Ontmusic0. What is music?

"Music is perhaps the art that presents the most philosophical puzzles." |

From the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "What is Music?" |

"The reasons for philosophers' attraction to music as a subject are obscure, but one element is surely that music, as a non-verbal, multiple instance, performance art raises at least as many questions about expression, ontology, interpretation and value, as any other art — questions that often seem more puzzling than those raised by other arts." |

"New Waves In Musical Ontology" Andrew Kania |

Contents

- 1 Discussion

- 2 Problems for Defining Music

- 3 Elements of Music

- 4 Definition of Music as Organized Sound

- 5 The Three Sirens Counter-Example to Music is Organized Sound

- 6 Music production requires intentional agents

- 7 A necessary condition for being music is a listenability condition

- 8 Jerrold Levinson's definition of music

- 9 Levinson's Means of Performance Condition

- 10 Objections to Means of Performance Being a Necessary Condition for Musical Works

- 11 Jerrold Levinson on Musical Works

- 12 Does music have any necessary conditions for qualifying as music?

- 13 Universals in Music

- 14 Internet Resources on Music

- 15 Music Bibliography

- 16 NOTES

Discussion[edit]

Problems for Defining Music[edit]

Reasons why music might not be definable[edit]

If music is an artificial and socially/culturally dependent entity conceptualized by semi-arbitrary choices, then there may well not be anything that exists that can be clearly delineated via definition other than just a grouping of what Wittgenstein might call family resemblances.

Andrew Kania (b. 1975), philosopher at Trinity University, raises a difficulty related to this kind of issue when he points out that music may well be too vague a concept/object thereby preventing anything like a specification of necessary and sufficient conditions:

“Another reason for the difficulty is that “music” is probably a vague concept, that is, one under which not everything either clearly falls or does not (perhaps because one or more of its necessary conditions is vague). On the one hand, this may helpfully allow us to classify disputed examples as “borderline cases.” On the other, there may be just as much dispute over whether a particular example is a borderline case or a clear one.”[1] (bold not in original)

Argument against the possibility of defining music[edit]

It is apparently easy to argue that because there is not a consensus on how to understand music across cultures that therefore there is no way to discover if music has a uniform and consistent nature such that it can be captured within a definition as the author of a music textbook affirms in the next quotations.

“20th-century composer John Cage thought that any sound can be music, saying, for example, "There is no noise, only sound." Musicologist Jean-Jacques Nattiez summarizes the relativist, post-modern viewpoint: "The border between music and noise is always culturally defined which implies that, even within a single society, this border does not always pass through the same place; in short, there is rarely a consensus . . . . By all accounts there is no single and intercultural universal concept defining what music might be."”[2]

But these are poor arguments. There is no consensus on moral values across cultures yet this does not prevent ethical theorists from arguing for the objectivity of moral standards. Neither does lack of consensus disbar scientists from seeking the objective nature of the quantum, or of what objectively constitutes a black hole. Disagreement amongst humans does not affect whether something does or does not have a consistent set of identity conditions that may or may not be capable of permitting effective definitions.

Jonathan McKeown-Green argues that music is only an institutionally practice-mandated kind and so not open to any final and definitive definition since it could always change in the future. For an evaluation and critique of his views see Ontdef3. What is the definition of jazz?: Assessment of the views of Jonathan McKeown-Green and Justine Kingsbury

“Music is an art form whose medium is sound and silence. Its common elements are pitch (which governs melody and harmony), rhythm (and its associated concepts tempo, meter, and articulation), dynamics, and the sonic qualities of timbre and texture. The word derives from Greek μουσική (mousike; "art of the Muses").

The creation, performance, significance, and even the definition of music vary according to culture and social context. Music ranges from strictly organized compositions (and their recreation in performance), through improvisational music to aleatoric forms. Music can be divided into genres and subgenres, although the dividing lines and relationships between music genres are often subtle, sometimes open to personal interpretation, and occasionally controversial. Within the arts, music may be classified as a performing art, a fine art, and auditory art. It may also be divided among art music and folk music. There is also a strong connection between music and mathematics. Music may be played and heard live, may be part of a dramatic work or film, or may be recorded.

To many people in many cultures, music is an important part of their way of life. Ancient Greek and Indian philosophers defined music as tones ordered horizontally as melodies and vertically as harmonies. Common sayings such as "the harmony of the spheres" and "it is music to my ears" point to the notion that music is often ordered and pleasant to listen to. However, 20th-century composer John Cage thought that any sound can be music, saying, for example, "There is no noise, only sound." Musicologist Jean-Jacques Nattiez summarizes the relativist, post-modern viewpoint: "The border between music and noise is always culturally defined—which implies that, even within a single society, this border does not always pass through the same place; in short, there is rarely a consensus . . . . By all accounts there is no single and intercultural universal concept defining what music might be.”

― "Music," in Sing for Joy Songbook: Singers Edition (bold not in original)

Reasons why music might be definable[edit]

Webster Collegiate Dictionary Online's definition of music: “The science or art of ordering tones or sounds in succession, in combination, and in temporal relationships to produce a composition having unity and continuity."

Is music a science? No, music is a product produced by musicians. Ordering sounds by combining them in succession to produce a continuous and unified sound composition would seem to be possible without producing music. See the three sirens counter-example discussed below, although it is unclear that any unified composition has been produced there.

On the other hand, anything that is a natural kind may well be definable precisely because natural kinds antecedently exist with whatever properties make the things be of that particular kind.

Music is a universal feature found in every human society and culture.[3] Because of the ubiquity of music, it may well be a 'natural' phenomena, just like gallbladders, gold, and consciousness. Arguably, someone could defend that any biological organisms with self-consciousness and physical and sensory abilities to manipulate sound are necessarily going to develop and have music.

➢ How might this argument proceed?

Self-conscious beings are necessarily aware of the external environment or they could not survive and reproduce. Because they are aware of the external environment, they must be able to notice and recognize the status and change of particular features in the environment. Being capable of noticing auditory changes and status in an environment is a possibly suitable way for aiding in survival and reproduction. Since self-conscious beings are both aware of the external world and able to reflect upon what occurs there and also what happens as a result of the self-conscious agent performing certain actions, a self-conscious being can easily relate to those auditory aspects that constitute the heart of all music, namely rhythm, melody, and harmony.

There is also theory and evidence supporting the position that humans find joint music-making leads to increased social cooperation perhaps aiding in reproduction and survival.

Elements of Music[edit]

- See "The Elements of Music" for a review of elements found in music.

- See also "Chapter 1 The Elements of Rhythm: Sound, Symbol, and Time: Introduction"

- "An Introduction to the Elements of Music"

Music has many distinguishable aspects and elements. Key elements of music include the following:

- Melody: Melody is a sequence of single notes; the main, most prominent line or voice in a piece of music, the line that the listener follows most closely. When accompanied, the melody is often the highest line in the piece and stands out. Melody is often the most memorable aspect of a piece.

- Rhythm: Notes of different durations organised into groups and placed in time often in relation to a pulse.

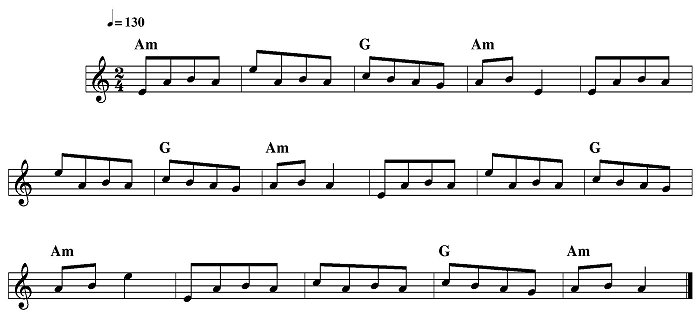

- Time: in music is organized in terms of the three fundamental elements of Pulse, Tempo, and Meter where pulse is the “beat” (the background pace of a piece of music), with tempo being the rate of relatively fast or slow speeds at which a pulse is perceived in a piece of music, while meters are ratios of durational values of notes assigned to represent a pulse organized in discrete segments in a piece of music. Pulse or beat are the regularly recurring underlying pulsations that has music progressing through time. Pulse makes persons react kinesthetically to music. In a piece of music, some durational values are assigned to be the pulse. All other durations are proportionally related to that fundamental background pulse. Tempo (Latin: tempos meaning time) is the rate (or relative speed) at which the pulse flows through time.

- Tempo: Tempo is the speed or pace of a given piece and is often indicated with an instruction at the start of a piece and usually measured in beats per minute (BPM).

- Meter: is expressed in music as a time signature and determines which durational value represents the fundamental background pulse, as well as how these pulses are grouped together in discrete segments or how they subdivide into lesser durational values, and the relative strength of pulses (perceived accents) within segments or groupings of pulses. Meter is the “ratio” of how many of what type of pulse values are grouped together. Simple Meter divides the pulse into two equal portions. Compound Meter divides the pulse into three equal portions. Meter is expressed as time signatures, indicating how many pulses (beats) are grouped together into cogent units.[4]

- Pulse equals the “beat,” with Tempo determining the “rate,” and Meter fixing the “ratio.”

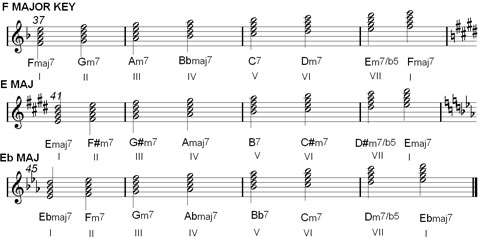

- Harmony: A series of chords (two or more notes played together) or a progression.

- Form: The structural patterns of an entire piece of music. Examples are binary form consisting of two distinct sections where normally each section repeats AABB, or ternary form with three sections where the third is a repeat of the first as in ABA form, or sonata form where there is an expansion of a binary form with the first section (exposition) introducing two or more themes, the first in the tonic, the second in the dominant or a closely related key. The next section (the development section) develops the themes in new keys, and the final section (the recapitulation) restates the themes, but ends in the original key. Sonata form emerged in the Classical period, and was often used for the first movement of solo sonatas, symphonies, chamber music and concertos.[5]

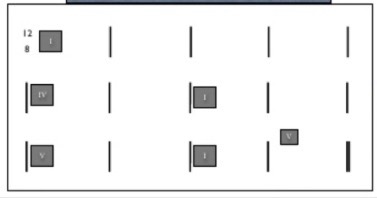

- 12 bar Blues Form:

- Timbre: The idiosyncratic and individualizing sound of each musical instrument. It can also refer to all the different sounds an instrument can make.

- Tonality: Scale(s) that the melody and harmony are derived from.

- Dynamics: Volume changes varying soft and loud.

- Texture: Texture is the relationships between the different ‘lines’ (instruments) within a piece.

- Scales: are sequential orderings of pitches built from small incremental distances called Tones and Semi-tones, but more commonly labeled whole steps and half steps with these serving as foundation scale-steps for building a scale.

- Monophonic: means there is only one line of music—one instrument or singer. There is no accompaniment or secondary melody. The term monophonic can be used for single lines—this could be solo, unision or octave doubling.

- Homophonic: literally means 'sounding together'. Homophonic music is based on chords. This can be a melody with a chordal accompaniment (melody dominated homophony) or where all parts have the same rhythm but different notes (such as a hymn tune). Homophonic music is also sometimes called chordal music.[6]

- The two sections below contain modified content from the BBC Bitesize learner guides review course in Music Theory taken by 15 and 16 year olds to mark their graduation from the Key Stage 4 phase of secondary education in England, Northern Ireland and Wales.

Music: has single notes played successively or combinations of simultaneously played notes known as chords.

Harmony: Notes played simultaneously produces what is termed harmony.

Chord: In music, chords are more than one note or harmonic pitches (typically three notes or pitches) played or heard as if sounding simultaneously.[7]

- Triads: Any chord of three notes is called a triad. An example of a triad is playing the notes C, E, and G simultaneously. This chord is known as a C major triad where C is the root note, E is the 3rd note on the scale, and G the 5th.

- Major and Minor Triads: The major triad has a major 3rd (for example, C – E – G) and the minor triad has a minor 3rd (C – E flat – G).

Dominant and Subdominant: In any major key, the chords built on the first, fourth and fifth degrees of the scale are all major. In the key of C, these are the chords of C, F and G. They are also sometimes called I, IV and V (for 1st, 4th and 5th in Roman numerals).

- Tonic: A chord built on the first note of the scale, I, is called the tonic.

- Subdominant: A chord built on the fourth note IV is called the subdominant.

- Dominant: Chords built on the fifth note V are called dominant.

Together these three kinds of chords are also known as the first, fourth and fifth degrees of the scale.

- Minor and Diminished: All the chords built on other notes in the scale of C are minor, except chord VII (the notes B D F) which is diminished.

- Sevenths: When a seventh is added to a chord this is known as a seventh chord. The dominant seventh of a V chord can be shown by the symbol V7. For an example G7 is made by taking the major triad of G (G – B – D) and adding an F (G – B – D – F).

Types of chords: A concord is a chord where all the notes seem to 'agree' with each other, it feels at rest and complete in itself whereas a discord is a chord where some notes seem to 'disagree' or clash giving an unsettled feel.

- Diatonic harmony uses notes which belong to the key.

- Chromatic harmony uses notes from outside the key to give the chords more 'color'.

The character of a piece of music is related to its key center or tonality.

- Tonal music is in a major or minor key whereas atonal music does not relate to a tonic note and therefore has no sense of key.

- Modal music uses modes which are seven-note musical scales. Two common musical modes are the Dorian mode and the Mixolydian mode. Modes are often used in folk music, pop music, or jazz.

Modulation: When a piece of music changes key it is said to modulate. When modulating often it is to a closely related key. The three most closely related keys to the tonic are the dominant, the subdominant or the relative minor or major keys.

Polyrhythm is when two or more rhythms with different pulses are heard together, for example, where one is playing in triple time and another is playing in quadruple time, three against four.

Triplets are three notes played in the time of two.

Cadences: A cadence is formed by two chords at the end of a passage of music.[8]

- Perfect cadences sound as though the music has come to an end. A perfect cadence is formed by the chords V - I.

- Interrupted cadences are 'surprise' cadences. You think you're going to hear a perfect cadence, but you get a minor chord instead.

- Imperfect cadences sound unfinished. They sound as though they want to carry on to complete the music properly. An imperfect cadence ends on chord V.

- Plagal cadences sound finished. Plagal cadences are often used at the end of hymns and sung to A-men. A plagal cadence is formed by the chords IV - I.

- Sometimes the final cadence of a piece in a minor key ends with a major chord instead of the expected minor an effect known as a Tierce de Picardie.

Definition of Music as Organized Sound[edit]

Many proposals have been presented as to how best to capture in a definition the true nature or essence of music. Several proposals concern themselves with variations on music being organized sound.

For example, that music is (mere) organized sound is stated in the very first paragraph of the first chapter (Part I: Tools — Notes, Rhythms, and Scales) of Hal Leonard's Keith Wyatt and Carl Schroeder, Pocket Music Theory: A Comprehensive and Convenient Source for All Musicians whose world famous publisher, Hal Leonard, glosses the book as “this handy pocket-sized book is the most contemporary music theory book on the market from the Harmony and Theory course at Musicians Institute in Southern California.”

“No matter what the style or complexity, music can be most simply described as organized sound; and the purpose of studying harmony and theory is to learn the methods by which sounds are organized in both large and small ways.”[9] (bold not authors)

Mirroring similar sentiments, classical and jazz performing author Mark Andrew Cook in his Music Theory states that a "coherent" and "safe" definition of music is that it is organized sound.

“In it’s broadest possible sense, music is defined as “organized sound.” This open-ended and safe definition is coherent regardless of era, style, culture, or the mechanics of musical organization. Each successive historical era produces musically artistic expressions of its own time, its own musical aura. The study of Music Theory is the means by which we investigate this.[10] (bold not in original)

At the Wikipedia discussion page on the definition of music several authors object to the definition of music as sound organized in time.

“I'm dissatisfied with the "sound organized in time" [definition for music] just because sounds can be organized in time incidentally, by natural phenomena, and I think most people would not call waves lapping at a beach music (though it is a pleasant enough sound). The same thing happens on man-made items, too, but often without musical intent: for instance, the puttering of a machine (which inspired at least Dave Brubeck to make something that most people agree is music). Also, humans sometimes organize sound in time for purposes other than music, for instance on various alarms. And suppose you have sounds organized in time in ways not intended: suppose a police cruiser and an ambulance go by at the same time in different directions; would that constitute music? What about a metronome itself--sound organized in time, with a recent and specific, music-related human intent. Would a metronome by itself be considered music? I'm not sure if human, music-oriented intent is an accepted component of the definition of music or not; and in fact opinions about it may vary widely.”[11] (bold not in original)

Fleeb suggests that one might rectify the inadequacies of the music defined as organized sound by adding "as a form of art."

“The "sound organized in time" definition [should be modified to] music is a form of art which organizes sound in time. Or, perhaps worded another way, music is a form of art that uses sound organized in time as its medium. This would remove sirens, lapping waves, and so on, without stripping them out if they were used with musical intention.[11] (bold not in original)

The problem with this last addition is that it may amount to the equivalent of adding "when it is music." Suppose it is not a form of art. Can I play organized sounds in time that is not music. Yes. What now needs to be added so that these organized sounds are now a form of art. Suppose we take the non-music organized sounds discussed below in the three sirens counter-example and have them played inside a museum as a work of art. Would this change the organized sounds in time as sounds now that they are being exhibited in a museum? Not necessarily, therefore if they were not music before they got stuck in a museum, they would not now be music when they are being produced inside of a museum as a work of art. Being a work of art does not make sounds be music because works of non-musical art can exist. Someone can have a work of art made from sounds that do not constitute music, such as a hammer hitting an anvil once every 59 minutes. This could be a work of art with organized hammer strikes producing a sound in time every 59 minutes. No one should think this is music even though it is organized sound as an art form and neither the artist nor the museum intended it to be music either. Even if the artist did intend it to be music doesn't make it that it must then be music, any more than when an artist intends his statue to exemplify a light airy appearance that it must have this feature. His or her intention could fail and the statue instead looks heavy.

CONCLUSION: The proposed definition of music as a form of art that uses organized sounds is not a sufficient condition for music and therefore is not a successful definition of music.

Immediately one considers what other possible counter-examples there might be to such proposals. We know what form the counter-example would take. Find something that intuitively and with arguments is not music, yet remains organized sound.

➢ For what purposes other than music making might one want to organize sound?

Before one tries to answer this question it would be appropriate first to clarify what one means and how one uses the concept of organization.

➢ What is required for anything to have been organized?

The Nature of Organizing[edit]

Dictionaries define the word "organize" to mean:

- To form into a coherent unity or functioning whole.

- Integrating elements together.

- To set up a structure.

- To arrange by systematic planning and united effort.

- To arrange elements into a whole of interdependent parts.

- To put in order; arrange in an orderly way.

- To cause to have an orderly, functional, or coherent structure.

- To develop into or assume an orderly, functional, or coherent structure.

- Arranging several elements into a purposeful sequential or spatial (or both) order or structure.

- Organizing is a systematic process of structuring, integrating, co-ordinating task goals, and activities to resources in order to attain objectives.

Apparently, the function or purpose of organizing would seem to be the creation of structure, often of some completed structure known as a whole (structure).

What is Structure?[edit]

- Oxford Dictionaries defines structure when used either as a noun or as a verb:

- NOUN - The arrangement of and relations between the parts or elements of something complex.

- VERB - Construct or arrange according to a plan; give a pattern or organization to.

- Structure is "the manner of construction of something and the arrangement of its parts."

Given that organizing functions to produce structure, then if music is organized sound, then music is produced by structuring sound.

➢ What sort of activities would count as organizing structured sound?

The Three Sirens Counter-Example to Music is Organized Sound[edit]

Because structure results from arranging parts of a non-simple whole a single sound by itself, because it is simple in the required sense, could not qualify as having been organized sound. Therefore, a siren's whistle by itself with one note could not count as a counter-example to the definition of music as organized sound since it isn't organized. This means that a single one note siren cannot count as music.

Suppose though that at a hypothetical factory the management uses three siren whistles where one announces breaktime and one of the other two sounds to indicate whether the food truck or the ice cream truck is outside. Siren D(o) indicates breaktime. Siren R(e) announces food truck arrival, while siren M(e) indicates the ice cream truck is present. When all three things are present (breaktime, food truck, and ice cream truck) all three sirens might blow one after another. Suppose the three sirens sound like Do Re Me. We now have organized sound with the three siren whistles under any one's definition of organizing, but would this now qualify as music production?

Why the Three Sirens are Organized Sound[edit]

An argument that the three siren whistles do not count as music, while nevertheless remaining organized sound is this. We have already agreed that no one siren as a single tone by itself counts as music. Since each siren is distinct and the sirens can go off with a one minute gap of silence between each one, then the series of sirens cannot count as music since each one by itself cannot be music. With a one minute gap, most perceivers would perceive this as three separate sonic events and would not experience these three sirens as music. However, isn't it obvious that these three sirens whistles have been organized because using either the noun or verb use of "organize" the three sirens qualify.

Consider as a:

- NOUN - The arrangement of and relations between the parts or elements of something complex.

The three sirens are complex as individuals and as a three part whole. The factory manager has arranged them to sound different so as to signal different things. They still have relations between the parts in that each is a note apart because they sound like Do, Re, Me (not to mention their relationships amongst themselves by each being physically a siren). They are also related in that each is a signal at the same factory and have been so arranged, therefore they count as organized sound.

Consider as a:

- VERB - Construct or arrange according to a plan; give a pattern or organization to.

Clearly, the three sirens have been arranged according to a plan. There are distinct patterns of sounds, and, if one wishes for a more complex pattern, the three signals of breaktime, food truck, or ice cream truck could be signaled with two siren blasts one quickly following the other using this schema:

- Siren D (sounds like Do), Siren R (sounds like Re), and Siren M (sounds like Me).

- Signals meaning: DR = Breaktime, RM = food truck here, MD = ice cream truck here

Hence, these sirens have been given a pattern of two notes and have been so structured, therefore counting as organizing sound.

Why the Three Sirens (and Mere Organized Sounds) are not Music[edit]

It is quite unlikely that any factory worker ever comments upon how much she or he enjoys the music that is played to indicate breaktime, or arrival of the food or ice cream trucks. Why? There are several reasons that come to mind why factory workers would not perceive or experience any two blasts of the sirens as music.

- The sirens serve the sole purpose of indicating the status of things at the factory and are not present for entertainment purposes. Music typically entertains.

- The sirens were not intended by anyone involved in the causal processes that set up the factory sirens to count as or be music. It is possible, even likely, that the sound of each siren was intended to sound relatively pleasing and not harsh so as not to annoy anyone who has to listen to them day after day. So, one might describe the sounds of Siren D followed by Siren R as musicalish sounding. What one means by musicalish sounding is that it is not unpleasant to the ear and the Do Re is a familiar part of music.

It doesn't follow that any two sirens sounding counts as a very short tune. The burden of proof here is on anyone who wishes to argue that the Do Re siren signal qualifies as music. One needs more of an argument for why the two sirens qualify as music than just the theory that music is organized sound or you would be begging the question against your opponent who is claiming the opposite--conceding it is organized sound, but denying it is music.

Conclusion: Music is Not (Mere) Organized Sound[edit]

Since no one would dispute that a siren whistle counts as a sound, and that the siren examples count as organized, yet the sirens aren't music, then the simple definition of music as organized sound has been refuted.

That music cannot be mere organized sound is well-known by philosophers as pointed out in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

“Explications of the concept of music usually begin with the idea that music is organized sound. They go on to note that this characterization is too broad, since there are many examples of organized sound that are not music, such as human speech, and the sounds non-human animals and machines make.”[12]

Philosopher Stephen Davies  of the University of Auckland agrees that 'organized sound' is at best only a necessary condition for something to be music and is definitely not a sufficient condition since all language utterances are non-music yet remain organized sounds.

of the University of Auckland agrees that 'organized sound' is at best only a necessary condition for something to be music and is definitely not a sufficient condition since all language utterances are non-music yet remain organized sounds.

“Most common, simple definitions of music do not meet this standard. For instance, the suggestion that music is "organized sound" identifies a condition that is, at best, only necessary. Any linguistic utterance satisfies this condition, so satisfying it cannot be sufficient for something's being music.”[13] (bold not in original)

Music production requires intentional agents[edit]

If this Wikipedia entry is taken seriously, that music is an artifact made by and within cultures, which is entirely unargued for and merely asserted, then we may have an answer about why nature can never produce music, but only sounds. Non-biological Nature lacks intentional agents and without such agents culture is impossible. If culture is required for both music production and musical performances, then nature can neither produce nor perform music.

➢ What is culture and why is culture necessary for musical production?

Why intentional production of organized sounds is insufficient for music production[edit]

Sound designers and sound manipulators and sound editors exist. A sound designer or sound editor intentionally manipulates and organizes sounds without the output resulting in any music. One easy way to prove this is by demonstration. A sound editor might decide different timings as to when firecracker sounds go off during a scene in a movie. The editor fixes two different tracks with one having a slower firing of the firecrackers than another one. Both the slow and the fast clips consist of intentionally produced and edited organized sound but no one will judge either of these firecracker scenes as having played music.

CONCLUSION: Intentional production of organized sound is not sufficient for music production.

➢ What is missing such that were it to be added then music production necessarily occurs?

CANDIDATES FOR ADDITIONS:

Candidate #1: Rhythm

The moment that rhythm is tasked intentionally into account and the sound sequences, parts, notes, phrases are intentionally organized so as to effect an intentional rhythm then one has created music from the sound designers components that previously were not music, although they had been intentionally organized sound. As a consequence, if a sound designer were to take and add rhythmic effects such as 1 anda 2 anda 3 anda 4 then 1 anda anda 2 etc with regular repeating of a consistent rhythm with the intention to make the organized sounds into music, then he would be successful. Rhythmic aspects that could be intentionally manipulated include tempo, meter, and articulation.

A rhythmic beat can be created by contacting two items together to form a repeating pattern of long and shorts sounds known as the rhythm. In music, every melody has a rhythm, or pattern of long and short beats. A memorable melody will usually have a simple, yet interesting rhythm.

Candidate #2: Melody

A melody is a linear sequence of musical tones/notes, literally a combination of pitch and rhythm, making up a musical phrase that listeners perceives as a single entity.

The first most famous professor of music was Eduard Hanslick (1825-1904).

“First published in 1854, On the Musically Beautiful is often referred to as the foundation of modern musical aesthetics. As such claims are typically overstated, it is probably best to consider it the codification of such notions of musical autonomy and organicism. These ideas proliferated in academia, in which he was the first professor of music history and aesthetics. Importantly, while this text certainly lays the theoretical groundwork for musical formalism, formal analysis is something that Hanslick himself never did.”[14] (bold and bold italic not in original)

“If one inquires into the extent to which nature provides material for music, it turns out that nature does this only in the most inferior sense of supplying the raw materials which mankind makes into tones. Mute ore from the mountains, wood from the forests, the skin and entrails of animals, these are all we find in nature with which to make the proper building materials of music, namely, pure tones. Thus initially we receive from mother nature only material for material; this latter is the pure, measurable tone, determined according to height and depth of pitch. It is the prime and indispensable requisite of all music. It forms itself into melody and harmony, which are the two principal factors of music. Neither is encountered in nature: they are creations of the human spirit.

Not even in the most rudimentary form do we perceive in nature the orderly succession of measurable tones which we call melody.. Nature's successive auditory phenomena are lacking in intelligible proportion and evade reduction to our major and minor scales. But melody is the jumping-off point, the life, the original artistic manifestation of the realm of sound; all additional determinations, all inclusion of content, are tied to it. just as little as melody does nature (which itself is a marvellous harmony of all phenomena) know harmony in the musical sense, i.e., as the sounding together of well-defined tones. Has anyone ever heard a triad in nature? A chord of the sixth or seventh? Like melody, harmony (though in a much slower evolution) is a product of the human spirit.

The Greeks knew no harmony but sang at the octave or in unison, just as at present those Asiatic people do among whom singing is to be found. The use of dissonances (among which are the third and the sixth) developed gradually, beginning in the twelfth century, and until the fifteenth century music was restricted to modulations upon the octave. The intervals which now come under the rules of our harmony must have been acquired one by one and sometimes took a whole century for so modest an achievement. The most artistically advanced people of antiquity, just like the most learned composers of the early Middle Ages, did not know what our shepherdesses in the remotest Alps know: how to sing in thirds. It is not the case, however, that harmony came along and shed a whole new light on music; on the contrary. it has been there from the first day. The whole tonal creation existed from that moment," said Nageli.

Accordingly, harmony and melody are not to be found in nature. Only a third element in music, this one being supported by the first two, existed prior and external to mankind: rhythm. In the gallop of the horse, the clatter of the mill, the song of blackbird and quail, a unity is displayed into which successive particles of time assemble themselves and construct a perceivable whole. Not all but many manifestations of nature are rhythmic. And of course supreme in nature is the law of duple rhythm: rise and fall, to and fro. What separates this natural rhythm from human music must be immediately evident. That is to say, in music there is no isolated rhythm as such, but only melody and harmony, which are manifested rhythmically. In nature, on the contrary, rhythm conveys neither melody nor harmony, but only incommensurable vibrations in the air. Rhythm, the sole musical element in nature, is also the first thus to be awakened in mankind, and the earliest to develop in children and animals. When the South Sea Islander bangs rhythmically with bits of metal and wooden staves and along with it sets up an unintelligible wailing, this is the natural kind of "music," yet it just is not music. But what we hear a Tyrolean peasant singing, into which seemingly no trace of art penetrates, is artistic music through and through. Of course, the peasant thinks that he is singing off the top of his head. For that to be possible, however, requires centuries of germination.

So we have considered the necessary basic ingredients of our music and have found that humankind did not learn from the natural surroundings how to make music. The history of music teaches how and in what sequence our present-day system developed; we have presupposed this. Here we need only keep in mind that melody and harmony have emerged slowly and gradually as creations of the human spirit, as have also our intervallic relationships and scales, the separation into major and minor according to the different placements of semitones, and finally the system of equal temperament, without which our western European music would not have been possible. Nature has endowed mankind only with the organs and the desire for singing and with the ability to construct a tonal system, bit by bit, upon the basis of the simplest relationships (the triad, the harmonic series). These alone will continue to be the changeless foundations of any further construction. One should be on guard against the error of thinking that this tonal system (our present one) necessarily exists in nature. That naturalists nowadays, as a matter of course, casually treat musical relationships as if they were natural forces in no way stamps the laws governing music as natural laws; this is a consequence of our endlessly expanding musical culture. Hand observed quite rightly that for this reason even our children, while still in the cradle, already sing better than mature savages. "If the diatonic scale existed in nature, every human would always sing in tune, and always perfectly."

When we call our tonal system "artificial," we use this word not in the refined sense of something fabricated at will in a conventional manner. We mean it to designate merely something in the process of coming into being, in contrast to something already created by God. Hauptmann overlooks this when he calls the notion clan artificial tonal system "totally invalid," in that "musicians could just as little have determined the intervals and invented a tonal system, as linguists (Sprachgelebrien] could have invented the words and syntax of a language." Language is an artifact in exactly the same sense as music, . . . . [15] (bold not in original)

Candidate #3: Dynamics

As pointed out at Wikipedia dynamics in music are “the variation in loudness between notes or phrases. . . . The execution of dynamics also extends beyond loudness to include changes in timbre and sometimes tempo rubato.”

If a sound designer starts with sounds she has designed that are not music and then purposefully uses a humanly recognizable repeating pattern of dynamic loudness and softness, then it may well be that people could perceive this as musical at the very least if not just outright an idiosyncratic or unusual form of music.

dynamics (loudness and softness)

common elements of music are pitch (which governs melody and harmony), rhythm (and its associated concepts tempo, meter, and articulation), dynamics (loudness and softness), and the sonic qualities of timbre and texture (which are sometimes termed the "color" of a musical sound). Different styles or types of music may emphasize, de-emphasize or omit some of these elements.

➢ Meno's paradox (or, the learner paradox): how can you seek to find that which you do not already know?[16]

Correspondingly, how can musicians know that they are playing music (and be playing it) without having to know what is music?

How can musicians have an intention to be playing music if they do not know how to define music? What makes this possible? How can the word "music" or "jazz" have as its referent jazz if jazz does not exist as a genre of music? How can words refer to nebulous objects? How does the reference of the word "dog" succeed in including all and only dogs?

➢ How can someone intend something if they don't know what is the thing that they are intending?

Consider some examples to seek more clarity. Suppose Fred intends to go to the bus stop. Must Fred know what bus stops are? Well, Fred does know some things about them. Bus stops are geographic locations organized often as locations on the surface of the Earth where public transportation vehicles make regular stops to pick up and let out passengers. Knowing this much explains what the person intending to go to his or her bus stop ought roughly to know regarding having an intention to go to this stop to catch a bus.

➢ Does Fred need to know what is a bus to catch and ride one?

Not really. Very minimal descriptions of things would meet with his intention to catch a bus. If a giraffe shows up for transport then Fred may well be surprised because a giraffe for transport was outside of the means he had thought the bus service might be providing. If instead of a giraffe, a solar powered bus, or a diesel powered one, or a gas powered bus would all meet with and satisfy Fred's intention to catch a bus. His intention is quite open ended. It stops short probably of including having to ride a bicycle to work from the bus stop, but if a cycle rickshaw  shows up and it was sent by the bus company to provide public transportation Fred might not object to this situation and accept it as meeting his original intention to catch a bus.

shows up and it was sent by the bus company to provide public transportation Fred might not object to this situation and accept it as meeting his original intention to catch a bus.

CONCLUSION: Intentions can be successful without the intender needing to have a complete picture of the situation nor does it require complete knowledge of the objects intended.

➢ What are the implications of this conclusion regarding philosophical issues in jazz?

One implication is that jazz musicians can intend to be playing jazz without needing to know everything about jazz and in particular can intend to be playing jazz yet not able to define it, i.e., not being able to answer the question "What is jazz?".

A further objection, pointed out by Andrew Kania in his Stanford Encyclopedia entry on "The Philosophy of Music," to any claim that music is organized sounds is that music also incorporates non-sounds into music.

“Most theorists note that music does not consist entirely of sounds. Most obviously, much music includes rests.”[17]

Perhaps as a consequence of the existence of non-sounds in music, namely rests, it is possible to compose music without any sounds at all involved, only rests. If possible, then this is a fundamental objection to music being organized sounds if music exists that uses no sounds. Again, Andrew Kania in his "Silent Music" argues that there already exists such music that lacks sounds, and he gives several examples with the most prominent being Erwin Schulhoff’s Fünf Pittoresken published in 1919. It is the middle movement of this five part suite that interests us, “In futurum,” which you cannot listen to here because it consists entirely of rests, but you can see him (not) play it.[18]

A necessary condition for being music is a listenability condition[edit]

To convince someone that music necessarily satisfies a listenability condition, where this listenability conditions still remains to be fleshed out as to what it requires or does not require, consider sounds that are made not to be listenable to.

Two candidates come immediately to mind: Muzak and anti-noise/noise cancellation.

- Muzak is music purposefully designed not to be noticed as music. Instead it is intentionally designed so as not to be noticed as music. Rather it is the sonic events that are functionally equivalent to cows milk production increasing when played soothing music. If we presume that the cows milk production could be equally well improved using soothing non-music, then Muzak is similarly designed to improve workers performance without the workers having to have any cognitive attention to these sonic events as music.

- Anti-Noise/Noise cancellation occurs when the exact opposite sound waves are produced so as to neutralize an incoming sonic situation as used in noise cancelling headphones on airplanes ✈️. When one sound source has a peaking wave while another has a trough the two waves cancel each other out leaving relative silence. Clearly the cancellation counts as a sonic event or the cancellation effect could not occur, but nobody believes lack of noise in this situation will count as music production. If any thing it is anti-music production if used to cancel out the musical sounds.

Jerrold Levinson's definition of music[edit]

Levinson's Means of Performance Condition[edit]

This refutation of the simple version of music as organized sound motivates the need for a further condition that would rule out the siren counter-examples. Jerrold Levinson in his "What A Musical Work Is" finds problematic any theory that merely claims music to be a sound structure:

“The most natural and common proposal on this question is that a musical work is a sound structure--a structure, sequence, or pattern of sounds, pure and simple. My first objective will be to show that this proposal is deeply unsatisfactory, that a musical work is more than just a sound structure per se.”[19]

He thinks there needs to be an additional aspect to any proposal that music consists of sound structure--it also necessarily involves a means of performance structure:

"I propose that a musical work be taken to involve not only a pure sound structure, but also a structure of performing means. If the sound structure of a piece is basically a sequence of sounds qualitatively defined, then the performing-means structure is a parallel sequence of performing means specified for realizing the sounds at each point. Thus a musical work consists of at least two structures. It is a compound or conjunction of a sound structure and a performing-means structure."[20]

➢ What does Levinson mean by means of performance structure?

He explains:

"To regard performance means as central to musical works is to maintain that the sound structure of a work cannot be divorced from the instruments and voices through which that structure is fixed, and regarded as the work itself."[21]

Levinson concludes that all musical works are types with these three features: creatability, individuated by historical context, and include means of performance.

" . . . what are [musical works]? The type that is a musical work must be capable of being created, must be individuated by context of composition, and must be inclusive of means of performance."[20]

Objections to Means of Performance Being a Necessary Condition for Musical Works[edit]

Objection from Sonicism[edit]

Julian Dodd, in his role as defender of Sonicism vigorously objects to performance means being required for the existence of a musical work. A sonicist holds that the only relevant features of all musical works are acoustical/sonic properties. This entails that if two musical works sound alike, then they are identical musical works regardless of their means of production. If one performance uses a violin and another sonically equivalent performance uses a synthesizer, then Dodd's Sonicism requires these two tokens be of the very same musical type/work.

Objection from Common Sense[edit]

Common sense, which cannot be automatically trusted because it can be wrong, would not agree that each and every musical work is attached to or required only to be performed using some given and previously determined musical generating instruments. If someone composes a song on a piano this doesn't mean the composer couldn't be writing a piece of music intended to be played on a trumpet. To show the absurdity of the means of performance requirement consider the following scenario and it's absurd implications if performance means is attached to each musical work.

Suppose a composer is given a contract to write a musical work intended to be played only on a trumpet. The composer even titles his composition "Only To Be Played Using a Trumpet." When the composer completes the composition for trumpet on the piano and plays it through once to see what it sounds like on the very piano he used to compose the work, according to the means of performance requirement, the composer did not just play his own composition, but some other one. This strikes common sense as absurd since common sense says the composer just played his own composition written to be played using a trumpet, but instead using a piano. If he didn't just play "Only To Be Played Using a Trumpet," then what did he play? Common sense has no answer to this question so maintains he must have played "Only" on piano because there is no other answer to what was played.

Objection from Invention of New Musical Instruments[edit]

Because new musical instruments can be invented no composers could specify in advance the specific musical instruments that might be used to play their compositions in the future. Even if a musical work was originally designated to be played using a specific set of instruments it is common practice to use different ones and still claim the new instruments are playing that particular musical work.

Cannot many different songs originally played with other instruments be played on a harmonica? If you think they can, then this is at odds with musical works requiring performance means of only a limited, specific set of instruments as part of the work itself.

Who is the determiner of what performance means are required for any particular work? It cannot be the composer because in some instances composers write a melody without having any particular performance means in mind. Yet the completed melody is itself a musical work prior to any specification of by what means the melody could be played.

Notes themselves and rhythmic relationships of sounds amongst themselves do not require any specific performance means. A middle C can be played on many different instruments. Even if we restrict ourselves to playing middle C on two pianos they each will have produced a middle C sound, but because of different physics of sounding boards and string elements, the two middle C's could be acoustically different (sounding).

Reductio Ad Absurdum of Performance Means Requirement[edit]

- It is possible to compose a musical work with no particular or specific set of instrumentation determined by anyone as to how this musical work could be performed.

- A Performance Means requirement entails it is impossible to have such a performance means less musical work. An implication of this would be that no musical work has yet to be created since no performance means has been specified.

Both of these positions cannot be correct because they contradict each other.

➢ How does one decide which is correct without begging the question against the other?

Performance Means is Relevant to Musical Works[edit]

Beethoven's Fifth Symphony cannot be played on a harmonica. At best a harmonica player could try playing what is taken for the melody of the Fifth. What would be missing are the symphony's other essential harmonic features, especially counter-melodies or any musical effects dependent on more than a single musical instrument.

Jerrold Levinson on Musical Works[edit]

In "Evaluating Musical Performance" Jerrold Levinson defines a musical work as requiring an intentional production. Here are his definitions of a musical work and of a musical performance:

"I will mean by an instance of a work a sound event, intentionally produced in accord with the determination of the work by the composer, which completely conforms to the work's sound and instrumental structure as so determined. By a performance I will mean the product of an attempt to produce for aural perception and appreciation something which is more-or-less an instance of a work and which more-or-less succeeds in doing so.”[22] (Italics author's; bold not)

Does music have any necessary conditions for qualifying as music?[edit]

Philosophers have tried to find additional components besides organized sound that makes these sounds qualify as music. There have been two main approaches using either or both of a tonality condition and/or an aesthetic properties conditions.

“There are two further kinds of necessary conditions philosophers have added in attempts to fine tune the initial idea. One is an appeal to ‘tonality’ or essentially musical features such as pitch and rhythm (Scruton 1997[23]; Hamilton 2007[24]Kania 2011a[25]). Another is an appeal to aesthetic properties or experience (Levinson 1990b)[26]; Scruton 1997 [27]; Hamilton 2007[28]). As these references make clear, one can endorse either of these conditions in isolation, or both together. It should also be noted that only Jerrold Levinson and Andrew Kania attempt definitions in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions. Both Roger Scruton and Andy Hamilton reject the possibility of a definition in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions. Hamilton explicitly asserts that the conditions he defends are ‘salient features’ of an unavoidably vague phenomenon.”[29] (bold, italic, and bold italic not in original)

Following the investigation of both tonality and aesthetic features as necessary conditions for music's existence, a third candidate for a necessary condition will be considered: intentionality of music production.

Tonality Necessary Conditions[edit]

Any tonality necessary condition requires that only basic musical features such as melody, rhythm, or harmony be appealed to in defining the nature of music.[30]

In his Philosophy of Music article for the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Andrew Kania explains what defenders of the tonality condition have had to resort to:

“The main problem with the first kind of condition is that every sound seems capable of being included in a musical performance, and thus characterizing the essentially musical features of sounds seems hopeless. (We need only consider the variety of ‘untuned’ percussion available to a conservative symphonist, though we could also consider examples of wind machines, typewriters, and toilets, in Ralph Vaughan Williams's Sinfonia Antartica, Leroy Anderson's The Typewriter, and Yoko Ono's “Toilet Piece/Unknown”.) Defenders of such a condition have turned to sophisticated intentional or subjective theories of tonality in order to overcome this problem.”[31] (bold and bold italic not in original)

Kania points out the key problem for any defenders of any kind of tonality conditions (musical features) is that musical performances are capable of potentially incorporating any sound into a musical performance. As a consequence, these defenders have had to resort to fairly sophisticated theories of tonality. The reason for such sophistication is to prevent such tonality theories from permitting non-music to count as music. We all know that jackhammers on the job site are not musical sounds. Nevertheless, a musician could incorporate such sounds into a musical performance, as was mentioned in Kania's quotation above of incorporating wind machines, typewriters, or flushing toilets.

“Rhythm, melody, harmony, timbre, and texture are the essential aspects of a musical performance. They are often called the basic elements of music. The main purpose of music theory is to describe various pieces of music in terms of their similarities and differences in these elements, and music is usually grouped into genres based on similarities in all or most elements. It's useful, therefore, to be familiar with the terms commonly used to describe each element. Because harmony is the most highly developed aspect of Western music, music theory tends to focus almost exclusively on melody and harmony. Music does not have to have harmony, however, and some music doesn't even have melody. So perhaps the other three elements can be considered the most basic components of music.”[32] (bold not in original)

“Music cannot happen without time. The placement of the sounds in time is the rhythm of a piece of music. Because music must be heard over a period of time, rhythm is one of the most basic elements of music. In some pieces of music, the rhythm is simply a "placement in time" that cannot be assigned a beat or meter, but most rhythm terms concern more familiar types of music with a steady beat.”[33] (bold not in original)

Aesthetic Experience Necessary Conditions[edit]

Because of the possibility of non-music sounds being possibly incorporated into a musical performance philosophers turned to using some sort of aesthetic conditions or experiences for characterizing what makes certain sounds qualify as music. Still, this approach bears its own problems if having some non-musical sounds qualify as falling within whatever aesthetic experiences are used to pick out all and only music. The aesthetic experience that fails to be music, but still has aesthetic properties related to its sounds, is poetry.

“If one endorses only an aesthetic condition, and not a tonality condition, one still faces the problem of poetry – non-musical aesthetically organized sounds.”[34]

Poetry reveals that the aesthetic properties net is too wide because it captures and includes poetry. An additional problem for the aesthetic properties approach is that it may also be too narrow since it excludes musical scales as well as Muzak from qualifying as music because these two lack sufficient (appropriate) aesthetic properties. Kania points out how these factors affect Andy Hamilton's aesthetic approach to defining music.

“This is one reason Hamilton endorses both tonal and aesthetic conditions on music; without the former, Levinson is unable to make such a distinction. On the other hand, by endorsing an aesthetic condition, Hamilton is forced to exclude scales and Muzak, for instance, from the realm of music.”[34]

Now this may not be as bad as it seems.

➢ Do scales count as music by themselves? Perhaps scales are too uninteresting to count as music.

Wikipedia on (musical) scales defines a scale as:

“In music theory, a scale is any set of musical notes ordered by fundamental frequency or pitch. A scale ordered by increasing pitch is an ascending scale, and a scale ordered by decreasing pitch is a descending scale.”[35]

So right away there is a problem in that Wikipedia defines a scale as consisting of musical notes. When these notes are played one produces a series of musical notes. Isn't this what happens in any performance of music? If so, scales, with their relative lack of aesthetically appealing properties, may possibly still qualify as music even if not very interesting or aesthetically appealing music; similarly with Muzak.

Furthermore, on the face of it, no matter how mundane and droll Muzak remains, it seems on the surface at least to still count as music even if quite bad and horrible music thereby posing a problem for any aesthetic conception of what makes something qualify as music.

Intentionality Necessary Conditions for Music[edit]

While it remains unclear the best way to characterize the intentions of composers and performers when generating music because it remains unclear precisely what they are intending, the intuitive idea that intention is a necessary condition for music production remains an attractive prospect.

For example, Andrew Kania appeals to an intentionality requirement for the existence of music when he denies that music can exist that wasn't intended to be music.

First, here is Kania's definition of music.

“Music is (1) any event intentionally produced or organized (2) to be heard, and (3) either (a) to have some basic musical feature, such as pitch or rhythm, or (b) to be listened to for such features.”[34] (bold not author's)

Second, here is where Kania denies something is music, where the sonic situation remains unchanged, but the status of the sonic event as music can come and go dependent upon intentionality considerations.

“This definition [quoted above] allows me to make a distinction unavailable to [Jerrold] Levinson. There are artists who characterize themselves, or are characterized by others, as “sound artists.” These are artists who produce sounds for what we might call artistic or aesthetic appreciation, but who, like Cage, more or less explicitly intend us to listen to these sounds not under musical concepts, but more purely as the sounds as they are “in themselves.” We can imagine a musical pair of Dantoesque “indiscernibles”: two works that use the same “found sound” (say, a field recording of a construction site), one of which is intended to be listened to under basic musical concepts, the other of which is not. The former, I would argue, is a piece of music; the latter is not—it is non-musical sound art.”[34]

For an extensive discussion of the relevance of intention to musical production see PoJ.fm's Ontmusic3. Sections §7-13, especially §13 Why Intentional Agency is Necessary for Music Production at Ontmusic3. What is a song?.

Universals in Music[edit]

- Kathleen Marie Higgins (University of Texas at Austin), "The Cognitive and Appreciative Import of Musical Universals."[36]

- John W. Longo, “Why Can Sounds Be Structured As Music?” in Teorema: Revista Internacional De Filosofía, vol. 31, no. 3, 2012, 49–62. Jstor's "Why Can Sounds Be Structured As Music?".

- Musical Notation

- On Beats and Meter

- Understanding Musical Meter

Internet Resources on Music[edit]

- Enhanced Bibliography on philosophy of music Bibliographic References to "What is Music? by Andrew Kania in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy on "What is music?"

- Wikipedia on Defining Music

- "Muzak and Background Art" by Mike of hyperreal.org from ESTWeb, the World Wide Web homepage for EST Magazine.

- "The Soundtrack of Your Life: Muzak in the realm of retail theatre," by David Owen in The New Yorker Magazine, April 10, 2006.

- What is Music? by Marcel Cobussen with discussion by others

- Elements of Music by Espie Estrella

- Jazz Harmony: From Origins to Jazz by Martin Antaya.

- Nicholas Cook, Chapter 17: "Music as Performance," in Cultural Study of Music: A Critical Introduction, edited by Martin Clayton, Trevor Herbert, and Richard Middleton (New York: Routledge, 2003), 204–214.

On the Origins of Music[edit]

- Laurel J. Trainor, "The origins of music in auditory scene analysis and the roles of evolution and culture in musical creation," in Biology, Cognition and Origins of Musicality, one of twelve contributions, published March 19, 2015. Presents hypotheses about how adaptive, exaptive and cultural processes may have been involved in some aspects of musical emergence.

Music Bibliography[edit]

Davies, Stephen. “Non-Western Art and Art’s Definition” in Theories of Art Today, 2000.

Dean, J. “The Nature of Concepts and the Definition of Art,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 61, 2003, 29-35.

Hamilton, Andy. Aesthetics and Music, New York: Continuum, 2007.

Margolis, E. and Laurence, S. “Concepts,” in E.N. Zalta (ed.) The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Fall 2008 edition. <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2008/entries/concepts/>.

Meskin, A. “From Defining Art to Defining the Individual Arts: The Role of Theory in the Philosophies of Arts,” in K. Stock and K. Thomson-Jones (eds.) New Waves in Aesthetics, New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008, pp. 125-49.

Scruton, Roger. The Aesthetics of Music, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Stevens, C. and Byron, T. “Universals in Music Processing,” in Hallam, Cross, and Thaut 2009, pp. 14-23.

Wallin, N. L., B. Merker, and S. Brown (eds.) The Origins of Music, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000.

Alperson, P., 1984, “On Musical Improvisation”, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 43: 17–29.

–––, 1998, “Improvisation: An Overview.” In Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, M. Kelly (ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press, vol. 1, 478–479.

Aristotle, 1987, "Poetics." Stephen Halliwell (trans.), London: Duckworth.

Bartel, C., 2011, “Music without Metaphysics?”, British Journal of Aesthetics, 51: 383–398.

Bicknell, J., 2005, “Just a Song? Exploring the Aesthetics of Popular Song Performance”, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 63: 261–270.

–––, 2007a, “Reflections on ‘John Henry’: Ethical Issues in Singing Performance”, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 67: 173–180.

–––, 2007b, “Explaining Strong Emotional Responses to Music: Sociality and Intimacy”, Journal of Consciousness Studies, 14: 5–23.

–––, 2009, Why Music Moves Us, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bicknell J. & J.A. Fisher. "Special Issue on Song, Songs, and Singing". Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. Volume 71, Issue 1, February 2013, 1-132.

Brown, L., 1996, “Musical Works, Improvisation, and the Principle of Continuity”, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 54: 353–69.

–––, 2000, “‘Feeling My Way…’: Jazz Improvisation and its Vicissitudes – A Plea for Imperfection”, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 58: 113–23.

–––, 2011, “Do Higher-Order Music Ontologies Rest on a Mistake?”, British Journal of Aesthetics, 51: 169–84.

–––, 2012, “Further Doubts about Higher-Order Ontology: Reply to Andrew Kania”, British Journal of Aesthetics, 52: 103–6.

Budd, M., 1985a, Music and the Emotions: The Philosophical Theories, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

–––, 1985b, “Understanding Music”, Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, supp. vol. 59: 233–48.

–––, 1995, Values of Art: Pictures, Poetry and Music, London: Penguin.

–––, 2003, “Musical Movement and Aesthetic Metaphors”, British Journal of Aesthetics, 43: 209–23.

Cameron, R., 2008, “There Are No Things That Are Musical Works”, British Journal of Aesthetics, 48: 295–314.

Caplan, B. and C. Matheson, 2004, “Can a Musical Work be Created?”, British Journal of Aesthetics, 44: 113–34.

–––, 2006, “Defending Musical Perdurantism”, British Journal of Aesthetics, 46: 59–69.

Carroll, N., 1988, Mystifying Movies: Fads and Fallacies in Contemporary Film Theory, New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Cochrane, T., 2010a, “Music, Emotions and the Influence of the Cognitive Sciences”, Philosophy Compass, 5: 978–88.

–––, 2010b, “A Simulation Theory of Musical Expressivity”, Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 88: 191–207.

Collingwood, R.G., 1938, The Principles of Art, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cooke, D., 1959, The Language of Music, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Currie, Gregory, 1989, An Ontology of Art, New York, NY: St. Martin's Press.

Davies, David, 2004, Art as Performance, Malden, MA: Blackwell.

–––, 2009, “The Primacy of Practice in the Ontology of Art”, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 67: 159–71.

Davies, S., 1987, “The Evaluation of Music”, reprinted in Davies 2003a, pp. 195–212.

–––, 1991, “The Ontology of Musical Works and the Authenticity of their Performances”, reprinted in S. Davies 2003a, pp. 60–77.

–––, 1994, Musical Meaning and Expression, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

–––, 1997a, “John Cage's 4′33″: Is it Music?”, reprinted in 11–29.

–––, 1997b, “Contra the Hypothetical Persona in Music”, reprinted in S. Davies 2003a, 152–68.

–––, 2001, Musical Works and Performances: A Philosophical Exploration, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

–––, 2003, “Ontologies of Musical Works”, in Themes in the Philosophy of Music, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 30–46.

–––, 2006, “Artistic Expression and the Hard Case of Pure Music”, in Contemporary Debates in Aesthetics and the Philosophy of Art, M. Kieran (ed.), Malden, MA: Blackwell, 179–91.

–––, 2008, “Musical Works and Orchestral Colour”, British Journal of Aesthetics, 48: 363–75.

–––, 2011a, “Cross-cultural Musical Expressiveness: Theory and the Empirical Program”, in Musical Understandings and Other Essays on the Philosophy of Music, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 34–46.

–––, 2011b, “Emotional Contagion from Music to Listener”, in Musical Understandings and Other Essays on the Philosophy of Music, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 47–65.

–––, 2011c, “Musical Understandings”, in Musical Understandings and Other Essays on the Philosophy of Music, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 88–129.

–––, 2011d, “Music and Metaphor”, in Musical Understandings and Other Essays on the Philosophy of Music, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 21–34.

DeBellis, M., 1995, Music and Conceptualization, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dewey, J., 1934, Art as Experience, New York, NY: Minton, Balch.

Dodd, J., 2000, “Musical Works as Eternal Types”, British Journal of Aesthetics, 40: 424–40.

–––, 2002, “Defending Musical Platonism”, British Journal of Aesthetics, 42: 380–402.

–––, 2005, “Critical Study: Artworks and Generative Performances”, British Journal of Aesthetics, 45: 69–87.

–––, 2007, Works of Music: An Essay in Ontology, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

–––, 2010, “Confessions of an Unrepentant Timbral Sonicist”, British Journal of Aesthetics, 50: 33–52.

Goehr, L., 1992, The Imaginary Museum of Musical Works: An Essay in the Philosophy of Music, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

–––, 1998, The Quest for Voice: On Music, Politics, and the Limits of Philosophy: The 1997 Ernest Bloch Lectures, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Goldman, A., 1992, “The Value of Music”, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 50: 35–44.

–––, 1995, “Emotions in Music (A Postscript)”, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 53: 59–69.

Goodman, N., 1968. Languages of Art; references are to the second edition (1976). Indianapolis, IN: Hackett.

Gould, C. and K. Keaton, 2000, “The Essential Role of Improvisation in Musical Performance”, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 58: 143–48.

Gracyk, T., 1996, Rhythm and Noise: An Aesthetics of Rock, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

–––, 2001, I Wanna Be Me: Rock Music and the Politics of Identity, Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

–––, 2011, “Evaluating Music”, in Gracyk & Kania 2011, 165–75.

Gracyk, T. & A. Kania (eds.), 2011, ' The Routledge Companion to Philosophy and Music, New York: Routledge.

Hagberg, G., 1998, “Improvisation: Jazz Improvisation”, in Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, M. Kelly (ed.), New York, NY: Oxford University Press, vol. 1, 479–82.

–––, 2002, “On Representing Jazz: An Art Form in Need of Understanding”, Philosophy and Literature, 26: 188–98.

Hamilton, A., 2007, Aesthetics and Music, New York: Continuum.

Hanslick, E., 1986, On the Musically Beautiful: A Contribution towards the Revision of the Aesthetics of Music, G. Payzant (trans.), Indianapolis, IN: Hackett.

Higgins, K. M., 1991, The Music of Our Lives, Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Howell, R., 2002, “Types, Indicated and Initiated”, British Journal of Aesthetics, 42: 105–27.

Hume, D., 1757, “Of Tragedy”, reprinted in Essays: Moral, Political, and Literary, E. Miller (ed.), Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Classics (1985), 216–25.

Huovinen, E., 2008, “Levels and Kinds of Listeners' Musical Understanding”, British Journal of Aesthetics, 48: 315–37.

–––, 2011, “Understanding Music”, in Gracyk & Kania 2011, pp. 123–33.

Ingarden, R., 1986, The Work of Music and the Problem of its Identity, Adam Czerniawski (trans.), Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. (First published in German in 1961.)

Jackendoff, R., 2011, “Music and Language”, in Gracyk & Kania 2011, 101–12.

Kania, A., 2006, “Making Tracks: The Ontology of Rock Music”, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 64: 401–14.

–––, 2008a, “New Waves in Musical Ontology”, in New Waves in Aesthetics, K. Stock and K. Thomson-Jones (eds.), New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 20–40.

–––, 2008b, “Piece for the End of Time: In Defence of Musical Ontology”, British Journal of Aesthetics, 48: 65–79.

–––, 2008c, “The Methodology of Musical Ontology: Descriptivism and Its Implications”, British Journal of Aesthetics, 48: 426–44.

–––, 2010, “Silent Music”, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 68: 343–53.

–––, 2011a, “Definition”, in Gracyk & Kania 2011, 1–13.

–––, 2011b, “All Play and No Work: An Ontology of Jazz”, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 69: 391–403.

–––, 2012, “In Defence of Higher-Order Musical Ontology: A Reply to Lee B. Brown”, British Journal of Aesthetics, 52: 97–102.

–––, forthcoming a, “Music”, in The Routledge Companion to Aesthetics, third edition, D.M. Lopes & B. Gaut (eds.), New York: Routledge.

–––, forthcoming b, “Platonism vs. Nominalism in Contemporary Musical Ontology”, in Art & Abstract Objects, Christy Mag Uidhir (ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 197–219.

Kivy, P., 1980, The Corded Shell: Reflections on Musical Expression, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

–––, 1983a, “Platonism in Music: A Kind of Defense”, reprinted in Kivy 1993, 35–58.

–––, 1983b, “Platonism in Music: Another Kind of Defense”, reprinted in Kivy 1993, 59–74.

–––, 1988a, “Orchestrating Platonism”, reprinted in Kivy 1993, 75–94.

–––, 1988b, Osmin's Rage: Philosophical Reflections on Opera, Drama, and Text, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Second edition (1999) with a new preface and final chapter, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.)

–––, 1989, Sound Sentiment: An Essay on the Musical Emotions, including the complete text of The Corded Shell, Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

–––, 1993, The Fine Art of Repetition: Essays in the Philosophy of Music, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

–––, 1994, “Speech, Song, and the Transparency of Medium: A Note on Operatic Metaphysics”, reprinted in Musical Worlds: New Directions in the Philosophy of Music, P. Alperson (ed.), University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press (1998), 63–68.

–––, 1995, Authenticities: Philosophical Reflections on Musical Performance, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

–––, 1997a, “Music in the Movies: A Philosophical Enquiry”, in Film Theory and Philosophy, R. Allen and M. Smith (eds.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 308–328.

–––, 1997b, Philosophies of Arts: An Essay in Differences, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

–––, 1999, “Feeling the Musical Emotions”, British Journal of Aesthetics, 39: 1–13.

–––, 2001, “Music in Memory and Music in the Moment” in his New Essays on Musical Understanding, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 183–217.

–––, 2002, Introduction to a Philosophy of Music, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

–––, 2006, “Critical Study: Deeper Than Emotion”, British Journal of Aesthetics, 46: 287–311.

Langer, S., 1953, Feeling and Form, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Lerdahl, F. and R. Jackendoff, 1983, A Generative Theory of Tonal Music, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Levinson, J., 1980, “What a Musical Work Is”, reprinted in Levinson 1990a, 63–88.

–––, 1982, “Music and Negative Emotion”, reprinted in Levinson 1990a, 306–35.

–––, 1984, “Hybrid Art Forms”, reprinted in Levinson 1990a, 26–36.

–––, 1987, “Song and Music Drama”, reprinted in Levinson 1996a, 42–59.

–––, 1990a, Music, Art, and Metaphysics, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

–––, 1990b, “The Concept of Music”, in Levinson 1990a, 267–78.

–––, 1990c, “What a Musical Work Is, Again”, in Levinson 1990a, 215–63.

–––, 1990d, “Authentic Performance and Performance Means”, in Levinson 1990a, 393–408.

–––, 1990e, “Musical Literacy”, reprinted in Levinson 1996a, 27–41.

–––, 1990f, “Evaluating Musical Performance”, in Levinson 1990a, 376–92.

–––, 1992, “Pleasure and the Value of Works of Art”, reprinted in Levinson 1996a, 11–24.

–––, 1996a, The Pleasures of Aesthetics, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

–––, 1996b, “Musical Expressiveness”, in Levinson 1996a, 90–125.

–––, 1996c, “Film Music and Narrative Agency”, reprinted in Levinson 2006a, 143–83.

–––, 1997, Music in the Moment, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

–––, 1999, “Reply to commentaries on Music in the Moment”, Music Perception, 16: 485–94.

–––, 2006a, Contemplating Art: Essays in Aesthetics, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

–––, 2006b, “Concatenationism, Architectonicism, and the Appreciation of Music”, Revue Internationale de Philosophie, 60: 505–14.

–––, 2006c, “Musical Expressiveness as Hearability-as-expression”, in Contemporary Debates in Aesthetics and the Philosophy of Art, M. Kieran (ed.), Malden, MA: Blackwell, 192–206.

Matravers, D., 1998, Art and Emotion, Oxford: Clarendon.

–––, 2011, “Arousal Theories”, in Gracyk & Kania 2011, 212–22.

Meyer, L., 1956, Emotion and Meaning in Music, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.