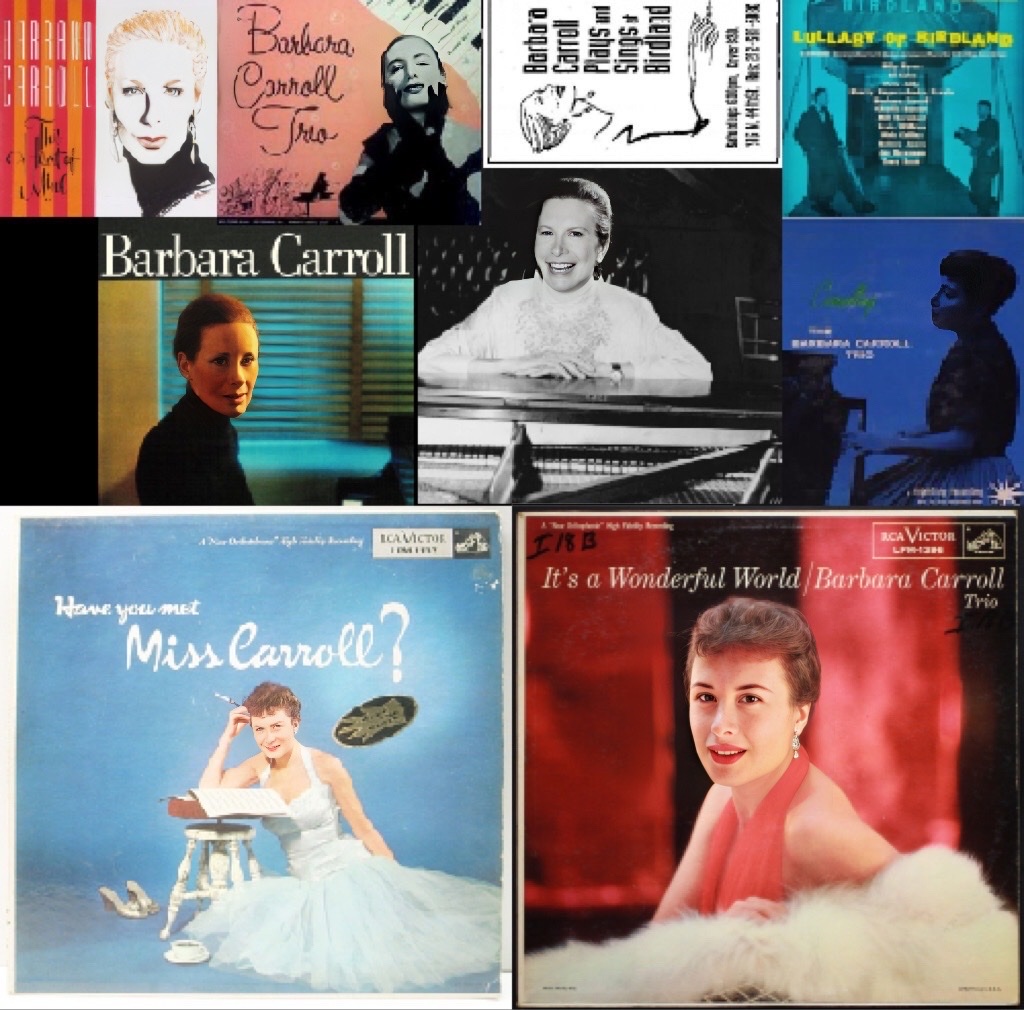

Barbara Carroll[edit]

| Barbara Carroll (1925–2017)

|

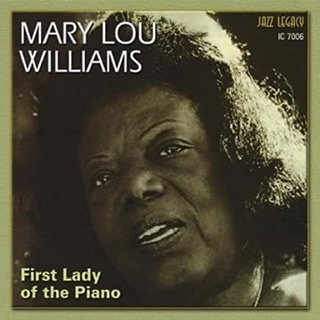

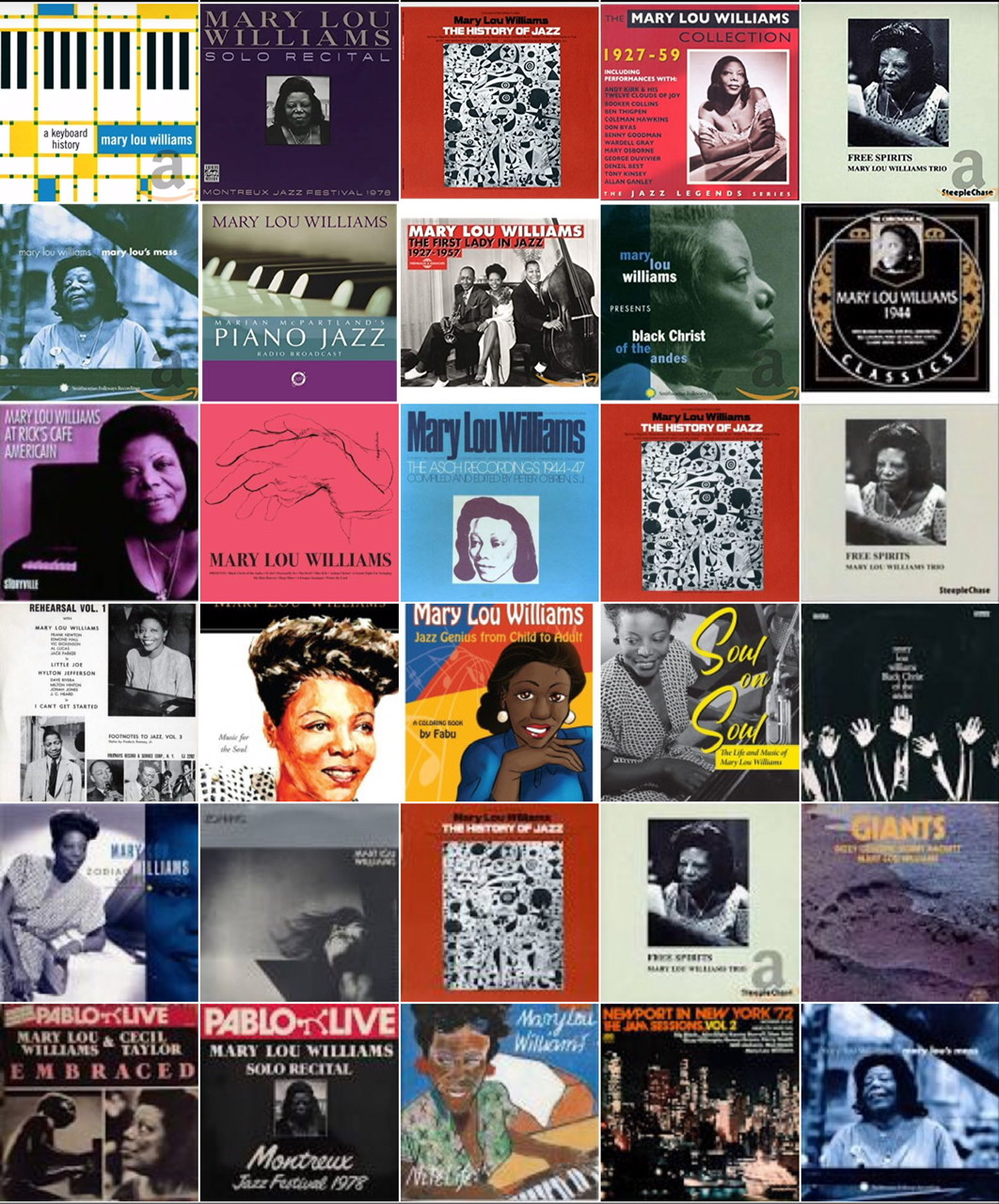

Mary Lou Williams[edit]

(her Harlem apartment, New York, N.Y., ca. August 1947) Mary Lou Williams /

(New York, NY ca. 1946)

(Café Society Downtown, New York, N.Y., ca. June 1947)

(Andy Kirk (1898-1992)) Twelve Clouds of Joy band until April 1930, at which time she became a regular member.

(Photo taken around 1947)

|

Billie Rogers[edit]

|

Billie Rogers (1917–2014)

|

International Sweethearts of Rhythm[edit]

| International Sweethearts of Rhythm

|

Marjorie Hyams[edit]

|

Marjorie Hyams (1920–2012)

|

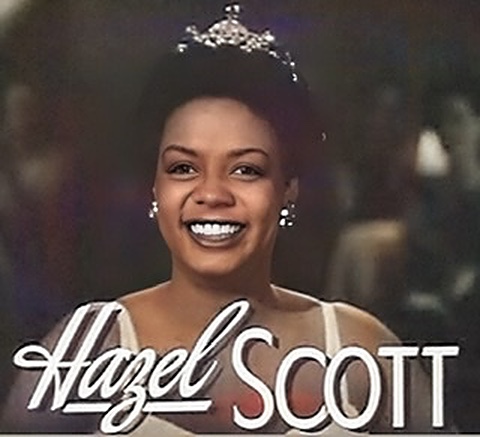

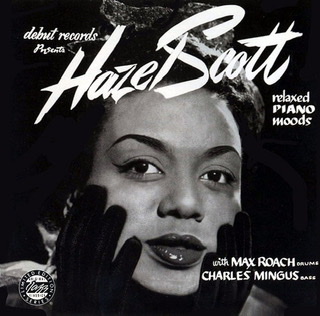

Hazel Scott[edit]

Hazel Scott (1920–1981)  (Click on montage of screen captures to see and hear her swing Chopin for Army–Navy Screen Magazine)

|

Beryl Booker[edit]

Beryl Booker (1922–1978)

|

Dorothy Donegan[edit]

Dorothy Donegan (1922–1998)

|

Jazz women in 1950's America[edit]

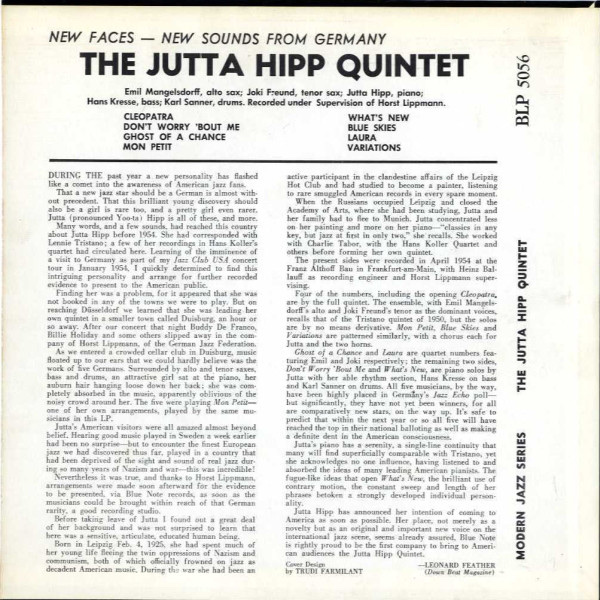

Jutta Hipp[edit]

|

Jutta (pronounced Yoo-ta) Hipp

“As Hipp…matured artistically, she had defined her own artistic standards and revolted when pressured to record music she did not like. She also suffered from severe stage fright throughout her career. Thus being the featured artist at a large performance venue was more of a daunting chore for Hipp than a joyful public celebration of her talent.” – All About Jazz[49] |

Shirley Scott[edit]

|

|

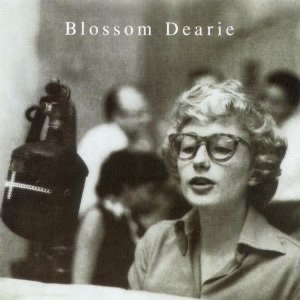

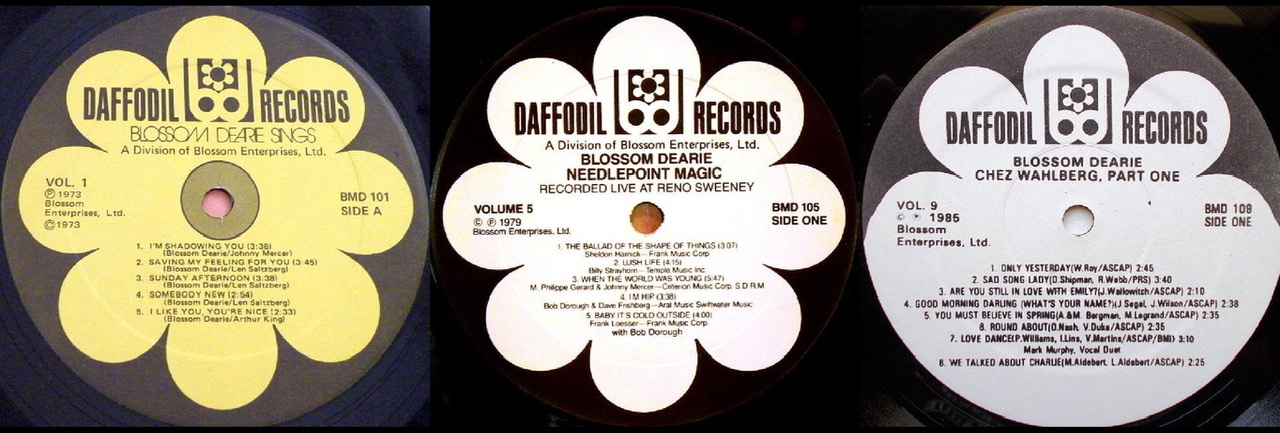

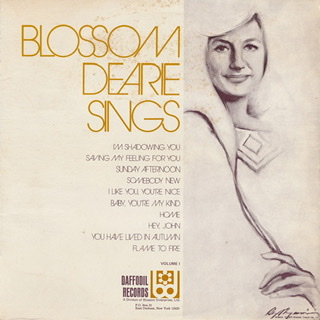

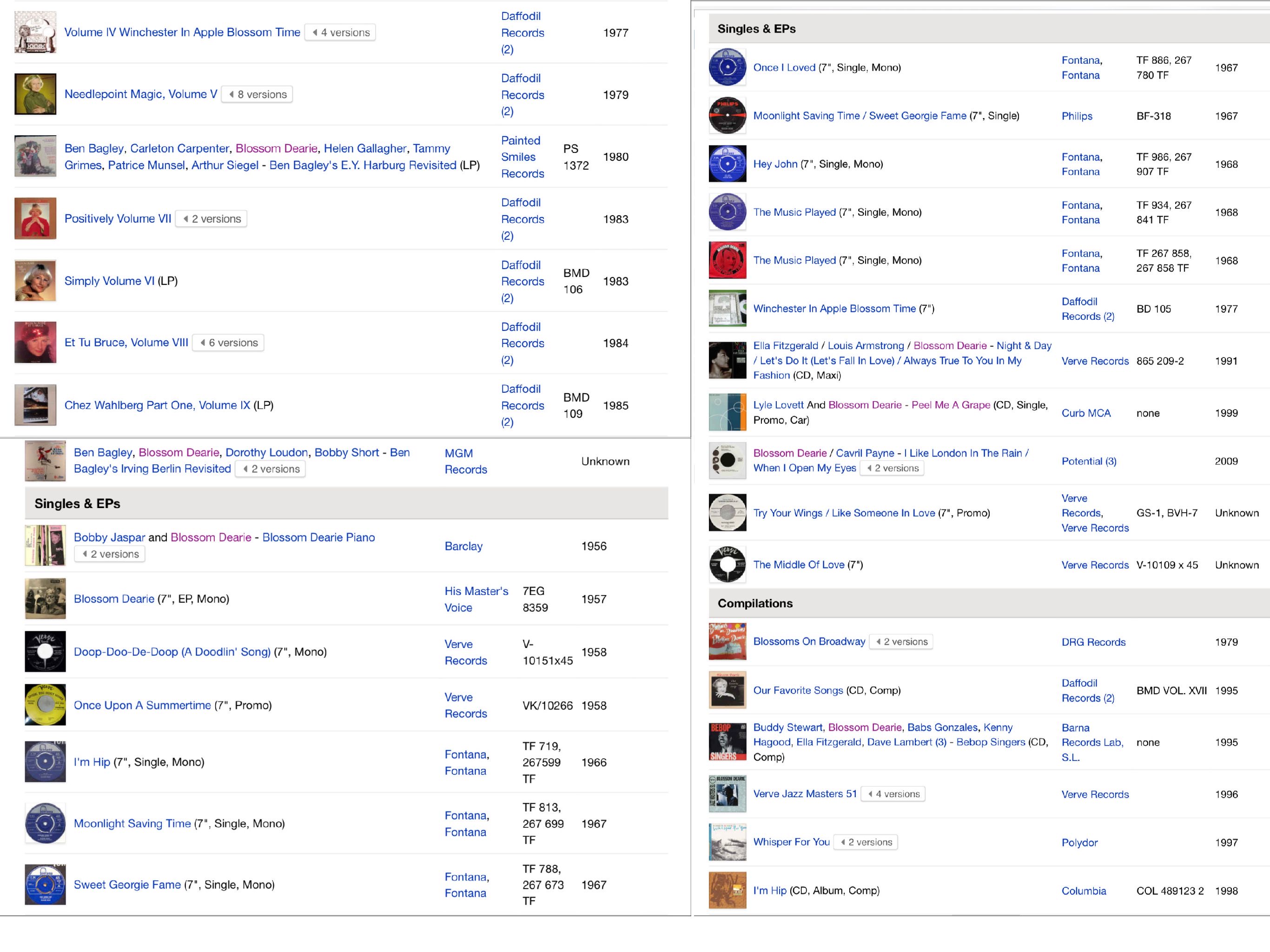

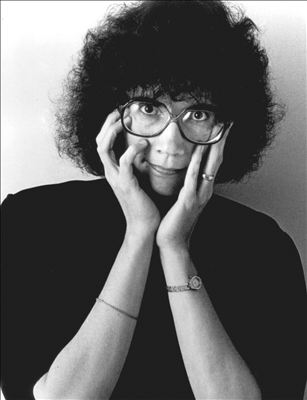

Blossom Dearie[edit]

|

Margrethe Blossom Dearie (1924–2009)

| ||||

Jazz women in 1960's America[edit]

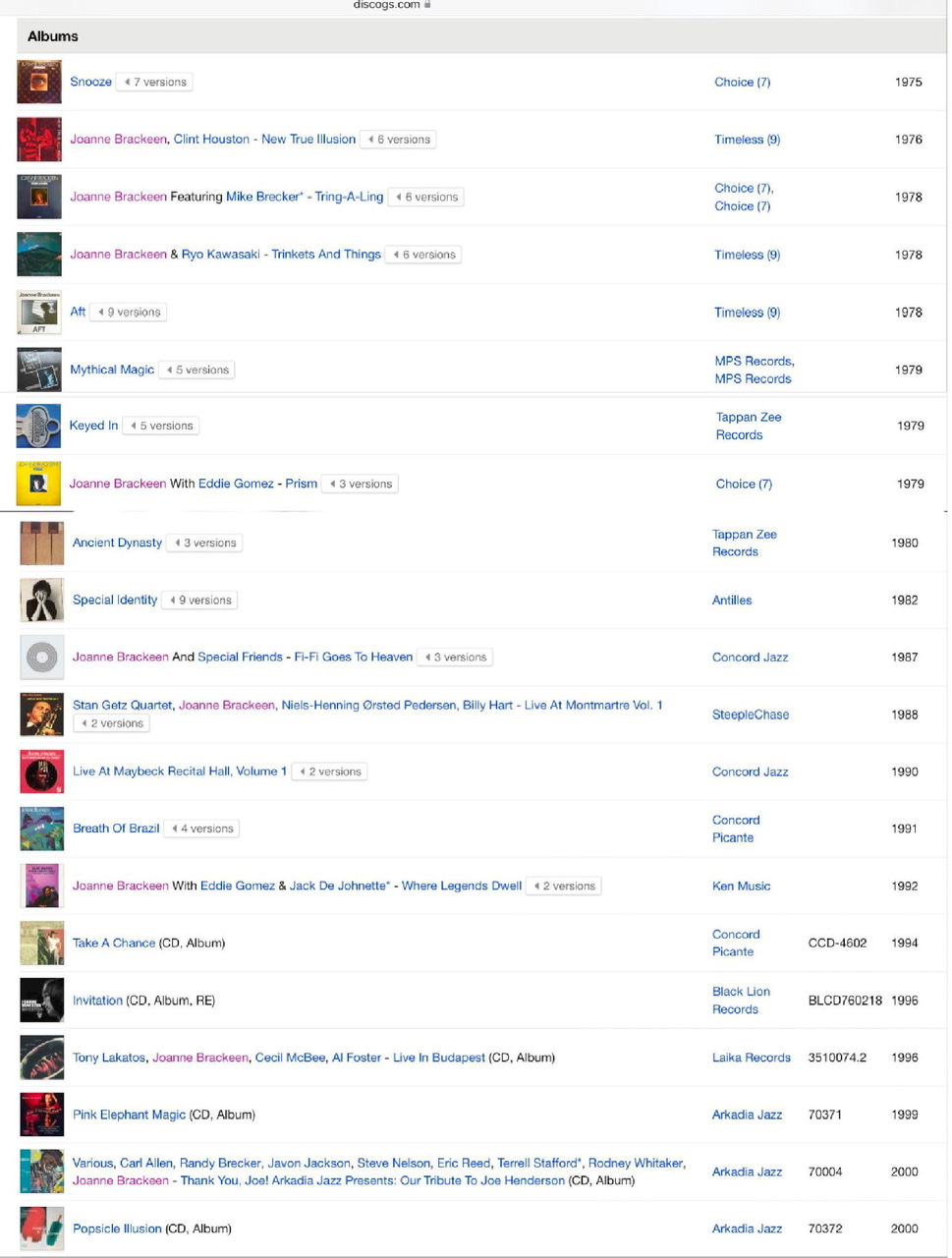

Joanne Brackeen[edit]

|

Selected Discography:

|

Carol Sloan[edit]

Jazz women in 1970's America[edit]

Ahnee Sharon Freeman[edit]

|

Ahnee Sharon Freeman (b. 1958)

|

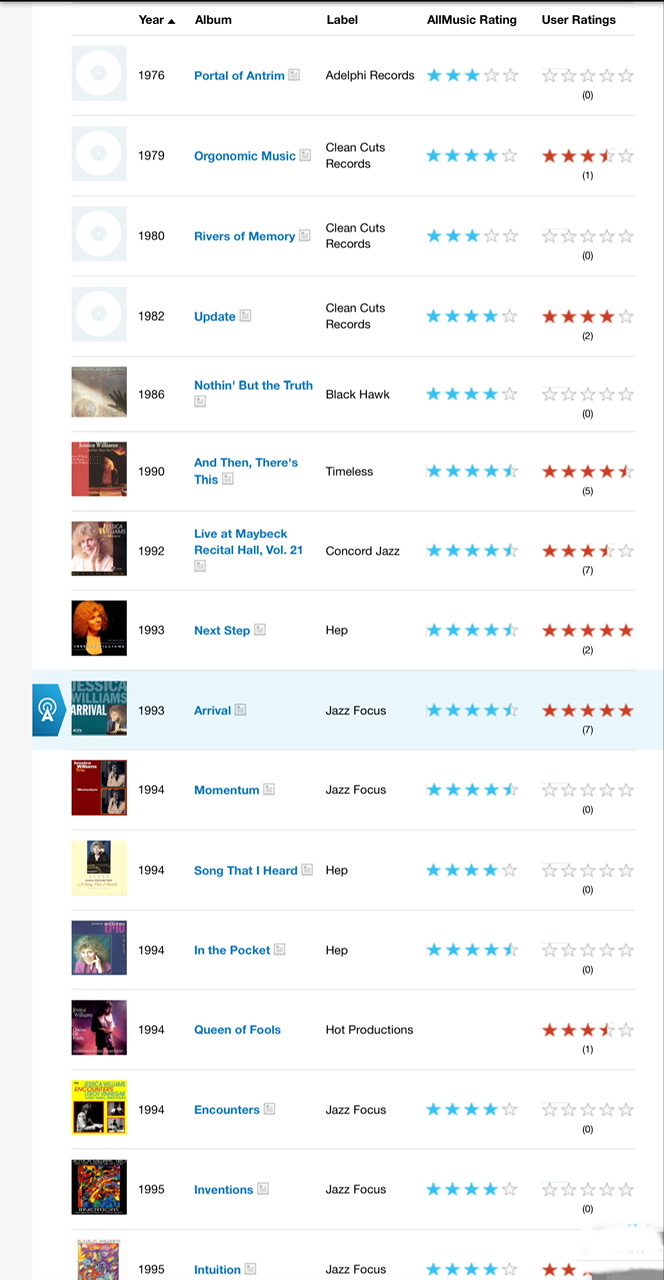

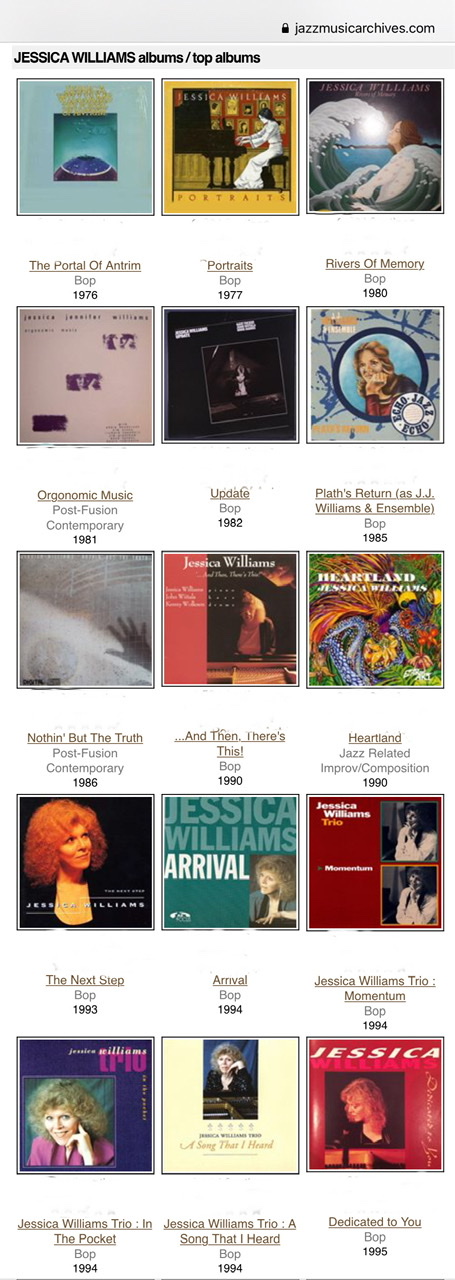

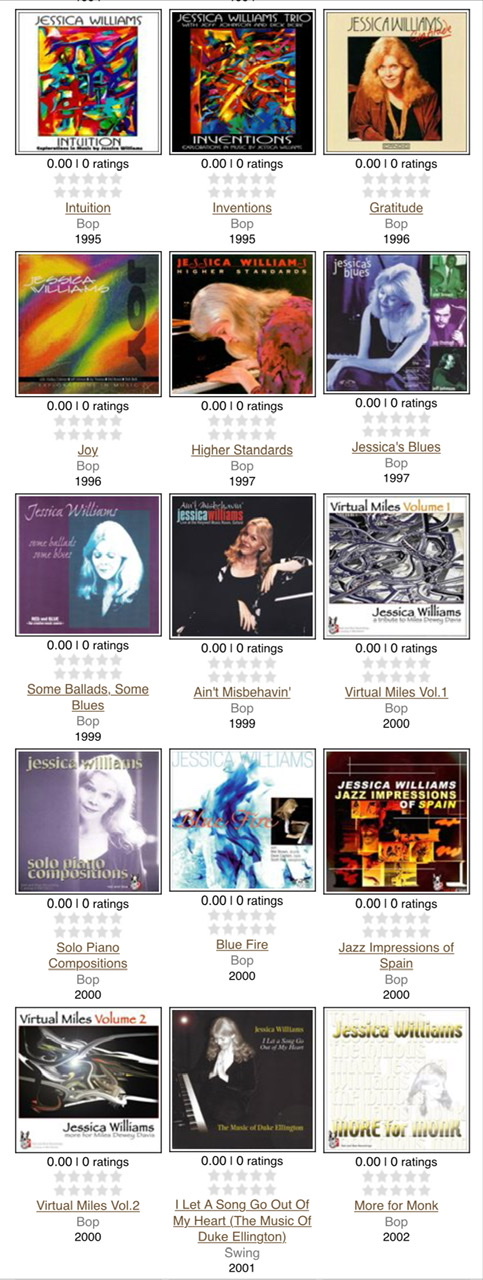

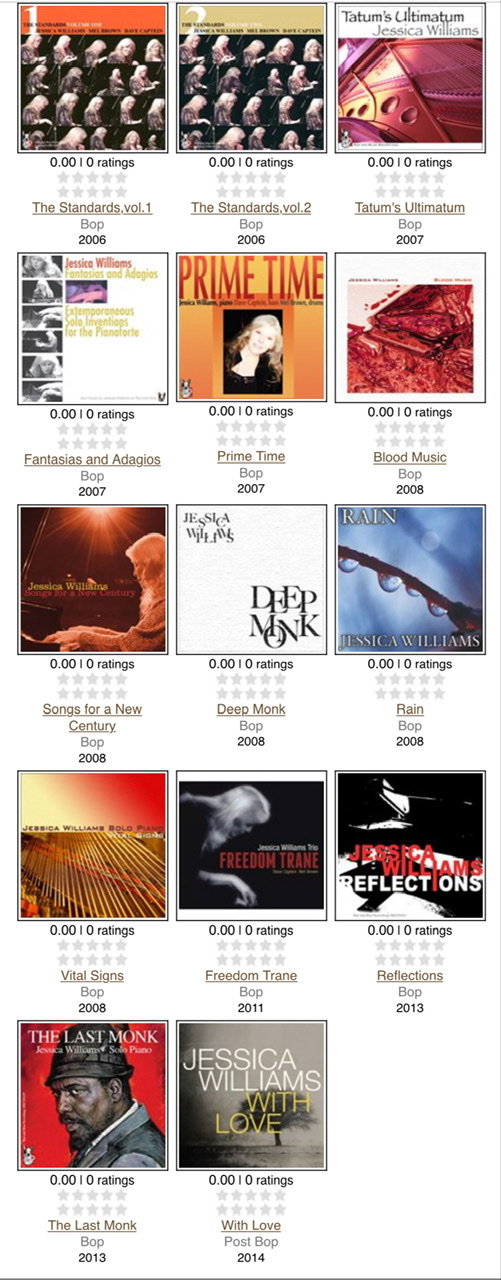

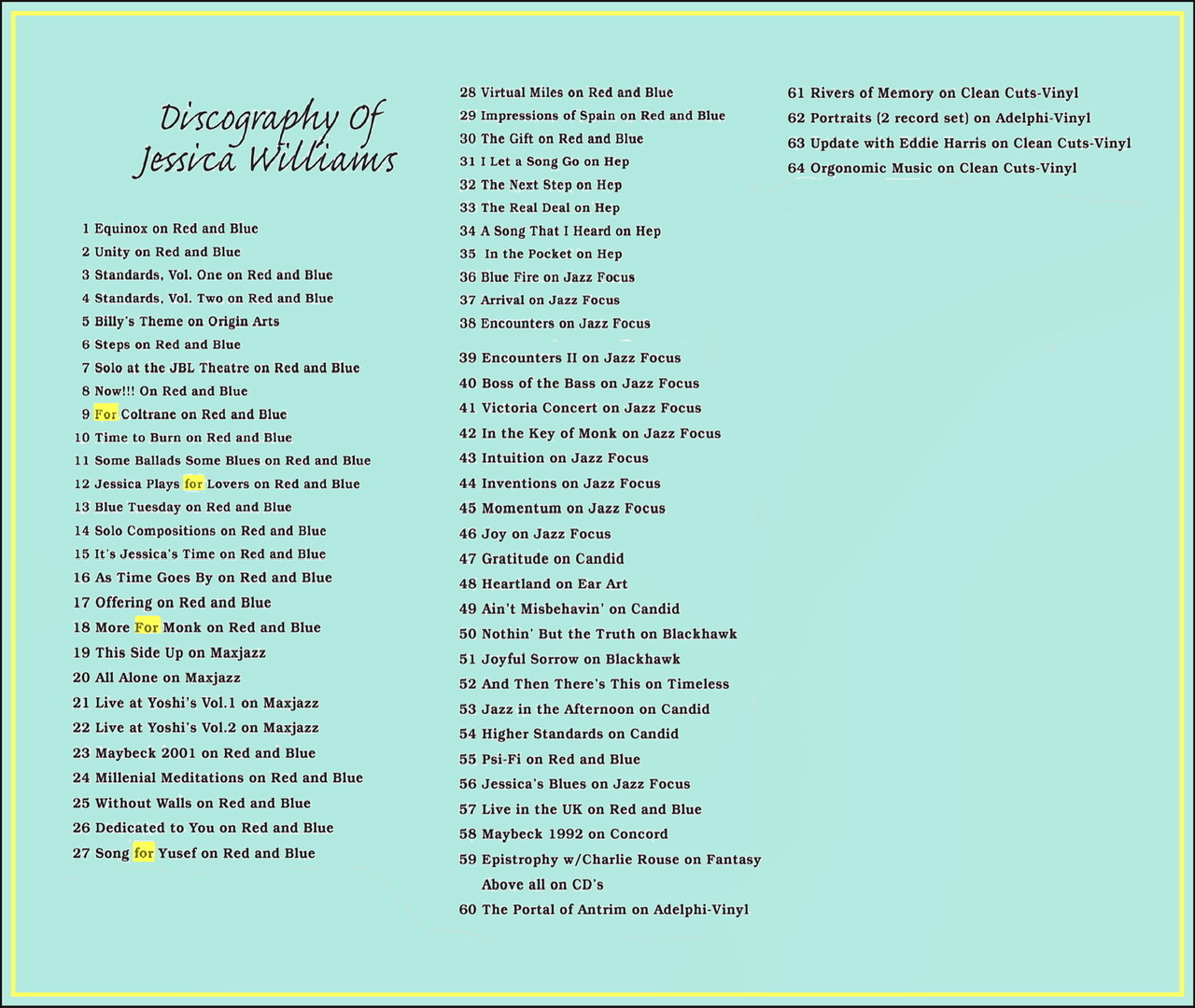

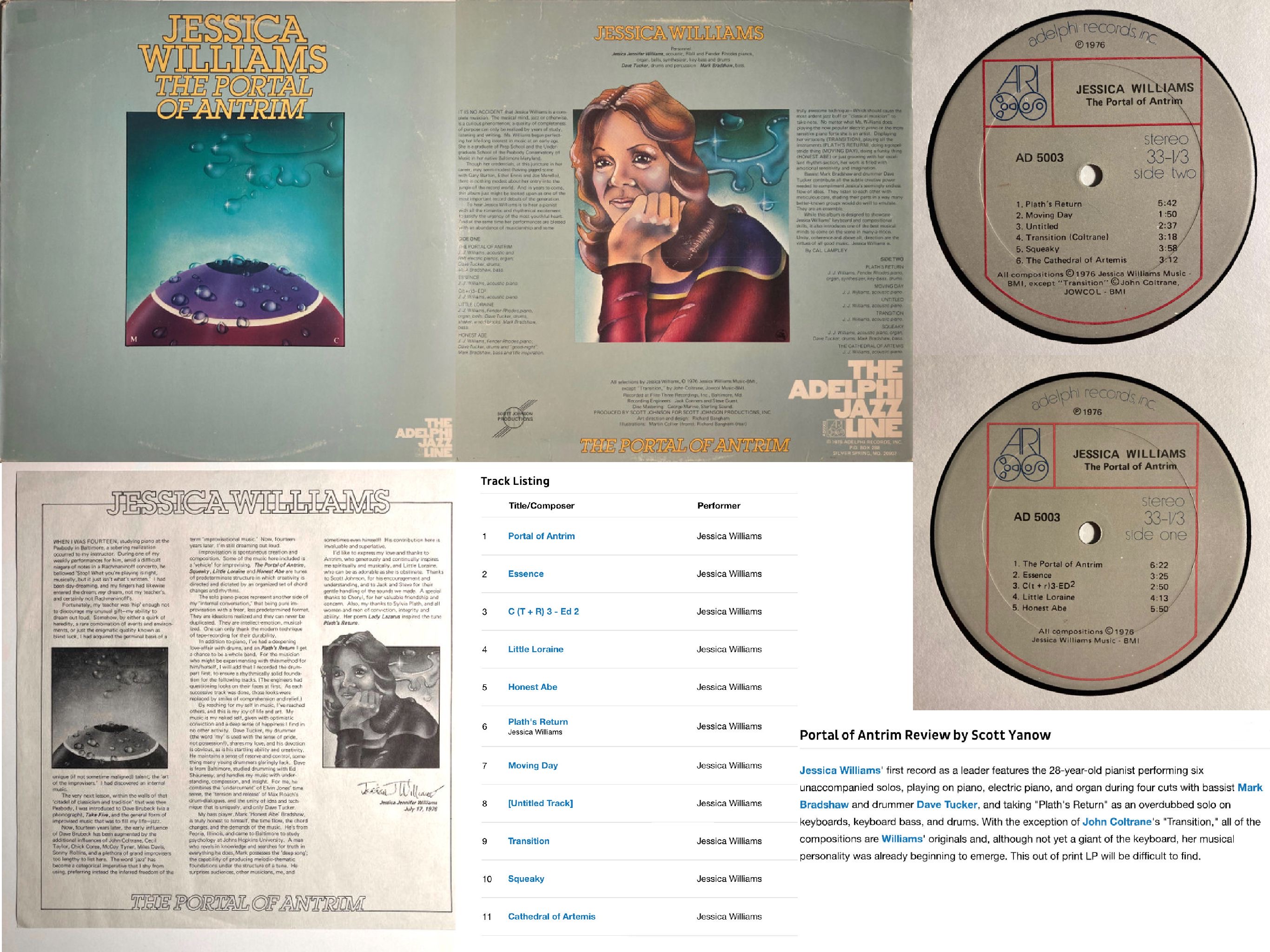

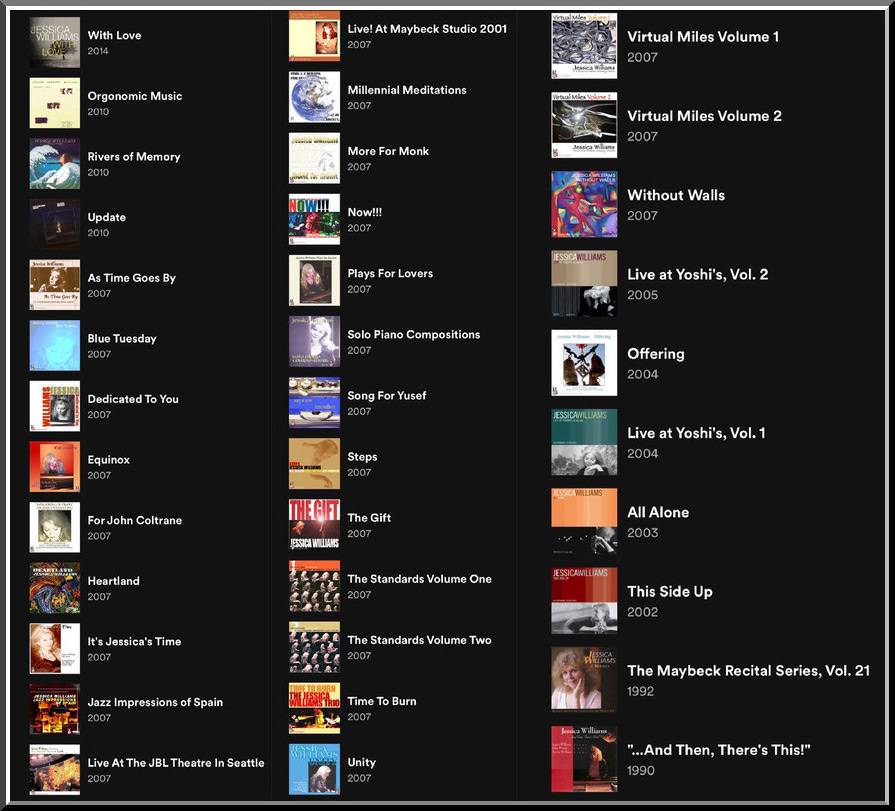

Jessica (Jennifer) Williams[edit]

|

Jessica (Jennifer) Williams (1948–March 12, 2022)

Grammy nominations:

Other Grants and Awards:

|

Jazz women in 1980's America[edit]

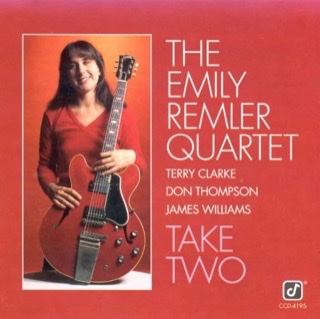

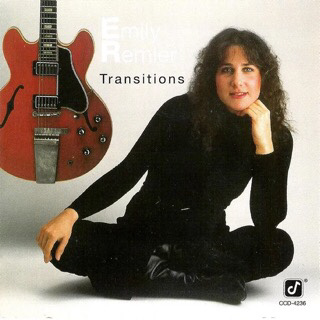

Emily Remler[edit]

|

Emily Remler (1957-1990)

|

Terri Lyne Carrington[edit]

|

Terri Lyne Carrington (b. 1965)

|

Kris Davis[edit]

| 🔸 Kris Davis |

Fay Victor[edit]

| Fay Victor |

Nedra Wheeler[edit]

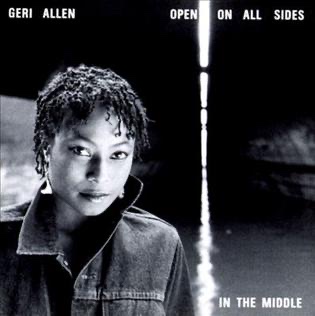

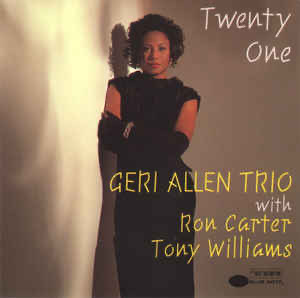

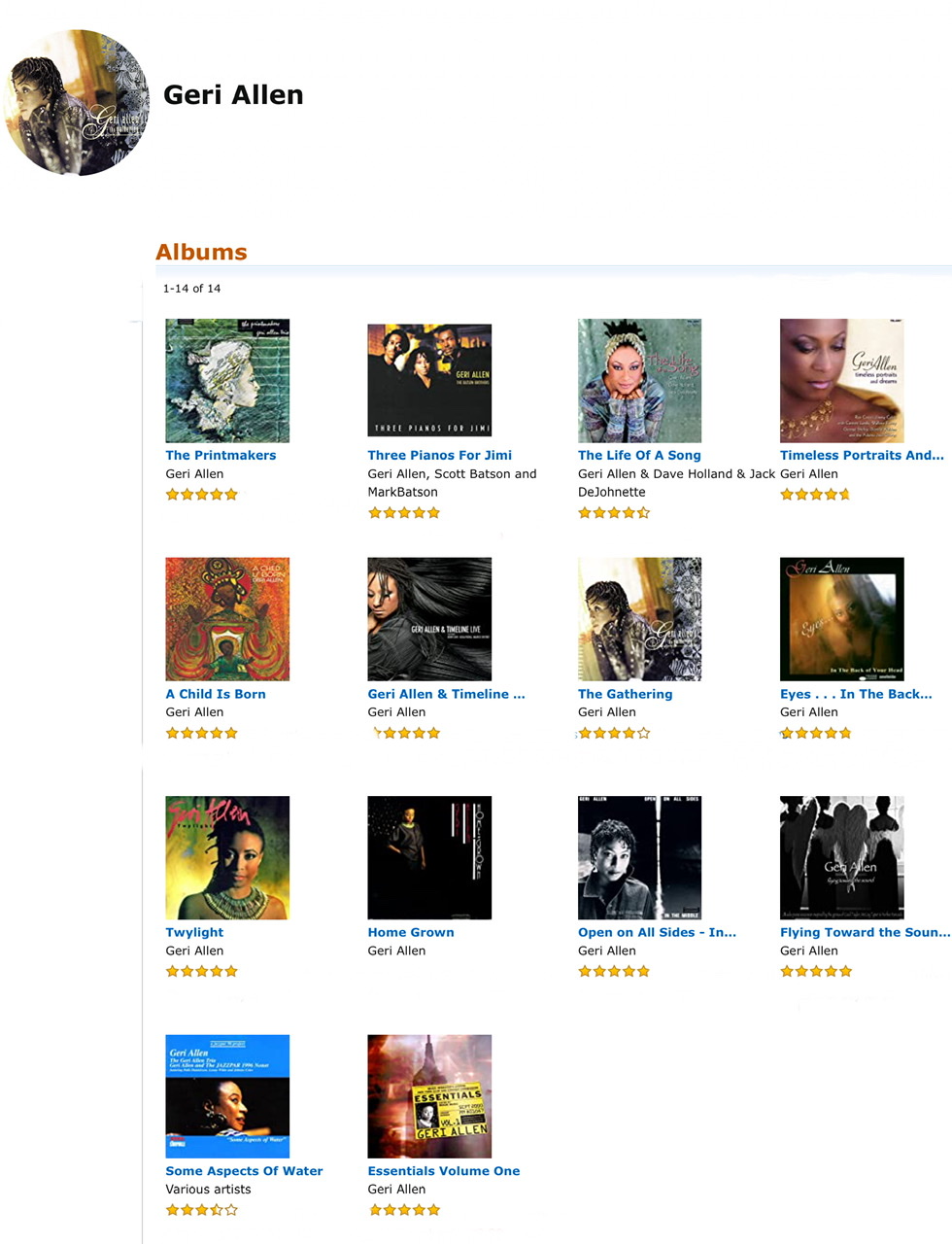

Geri Allen[edit]

|

|

Saskia Laroo[edit]

|

Saskia Laroo (b. 1959)

|

Dena DeRose[edit]

| Dena DeRose (b. 1966)

(Phone snap by Sebastian Scotney) |

Jazz women in 1990's America[edit]

Lena Bloch[edit]

| Lena Bloch (b. 1962)

““In jazz,” muses Lena Bloch, “many things come together that are thought of as opposites: mind and feeling, responsibility and abandonment, looseness and precision, improvisation and composition. I just love that.” (click on the quotation for source)

(Lena Bloch playing her saxophone at Slope Music accompanied by pianist Charles Sibirsky, the owner and founder, in 2018. Click on picture for source.)

(Detail of photograph of Lena Bloch with her band Feathery at The Falcon, Marlboro, New York, March 8, 2020. Click on photograph for source) Selected jazz festivals:

|

Nichole Mitchell[edit]

|

|

Roberta Gambarini[edit]

| Roberta Gambarini (b. 1972)

“If there’s any lingering doubt that Roberta Gambarini has, with remarkable alacrity, joined the upper echelon of jazz singers, "So in Love" should erase it.”[60]

Discography:

As guest vocalist:

|

(The International Space Station and Soyuz TMA-07M spacecraft were making their relative approaches on December 21 (year unknown).

Original photograph from NASA. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel with PoJ.fm logos added in between.

DIVA jazz orchestra[edit]

| DIVA Jazz Orchestra

Melissa Slocum (born July 26, 1961) is an American double bass player who is active in both jazz and classical music. The following is an English translation of the German Wikipedia page on Melissa Slocum. “Life and work: Slocum grew up in a musician household in Ohio (her father was a horn player in the Cleveland Orchestra; her mother, a professor of medieval studies, played the viola) and began playing the piano at the age of three. She was encouraged by her parents to study classical music. She started playing bass guitar at the age of twelve, and a year later she began performing professionally as a musician. A gifted student, she graduated from high school at the age of fifteen. By age eighteen, she had earned a bachelor's degree in classical piano music from Youngstown State University; she spent another year there to get a second degree in art history, specializing in ancient Egyptian art.

“When Dianne called Marian (McPartland), the quintet was preparing for a three-night gig in Rochester, New York, and a live recording. Marian had picked an eclectic bouquet of players. Veteran guitarist Mary Osborne, whom many called the best guitarist of her generation, was already well known to New York audiences. Dottie Dodgion on drums had made her reputation playing and singing in Chicago, Washington, D.C., and San Francisco with Charles Mingus and Al Cohn, among others. Vi Redd's soulfully fearless alto saxophone sound had complimented the groups of both Max Roach and Dizzy Gillespie. Marian picked bassist Lynn Milano, the youngest of the group by a generation and a graduate of Eastman, because her sound contradicted her petite size. None of the women had played together as a group before.[61] (bold not in original) “ . . . Goodman, girls learned to swing as strongly as their dance partners. But firmly established cultural stereotypes kept denying that this was so. In a February 1938 Down Beat opinion piece, an anonymous writer stated, "Women as a whole are emotionally unstable, which prevents their being consistent performers on musical instruments." Bandleader and saxophonist Peggy Gilbert lost no time writing a rebuttal. "The manager is constantly reminding the girls not to take the music so seriously, but to relax, to smile," Gilbert wrote in Down Beat in April of 1938. "How can you smile with a horn in your mouth? How can you relax when a girdle is throttling you and the left brassiere strap holds your arm in a vice?" The undeniable truth was that a female jazz artist's popularity was based on visual attributes rather than musical expertise. Long, flowing, tight-waisted gowns, with billowing sleeves, in cotton candy colors, defined the dress code. Saxophonist Roz Cron remembers a particularly humiliating outfit. "I was playing at the Oriental Theater in Chicago with Ada Leonard's band," Cron recalls. "The manager brought out this god-awful, pink thing and said that was what I was to wear. It had all these flounces and flares and ruffles. I was mortified. I'm a professional, not a dress up doll. I hated that costume with a passion." Another member of the band stated, "A man could have white hair and glasses and weigh 300 pounds, but if he could play, great. The girls had to look like starlets. And the things they put on us were unbelievable."[63] (bold not in original) “Even the highly successful and popular all-female group Hour of Charm, led by Phil Spitalny, one of the few men to front a girl band, was founded in musical compromise. Spitalny publicly made it clear that he wasn't looking for a powerful, hard-swinging sound. In a band that employed more violins than brass, two pianos, and a harp, it's not surprising their repertoire consisted of mostly mellow, sweet tunes. That also pleased the sponsors of the Sunday night radio show of the same name. The listening public deemed Hour of Charm the ideal all-female band. It wasn't only the jazz world that discriminated against female players. Girl harpists and violinists might be acceptable on a stage clouded with taffeta and sequined dresses. Anonymous female trombonists and bassists could be heard on radio broadcasts without public outcry. But in the male dominated world of symphony orchestras, the subject of female members wasn't even open for discussion. It would be 1982 before the Berlin Philharmonic hired a woman. In Vienna it was 1997. [65] (bold not in original) |

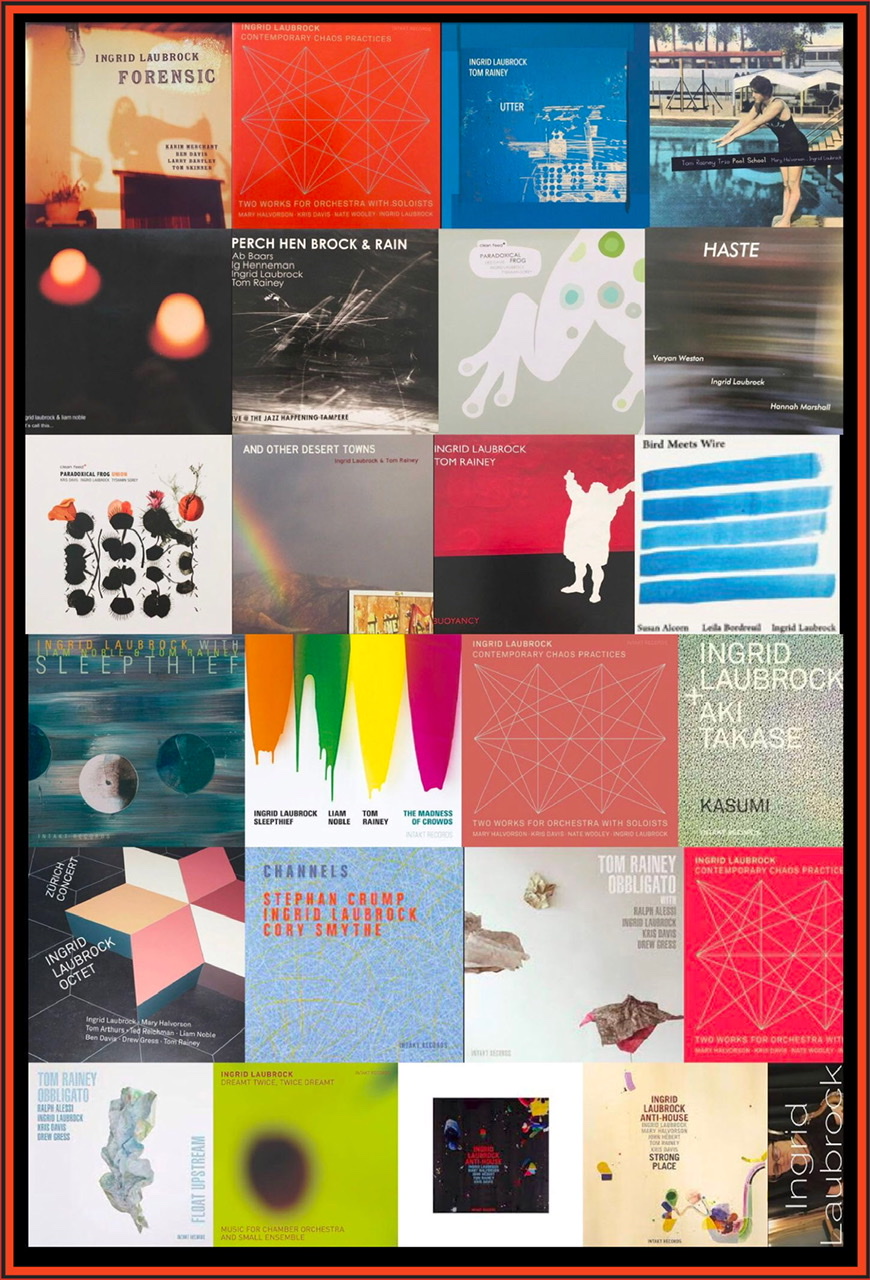

Ingrid Laubrock[edit]

| Ingrid Laubrock (b. 1970)

(Craig Taborn on piano, Miya Masaoka on koto, Sam Pluta on electronics, Peter Evans on trumpet and piccolo trumpet,

|

Jazz women in the 20th century[edit]

🔸 Ingrid Jensen (b. 1966) Canadian jazz trumpeter.

🔸 Matana Roberts (b. 1975) American sound experimentalist, visual artist, jazz saxophonist and clarinetist, composer and improviser based in New York City and has been an active member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM).

🔸 Barbara Thompson (1945–2022) British alto and baritone saxophonist, flutist, pianist, clarinetist and composer who played in many jazz genres, including Latin jazz and big band.

🔸 Maria Schneider (b. 1960) American composer, jazz orchestra leader, and multiple Grammy Award winner.

🔸 Geri Allen (1957–2017) American (Pittsburgh) pianist, composer, and educator.

🔸 Renee Rosnes (b. 1962) Canadian jazz pianist, composer, and arranger.

🔸 Cindy Blackman Santana (b. 1959) American jazz and rock drummer.

🔸 Jane Bunnett (b. 1956) Canadian soprano saxophonist, flautist, bandleader, and educator especially known for performing Afro-Cuban jazz and often traveling to Cuba.

🔸 Mary Lou Williams (1910–1981). American pianist, composer, arranger, and mentor who could play all jazz styles from Ragtime to free jazz.

🔸 Dorothy Donegan (1922–1998) American jazz pianist, vibraphonist, and vocalist, primarily known for performing in the stride piano and boogie-woogie style as well as playing bebop, swing jazz, and even classical music.

🔸 Marian McPartland (1918– 2013) English-American jazz pianist, composer, and writer. hosted "Marian McPartland's Piano Jazz" on National Public Radio from 1978 to 2011.

🔸 Mary Osborne (1921–1992) American jazz guitarist.

🔸 Toshiko Akiyoshi (b. 1929) Japanese-American jazz pianist, composer, arranger, and bandleader.

🔸 Carline Ray (1925–2013) American jazz pianist, guitarist, and vocalist. She was a member of the International Sweethearts of Rhythm.

🔸 Janice Elaine Robinson (b. 1951) American (Pennsylvania) trombonist.

🔸 Patti Bown (1931–2008) American jazz pianist, composer, and singer.

🔸 Andrea Brachfeld (b. 1955) American jazz and Latin jazz flutist.

🔸 JoAnne Brackeen (b. 1938) American jazz pianist and music educator.

🔸 Valerie Capers (b. 1935) American pianist, composer, and music educator.

🔸 Sue Evans (b. 1951) American jazz, pop, classical, and studio percussionist/drummer.

🔸 Corky Hale (b. 1936), American jazz harpist, pianist, flutist, and vocalist. She has been a theater producer, political activist, restaurateur, and the owner of the Corky Hale women's clothing store in Los Angeles, California.

🔸 Emmelyne "Emme" Kemp (b. 1936), pianist, vocalist, band leader, Broadway composer, actress, lecturer, and an American music researcher. A protégé of Eubie Blake and best known as a Broadway composer and actor for Bubbling Brown Sugar. Acted in the Woody Allen film "Sweet and Lowdown." She has performed throughout the United States, Germany and Japan.

🔸 Jill McManus (b. 1940), American jazz pianist, composer, teacher, and author.

🔸 Nina Sheldon (b. 1940), American pianist, singer, composer and lyricist.  Led the house band at the Village Gate (1974 –1977) in New York City. Has played with Sonny Stitt, George Coleman, Maxine Sullivan, Budd Johnson, Bobby Hackett, and Vic Dickenson. Taught jazz history and improvisation at the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore, Maryland. Performed at major jazz festivals such as Newport jazz festival and the Kool jazz festival in New York and the Kansas City Women's jazz festival.

Led the house band at the Village Gate (1974 –1977) in New York City. Has played with Sonny Stitt, George Coleman, Maxine Sullivan, Budd Johnson, Bobby Hackett, and Vic Dickenson. Taught jazz history and improvisation at the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore, Maryland. Performed at major jazz festivals such as Newport jazz festival and the Kool jazz festival in New York and the Kansas City Women's jazz festival.

🔸A set of three records providing background on the involvement of women with jazz, produced by Bernard Brightman. “Women in Jazz,” collections of recordings made between 1926 and 1961, providing a very convincing demonstration that women, singly and in groups, have been making impressive contributions to jazz since its earliest recorded days and doing it for the most part, in relative anonymity.

🔸 Listen to "Women in Jazz: Piano players."

🔸 Margie Hyams (1920–2012), played vibes in Woody Herman's band in the 40's and in George Shearing's original quartet.

🔸 Vi Burnside (1915–1964), American saxophonist.

🔸 Vi Redd (b. 1928), American saxophonist.

🔸 Valaida Snow (1904–1956), American trumpeter.

🔸 Jean Starr (Jones) (circa 1900– ?), American trumpeter. Daughter of Daniel Williams. She is recorded on the album "Jazz Women: A Feminist Retrospective" on the song "Moonlight On Turham Bay" with L'Ana Hyams and other female performers. She was also recorded as part of the International Sweethearts of Rhythm, a group she joined in 1940, including on the song "Tuxedo Junction." She also performed with the Jimmie Lunceford Band and played with the Benny Carter Orchestra. In her later years, she was part of Eddie Durham's All-Star Girl Orchestra. She led the Bronzeville socialite group the Royalites.

🔸 Marion Gange (1912–2012), an American guitarist.

🔸 Terry Pollard (1931–2009), American vibist and pianist.

🔸 Lovie Austin (1887–1972), an American pianist in Chicago in the '20s around whom a whole school of male musicians flourished.

🔸 International Sweethearts of Rhythm (1937–1949), an all‐woman big band.

🔸 Una Mae Carlisle (1915–1956), an American singer and pianist who recorded with Fats Waller and whose accompanying group follows the patterns of Waller's sextet.

🔸 Beryl Booker (1922–1978), an American pianist who is heard urging Miles Davis’s trumpet along on Tadd Dameron's (1917–1965) “Squirrel."

🔸 Kathy Stobart (1925–2014), an English mostly tenor saxophonist.

🔸 Jutta Hipp (1925–2003), a German pianist.

Jazz women in 21st Century[edit]

Ingrid Jensen, Anat Cohen, Sherrie Maricle and the indomitable DIVA Jazz Orchestra, Geri Allen, Cindy Blackman, Tia Fuller, Lakecia Benjamin

| Kris Davis (b. 1980)

|

Esperanza Spalding[edit]

| Esperanza Spalding (b. 1984)

|

Nubya Garcia[edit]

|

|

Sarah Milligan[edit]

| Sarah Milligan (b. 1998)  Sarah Milligan (b. 1998), saxophonist

|

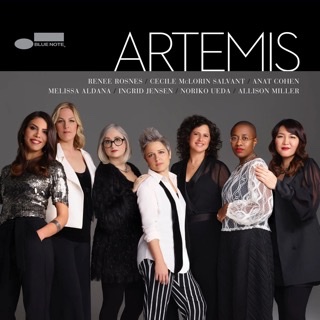

ARTEMIS[edit]

|

ARTEMIS  (from l. to r.: bassist Noriko Ueda, tenor saxophonist Melissa Aldana, clarinetist Anat Cohen, pianist Renee Rosnes, drummer Allison Miller, trumpeter Ingrid Jensen, and vocalist Cécile McLorin Salvant)

🔸 releases their first album |

Musician's Biography Websites[edit]

![]() See Wikipedia: American women jazz musicians

See Wikipedia: American women jazz musicians

![]() See Wikipedia: American women jazz singers

See Wikipedia: American women jazz singers

![]() See Wikipedia: Women jazz musicians

See Wikipedia: Women jazz musicians

![]() See Wikipedia: Women jazz singers

See Wikipedia: Women jazz singers

Rossano Sportiello

Catherine Russell

Niki Haris

Cécile McLorin Salvant

Veronica Swift jazz vocalist and composer

Tomeka Reid cellist

Yazz Ahmed flugelhornist and composer from Bahrain 🇧🇭 and London 🏴.

Ariadna Castellanos (Spain) pianist

| Check out their websites Click on picture or lighter blue hyperlinks for more information | ||

|---|---|---|

| Picture |

Name |

Roles |

|

Helen Sung |

American 🇺🇸 jazz pianist and composer |

|

Lorraine Geller |

American 🇺🇸 Bop pianist |

|

Geri Allen |

|

|

Elaine Elias |

Brazilian 🇧🇷 jazz pianist, singer, composer, arranger and producer |

|

Connie Han |

American 🇺🇸 jazz pianist, Steinway Artist, and Mack Avenue Records recording artist |

|

Renee Rosnes |

Canadian 🇨🇦 jazz pianist, composer and arranger |

|

Connie Crothers |

American 🇺🇸 avant-garde & free jazz pianist, educator and composer |

|

Judy Carmichael |

American 🇺🇸 Ragtime, jazz, stride, and swing pianist and singer |

(Photograph by Lauren Lancaster in The New Yorker 2018) |

Carla Bley |

American 🇺🇸 jazz composer, arranger, bandleader, and keyboardist |

|

Joanne Brackeen |

American 🇺🇸 jazz pianist, soloist, bandleader, and music educator |

(Colorized Photo source from JM L) |

Alice Coltrane |

|

|

Champian Fulton |

American 🇺🇸 jazz singer and pianist |

|

Carmen Staaf |

American 🇺🇸 pianist, accordionist, educator (taught at Berklee College of Music 2005–2009), and winner of the Mary Lou Williams Piano Competition (2009). |

|

Sue Richardson |

English 🇬🇧 singer, trumpet player, and composer “She plays swinging jazz trumpet, with excellent technique and a remarkable command of a variety of styles. She sings with a musician's phrasing and her songs come with proper tunes and grown-up harmonies attached—a rarity in itself.” — The Guardian

|

|

Sheryl Bailey |

American 🇺🇸 jazz/Bebop guitarist and music educator at Berklee College of Music

|

| Chilean 🇨🇱 tenor saxophonist and studio teacher at New England Conservatory’s Jazz Studies Department

| ||

|

American 🇺🇸 jazz drummer and educator | |

|

|

New Zealand 🇳🇿 (lived in Australia 🇦🇺 since 1960) pianist, composer, soloist, bandleader, arranger, and educator at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music

|

|

Japanese pianist  An innovative bandleader and soloist, as well as a prolific recording artist in ensembles ranging from duos to big bands on over 100 CDs as leader or co-leader.

| |

|

Lily Carassik |

English 🏴 trumpeter and composer

|

|

American jazz guitarist | |

(Detail of photo by Bill Shakespeare)

|

Trish Clowes |

British saxophonist, composer, educator, and musician on tenor and soprano saxophone. Clowes has played music in these genres: avant-garde, post-bop, & modern jazz, classical, and classical crossover.

|

Internet & Bibliographic Resources on Women in Jazz[edit]

NOTE: The information below varies in formatting and does not usually conform to standard bibliographic formatting for ease of reading.

Eight Rising Women Instrumentalists from 2016[edit]

![]() Rusty Aceves, "Eight Rising Women Instrumentalists," "On the Corner," SFJazz.org, June 1, 2017, (originally posted March 1, 2016). Accessed July 30, 2022.

The eight instrumentalists include:

Rusty Aceves, "Eight Rising Women Instrumentalists," "On the Corner," SFJazz.org, June 1, 2017, (originally posted March 1, 2016). Accessed July 30, 2022.

The eight instrumentalists include:

- Bria Skonberg (b. 1984) — Award-winning Canadian jazz trumpeter and vocalist, winner of the New York Bistro Award for Outstanding Jazz Artist (2014) as well as a Swing! Award given by Jazz at Lincoln Center (2015). In 2013 she earned a Jazz Journalists' Association nomination for “Up and Coming Jazz Artist of The Year” and has been included in DownBeat Magazine’s Rising Star Critics‘ Poll 2013 & 2014. Skonberg swept the 2014 Hot House Jazz Magazine Awards in all categories nominated: Best Jazz Artist, Best Trumpet, Best Female Vocalist and Best Group for the Bria Skonberg Quartet. As a bandleader and guest artist, she has performed at over fifty jazz festivals in North America, Europe, China and Japan and in New York City since 2010 has headlined at Symphony Space, Birdland, The Iridium, Dizzy's Cafe, and Cafe Carlyle.

(Photo in upper left by Thomas Concordia)

- Melissa Aldana (b. 1988) — Chilean tenor saxophonist and winner of the 2013 Thelonious Monk International Saxophone Competition and Berklee College of Music Presidential scholar graduate who studied with alto saxophonist Greg Osby (b. 1960) and tenor saxophonist Joe Lovano (b. 1952).

(Most photos taken in 2015)

Listen to an interview of Melissa Aldana in 2022.

- Natalie Cressman (b. 1992) — American jazz trombonist and vocalist who has worked with Phish leader Trey Anastasio (b. 1964) as well as with Nicholas Payton (b. 1973), Wycliffe Gordon (b. 1967), Pete Escovedo’s (b. 1935) Latin Jazz Orchestra, American 🇺🇸 musician and world music giant Jai Uttal (b. 1951), and multi-instrumentalist Peter Apfelbaum (b. 1960).

- Elena Ayodele Pinderhughes (b. 1995) — Californian flutist, songwriter, and singer who has performed with bassist Esperanza Spalding (b. 1984), saxophonist Joshua Redman (b. 1969), and trumpeter Christian Scott (b. 1983).

(Click on photo for source than move to number twenty out of forty-four)

- Watch her solo improvisation immediately following Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah's (b. 1983) opening for his NPR Music Tiny Desk Concert, October 9, 2015.

(Photo taken March 2, 2013 in Bath, Maine

by Paul VanDerWerf using Photoshop's Artistry 4: Graphic and Grunge Actions then colorized by PoJ.fm)

- Grace Kelly (b. 1992) — American musician, singer, entertainer, songwriter, arranger, and primarily alto saxophonist. A seven-time winner of the DownBeat Critics Poll who plays on the house band led by Jon Batiste (b. 1986) for "The Late Show with Stephen Colbert."

Born Grace Chung, Kelly was named one of Glamour magazine's Top 10 College Women in 2011. In 2014, Kelly recorded her EP, "Working For The Dreamers." She was featured in the December 2015 issue of Vanity Fair as a notable millennial in the jazz world. In her eighth year in a row being named to the Downbeat Critics Poll, Kelly won the 2016 64th Annual Downbeat Critics Poll "Rising Star Alto Saxophone." Grace's 10th album release as a leader, "Trying To Figure It Out" (2016 PAZZ), was voted the number-two Jazz Album of the Year in the 2016 DownBeat readers' poll.

Kelly was mentored by saxophone legend Lee Konitz (1927–2020) and has performed with Wynton Marsalis (b. 1961) as well as with saxophonist Phil Woods (1931–2015).

Watch her killer New Orleans inspired danceable tune "Fish & Chips" with baritone saxophonist Leo P. (born 1991).

- Brandee Younger (b. 1983) — American composer, educator, and harpist in jazz, classical, and pop active since 2006.

While still a twenty-three year old NYU graduate student, saxophonist Ravi Coltrane recruited her to play for his mother's memorial service, harpist Alice Coltrane (1937–2007). Younger studied with alto saxophonist Jackie McLean (1931–2006) and has performed with Jack DeJohnette (b. 1950), Charlie Haden (1937–2014), Lauryn Hill (b. 1975), and Common (b. 1972).

- Hailey Niswanger (b. 1990) — American composer and saxophonist who has toured with Esperanza Spalding’s (b. 1984) Radio Music Society and performed with Ralph Peterson Jr. (1962–2021), The Soul Rebels, and Terri Lyne Carrington’s (b. 1965) Mosaic Project. Niswanger recorded with the Wolff & Clark Expedition in 2015 led by pianist Michael Wolff (b. 1952) and drummer Mike Clark (b. 1946).

(Photo on far right by Alan Nahigian)

(Victoria Theater on October 23, 2019 in Oslo, Norway 🇳🇴 colorized)

- Linda May Han Oh (b. 1984) — Australian jazz bassist and composer who DownBeat magazine named #1 Acoustic Bass Rising Star (2010). She has recorded and performed with Lee Konitz (1927–2020), Kenny Barron (b. 1943), Geri Allen (1957–2017), Terri Lyne Carrington (b. 1965), Joe Lovano (b. 1952), and Steve Coleman (b. 1956). Oh is a member of Cuban pianist Fabian Almazan’s (b. 1984) trio with drummer Henry Cole (b. 1979).

(All photos in composite individually taken by Peter Tea on June 6 & 7, 2011 while on tour in Australia 🇦🇺 and New Zealand 🇳🇿.)

Ten Rising Women Instrumentalists from 2018[edit]

![]() Rusty Aceves, "Ten Rising Women Instrumentalists You Should Know," "On the Corner," SFJazz.org, March 7, 2018. Accessed July 30, 2022. The ten instrumentalists include:

Rusty Aceves, "Ten Rising Women Instrumentalists You Should Know," "On the Corner," SFJazz.org, March 7, 2018. Accessed July 30, 2022. The ten instrumentalists include:

- 🔆 Mary Halvorson (b. 1980) American jazz guitarist who has led over twenty albums and worked with Anthony Braxton, Yo La Tengo, and a trio project with fellow visionary guitarists Elliott Sharp and Marc Ribot.

- 🔆 Yissy García (b. 1987) — Cuban-born drummer, composer and Afro-Cuban jazz and rock stylist who has played with Esperanza Spalding, Roy Hargrove, and Dave Matthews. Listen to her band Bandancha play three songs: "Última Noticia," "Universo," and "Te cogió lo que anda" from June 15, 2018.

- 🔆 Sasha Berliner(b. 1998) American jazz vibraphonist, composer, and social activist. — Berliner is a San Francisco native who began on drums at eight and attended the Oakland School for the Arts before becoming a two-year member of the SFJAZZ High School All-Stars. Berliner was a student of Stefon Harris and Matt Wilson at the New School in New York. She has worked with Beck, Vijay Iyer, Terri Lyne Carrington, Ravi Coltrane, and Jane Ira Bloom, and released her full-length debut album, "Azalea," in 2018.

- 🔆 Yazz Ahmed (b. 1983) British-Bahraini trumpeter — Ahmed has collaborated with artists including Radiohead and Lee “Scratch” Perry, and has created a personal approach born of her Middle Eastern roots and British upbringing described as “psychedelic Arabic jazz.” Originally inspired by her jazz musician grandfather, she has become a major voice in the exploding London jazz scene that includes Shabaka Hutchings, Sons of Kemet, and Yussef Kamaal, releasing her second album, La Saboteuse.

- 🔆 Camille Thurman (b. 1986) American jazz saxophonist and vocalist — Already acclaimed by DownBeat as a “rising star,” Thurman received the Lincoln Center Award for Outstanding Young Artists and was a two-time winner of the ASCAP Herb Alpert Young Jazz Composers Award. She has performed alongside Dianne Reeves, Wynton Marsalis & the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, Erykah Badu, and Roy Haynes. She has recorded four albums including a recent live session featuring Mark Whitfield, Ben Allison, and Billy Drummond.

- 🔆 Nubya Garcia (b. 1991) British jazz tenor saxophonist — Among the vanguard of the British scene, London-based Garcia brings her Caribbean heritage into an innovative approach, mixing spiritual, afro-futurist jazz with hip-hop rhythms and global influences. She received the Steve Reid InNOVAtion Award and played on BBC DJ Gilles Peterson’s new Brownswood Recordings compilation "We Out Here." She released her EP "When We Are" in March 2018.

- 🔆 Allison Au (b. 1985) Canadian jazz alto saxophonist, flautist, and composer/arranger out of Toronto — Au has established herself as a significant instrumentalist, composer, and arranger who has released two self-produced albums of original material that received two Juno Award nominations and a Best Jazz Album of the Year win for her 2016 album "Forest Grove." Her longstanding quartet won the 2017 Montreal Jazz Festival TD Grand Prix de Jazz and was a 2017 finalist for the Toronto Arts Foundation Emerging Jazz Artist Award. She won the Duke Ellington Scholarship for Outstanding Achievement and the Ron Collier Memorial Scholarship for Outstanding Achievement in Arranging. As an arranger, she has covered many genres, including jazz, Latin jazz, Salsa, Cumbia, Merengue, and contemporary improvisational music in instrumentation formats ranging from big band ensembles to small jazz combos or even string ensembles.

- 🔆 Jaimie Branch (b. 1983) American jazz trumpeter, composer, and recording engineer working in free jazz and improvised music based in Brooklyn, New York. — Branch was listed by Rolling Stone’s’ June 2017 list of “Ten New Artists You Need to Know.” Branch uses free improvisation and cutting edge experimentation working with bass legend William Parker and saxophonist Ken Vandermark, as well as with pop acts Arcade Fire and TV on the Radio. Her debut album "Fly or Die" with cellist Tomeka Reid and drummer Chad Taylor was released in 2017.

- 🔆 Tomeka Reid (b. 1977) American jazz cellist — Chicago based Reid is a fiercely creative improvisor and composer who has played with Roscoe Mitchell, Anthony Braxton, Tyler Ho Bynum, Nicole Mitchell, George Lewis and Myra Melford. Reid often works with Chicago’s legendary AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians) while also playing in a quartet with guitarist Mary Halvorson, bassist Jason Roebke, and drummer Tomas Fujiwara.

- 🔆 Sharel Cassity (prounced "Sha-Relle") (b. 1978) American jazz saxophonist, multi-reedist, composer, recording artist, bandleader, and educator. — Chicago based Cassity graduated from Julliard in 2007. She has been on DownBeat’s Critics Poll for Rising Star Saxophonist for a decade. Often leading a quartet, she has recorded five albums as a leader, including the recent two"Elektra" and "Evolve." The saxophonist has played with Roy Hargrove, Cyrus Chestnut, Aretha Franklin, Vanessa Williams, K.D. Lang, Fantasia, Trisha Yearwood, Seth MacFarland (Family Guy), Ruben Blades, DJ Logic, Natalie Merchant (on her recording "Paradise is Here"), Herbie Hancock, Wynton Marsalis, Dee Dee Bridgewater, Christian McBride, and Natalie Cole. Sharel was lead alto in the Diva Jazz Orchestra from 2007–2014 and performed in Wynton Marsalis's Broadway musical "After Midnight." She is a regular member of the Dizzy Gillespie Latin Experience, Nicholas Payton TSO, Cyrus Chestnut Brubeck Quartet, and the Jimmy Heath Big Band. She has toured twenty-four countries performing at leading venues like the Newport Jazz Festival, Monterey Jazz Festival & the North Sea Jazz Festival.

Sharel appears in publications "I Walked with Giants" by Jimmy Heath, "AM Jazz: Three Generations Under the Lens" by Adrianna Mateo and "Freedom of Expression: Interviews with Women in Jazz" by Chris Becker.

An alumni of IAJE Sisters in Jazz, Betty Carter's Jazz Ahead, and the Ravinia Summer Residency, Sharel has received DownBeat Student Music Awards for Best Jazz soloist, Composition, and Ensemble.

As classical pianist, Sharel placed third in the Disney International Piano Concerto Competition at the age of 10, among many other collegiate and state piano competitions. An accomplished classical saxophonist, Sharel was offered a full scholarship to North Texas State University for classical saxophone.

Currently, Cassity has a temporary full-time position at the University of Wisconsin-Madison as Professor of Saxophone for the Fall 2019 semester. Additionally, she has three adjunct positions in the Chicago area at Elgin Community College, Columbia College, and DePaul University. Between 2016–17 Sharel taught internationally as the Woodwind Professor at Qatar Music Academy in Doha, Qatar.

Women in Jazz and Beyond in the 21st Century[edit]

Erica von Kleist (b. 1982) — flutist, saxophonist, educator, composer, and bandleader. Von Kleist went to the Manhattan School of Music, then Juilliard, graduating with a Bachelor’s degree in jazz in 2004. She toured with the Afro Latin Jazz Orchestra and appeared on two of their albums nominated for Grammy Awards. She has performed or recorded with Wynton Marsalis and the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, Darcy James Argue's Secret Society, Chris Potter, Bebo Valdez, Cachao, Celia Cruz, Kristin Chenoweth, and Seth MacFarlane. Her debut album was "Project E" (2005), followed by "Erica von Kleist and No Exceptions" (2010), then "Alpine Clarity" (2014). She has been voted many times as a “Rising Star” and “Critic’s Pick” in DownBeat magazine.

Yazz Ahmed (b. 1983) a British-Bahraini trumpeter, flugelhornist and composer whose music mixes Arabic and Western influences. She has worked with Toshiko Akiyoshi, Rufus Reid, John Zorn, Ash Walker, the London Jazz Orchestra, and has recorded and performed with Radiohead, Lee Perry, ABC, Swing Out Sister, Joan as Police Woman, Tarek Yamani and Amel Zen, and the band These New Puritans. Her albums include "Finding My Way Home" (Suntara, 2011), "La Saboteuse" (2015) and "Polyhymnia." See her discography.

Sheila Maurice-Grey (b. 1991) — British trumpeter, vocalist, and visual artist. Also known as Ms. Maurice. Bandleader of KOKOROKO and plays with jazz septet Nérija, who were nominated for Jazz Fm Breakthrough Act 2016 and Parliamentary Jazz Newcomer of Year 2017 winner. She has performed with the likes of SOLANGE, KANO on the ‘Jool’s Holland Show’ and ‘The Mercury Prize 2016,’ and features on Little SIMZ’s album ‘Stillness in Wonderland.’

Nigerian saxophonist based in Britain Camilla George (b. 1983).

British fusion and jazz guitarist Shirley Tetteh (b. 1990).

British pianist Sarah Tandy. yeah.

Sarah Wilson (b. 1968) — American trumpeter, vocalist, and composer whose music uses avant pop, Afro-Latin grooves, indie rock and post-bop. Wilson’s compositions incorporate influences from theater, jazz, dance, and film. Her third album released in 2021 was "Kaleidoscope" (Brass Tonic Records)

Earlier albums include "Music for an Imaginary Play" (2006)

and "Trapeze Project" (2010)

Lis Wessberg (b. 1967) — Danish trombonist with thirty year career as sidewoman on over forty albums.

— See and hear her official video for the first track titled "The Strip" off of her debut release in 2021 Yellow Map.

.

— See and hear an eight minute live version of "The Strip."

Women in Jazz Internet Resources[edit]

Popular websites that feature women jazz musicians and their information:

![]() YouTube's Jazz Women videos

YouTube's Jazz Women videos

![]() Women in Jazz South Florida

Women in Jazz South Florida  started in 2007.

started in 2007.

![]() Jazz at Lincoln Center (http://www.jazz.org/category/music/women-in-jazz/)

Jazz at Lincoln Center (http://www.jazz.org/category/music/women-in-jazz/)

![]() The Jazz Gallery (http://www.jazzgallery.org/category/women-in-jazz/)

The Jazz Gallery (http://www.jazzgallery.org/category/women-in-jazz/)

![]() Jazz Services (http://jazzservices.org.uk/women-in-jazz-2/)

Jazz Services (http://jazzservices.org.uk/women-in-jazz-2/)

![]() Jazz Society of Oregon (http://jazzsocietyoforegon.org/women-in-jazz/)

Jazz Society of Oregon (http://jazzsocietyoforegon.org/women-in-jazz/)

Laurie Frink (1951–2013) American jazz trumpeter, jazz educator, and counselor.

Laurie Frink (1951–2013) American jazz trumpeter, jazz educator, and counselor.

![]() German born pianist Dr. Monika

Herzig (b. 1964), "Equal Access: Women in jazz come together, Allegro, Volume 122, No. 1, January, 2022. Accessed January 4, 2022.

German born pianist Dr. Monika

Herzig (b. 1964), "Equal Access: Women in jazz come together, Allegro, Volume 122, No. 1, January, 2022. Accessed January 4, 2022.

![]() Kai EL' Zabar (Executive Director of the eta Creative Arts Foundation in Chicago, IL as of July 2019), "Eleven Jazzy Divas Celebrate Women's History Month," The Chicago Defender, March 9, 2016. The featured vocalists include Joan Collaso, Bobbi Wilsyn, Tecora Rogers, Yvonne Gage, Maggie Brown, Julia Huff, Margaret Murphy-Webb, Lynne Jordan, Frieda Lee, Greta Pope, and Felena Bunn singing the music of Chaka Khan, Nancy WIlson, Ella Fitzgerald, Dianne Reeves, Phyllis Hymen, Abbie Lincoln, Lena Horne, Eartha Kitt and more.

Kai EL' Zabar (Executive Director of the eta Creative Arts Foundation in Chicago, IL as of July 2019), "Eleven Jazzy Divas Celebrate Women's History Month," The Chicago Defender, March 9, 2016. The featured vocalists include Joan Collaso, Bobbi Wilsyn, Tecora Rogers, Yvonne Gage, Maggie Brown, Julia Huff, Margaret Murphy-Webb, Lynne Jordan, Frieda Lee, Greta Pope, and Felena Bunn singing the music of Chaka Khan, Nancy WIlson, Ella Fitzgerald, Dianne Reeves, Phyllis Hymen, Abbie Lincoln, Lena Horne, Eartha Kitt and more.

![]() Giovanni Russonello, "10 Women in Jazz Who Never Got Their Due," New York Times, published April 22, 2020, updated May 9, 2020.

Giovanni Russonello, "10 Women in Jazz Who Never Got Their Due," New York Times, published April 22, 2020, updated May 9, 2020.

The ten women list includes:

- Lovie Austin, pianist (1887–1972)

- Lil Hardin Armstrong, pianist (1898–1971)

- Valaida Snow, trumpeter (1904–1956)

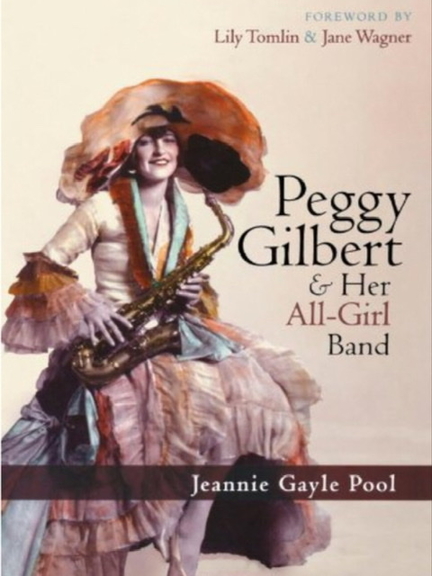

- Peggy Gilbert, saxophonist (1905–2007)

- Una Mae Carlisle, pianist (1915–1956)

- Ginger Smock, violinist (1920–1995)

- Dorothy Donegan, pianist (1922–1998)

- Jutta Hipp, pianist (1925–2003)

- Clora Bryant, trumpeter (1927–2019)

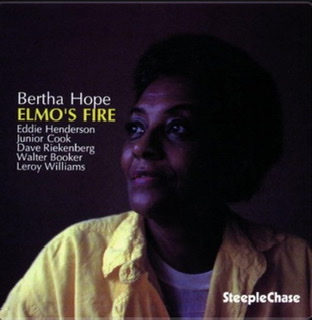

- Bertha Hope-Booker, pianist (1936– )

by Mike Flynn at Jazzwise.com webzine, February 17, 2020.

by Mike Flynn at Jazzwise.com webzine, February 17, 2020.

- Louise "Lou" Paley and Nina Fine are addressing the gender imbalance in jazz in the United Kingdom in practical and positive ways.

![]() Cecilia Björck and Åsa Bergman, "Making Women in Jazz Visible: Negotiating Discourses of Unity and Diversity in Sweden and the US," IASPM Journal, Vol 8, No 1 (2018).

Cecilia Björck and Åsa Bergman, "Making Women in Jazz Visible: Negotiating Discourses of Unity and Diversity in Sweden and the US," IASPM Journal, Vol 8, No 1 (2018).

Abstract: “The aim of this article is to examine responses to a project that aspires to further gender-equal jazz scenes in Sweden and the US. The project brought together actors at various levels of the industry: cultural agencies, commercial organizers, activists, and artists. Our analysis—with special focus on resistance-voiced—is based on observations, interviews with organizers, and a documentary about the project. The project’s central ambition was to make women in jazz visible in order to change a structural imbalance where men still take up most of the space on stage. This ambition was, however, complicated as different actors resisted a female–male binary, and thus the very idea of “women in jazz.” The resistance was played out through gender equality discourses of either unity or diversity, varying in relation to national context and generation. The article also discusses visibility as a central but also problematic aspect for gender equality efforts in music.”[71] (bold and bold italic not in original)

![]() By 1999, little had changed in mainstream jazz historiography as evidenced by the continued absence of many prominent jazzwomen from the jazz sections of the Reader’s Guide to Music History, Theory, and Criticism (1999) edited by Jeremy Steib.

By 1999, little had changed in mainstream jazz historiography as evidenced by the continued absence of many prominent jazzwomen from the jazz sections of the Reader’s Guide to Music History, Theory, and Criticism (1999) edited by Jeremy Steib.

![]() Linda Dahl. Stormy Weather: The Music and Lives of a Century of Jazzwomen. New York: Limelight Editions, 1989. In addition to an impressive collection of biographical information and an extensive discography, Dahl includes chapters such as “Equal time: Beyond the Fraternity, Toward Community” and “Building a Support System,” which further contextualize female participation and give voice to a budding movement toward the normalization of gender in jazz.

Linda Dahl. Stormy Weather: The Music and Lives of a Century of Jazzwomen. New York: Limelight Editions, 1989. In addition to an impressive collection of biographical information and an extensive discography, Dahl includes chapters such as “Equal time: Beyond the Fraternity, Toward Community” and “Building a Support System,” which further contextualize female participation and give voice to a budding movement toward the normalization of gender in jazz.

![]() Handy, D. Antoinette. Black Women in American Bands and Orchestras, Second Edition. Lantham, Mass. and Kent: Scarecrow Press, 1998.

Handy, D. Antoinette. Black Women in American Bands and Orchestras, Second Edition. Lantham, Mass. and Kent: Scarecrow Press, 1998.

![]() Sally Placksin. American Women in Jazz: 1900 to the Present, Their Words, Lives, and Music. New York: Wideview Books, 1982. A well-researched collection profiling over sixty jazzwomen.

Sally Placksin. American Women in Jazz: 1900 to the Present, Their Words, Lives, and Music. New York: Wideview Books, 1982. A well-researched collection profiling over sixty jazzwomen.

![]() Susan Cavin, “Missing Women: On the Voodoo Trail to Jazz,” Journal of Jazz, Studies Vol. 3, no. 1, Fall 1975, 4–27.

Susan Cavin, “Missing Women: On the Voodoo Trail to Jazz,” Journal of Jazz, Studies Vol. 3, no. 1, Fall 1975, 4–27.

![]() Angela Y. Davis, Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude "Ma" Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday,

Angela Y. Davis, Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude "Ma" Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday,  first Vintage Books edition, February 1999. Published in the United Slates by Vintage Books, a division of Random Home, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 1998.

first Vintage Books edition, February 1999. Published in the United Slates by Vintage Books, a division of Random Home, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 1998.

![]() Jeffrey Taylor, “With Lovie and Lil: Rediscovering Two Chicago Pianists of the 1920s” (conference paper), Society for Music Theory, Annual Meeting, Columbus, OH, November 1, 2002. Reprinted in Big Ears: Listening for Gender in Jazz Studies, Edited by

Nichole T. Rustin & Sherrie Tucker, Durham: Duke University Press, 2008.

Jeffrey Taylor, “With Lovie and Lil: Rediscovering Two Chicago Pianists of the 1920s” (conference paper), Society for Music Theory, Annual Meeting, Columbus, OH, November 1, 2002. Reprinted in Big Ears: Listening for Gender in Jazz Studies, Edited by

Nichole T. Rustin & Sherrie Tucker, Durham: Duke University Press, 2008.

![]() Charles Chamberlain. “The Goodson Sisters: Women Pianists and the Function of Gender in the Jazz Age.” The Jazz Archivist, vol. XV (2001), 1–9.

Charles Chamberlain. “The Goodson Sisters: Women Pianists and the Function of Gender in the Jazz Age.” The Jazz Archivist, vol. XV (2001), 1–9.

![]() "The Girls in the Band" Female Jazz Instrumentalists and their websites

"The Girls in the Band" Female Jazz Instrumentalists and their websites

![]() ArtVilla.com's Women Jazz Musicians Instrumentalists and Vocalists

ArtVilla.com's Women Jazz Musicians Instrumentalists and Vocalists

![]() "A DIY Guide to the History of Women in Jazz" by Laura Pelligrinelli at NPR'S A BLOG SUPREME, May 10, 2013.

"A DIY Guide to the History of Women in Jazz" by Laura Pelligrinelli at NPR'S A BLOG SUPREME, May 10, 2013.

![]() "Ireland’s jazz scene continued to grow in strength and diversity in 2019: Smaller regional festivals were major successes while a number of important projects were led by Irish and Irish-based women," The Irish Times News, Saturday, Dec 7, 2019.

"Ireland’s jazz scene continued to grow in strength and diversity in 2019: Smaller regional festivals were major successes while a number of important projects were led by Irish and Irish-based women," The Irish Times News, Saturday, Dec 7, 2019.