EmT9. Is jazz dead?

Contents

- 1 Discussion

- 2 Introduction

- 3 Authors assess the death of jazz

- 4 Jeff Winbush's six reasons for jazz's decline

- 5 Print or online jazz magazines

- 6 Active jazz clubs

- 7 Active jazz festivals

- 8 Jazz Appreciation Month (JAM) and International jazz day

- 8.1 Jazz around the world

- 8.2 Response to (Winbush 1) on the current status of jazz

- 8.3 Response to (Winbush 2) on the fragmentation of jazz

- 8.4 Response to (Winbush 3) on hearing jazz

- 8.5 Response to (Winbush 4) on the state of jazz education

- 8.6 Response to (Winbush 5) on America's ignorance of jazz

- 8.7 Response to (Winbush 6) on jazz being a snob musical genre

- 9 Musician's reveal interest in topic of jazz's death

- 10 Evaluating why jazz is dead could be true

- 11 Reasons jazz died in 1959

- 12 Reasons jazz did NOT die in 1959

- 13 Critique of Nicholas Payton's remarks on the death of jazz

- 14 Evaluating why jazz is dead is false

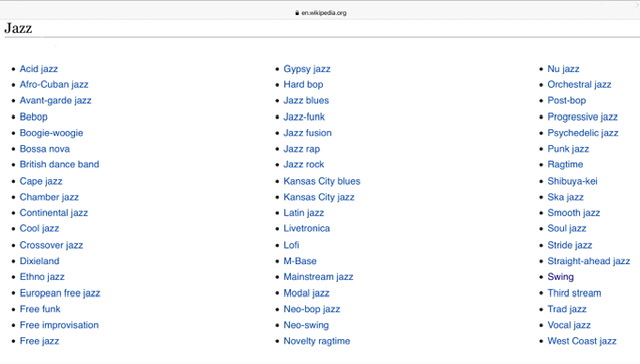

- 14.1 Styles of music

- 14.2 Seven problems with jazz being dead

- 14.3 What could count as the death of jazz?

- 15 Definitions for dead

- 16 Jazz is not dead yet

- 17 Can jazz die?

- 18 Summary of Evaluations

- 19 Internet Resources on jazz is dead

- 20 NOTES

Discussion[edit]

Introduction[edit]

Overview of "Is jazz dead?"

NOTE: Click on any of the blue text to hyperlink to that section of this post.The question of whether jazz can die is explored. Positive responses are given to Jeff Winbush's six reasons for jazz's decline. Numerous authors proclaim or deny the death of jazz. Musician's reveal their interests in the question of whether or not jazz is dead. An evaluation of why jazz is dead could be true is followed by reasons jazz could have died in 1959 and then reasons why jazz did not die in 1959 with examples of great jazz from America for every decade from the 1960s to the present. Next, a presentation and critique of Nicholas Payton's remarks on the death of jazz precedes Payton later walking back virtually all of his negative claims against jazz. Further reasons are provided explaining why it is false that jazz is dead considering the numerous styles of music that remain jazz. Seven problems are proposed for the claim that jazz is dead. The question of what could count as the death of jazz is supplied with one author arguing that jazz is mostly only dead on the radio and television. The many different concepts of death are defined with their possible relationships to jazz's death examined. Difficulties with definitions for being alive are given with examples of entities that are alive without being biological organisms. Definitions for dead show that jazz is not dead yet with examples of live and recorded streaming jazz performances done in 2020. Next, what is learned in a jazz instructional setting? Reasons for and against the possibility of the death of jazz with an evaluation and critique of the JCNAD (jazz cannot be alive or dead) argument and the MCND (music cannot die) argument. Reasons are given for how jazz can die. Lastly, internet resources arguing both for and against the death of jazz are listed.

Authors assess the death of jazz[edit]

“Others argued that jazz [in 1926], having reached its peak, was simply not making any new contributions to music. André Messager, the composer who had previously startled colleagues by announcing his adoration of jazz, soon noted, “It seems to me that if ‘jazz’ is not yet old-fashioned, it is not progressing.”[1] “Jazz, argued another composer in the mid-1930s, “from the point of view of orchestral arrangements has not made much progress for twenty years!”[2] (bold and bold italic not in original)

In "Jazz Has Got Copyright Law and That Ain't Good" the Harvard Law Review[3] author(s) justify the claim that jazz is dying:

"Jazz is in trouble. Even if the music is not dead, "a lot of people think jazz is dying." Efforts at diagnosis and attempts to revive the music are difficult because it faces a complicated predicament: the music is suffering both popularly and creatively. Jazz's fall from popularity has been well-documented. Jazz now accounts for less than three percent of total record sales. It does not dominate or dictate pop culture as it once did, and its primary outlet is the small jazz club. To make matters worse, the music seems to be attracting an older following: the median age of those attending jazz events in 1992 was thirty-seven, and by 2002 it had risen to forty-three. Jazz musicians are no longer celebrities, lauded for their genius and inventiveness. Rather, they "are scarcely recognised by anyone outside the hard-core coterie of followers.""

"The goal of this Note is to show that, while copyright law may not have caused the precipitous end of jazz as a commercially viable and ever-innovative music, it will not stop jazz's descent with its ill-fitting doctrines. This Note assumes that jazz is a "useful Art" worth protecting and promoting, and argues that those creating and deciding copyright law have failed to meet their constitutional charge "[t]o promote the Progress of ... [this] useful Art." The current copyright scheme discourages jazz creation, provides scant protection for the improvised material and performances of jazz musicians, and diverts royalties and performance fees away from the musicians who deserve them. By privileging the composers of the simple underlying tunes that comprise the vocabulary of the jazz language, copyright discourages vital reinterpretation. Finally, through a strained conception of authorship and originality that diverts copyright protection and benefits away from deserving musicians, copyright discourages young musicians from pursuing jazz." (bold and bold italic not in original)

Raising the issue of whether jazz is dying and then arguing it cannot die is the author of "Jazz and Its Evolution" Gourav Biswas.

“FUTURE OF JAZZ: Terry Teachout at the Wall Street Journal has sounded the alarm over the serious decline in the popularity of jazz. Evidently the audience for jazz in America is both aging and shrinking at a staggering rate, making it resemble the folks who dutifully take their classical-music vitamins. Jazz no longer seems to speak to young people, which doesn't bode well for the future of the genre. And it is precisely because jazz is now widely viewed as a high-culture art form that its makers must start to grapple with the same problems of presentation, marketing and audience development as do symphony orchestras, drama companies and artmuseums a task that will be made all the more daunting by the fact that jazz is made for the most part by individuals, not established institutions with deep pockets.

“Teachout offers no solutions, except that jazz musicians must now figure out a way to make a case for the beauty of their music. The glam-based cornetist Muggsy Spanier, who found his life's vocation by listening as a youth to Louis Armstrong, once punched critic Leonard Feather an advocate of modern jazz in the chops a half-century or so ago during the war between the "moldy figs" and the beboppers. Mugsy resented being consigned to a museum.”“ . . . Brian Gilmore in the December 2002 issue of The Progressive in which he quoted Reuben Jackson, the Smithsonian Institution's Ellington archivist, declaring jazz to be "moribund." My dictionary's definition of moribund: "having little or no vital force left."”

“Pink Floyd guitarist Dave Gilmore, however, believes that "free jazz" will rescue the music from its doldrums and jazz may even become political again, as it was in the '60s and '70s, when, he writes, it "thundered about injustice."”

“Jim Hall, the 72-year-old guitarist and composer laughs on asking if he feels jazz is "moribund." He says, "How can it be? The spirit of this music ain't going to die unless the world blows up." Hall, who never stops growing musically, can and does play with ease and authority with musicians of all styles and ages. "I've played," he said, "what we call jazz with people all over the world with whom I couldn't have a conversation.”[4] (bold not in original)

English historian and jazz writer Eric Hobsbawm (has written under the pseudonym of Francis Newton)

“Such was the reality of jazz in the 1960s and much of the 1970s, at any rate in the Anglo-Saxon world. There was no market for it. According to the Billboard International Music Industry Directory of 1972 a mere 1.3 per cent of records and tapes sold in the U.S.A. represented jazz, as against 6.1 per cent of classical music and 75 per cent rock and similar music. Jazz clubs went on closing, jazz recitals declined, avant-garde musicians played for each other in private apartments, and the growing recognition of jazz as something which belonged to official American culture, while providing a welcome subsidy to uncommercial musicians through schools, colleges and other institutions, reinforced the youthful conviction that jazz now belonged to the world of the adults. Unlike rock, it was not their own music.”[5] (italics are author's; bold not in original)

English poet and jazz enthusiast Philip Larkin finds jazz may be dying.

“It seems to me ironic to find Cannonball [Adderley] lamenting recently in Melody Maker that while we have a generation of kids who are raised on a constant diet of music, they don't listen to jazz, and jazz is dying in consequence.[6] (bold not in original)

Tenor saxophonist Stan Getz (1927–1991) had a fifty year musical career. Right before his death of liver cancer in 1991 he was asked about the state of jazz. He denies that jazz is dead and claims it has only been going through some "bad periods" where he appears to blame politically hostile music.

“Cash Box: Are you optimistic about the state of jazz?

Getz: Most definitely, I always have been. There's always shit about, jazz is dead. It's not dead, it's just gone through some bad periods, that's all. When that hate music came on the scene, that politically oriented music, that was expressing political views — sure, I wouldn't listen to that either, why would the people listen to it, man. Any kind of art form is put on the earth to enhance life, to make it beautiful. You don't want to read too much in it, you just want to enjoy it. Don't analyze this shit to death.”[7] (bold and bold italic not in original)

![]() Report on Decline in Jazz Sales

Report on Decline in Jazz Sales

“As its title "The End of Jazz," (from The Atlantic (November, 2012) implies, though, Benjamin Schwarz aims to measure the music for its coffin, as the American songbook—which has not much budged since about 1952—and jazz fade out like tragic lovers separated by distance. Schwarz sees “no reason to believe that jazz can be a living, evolving form decades after its major source—and the source that linked it to the main currents of popular culture and sentiment—has dried up.” Jazz, like the songbook, Schwarz writes, “is a relic.” [8] (bold and bold italic not in original)

“By 1922, Vogue contributor Clive Bell claims, “Jazz is dead—or dying, at any rate—and the moment has come for someone who likes to fancy himself wider awake than his fellows to write its obituary notice.”[9] But jazz is a rebellious teenager that will live out its life to the fullest extent as it grows up in the 20th century of America.

The question—Is Jazz dead?—is not a new one. It has been raised in every era of jazz as new styles come to replace old ones. It comes from a myopic view of the music, a desire to cling to the past, and a misunderstanding of how music and art change over time. Neither critics nor the masses should make judgments about its health without first examining its history and craft.

When I asked Brian Kane, a professor in the Department of Music at Yale College, he said, “Jazz is dead if one thinks about a certain set of narrow conventions to define it. If it has to look like jazz of the past, jazz is dead.” I believe this is the root of the popular belief that jazz is dead. People don’t really know what jazz was, much less what it is.”[10] (bold and bold italic not in original)

“In a 1983 interview, [Wynton Marsalis] said, “Everyone was saying jazz was dead because no young black musicians wanted to play it anymore.” For Marsalis, the music’s path since 1960 abandoned its racial roots, authenticity and sense of community.”[11] (bold not in original)

“In Blue, Eric Nisenson said, "The cry that 'jazz is dead' has been so ubiquitous throughout jazz history that it has almost become a tradition in itself. John P. McCombe correctly states that this is only half of the equation, for "tales of jazz's demise usually feature the promise of jazz rebirth." In his essay "Eternal Jazz: Jazz Historiography and the Persistence of the Resurrection Myth," McCombe suggests, "the jazz master-narrative of resurrection is part and parcel of jazz's academic apotheosis." Among the death/rebirth scenarios in jazz history are the closing of Storyville in 1917, and the subsequent birth of a new scene in Chicago in the early 1920s; the supplanting of 'traditional' jazz by swing in the 1930s; the "Moldy Figs versus Moderns" debate as the swing era died out at the onset of the Bebop revolution; the "New Thing" that emerged just as hard bop was getting stale; the rise of jazz/rock fusion at the expense of acoustic jazz; and most recently, the debate over Wynton Marsalis and the neocons. At each juncture of this narrative, critics weighed in with warnings of jazz's death, using such phraseology as "nihilistic, cynically destructive" (Rudy Blesh, on swing), "and irresponsible exploitation of technique in contradiction of human life as we know it" (Philip Larkin, on Bebop), or "a horrifying demonstration of what happens to be a growing 'anti-jazz' trend" (Neil Leonard, on free jazz). Add Ken Burns to the list of doomsayers. In the final episode of Jazz, his narrator states "for a long time [in the 1970s], the real question would become whether this most American of art forms could survive in America at all."[12] (bold and bold italic not in original)

Jeff Winbush's six reasons for jazz's decline[edit]

Jazz critic, journalist, blogger, & IT Professional Jeff Winbush with a Masters in Music from Texas State University (2000) gives six reasons for the decline of jazz. He has a point! Nevertheless, to at least a few of his reasons for jazz's decline one can supply some positive replies, as seen below.

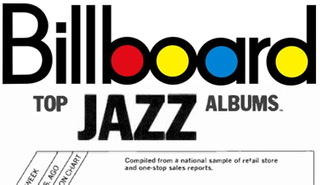

(Winbush 0): If jazz continues its slow, sad slide into musical irrelevance, pretty soon you'll only be able to find it in museums and a line or two if that in history books.

(Winbush 1): The most popular forms of jazz barely qualify as jazz. This week's Billboard contemporary jazz charts has Tony Bennett's collaboration with Lady Gaga is #2 and Annie Lennox follows at #3. If you want to call Bennett a jazz singer, I won't kick, but Gaga and Lennox? Pop stars slumming gets a definite "No."(Winbush 2): Jazz is highly fragmented. Contemporary-straight ahead jazz fans into a Wynton Marsalis don't have much use for avant-garde, experimental types like a Cecil Taylor or John Zorn and both loathe "smooth" jazz as practiced by a Kenny G. or Dave Koz. The problem is jazz is such a tiny portion of overall music sales (down to under 2 percent in 2014), there's really no place for elitism and exclusion. There simply isn't enough slices of the pie for anyone to be thumbing their noses at the subdivisons of jazz.

(Winbush 3): The collapse of the record labels and radio stations still playing jazz as a format have sped the decline of the genre's popularity. If you can't hear it on the radio, you're probably not going to find out about new and older artists still making music and clubs aren't going to book jazz artists and you're not going to able to find venues to hear live jazz. As far as TV goes, fuhgeddabouit. My, what a tangled web we weave.

(Winbush 4): Schools are chopping their music classes and there goes a feeder system for kids who aspire to play something more complex than turntables and ProTools. If you can't hear jazz, see jazz or play jazz, where's the next generation of new blood coming from to replace the old blood?

(Winbush 5): America is ignorant of its jazz history and heritage which is why so many musicians spend their summers touring Europe and Japan. If you're not playing across the pond, you had better find a side gig as a session musician or educator to pay the bills.

(Winbush 6): Jazz has made itself a genre for snobs, hipsters and pseudo-intellectuals. It needs to find a way to attract the masses.”[13] (Winbush numbering in parentheses and bold font not in original)

While all six points above are correct to varying degrees some are not as dire as Jeff Winbush fears. Are there some positive contrary responses supportive of jazz's continuation?

Positive responses to Winbush's six reasons for the decline of jazz[edit]

Consider Winbush's six points in green font followed by a positive response in blue font.

Prior to listing his six points explaining why jazz has declined, Jeff Winbush claims at (Winbush 0): “If jazz continues its slow, sad slide into musical irrelevance, pretty soon you'll only be able to find it in museums and a line or two if that in history books.”

Response to (Winbush 0) on the musical irrelevance of jazz[edit]

Winbush refers to the possibility of jazz being or soon becoming musically irrelevant.

The word "irrelevant" is an adjective that literally means not relevant. Dictionary.com continues the definition of "irrelevant" by including the meanings of when something is not applicable or pertinent. Something is applicable when it can be applied. In contrast, something is pertinent when it pertains or relates directly and significantly to the matter at hand. To get a further sense of the meanings associated with being "irrelevant," Dictionary.com includes all of these: not important, extraneous, immaterial, inappropriate, inconsequential, insignificant, pointless, trivial, unimportant, unnecessary, unrelated, foreign, garbage, impertinent, inapplicable, inapposite, inapt, inconsequent, out of order, out of place, outside.

For jazz to become musically irrelevant, it would have to fall under these categories. It is often easier to prove a positive claim over a negative one. For example, instead of asking how many dogs do not listen to their owner's commands, one can ask to find dogs that listen to commands and act appropriately. Instead of asking about irrelevance, ask if jazz currently is musically relevant.

So, is jazz currently relevant to the music scene? Yes, that is the correct answer. What is the evidence in favor?

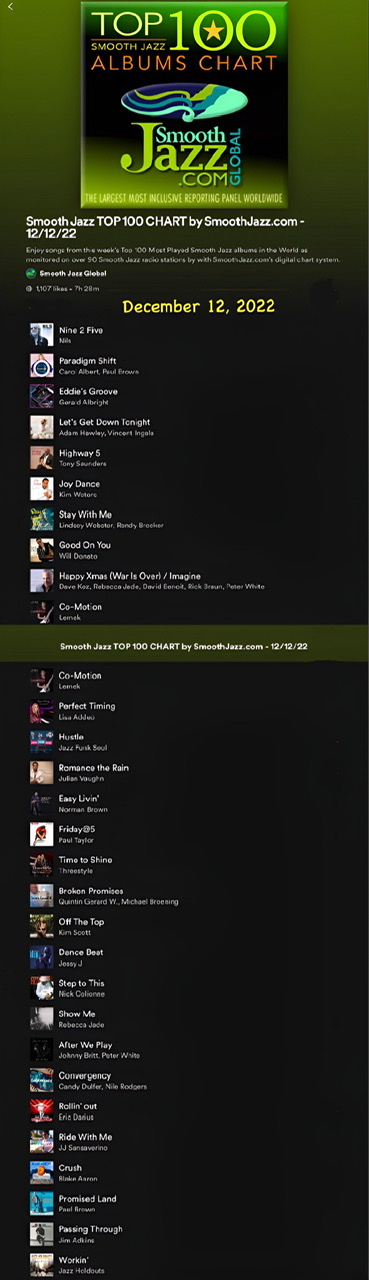

There are still people listening to, purchasing, and attending events featuring jazz. The proof of purchasing and listening to jazz is reflected in Billboard  and others who chart jazz songs or albums that the public is paying for and listening to the most. You can see several of these clickable charts below.

and others who chart jazz songs or albums that the public is paying for and listening to the most. You can see several of these clickable charts below.

Response to (Winbush 0) on jazz's status in history books[edit]

(Winbush 0) claims that jazz may end up only having a few lines in history books. We already know this is false because there are currently numerous history books with many pages, chapters, and entire books on the subject of jazz.

- EVIDENCE: Current status of jazz in history books.

Jazz has already had and will continue to significantly impact the music scene.

- EVIDENCE: The proliferation of jazz sub-genres in and of itself has had a significant impact, however interpreted, on music and musical history.

Numerous non-jazz genres have started incorporating jazz into their music.

- EVIDENCE FOR CONTINUATION:

-

Watch David Bennett's "Rock and pop songs inspired by jazz"

Watch David Bennett's "Rock and pop songs inspired by jazz"

-

-

Watch Aimee Nolte's "Rock and pop songs that use a lot of jazz"

Watch Aimee Nolte's "Rock and pop songs that use a lot of jazz"

-

-

ChatGPT3 (version January 9) Accessed January 25, 2023 gives this answer to how jazz has influenced contemporary music.

ChatGPT3 (version January 9) Accessed January 25, 2023 gives this answer to how jazz has influenced contemporary music.

-

“Here are a few specific examples of how jazz has influenced contemporary non-jazz music:

- Jazz harmony and chord progressions have been used extensively in pop music. For example, many contemporary R&B and neo-soul artists incorporate jazz chords and progressions into their music, such as D'Angelo and Erykah Badu.

- Jazz rhythms, particularly the syncopated rhythms of swing and bebop, have been used in hip-hop and electronic music. Artists like J Dilla and Madlib have incorporated jazz rhythms into their beats and sample jazz recordings extensively in their music.

- Jazz improvisation and experimentation has been an influence on rock music. Bands like The Mars Volta and Snarky Puppy have incorporated jazz elements such as complex time signatures and extended improvisation into their music.

- Jazz musicians and their approach to improvisation and experimentation has also been an influence on contemporary electronic and experimental music like Flying Lotus, Thundercat, and Kamasi Washington.

- Jazz fusion, which combines jazz with elements of rock, funk, and other genres, has been a popular subgenre and continues to influence contemporary music, especially in instrumental and experimental music scenes.”[14] (bold not in original)

Music schools have jazz programs.

- EVIDENCE FOR JAZZ MUSIC SCHOOLS:

-

ChatGPT3 (version January 9) describes jazz education in the United States with representative schools.

ChatGPT3 (version January 9) describes jazz education in the United States with representative schools.

-

“Jazz education in the United States typically takes place at the college and university level, and often includes both performance and academic components. Jazz programs usually offer classes on jazz history, theory, and performance, as well as opportunities for students to perform in ensembles and study with professional jazz musicians.Many colleges and universities have established jazz programs that offer both undergraduate and graduate degrees in jazz performance, composition, and education. These programs often provide students with a strong foundation in jazz history, theory, and improvisation, as well as opportunities for performance and ensemble work. Some programs also offer specialized courses in jazz arranging, composing, or recording.

In addition to college and university programs, there are also numerous summer jazz camps, workshops, and festivals that provide opportunities for jazz education. These programs often bring together students of all ages and skill levels to study with professional jazz musicians and educators.

Overall, jazz education in the United States is diverse and well-established, providing students with a wide range of opportunities to study and perform jazz music, and to learn from experienced jazz musicians and educators.

What are the names of colleges and universities that teach jazz?

There are many colleges and universities in the United States that offer jazz programs. Here are a few well-known examples:

- The Juilliard School in New York City, which is widely considered to be one of the top music schools in the world.

- The Manhattan School of Music in New York City, which offers undergraduate and graduate degrees in jazz performance and composition.

- The New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, which has a renowned jazz program and offers undergraduate and graduate degrees in jazz performance, composition, and education.

- The Berklee College of Music in Boston, which is one of the most renowned music institutions in the world, offers undergraduate and graduate degrees in jazz performance, composition and music production.

- Indiana University in Bloomington, which has a well-respected jazz studies program and offers undergraduate and graduate degrees in jazz performance and education.

- Manhattan College in New York City, which offers a strong jazz program for undergraduate students.

- William Paterson University in Wayne, New Jersey, which has a renowned jazz studies program that offers undergraduate and graduate degrees in jazz performance and education.

- North Texas State University in Denton, Texas, which has a well-established jazz studies program and offers undergraduate and graduate degrees in jazz performance, composition, and education.

These are just a few examples, but there are many other colleges and universities that offer jazz programs in the United States. These institutions are known for their strong jazz education programs and their great resources to support students, many of them have famous jazz musicians and educators as faculty members.”[15] (bold not in original)

-

Berklee Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice focuses on generating equity in the jazz field and establishing jazz's role in the larger struggle for gender justice.

Berklee Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice focuses on generating equity in the jazz field and establishing jazz's role in the larger struggle for gender justice.

-

-

Wikipedia: Jazz education lists 492 current collegiate jazz programs globally.

Wikipedia: Jazz education lists 492 current collegiate jazz programs globally.

-

Response to (Winbush 0) on the current relevance of jazz[edit]

Best jazz of the year[edit]

To provide evidence for jazz's current relevance on the music scene, look at the reviews of the best jazz offered for that year.

-

2022 JazzTimes.com, "Year in Review: The Top 40 Jazz Albums of 2022" (critics pick best new releases of the year), published December 19, 2022.

2022 JazzTimes.com, "Year in Review: The Top 40 Jazz Albums of 2022" (critics pick best new releases of the year), published December 19, 2022.

-

Print or online jazz magazines[edit]

NOTE: Click on a magazine name or image to go to its source.

Jazz magazines in the United States[edit]

-

Wikipedia: List of jazz magazines with twenty-nine listed on January 20, 2023.

Wikipedia: List of jazz magazines with twenty-nine listed on January 20, 2023.

-

-

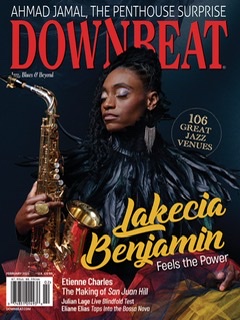

DownBeat

DownBeat

has been continuously published since 1934.

has been continuously published since 1934.

-

-

Read about the history and founding of Downbeat.

Read about the history and founding of Downbeat.

-

-

Jazziz published with a CD 💿 since 1984.

Jazziz published with a CD 💿 since 1984.

-

-

All About Jazz's website and two magazines in Winter & Spring 2004:

All About Jazz's website and two magazines in Winter & Spring 2004:

-

-

Smooth Jazz Magazine Started in March/April 2015 to the present.

Smooth Jazz Magazine Started in March/April 2015 to the present.

-

-

Cadence Read about Cadence magazine.

Cadence Read about Cadence magazine.

-

What are the names of jazz magazines?

"," "," "," "Jazz News," "Jazz Perspective," "Jazz Right Now," "Jazz Society of Oregon," "Jazzwise," "The Jazz Review," "Jazzworld," "Mons Records Jazz Magazine," "Straight Ahead Jazz Magazine," and "The Velvet Note." These are just a few examples and there are many more jazz magazines available.

Name even more jazz magazines.

Here are more jazz magazines: "," "Cadence Magazine," "The Chicago Jazz Magazine," "The Jazz Break," "Jazz Chicago," "Jazz Connect," "Jazz Da Gama," "Jazz Education Journal," "Jazz History Online," "Jazz In Europe," "Jazz In Press," "Jazz Inside New York," "Jazz Life," "Jazz Monthly," "Jazz News Letter," "Jazz Now," "Jazz On Line," "Jazz Times Europe," "Jazz Weekly," "Jazz World," "Jazz'n'More," "JazzReview.com" and "JazzTrail" Please note that this is not an exhaustive list and there are likely many more jazz magazines in existence and some of the names mentioned might not be currently active.

Jazz magazines in print or online from around the world[edit]

-

See Matt Fripp's JazzFuel's list of ten "Great Jazz Magazines (2021)"

See Matt Fripp's JazzFuel's list of ten "Great Jazz Magazines (2021)"

-

Jazz magazines from around the world:

- "Jazz Forum" (Poland)

- "Jazz Podium" (Germany)

- "Jazzwise" (UK)

- "Jazzman" (France)

- "Jazz Thing" (Germany)

- "Jazz 'n' More" (Switzerland)

- "Jazz Hot" (France)

- "Jazz It" (Italy)

- "Jazz Special" (Denmark)

- "Jazzthetik" (Germany)

- "Jazzwise" (UK)

- "Cadence" (USA)

- "Jazz Da Gama" (India)

- "Jazz In Press" (Italy)

- "Jazz In Europe" (Belgium)

- "Jazztrail" (USA)

These are some examples of jazz magazines from around the world, but there may be many more in existence. Please note that this list is not exhaustive and some of the magazines mentioned might not be currently active.

Canadian jazz magazines:

- "Cadence Magazine"

- "The Canadian Jazz Report"

- "Jazz Scene"

- "Jazz Report"

- "Jazz Perspectives"

- "The WholeNote"

- "JazzScene Magazine"

- "JazzCanada"

- "OttawaJazzScene.ca"

- "TorontoJazz.com"

- "VancouverJazz.com"

Please note that this list is not exhaustive and some of the magazines mentioned might not be currently active.

Jazz magazines from Japan:

- "Swing Journal"

- "Jazz Life"

- "Jazz Japan"

- "Jazz Critique"

- "Jazz Japan Times"

- "Jazz Tokyo"

Please note that this list is not exhaustive and there may be other jazz magazines in Japan, and also some of the magazines mentioned might not be currently active.

Jazz magazines from Europe:

- "Jazz Forum" (Poland)

- "Jazz Podium" (Germany)

- "Jazzwise" (UK)

- "Jazzman" (France)

- "Jazz Thing" (Germany)

- "Jazz 'n' More" (Switzerland)

- "Jazz Hot" (France)

- "Jazz It" (Italy)

- "Jazz Special" (Denmark)

- "Jazzthetik" (Germany)

- "Jazz In Press" (Italy)

- "Jazz In Europe" (Belgium)

- "Jazz Podium Spezial" (Germany)

- "Jazzwise" (UK)

- "Jazz'n'More" (Switzerland)

- "Jazz Magazine" (France)

- "Jazz & Tzaz Magazine" (Greece)

- "Jazz Journal" (UK)

Please note that this list is not exhaustive, and there may be many more jazz magazines in Europe, Also, some of the magazines mentioned might not be currently active.

-

Turkish jazz Jazz Dergisi magazine published between January 1996 and June 2016 over twenty-one years with eighty-two issues.

Turkish jazz Jazz Dergisi magazine published between January 1996 and June 2016 over twenty-one years with eighty-two issues.

-

-

OrkesterJournalen now Jazz (Sweden)

OrkesterJournalen now Jazz (Sweden)  is Sweden´s only jazz magazine and the world's oldest publication beginning in 1933.

is Sweden´s only jazz magazine and the world's oldest publication beginning in 1933.

-

-

Slovakia's online jazz magazine Skjazz.sk

Slovakia's online jazz magazine Skjazz.sk  since 2006.

since 2006.

-

-

Switzerland's Jazz Magazine

Switzerland's Jazz Magazine  Jazz‘n‘More.

Jazz‘n‘More.

-

-

Germany's Jazz Podium

Germany's Jazz Podium  published since 1952.

published since 1952.

-

“Jazz Podium is a German-language jazz magazine published eight times a year (double editions: March/April, June/July, August/September, December/January). It was founded in 1952—the first issue was published in Vienna in September 1952—and was published for a long time by Dieter Zimmerle. After his death, Gudrun Endress was the long-time editor-in-chief (and managing director with Frank Zimmerle) from 1989 to 2018 and Stuttgart was the headquarters of the magazine until 2018. Their original title was The International Podium with the current announcements of the German Jazz Federation. Initially, the magazine came out with twenty pages. Today it's about eighty. Since 2021, the magazine has also been published as an e-paper. A digital archive with all past issues since 1952 is under construction and is accessible to subscribers.

In addition to musician portraits and interviews, the magazine contains current jazz news, reviews of CDs, films as well as books and references to planned concert and club appearances or Festival and radio programs in German-speaking countries and in some neighboring countries. The magazine is aimed at musicians as well as interested laymen of all generations.The authors (musicologists, jazz experts, musicians), photographers and editors only write and work for an expense allowance. There are around 100 freelancers. The circulation in 2002 was 12,000 copies, most of which are distributed as a subscription.”[16] (bold not in original)

Active jazz clubs[edit]

- 🎷 There are currently active and thriving jazz clubs and venues around the world and in the United States.

- 🎷 See Matt Fripp's JazzFuel's "List of the best jazz clubs in Italy."

Active jazz festivals[edit]

Jazz Appreciation Month (JAM) and International jazz day[edit]

- 🌎 Jazz Appreciation Month (JAM)

during every April and begun in 2001 by the Smithsonian museum.

during every April and begun in 2001 by the Smithsonian museum.

- 🌎 Jazz Appreciation Month (JAM)

- 🌍 International Jazz Day

on every April 30th.

on every April 30th.

- 🌍 International Jazz Day

Jazz around the world[edit]

- 🌏 Jazz in India Taj Mahal Foxtrot: The Story of Bombay's Jazz Age

- 🌏 Polish Jazz For Dummies: 60 Years Of Jazz From Poland written by Cezary L. Lerski

Response to (Winbush 1) on the current status of jazz[edit]

(Winbush 1): The most popular forms of jazz barely qualify as jazz. PoJ.fm finds these general observations are partially true. The general public is less familiar with classic jazz performances and has more likely only heard 'watered down' jazz. The best-selling smooth jazz artist is soprano saxophonist (primary instrument) Kenny G (b. 1956), who also plays on alto and tenor saxophones and flutes in the additional music categories of Adult Contemporary and Easy Listening.

It is not that the chosen popular kinds of music are not jazz as much as they are softer and more easily accessible to musical ears than the more complex rhythms and complex harmonies found in Bebop, jazz/rock fusion, or free jazz, to name a few. These other jazz styles' frenetic energy and dynamism are less easily mass-marketed.

The top two choices by jazz listeners at the streaming service Jazz24.org were heavy favorites: (1) "Take Five" by the Dave Brubeck Quartet and (2) "So What" by the Miles Davis Quintet. "Take Five" is in 5/4 time, hence presumably explaining the title of the tune, and, at the time, was considered an odd time signature. "So What" is on the best-selling jazz album of all time, "Kind of Blue," so its popularity is well-known.

The rest of the top twenty (out of the one hundred ranked) are all familiar recordings by established jazz musicians, as seen in the list below.

- 3. "Take The A Train" — Duke Ellington

- 4. "Round Midnight" — Thelonious Monk

- 5. "My Favorite Things" — John Coltrane

- 6. "A Love Supreme (Acknowledgment)" — John Coltrane

- 7. "All Blues" — Miles Davis

- 8. "Birdland" — Weather Report

- 9. "The Girl From Ipanema" — Stan Getz & Astrud Gilberto

- 10. "Sing, Sing, Sing" — Benny Goodman

- 11. "Strange Fruit" — Billie Holiday

- 12. "A Night in Tunisia" — Dizzy Gillespie

- 13. "Giant Steps" — John Coltrane

- 14. "Blue Rondo a la Turk" — Dave Brubeck

- 15. "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat" — Charles Mingus

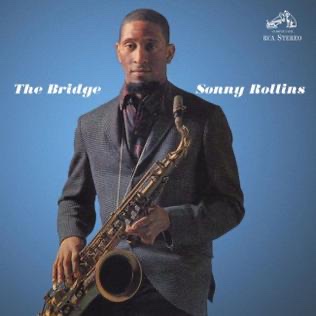

- 16. "Stolen Moments" — Oliver Nelson

- 17. "West End Blues" — Louis Armstrong

- 18. "God Bless The Child" — Billie Holiday

- 19. "Cantaloupe Island" — Herbie Hancock

- 20. "My Funny Valentine" — Chet Baker

Still, in the top one-hundred favorite recorded jazz performances by song at Jazz24.org, voted on by jazz listeners out of a choice of fifteen hundred, few would disagree with the excellence of the chosen songs. Nevertheless, there is still the factor of smoother and cooler jazz songs ranking higher than any song by, say, a player of European free jazz, avant-garde jazz, and free improvisation such as Peter Brötzmann (b. 1941).

Notice number 11. on the above list, Billie Holiday's 1939 recording of a song about lynching, "Strange Fruit." Wikipedia: Strange Fruit categorizes the genres of the song to be blues and jazz.[17] At a minimum, the jazz component of the recording begins with pianist Sonny White improvising an introduction before Holiday starts singing after seventy seconds.

When Winbush supports his points, he has complaints against Lady Gaga and Annie Lennox qualifying as jazz singers when they started in non-jazz genres. To remind the reader, here is how Winbush characterizes the three singers.

“This week's Billboard contemporary jazz charts has Tony Bennett's collaboration with Lady Gaga is #2, and Annie Lennox follows at #3. If you want to call Bennett a jazz singer, I won't kick, but Gaga and Lennox? Pop stars slumming gets a definite "No."

Would anyone claim that Tony Bennett (b. 1926) is not a jazz singer? Everybody agrees that Tony Bennett is one of the best American singers of all time.

“Bennett has amassed numerous accolades throughout his career, including twenty Grammy Awards (including a Lifetime Achievement Award presented in 2001) and two Primetime Emmy Awards. He was named an NEA Jazz Master and a Kennedy Center Honoree. Bennett has sold over fifty million records worldwide.”[18] (bold not in original)

There is no such thing as a jazz song; there are only ways to sing a song in a jazz manner. Vocalists can sing a jazz standard in a non-jazz way. Hence, it is not the song itself that makes the performance be jazz; instead, it is how a singer performs the music that makes it jazz. Any singer, from any musical style could sing a song in a jazz manner if sung jazzily. Therefore, both Lady Gaga and Annie Lennox could be singing their songs in a jazz style even if they sang pop and rock songs in the past.

“"Nostalgia" debuted at number nine on the UK Albums Chart, becoming Lennox's sixth UK top-10 solo album. It has since been certified Gold by the BPI for sales in excess of 100,000 copies in the UK. It debuted at number 10 on the US Billboard 200 with first-week sales of 32,000 copies, earning Lennox her third top-10 solo album on the chart, as well as her first-ever number-one album on both Billboard's Jazz Albums and Traditional Jazz Albums charts. It had sold 139,000 copies in the United States as of April 2015. "Nostalgia" peaked inside the top ten in Austria, Canada, Italy and Switzerland. The album was nominated for Best Traditional Pop Vocal Album at the 57th Grammy Awards.”[19] (bold not in original)

Is jazz-inspired vocal pop music a bad thing for jazz? Doesn't Winbush advocate in (Winbush 6) that jazz should strive to achieve more mass appeal? He can't have it both ways that watered-down jazz is not jazz while advocating for broadening jazz's appeal to the music-listening population.

Winbush is more or less correct that the Billboard Contemporary jazz chart is a lot of the time 'jazz-lite' because what's bought by listeners because of its popular appeal is not what defines the best jazz music as judged by knowledgeable jazz musicians, jazz critics, and theorists.

What's wrong with contemporary smooth jazz?[edit]

Smooth jazz pushed itself onto the Billboard recording charts in 1987, not as a whim but due to the sales of this style of playing music.

Smooth jazz has jazz components but lacks the unencumbered 'spirit' of jazz where musicians can branch out from the consistent smoothness found in most recordings labeled as smooth jazz. Smooth jazz is always glossy and polished sounding because of stylistic restrictions that always have a soothing musical background effect on listeners. Things don't 'stand out' on a smooth jazz recording. It is all of one harmonious development. Shrillness and discordance are forbidden stylistically, or producers fear losing their listeners. Such a point of view is generally true since the more straight-ahead, or what Billboard and others categorize as 'traditional' jazz, a term that in the past implied New Orleans Dixieland, has fewer sales because listeners buy it less than smooth jazz styles.

Of course, there may be some musical exceptions when lumping a large number of musical performances under an umbrella category and expecting perfect uniformity among all candidates. Still, smooth jazz practioners conform to a high degree to a particular musical model.

There are different styles that one might use to describe a musical style. These stylistic critiques range from friendly and supportive to hostile and negative even when allegedly describing the same phenomenon. For a quick example, in describing what smooth jazz sounds like are descriptions in contrasting styles called friendly, unfriendly, and neutral.

- FRIENDLY: As a style of music, smooth jazz gives listeners the impression of an infinitely long pleasing and harmonious sonic pillow that drifts them into a luxurious state of musical happiness.

- UNFRIENDLY: As a style of music, smooth jazz presents a water downed jazz-lite smeared with easy-listening pop music and lightweight R&B.

- NEUTRAL: “Smooth Jazz is an outgrowth of fusion, one that emphasizes its polished side. Generally, smooth jazz relies on rhythms and grooves instead of improvisation. There are layers of synthesizers, lite-funk rhythms, lite-funk bass, elastic guitars, and either trumpets, alto, or soprano saxophones. The music isn't cerebral, like hard bop, nor is it gritty and funky like soul-jazz or groove—it is unobtrusive, slick, and highly polished, where the overall sound matters more than the individual parts.”[20] (bold and bold italic not in original)

Why jazz lovers dislike smooth jazz[edit]

At Quora.com, music book author, Todd Lowry gives at least seven reasons why smooth jazz has limited appeal to jazz music aficionados. Numbers added by PoJ.fm.

“Smooth jazz is NOT jazz.

(1) There is no jazz improvisation. Jazz is about improvisation, living in the moment, revelation.

(2) Smooth jazz harmonies are rarely complex like real jazz harmonies.

(3) Smooth jazz virtually never swings like real jazz.

(4) There is little blues influence in smooth jazz like there is in real jazz.

(5) Jazz has an African heritage and a storied history that goes from Ragtime to Dixieland to Stride Piano to Boogie-Woogie to Swing to Bop to Cool to Hard Bop to Free Form to Fusion to Latin, etc.

(6) There is no historical perspective in smooth jazz nor (7) use of the jazz standard repertoire.”[21] (bold not in original)

Also, generally speaking, smooth jazz all sounds alike.

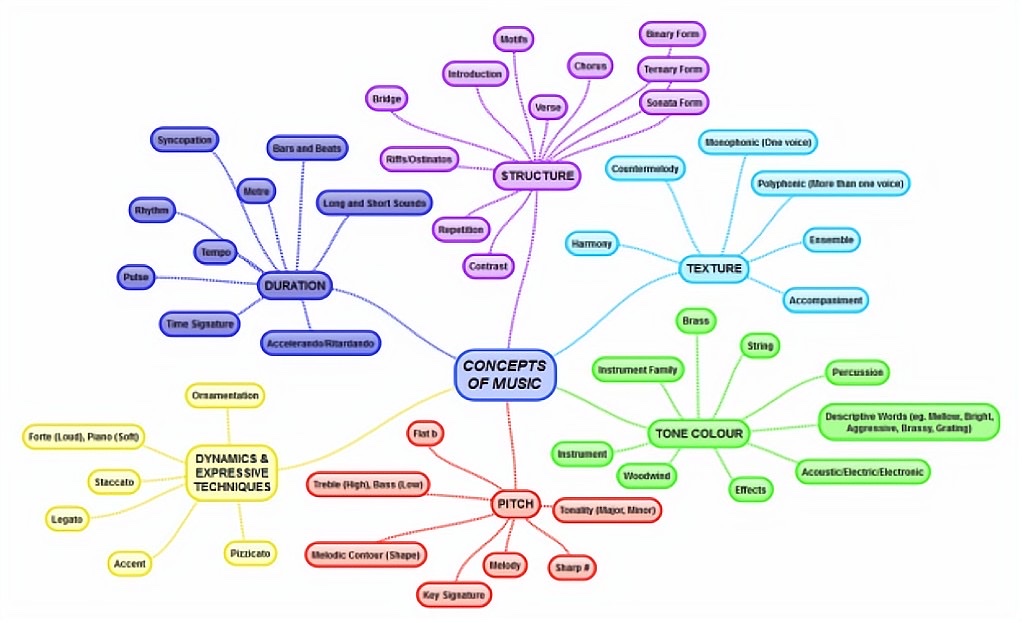

Response to (Winbush 2) on the fragmentation of jazz[edit]

(Winbush 2): Jazz is highly fragmented. Contemporary straight-ahead jazz fans into a Wynton Marsalis don't have much use for avant-garde, experimental types like a Cecil Taylor or John Zorn and both loathe "smooth" jazz as practiced by a Kenny G. or Dave Koz. The problem is jazz is such a tiny portion of overall music sales (down to under 2 percent in 2014), there's really no place for elitism and exclusion. There simply isn't enough slices of the pie for anyone to be thumbing their noses at the subdivisons of jazz.

Jazz has many sub-genres; many jazz listeners dislike some of them and don't actively listen to others.

Think of it this way. Does everybody like ballet? No. Is ballet likely one of the greatest forms of dance by human beings? Yes. The two male ballet stars of Rudolph Nureyev (1938–1993) and Mikhail Baryshnikov (b. 1948) were phenomenal athletes. Barishnikoff would often appear to defy gravity in his athleticism. But ballet is more of an acquired taste than some other forms of entertainment like American 🇺🇸 football 🏈 or world-wide 🗺 soccer ⚽️.

Jazz is more like ballet and pop music is more like American football 🏈 or soccer ⚽️. Therefore, jazz is an acquired taste needing nurturing and exposure to listeners so they can be more educated about the music. This means it is unlikely ever again to have the popular domination it had in the 1930s and 40s.

Consequently, each jazz sub-genre is striving for market share. This might partially explain the snipping against other jazz sub-genres to which Winbush refers. So. it turns out, there is a place for 'elitism and exclusion' since each sub-genre is working to get their very thin slice of the pie.

Response to (Winbush 3) on hearing jazz[edit]

(Winbush 3): The collapse of the record labels and radio stations still playing jazz as a format have sped the decline of the genre's popularity. If you can't hear it on the radio, you're probably not going to find out about new and older artists still making music and clubs aren't going to book jazz artists and you're not going to able to find venues to hear live jazz. As far as TV goes, fuhgeddabouit. My, what a tangled web we weave.

-

A great bulk of music listening since at least 2010 has switched to streaming services for their efficiency, convenience, depth of playlists and recordings so one can much more easily listen to streaming jazz than ever before with thirty-two active music streaming providers listed at Wikipedia. Access to jazz recordings has perhaps never been higher.

A great bulk of music listening since at least 2010 has switched to streaming services for their efficiency, convenience, depth of playlists and recordings so one can much more easily listen to streaming jazz than ever before with thirty-two active music streaming providers listed at Wikipedia. Access to jazz recordings has perhaps never been higher.

-

-

There are plenty of places to see jazz performed at jazz festivals around the world. See active jazz festivals.

There are plenty of places to see jazz performed at jazz festivals around the world. See active jazz festivals.

-

-

There are still clubs booking jazz musicians. See "Fifty Best Jazz Clubs in America.

There are still clubs booking jazz musicians. See "Fifty Best Jazz Clubs in America.

-

-

There are still at least sixty-seven jazz radio stations. Wikipedia: List of jazz radio stations lists eighty-five stations playing jazz in the United States.

There are still at least sixty-seven jazz radio stations. Wikipedia: List of jazz radio stations lists eighty-five stations playing jazz in the United States.

-

-

Jazz is still occasionally heard on television. Read Liam Maloy's "Ain't Misbehavin': Jazz music in children’s television," Jazz Research Journal, September 20, 2019.

Jazz is still occasionally heard on television. Read Liam Maloy's "Ain't Misbehavin': Jazz music in children’s television," Jazz Research Journal, September 20, 2019.

-

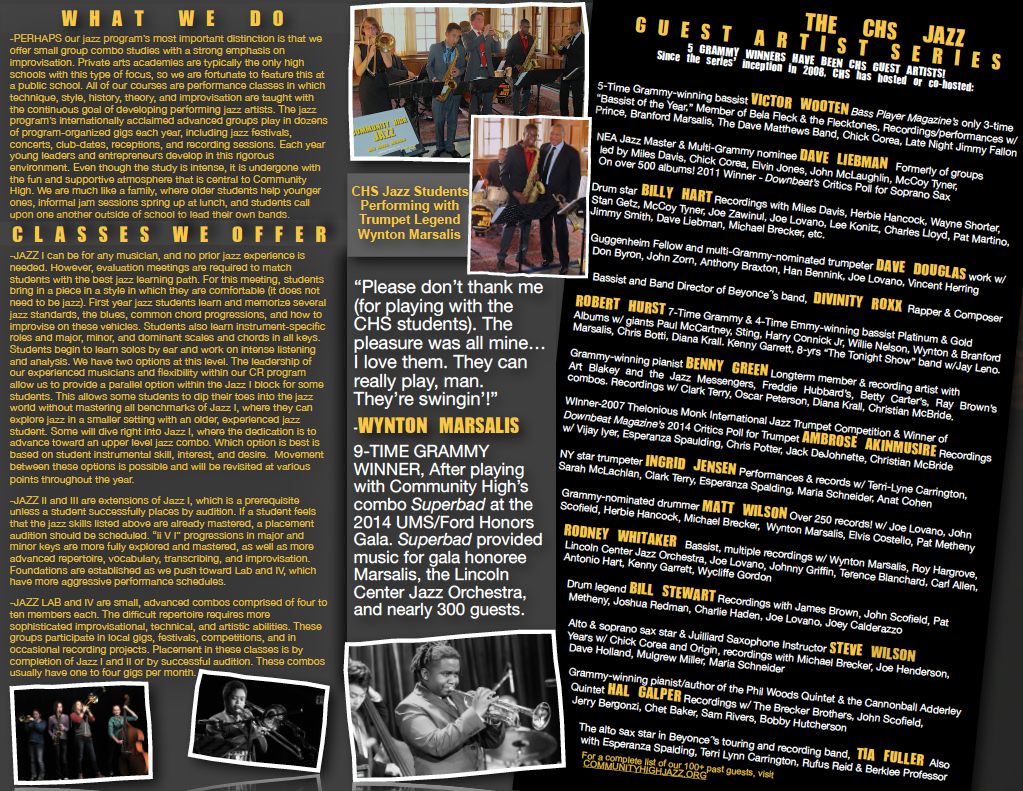

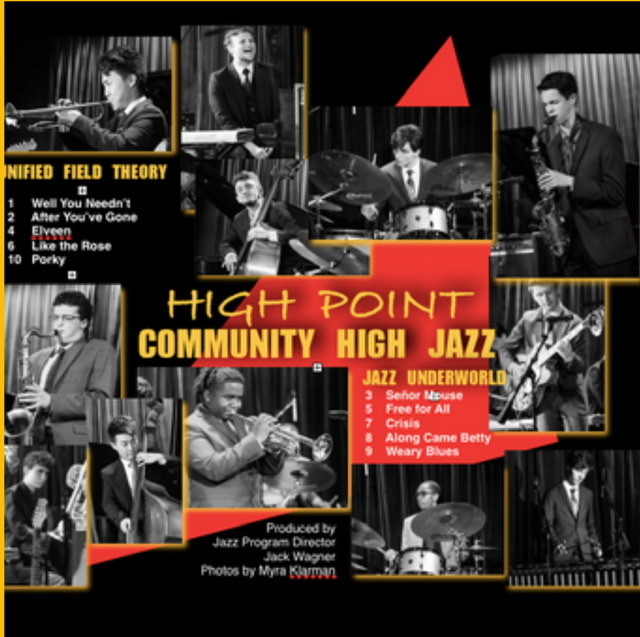

Response to (Winbush 4) on the state of jazz education[edit]

(Winbush 4): Schools are chopping their music classes and there goes a feeder system for kids who aspire to play something more complex than turntables and ProTools. If you can't hear jazz, see jazz or play jazz, where's the next generation of new blood coming from to replace the old blood?

-

See the Herbie Hancock Institutes's thorough outline of "Jazz Education" in the United States. The Hancock Institute points out that jazz since the 1960s has continually increased its credibility until jazz has now become “legitimized” in formal academia because university jazz studies programs proliferated in the 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s. Today's jazz students study and practice with their classical music counterparts in America’s most prestigious schools of music and conservatories, including Eastman, Indiana University, Juilliard, or the New England Conservatory, to name a few. Students can now earn a bachelors, masters, or doctoral degree in jazz studies with more than one hundred twenty bona fide jazz programs. Around the world, post secondary jazz degree programs are now well-established.

See the Herbie Hancock Institutes's thorough outline of "Jazz Education" in the United States. The Hancock Institute points out that jazz since the 1960s has continually increased its credibility until jazz has now become “legitimized” in formal academia because university jazz studies programs proliferated in the 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s. Today's jazz students study and practice with their classical music counterparts in America’s most prestigious schools of music and conservatories, including Eastman, Indiana University, Juilliard, or the New England Conservatory, to name a few. Students can now earn a bachelors, masters, or doctoral degree in jazz studies with more than one hundred twenty bona fide jazz programs. Around the world, post secondary jazz degree programs are now well-established.

-

-

See JazzFuel.com's "Ten of the Best Music Schools for Jazz in the United States," March 19, 2022.

See JazzFuel.com's "Ten of the Best Music Schools for Jazz in the United States," March 19, 2022.

-

-

Best Schools to Study Jazz in the United States and get a degree in Jazz Studies, Performance, or Jazz Composition, according to CareersInMusic.com. The top fifteen colleges, universities, and conservatories to study jazz are listed below in alphabetical order. For a brief description of each school's jazz program, click here.

Best Schools to Study Jazz in the United States and get a degree in Jazz Studies, Performance, or Jazz Composition, according to CareersInMusic.com. The top fifteen colleges, universities, and conservatories to study jazz are listed below in alphabetical order. For a brief description of each school's jazz program, click here.

-

- 1. Berklee College of Music

- 2. Columbia University

- 3. Eastman School of Music

- 4. Indiana University Jacobs School of Music

- 5. John Hopkins Peabody Institute

- 6. Juilliard School

- 7. Manhattan School of Music

- 8. New England Conservatory of Music

- 9. New School for Jazz and Contemporary Music

- 10. Northwestern University Bienen School of Music

- 11. Oberlin Conservatory

- 12. University of Miami Frost School of Music

- 13. University of North Texas College of Music

- 14. University of Southern California Thornton School of Music

- 15. Western Michigan University School of Music

-

Ph.D. in Jazz & Improvisation

Ph.D. in Jazz & Improvisation

- ♦ Melbourne Conservatorium of Music

- ♦ Effortless Mastery Institute at

with Director Kenny Werner (b. 1951) who wrote Effortless Mastery (1996).

with Director Kenny Werner (b. 1951) who wrote Effortless Mastery (1996).

-

-

For jazz education programs internationally see the thirty-one listings at the bottom of the 2019 Downbeat's Student Music Guide: Where to Study Jazz.

For jazz education programs internationally see the thirty-one listings at the bottom of the 2019 Downbeat's Student Music Guide: Where to Study Jazz.

-

-

The Jazz Education Network (JEN) was an outgrowth of the International Association of Jazz Education (IAJE) (founded in 1968 and bankrupted and defunct since 2008) with the Jazz Education Network (JEN) beginning then in 2008 with a mission dedicated to building the jazz arts community by advancing education, promoting performance, and developing new audiences for the music.

The Jazz Education Network (JEN) was an outgrowth of the International Association of Jazz Education (IAJE) (founded in 1968 and bankrupted and defunct since 2008) with the Jazz Education Network (JEN) beginning then in 2008 with a mission dedicated to building the jazz arts community by advancing education, promoting performance, and developing new audiences for the music.

-

-

Read the JazzEd magazine, a major publication of the Jazz Education Network (JEN) currently published ten times per year.

Read the JazzEd magazine, a major publication of the Jazz Education Network (JEN) currently published ten times per year.

-

-

Monterey Jazz Festival Education: “As a nonprofit, Monterey Jazz Festival is devoted to education by presenting year-round local, regional, national, and international programs. Thousands of students have been the benefactors of the Festival’s educational efforts through the Jazz in the Schools Program, Summer Jazz Camp, Next Generation Jazz Festival, Next Generation Jazz Orchestra, Next Generation Women in Jazz Combo and Monterey County All-Star Ensembles, which embark on annual performance trips each summer.”

Monterey Jazz Festival Education: “As a nonprofit, Monterey Jazz Festival is devoted to education by presenting year-round local, regional, national, and international programs. Thousands of students have been the benefactors of the Festival’s educational efforts through the Jazz in the Schools Program, Summer Jazz Camp, Next Generation Jazz Festival, Next Generation Jazz Orchestra, Next Generation Women in Jazz Combo and Monterey County All-Star Ensembles, which embark on annual performance trips each summer.”

-

-

(Winbush4) worries about "where's the next generation of new blood" coming from. The answer may be from women and non-binary musicians! Watch the video conference of "Gender and Inclusion in Jazz Education" presented by Australians Ellie Lamb and Darcie Foley at the Association for Music Educators conference on October 28, 2021. The video provides insight into systemic underrepresentation of female and gender diverse students in secondary jazz ensembles and suggests strategies for improving the inclusion and experiences of such students within music programs.

(Winbush4) worries about "where's the next generation of new blood" coming from. The answer may be from women and non-binary musicians! Watch the video conference of "Gender and Inclusion in Jazz Education" presented by Australians Ellie Lamb and Darcie Foley at the Association for Music Educators conference on October 28, 2021. The video provides insight into systemic underrepresentation of female and gender diverse students in secondary jazz ensembles and suggests strategies for improving the inclusion and experiences of such students within music programs.

-

-

Read Christian Wissmuller's interview with drummer and jazz educator at Berklee College of Music Terri Lynne Carrington, "‘We’re Trying to Shift that Narrative’: Terri Lyne Carrington Isn’t Waiting Around for Jazz to Reach its Full Potential," JazzEd magazine, January/February 2022.

Read Christian Wissmuller's interview with drummer and jazz educator at Berklee College of Music Terri Lynne Carrington, "‘We’re Trying to Shift that Narrative’: Terri Lyne Carrington Isn’t Waiting Around for Jazz to Reach its Full Potential," JazzEd magazine, January/February 2022.

-

Response to (Winbush 5) on America's ignorance of jazz[edit]

(Winbush 5): America is ignorant of its jazz history and heritage which is why so many musicians spend their summers touring Europe and Japan. If you're not playing across the pond, you had better find a side gig as a session musician or educator to pay the bills.

🇺🇸 Americans have been learning more about jazz through being exposed to it in secondary school.

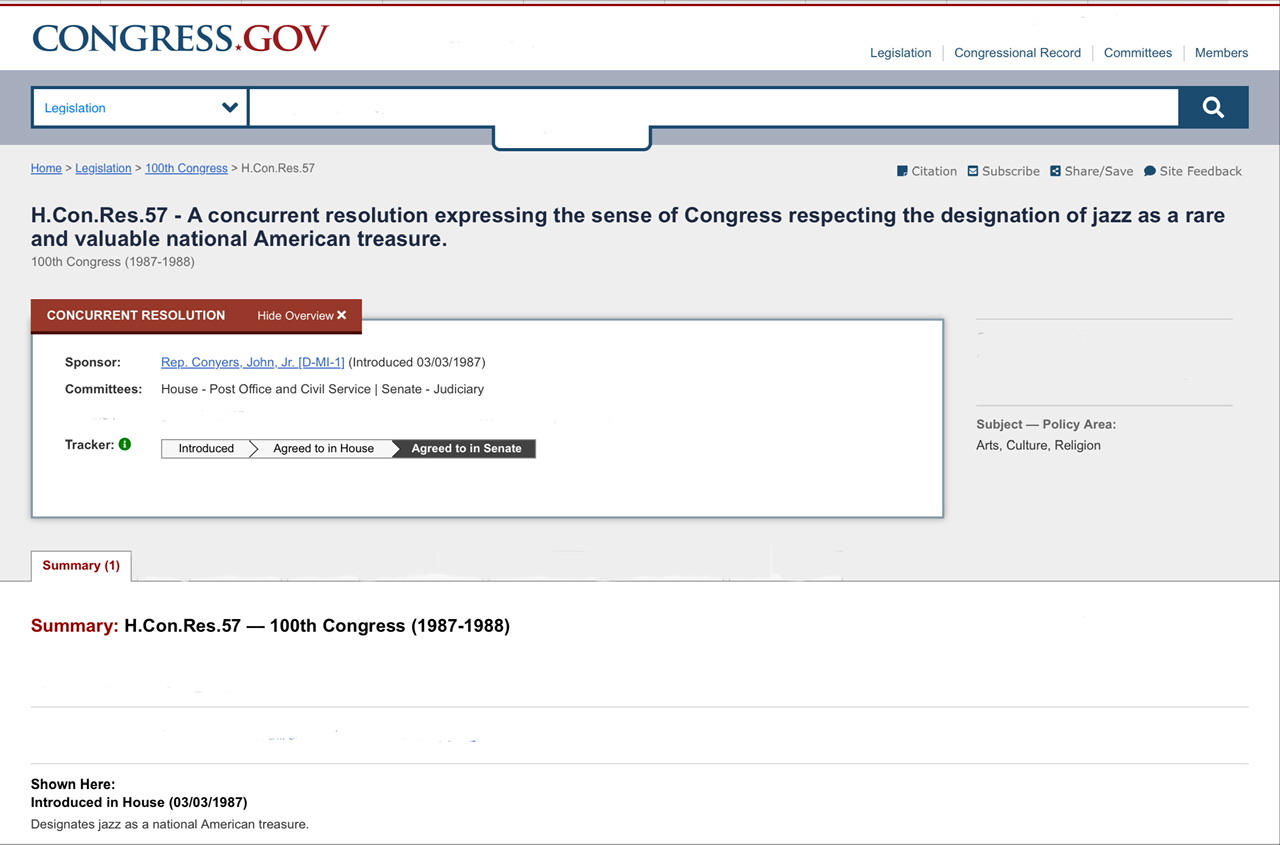

🇺🇸 The 100th U.S. Congress in 1987 passed resolution H.Con.Res.57 introduced by John Conyers (1929–2019) “expressing the sense of Congress respecting the designation of jazz as a rare and valuable national treasure.”

NOTE: Click on image or text of resolution for the source.

Response to (Winbush 6) on jazz being a snob musical genre[edit]

(Winbush 6): Jazz has made itself a genre for snobs, hipsters and pseudo-intellectuals. It needs to find a way to attract the masses.”

It is unlikely that jazz could ever again attract the majority of music listeners. However, much jazz is a learning experience for people because it can be challenging and complex music.

Jazz blogger, Marc Myers, strongly believes that jazz cannot yield from a high art to a mass market appeal without condemning itself to oblivion.

“The bigger question I suppose, is this: Why after all these years content to be high art does jazz continue its silly pursuit of mass-market approval? The fact is, for jazz to survive, it must remain high art. Once it dumbs down and rushes after the mass market, it will truly become road kill. There simply are too many other forms of disposable music out there that are far better at cashing in on tastes and trends.”[22] (bold and bold italic not in original)

Marc Myers continues his analysis of jazz's decline starting in the 1950s and 60s in the United States because jazz musicians wished to promote jazz as high art and not merely for dancing and entertainment.

“Jazz's popularity waned in the 1960s because in the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s, jazz made a conscious decision to be high art, and not all musicians were gifted or financially able to make the sacrifices imposed on serious artists. There's nothing jazz or jazz musicians or record company executives could have done to stop the shifting sands. The fact that jazz has survived as long as it has remains something of a miracle. We can thank the hundreds of artists who remained true to jazz's origins and traditions over the years despite the commercial hardships. Good taste may not pay well but it lasts longer than faddish Faustian bargains.”[23] (bold and bold italic not in original)

Myers conclusion is this:

“Ultimately, jazz is for listening, not dancing.”[24] (bold not in original)

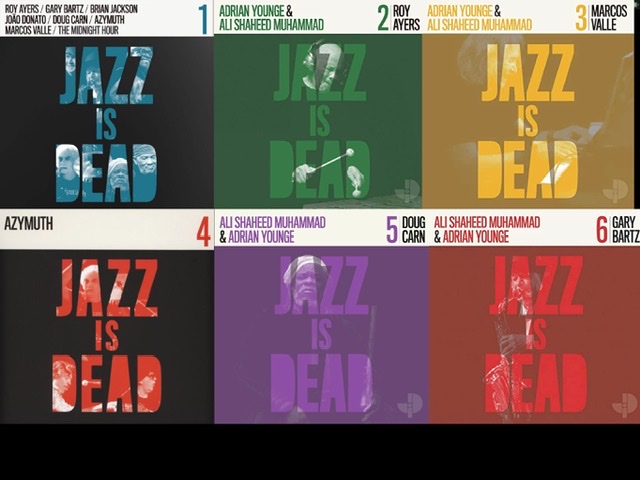

Musician's reveal interest in topic of jazz's death[edit]

For some evidence that people concern themselves with jazz's death, consider the following song titles, albums titles, and even record company titles as represented in the composites below. The sheer number of these proves that musicians find whether or not jazz is dead intriguing and perhaps a challenging issue.

- 🔆 For example, there is a record company that calls itself JAZZ IS DEAD. Click on the picture to go to their website and hear music samples.

- 🔆 Then, there are the 'pure' deniers.

- 🔆 These are followed by those who question whether jazz is dead.

- 🔆 Finally, there are those who deny that jazz is dead!

- 🔆 As an aside, one can also find song titles, artist's names, and album titles claiming their 'subject' is dead for everything from art to rock to discourse.

“So, Is Jazz Really Dead This Time?

The lack of interest in [Ken] Burns's program added fuel to the "Is jazz dead?" debate that had once again become a hot topic with writers, critics, and musicians. In his book Blue: The Murder of Jazz (1997) [p. 220], Eric Nisenson lays the blame for jazz's presumed demise on the neocon philosophy of stressing technique over creativity with statements such as, "Jazz without innovation is a dead art form." Gene Lees also holds Wynton Marsalis and company responsible, but for a different reason. "Either jazz has evolved into a major art form," he writes in Cats of Any Color (1995) [p. 246], "or it is a small, shriveled, crippled art useful only for the expression of the angers and resentments of an American minority. If the former is true, it is the greatest artistic gift of blacks to America, and America's greatest artistic gift to the world. If the latter is true, it isn't dying. It's already dead. Jazz critic Francis Davis also indirectly points his finger at Marsalis, but for still another reason. "'In jazz, the Negro is the product,' Ornette Coleman once sagely observed," he writes in Bebop and Nothingness: Jazz and Pop at the End of the Century (1996) [p. xi]. "But not anymore, or not exactly. The new 'product' in jazz is youth." Davis notes how jazz bands playing in New York clubs began to get younger and sound more traditional (as in "hard boppish") and less experimental after articles ran in The New York Times and Time magazine in 1990 reporting on the "jazz rebirth" and profiled a number of young lions recently signed to record contracts.[25] (bold and bold italic not in original)

If there are young lions playing jazz in the 1990's, then jazz's death has been announced prematurely at that time.

Evaluating why jazz is dead could be true[edit]

Why might trumpeter Nicholas Payton (b. 1973) believe that “Jazz died in 1959” in his artistic poem-like structured essay "On Why Jazz Isn't Cool Anymore," (November 27, 2011)?

Payton may believe jazz died in 1959 because he finds the jazz label too restrictive and overly confining to his artistic aspirations. It potentially limits him from performing other non-jazz genres, he might feel. He wants to take advantage of the new and hip now, not 60 years ago. Do not limit his creativity to only an old genre. Take advantage of all of the new studio technologies and make music in the now and not in some stuffy older styles.

Reasons jazz died in 1959[edit]

As a practicing musician trying to make a living and making money through recordings and live performances, one does not need to limit themselves only to one way or style of making music. There are no requirements of allegiance to only one style or genre for musicians. They can explore and present whatever music captures their imaginations and attention. There is no demand that (jazz) musicians must always play or record music in a jazz vein.

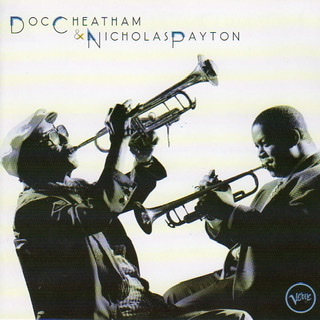

Payton played jazz when he first recorded with Doc Cheatham in 1997,  yet this need not restrict Payton's future musical prospects and genre interests.

yet this need not restrict Payton's future musical prospects and genre interests.

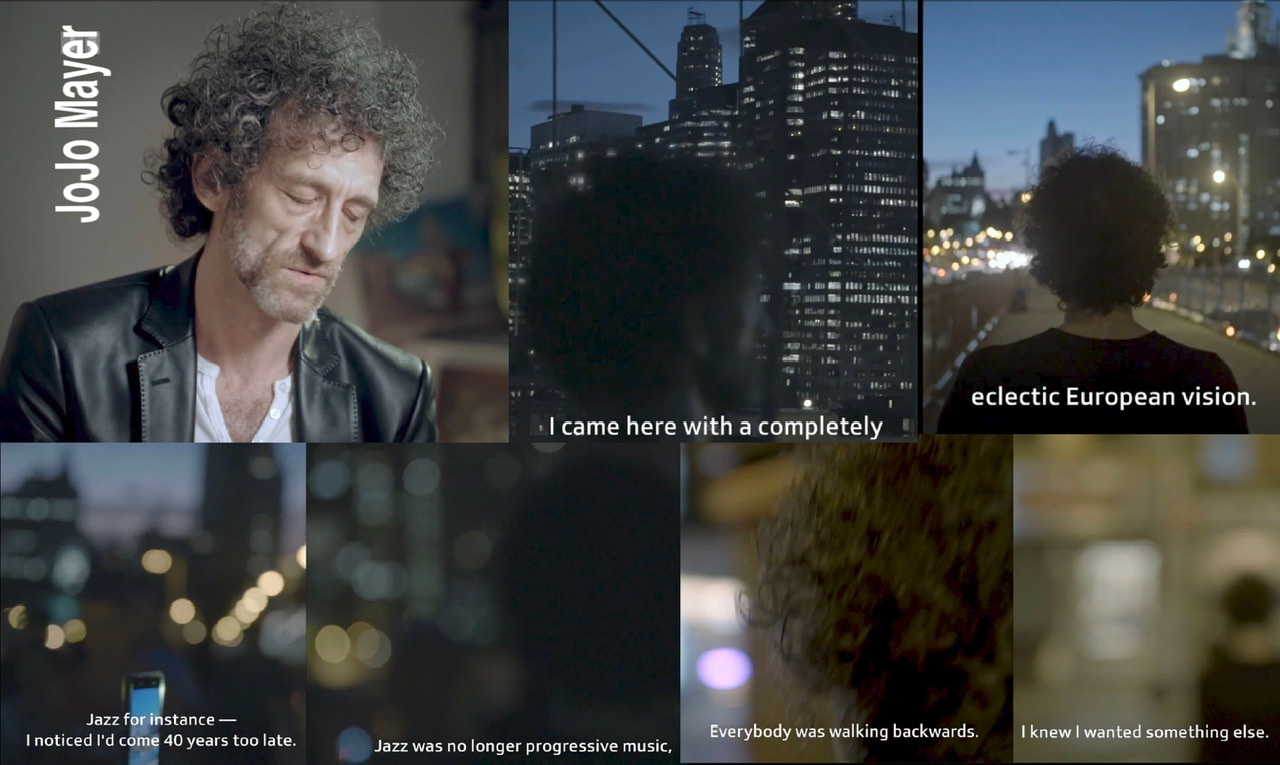

Another musician who found jazz, in effect dead, and "walking backward" (although he does not use the word "dead") is Swiss jazz drummer JoJo Mayer (b. 1963) in the documentary video, "JoJo Mayer — Changing Time (Documentary)." In 2014, Modern Drummer Magazine voted Mayer one of the "50 Greatest Drummers of All Time." When he first came to New York City in the early 1990s, he felt that jazz had stopped forty years before that and had ceased being progressive music and had started, as he put it, "walking backward." Here are some screen captures from the documentary recording Mayer's frustrations with pursuing jazz that he says had become "a conservative music."

Reasons jazz did NOT die in 1959[edit]

NOTE: Click on the page to go to its source. These two album compilations represent great jazz albums released between 1959 and 1979. At least one album, Louis Armstrong's Hot 5 and 7, was recorded much earlier between 1925 and 1928.

If jazz died in 1959, there could be no jazz made after that date because it wouldn't be alive. Because of the fantastic amount of quality music made just in the 1960s alone, under any knowledgeable assessment, for a certainty, these potential judges will accept that at least some of the albums above and below on the following lists qualify as jazz. Therefore, jazz did not die in 1959, as espoused by Payton.

![]() List of post-1950–1996 jazz standards

If there are jazz standards, then musicians are still performing jazz from the 1950s through the 1990s.

List of post-1950–1996 jazz standards

If there are jazz standards, then musicians are still performing jazz from the 1950s through the 1990s.

NOTE: The following examples of great jazz from the 1960s onward does not pretend to be a complete listing. Rather, the lists represent important moments in the history of jazz beginning by highlighting some of the 1960's music of Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, or some music from the jazz superstars of the 1960s.

Great Jazz from America in the 1960s[edit]

-

Free jazz and modal jazz are pushing Bebop forms aside beginning in 1960.

Free jazz and modal jazz are pushing Bebop forms aside beginning in 1960.

-

Miles Davis (1926–1991)[edit]

-

Miles Davis records "Sketches of Spain"

Miles Davis records "Sketches of Spain"  (1960) with the help of Gil Evans.

(1960) with the help of Gil Evans.

-

Miles Davis does "Quiet Nights"

Miles Davis does "Quiet Nights"  (1962) with Gil Evans and a large band. Music writer Scott Yanow describes this Evans/Davis collaboration as “their weakest project.” Miles will not record another big band album until "Aura" in 1989.

(1962) with Gil Evans and a large band. Music writer Scott Yanow describes this Evans/Davis collaboration as “their weakest project.” Miles will not record another big band album until "Aura" in 1989.

-

Davis records "E.S.P."

Davis records "E.S.P."  (Columbia) (1965) with his classic '60s quintet: saxophonist Wayne Shorter, pianist Herbie Hancock, bassist Ron Carter, and drummer Tony Williams. The Ranting Recluse reports on how well this album works: “The first release from what would become known as Davis' "second great quintet" features some of his fieriest acoustic work, as his newly assembled group of young players seem to push him to the limits of Hard Bop and towards a freer, more improvisational side than he'd ever really shown up to this point. The music is complex, with Davis' trumpet and Shorter's sax often seeming to be working at a much higher level of intensity than Hancock's elegant chords and the rhythm section's confident, silky grooves, but the contrast works, providing an excellent platform for freer solos within the context of still recognizable melodic themes and song structures.”

(Columbia) (1965) with his classic '60s quintet: saxophonist Wayne Shorter, pianist Herbie Hancock, bassist Ron Carter, and drummer Tony Williams. The Ranting Recluse reports on how well this album works: “The first release from what would become known as Davis' "second great quintet" features some of his fieriest acoustic work, as his newly assembled group of young players seem to push him to the limits of Hard Bop and towards a freer, more improvisational side than he'd ever really shown up to this point. The music is complex, with Davis' trumpet and Shorter's sax often seeming to be working at a much higher level of intensity than Hancock's elegant chords and the rhythm section's confident, silky grooves, but the contrast works, providing an excellent platform for freer solos within the context of still recognizable melodic themes and song structures.”

-

Miles Davis records "Filles de Kilimanjaro"

Miles Davis records "Filles de Kilimanjaro"  (Columbia) (1968) with Wayne Shorter (ts), Herbie Hancock (electric Rhodes piano), Chick Corea (kyb), Ron Carter (b), Dave Holland (b), and Tony Williams (d).

(Columbia) (1968) with Wayne Shorter (ts), Herbie Hancock (electric Rhodes piano), Chick Corea (kyb), Ron Carter (b), Dave Holland (b), and Tony Williams (d).

- Miles Davis - "Bitches Brew" (Columbia) [Rec. 1969] Miles Davis (t), Wayne Shorter (ss), Bennie Maupin (b cl), Joe Zawinul, Chick Corea (el p), John McLaughlin (g), Dave Holland (b), Harvey Brooks (el b), Lenny White, Jack DeJohnette (d), Don Alias (perc), and Jumma Santos (shaker). The album sells a half million copies in its first year.

- No one has described Miles's music on "Bitches Brew" better than Jon Newey, who explains it is:

brain-melting, barrier-crunching music inside, "Bitches Brew" ripped up the rule book and redefined the parameters of jazz for the next three decades and then some. A colossal, unruly combination of electric jazz impressionism, dense funk rhythms, psychedelic rock flavors, and Stockhausen’s dark soundscapes, topped by some of Miles’s most stunning and evocative trumpet work. A jazz-rock volcano that spat controversy with every eruption.[26] (bold not in original)

John Coltrane (1926–1967)[edit]

-

In October, 1960 John Coltrane records material for three albums. The first one released, "My Favorite Things," features his recording debut on the soprano saxophone. "My Favorite Things," a highly modal piece, becomes a jazz favorite. Coltrane's quartet on this date includes McCoy Tyner (p), Steve Davis (b), and Elvin Jones (d). Two other albums recorded by Coltrane during these marathon October sessions were "Coltrane's Sound" and "Coltrane Plays The Blues."

In October, 1960 John Coltrane records material for three albums. The first one released, "My Favorite Things," features his recording debut on the soprano saxophone. "My Favorite Things," a highly modal piece, becomes a jazz favorite. Coltrane's quartet on this date includes McCoy Tyner (p), Steve Davis (b), and Elvin Jones (d). Two other albums recorded by Coltrane during these marathon October sessions were "Coltrane's Sound" and "Coltrane Plays The Blues."

-

Coltrane's "The Avant-Garde," dabbles in free jazz, released during 1960. Coltrane becomes interested in and influenced by Ornette Coleman and records Coleman's "The Invisible."

Coltrane's "The Avant-Garde," dabbles in free jazz, released during 1960. Coltrane becomes interested in and influenced by Ornette Coleman and records Coleman's "The Invisible."

-

May, 1961, John Coltrane records his last Atlantic record: "Ole," with Eric Dolphy (1935–1967), who joined Coltrane's band in 1961 performing as "George Lane."

May, 1961, John Coltrane records his last Atlantic record: "Ole," with Eric Dolphy (1935–1967), who joined Coltrane's band in 1961 performing as "George Lane."

-

Coltrane records "Impressions" and "Live at the Village Vanguard" (Impulse!) (1961). The musicians on "Impressions," released in November, include Eric Dolphy (bcl), McCoy Tyner (p), Reggie Workman and Jimmy Garrison (b) and Elvin Jones (d). The album's title tune is modal, but "India," approaches free jazz.

Coltrane records "Impressions" and "Live at the Village Vanguard" (Impulse!) (1961). The musicians on "Impressions," released in November, include Eric Dolphy (bcl), McCoy Tyner (p), Reggie Workman and Jimmy Garrison (b) and Elvin Jones (d). The album's title tune is modal, but "India," approaches free jazz.

-

During May and June, 1961, John Coltrane records "Africa/Brass" (Impulse!) with McCoy Tyner (p), Reggie Workman (b) and Elvin Jones (d).

During May and June, 1961, John Coltrane records "Africa/Brass" (Impulse!) with McCoy Tyner (p), Reggie Workman (b) and Elvin Jones (d).

-

John Coltrane records "Coltrane" (Impulse!) in April and June 1962 with McCoy Tyner (p), Jimmy Garrison (b) and Elvin Jones (d). Coltrane's classic quartet records "Ballads" (1962). Also in 1962 he records a number of live albums, including "Live At Birdland"(Charly) and "Bye Bye Blackbird" (OJC).

John Coltrane records "Coltrane" (Impulse!) in April and June 1962 with McCoy Tyner (p), Jimmy Garrison (b) and Elvin Jones (d). Coltrane's classic quartet records "Ballads" (1962). Also in 1962 he records a number of live albums, including "Live At Birdland"(Charly) and "Bye Bye Blackbird" (OJC).

-

John Coltrane – "A Love Supreme" (Impulse!) [Recorded 1964 & released in 1965] with John Coltrane (ts, v), McCoy Tyner (p), Jimmy Garrison (b), and Elvin Jones (d).

John Coltrane – "A Love Supreme" (Impulse!) [Recorded 1964 & released in 1965] with John Coltrane (ts, v), McCoy Tyner (p), Jimmy Garrison (b), and Elvin Jones (d).

-

In 1965, John Coltrane produces "Ascension," "Om," and "Kulu Sé Mama." These three large-group recordings feature high-energy collective free improvisaton. (later reissued as "The Major Works Of John Coltrane on Impulse!"). John Coltrane records "Sun Ship" in August, 1965 the final work by his classic quartet with McCoy Tyner (p), Jimmy Garrison (b), and Elvin Jones (d).

In 1965, John Coltrane produces "Ascension," "Om," and "Kulu Sé Mama." These three large-group recordings feature high-energy collective free improvisaton. (later reissued as "The Major Works Of John Coltrane on Impulse!"). John Coltrane records "Sun Ship" in August, 1965 the final work by his classic quartet with McCoy Tyner (p), Jimmy Garrison (b), and Elvin Jones (d).

-

"Meditations" (recorded in November 1965) expands his working quartet to a sextet with Pharoah Sanders (ts) and drummer Rashied Ali joining Elvin Jones.

"Meditations" (recorded in November 1965) expands his working quartet to a sextet with Pharoah Sanders (ts) and drummer Rashied Ali joining Elvin Jones.

-

Right before his death of liver cancer in 1967, Coltrane records "Stellar Regions," "Expression," and "Interstellar Space" and the live album "The Olatunji Concert."

Right before his death of liver cancer in 1967, Coltrane records "Stellar Regions," "Expression," and "Interstellar Space" and the live album "The Olatunji Concert."

Ornette Coleman (1930–2015)[edit]

![]() Ornette Coleman (1930–2015)

Ornette Coleman (1930–2015)

-

"Something Else!!!!" (1958)

"Something Else!!!!" (1958)

-

"Tomorrow Is the Question!" (1959)

"Tomorrow Is the Question!" (1959)

-

"The Shape of Jazz to Come" (1959) Ornette Coleman finishes "The Shape Of Jazz To Come" in July 1960 after starting it in October of 1959. The album features Ornette (as), Don Cherry (pocket tr), Charlie Haden (b), and Billy Higgins (d) on Atlantic Records.

"The Shape of Jazz to Come" (1959) Ornette Coleman finishes "The Shape Of Jazz To Come" in July 1960 after starting it in October of 1959. The album features Ornette (as), Don Cherry (pocket tr), Charlie Haden (b), and Billy Higgins (d) on Atlantic Records. -

"Change of the Century" (1960)

"Change of the Century" (1960)

-

"This Is Our Music" (1961) Ornette Coleman, "This is Our Music," (Atlantic Records) [Rec. August 1960 & released in 1961 with Ornette Coleman (as), Don Cherry (pocket trumpet), Charlie Haden (b), and Ed Blackwell (d).

"This Is Our Music" (1961) Ornette Coleman, "This is Our Music," (Atlantic Records) [Rec. August 1960 & released in 1961 with Ornette Coleman (as), Don Cherry (pocket trumpet), Charlie Haden (b), and Ed Blackwell (d).

-

"Free Jazz: A collective Improvisation" (1961) with Ornette (as), Don Cherry (pocket tr), Freddie Hubbard (tr), Eric Dolphy (bcl), Charlie Haden and Scott LaFaro (b) and Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins (d). One of the most important albums in free jazz.

"Free Jazz: A collective Improvisation" (1961) with Ornette (as), Don Cherry (pocket tr), Freddie Hubbard (tr), Eric Dolphy (bcl), Charlie Haden and Scott LaFaro (b) and Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins (d). One of the most important albums in free jazz.

-

"Ornette!" (1962)

"Ornette!" (1962)

-

"Ornette on Tenor" (1962)

"Ornette on Tenor" (1962)

-

"Chappaqua Suite" (1965)

"Chappaqua Suite" (1965)

-

"Town Hall" (Recorded 1962 & released 1965)

"Town Hall" (Recorded 1962 & released 1965) -

"The Empty Foxhole" (1966)

"The Empty Foxhole" (1966) -

"At the "Golden Circle" Vol. 1 & 2" (recorded 1965 & released 1966) with his new trio of bassist David Izenzon (1932–1979) and drummer Charles Moffett (1929–1997) on Blue Note Records.

"At the "Golden Circle" Vol. 1 & 2" (recorded 1965 & released 1966) with his new trio of bassist David Izenzon (1932–1979) and drummer Charles Moffett (1929–1997) on Blue Note Records. -

"New York Is Now!" (1968)

"New York Is Now!" (1968)

-

"Love Call" (1968)

"Love Call" (1968)

-

"Ornette at 12" (recorded 1968 & released 1969)

"Ornette at 12" (recorded 1968 & released 1969) -

"Crisis" (1969)

"Crisis" (1969)

![]() Charles Mingus in a 1960 interview comments regarding Ornette Coleman. “Now aside from the fact that I doubt he can even play a C scale . . . in tune, the fact remains that his notes and lines are so fresh. So when Symphony Sid (1909–1984) played his record, it made everything else he played, sound terrible. I'm not saying everybody's going to have to play like Coleman. But they're going to have to stop playing Bird. ” ("Another View of Coleman," Downbeat 27:11 (May 26, 1960): 21)

Charles Mingus in a 1960 interview comments regarding Ornette Coleman. “Now aside from the fact that I doubt he can even play a C scale . . . in tune, the fact remains that his notes and lines are so fresh. So when Symphony Sid (1909–1984) played his record, it made everything else he played, sound terrible. I'm not saying everybody's going to have to play like Coleman. But they're going to have to stop playing Bird. ” ("Another View of Coleman," Downbeat 27:11 (May 26, 1960): 21)

Superstars of jazz in 1960s America[edit]

NOTE: If a recording has two dates separated by a forward slash ("/"), then the first date is when it was recorded and the second date is its release. See the chart for musical instruments abbreviations.

![]() Vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson (1941– 2016) and saxophonist/flutist Harold Land (1928–2001) play together on "Total Eclipse" (Blue Note) (1968/1969) with Chick Corea (1941–2021) on piano, Reggie Johnson (1940–2020) on bass and Joe Chambers (b. 1942) on drums.

Vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson (1941– 2016) and saxophonist/flutist Harold Land (1928–2001) play together on "Total Eclipse" (Blue Note) (1968/1969) with Chick Corea (1941–2021) on piano, Reggie Johnson (1940–2020) on bass and Joe Chambers (b. 1942) on drums.

![]() Anthony Braxton (b. 1945) records "For Alto" (Delmark) (1969/1971), a 2-LP collection of solo saxophone improvisations.

Anthony Braxton (b. 1945) records "For Alto" (Delmark) (1969/1971), a 2-LP collection of solo saxophone improvisations.

![]() Charles Mingus (1922–1979) leads a quartet with reedman Eric Dolphy (1928–1964), trumpeter Ted Curson (1935–2012), and drummer Dannie Richmond (1931–1988) in 1960.

Charles Mingus (1922–1979) leads a quartet with reedman Eric Dolphy (1928–1964), trumpeter Ted Curson (1935–2012), and drummer Dannie Richmond (1931–1988) in 1960.

![]() Archie Shepp (b. 1937) records for the first time on "The World of Cecil Taylor" (1960/1961).

Archie Shepp (b. 1937) records for the first time on "The World of Cecil Taylor" (1960/1961).