Sp3. Are there any non-black musicians in the pantheon of jazz?

Contents

- 1 Discussion

- 2 Introduction

- 3 The meaning of pantheon

- 4 Implications for the pantheon of jazz musicians

- 5 Rankings of non-black musicians

- 6 Conclusions about non-black jazz musicians being in the pantheon 🏛 of jazz

- 7 Top 100 Jazz artists ranked from list of AcclaimedMusic.net's "Top (Musical) Artists of All Time" out of 4112

- 8 Significant non-black jazz instrumental musicians

- 9 NOTES

Discussion[edit]

Introduction[edit]

Wynton Marsalis (b. 1961) claims that there are no white players in the pantheon of jazz: “Do I have a problem saying there are no white players in the pantheon of jazz? No. There’s Bird, Louis, Trane, Duke, Monk and Miles. Now let’s look at classical composers—Beethoven, Brahms, Bartók, Mozart. I can name all of them and never name a Negro. Is that a problem? No.”[1] (no bold italic in original)

If the pantheon of jazz only includes the musicians Marsalis mentions, then none of those players were other than black so Marsalis would be correct.

The meaning of pantheon[edit]

➢ What does "pantheon mean anyway?

Dictionary.com gives these relevant definitions for the meaning of pantheon:

-

“3. the place of the heroes or idols of any group, individual, movement, party, etc., or the heroes or idols themselves.”

“3. the place of the heroes or idols of any group, individual, movement, party, etc., or the heroes or idols themselves.”

-

“4. a temple dedicated to all the gods.”

“4. a temple dedicated to all the gods.”

-

“5. the gods of a particular mythology considered collectively.”

“5. the gods of a particular mythology considered collectively.”

- The origin of the word is from around 1375–1425 A.D. from late Middle English using the Latin word "panteon" from the Greek word "Panthēon" with "Pántheion," the noun use of the neuter of "pántheios" meaning "of all gods."

Merriam Webster Dictionary relevant definitions for pantheon:

Other dictionaries use these definitions for pantheon:

(Photograph of a Mexican peacock 🦚 glass sculpture at the Museum of Popular Art in Mexico City)

(Graphic uses a bronzing filter with added PoJ.fm logos and a saxophone)

Implications for the pantheon of jazz musicians[edit]

Because the musicians that could be chosen to be in a jazz pantheon could theoretically be of any size, there is no upper limit for a jazz pantheon's size other than constrained by the entire size of the total number of past jazz musicians.

➢ What is the total current number of jazz musicians that have ever been on planet Earth 🌎?

➢ How should anyone determine the greatest jazz players?

There may possibly be little known great jazz players, especially amongst women in jazz. Of the established jazz musicians, one can start to sort them out by which ones contributed the most and had the largest effect on other players and the field of jazz itself. That list could be something like the following chosen from the most well known players. Vocalists get their own rankings.

Rankings of non-black musicians[edit]

- (NB1)

See Charles Waring's lists ranking jazz musicians: "The 50 Best Jazz Singers Of All Time" at UDiscoverMusic.com, published May 17, 2021, “including loud, robust voices to delicate, refined ones, from vocal gymnasts to ultra smooth balladeers.” As seen in the table below, there are 15 non-black jazz vocalists out of the top fifty (30%).

See Charles Waring's lists ranking jazz musicians: "The 50 Best Jazz Singers Of All Time" at UDiscoverMusic.com, published May 17, 2021, “including loud, robust voices to delicate, refined ones, from vocal gymnasts to ultra smooth balladeers.” As seen in the table below, there are 15 non-black jazz vocalists out of the top fifty (30%).

| Ranking of Non-black Jazz Vocalists from UDiscoverMusic.com's "50 Best All Time Vocalists" | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

- (NB2)

"The 25 Best Female Jazz Singers Of All Time," published March 12, 2021. Ten out of twenty-five (40%) are not black.

"The 25 Best Female Jazz Singers Of All Time," published March 12, 2021. Ten out of twenty-five (40%) are not black.

- (NB3)

"The 50 Best Jazz Drummers Of All Time" “from big-band leaders to bebop pioneers and fusion futurists, published on July 15, 2021.” Twelve of the fifty best jazz drummers (24%) are not black, including two in the top ten (20%) (Buddy Rich #7 & Gene Krupa #8).

"The 50 Best Jazz Drummers Of All Time" “from big-band leaders to bebop pioneers and fusion futurists, published on July 15, 2021.” Twelve of the fifty best jazz drummers (24%) are not black, including two in the top ten (20%) (Buddy Rich #7 & Gene Krupa #8).

- (NB4)

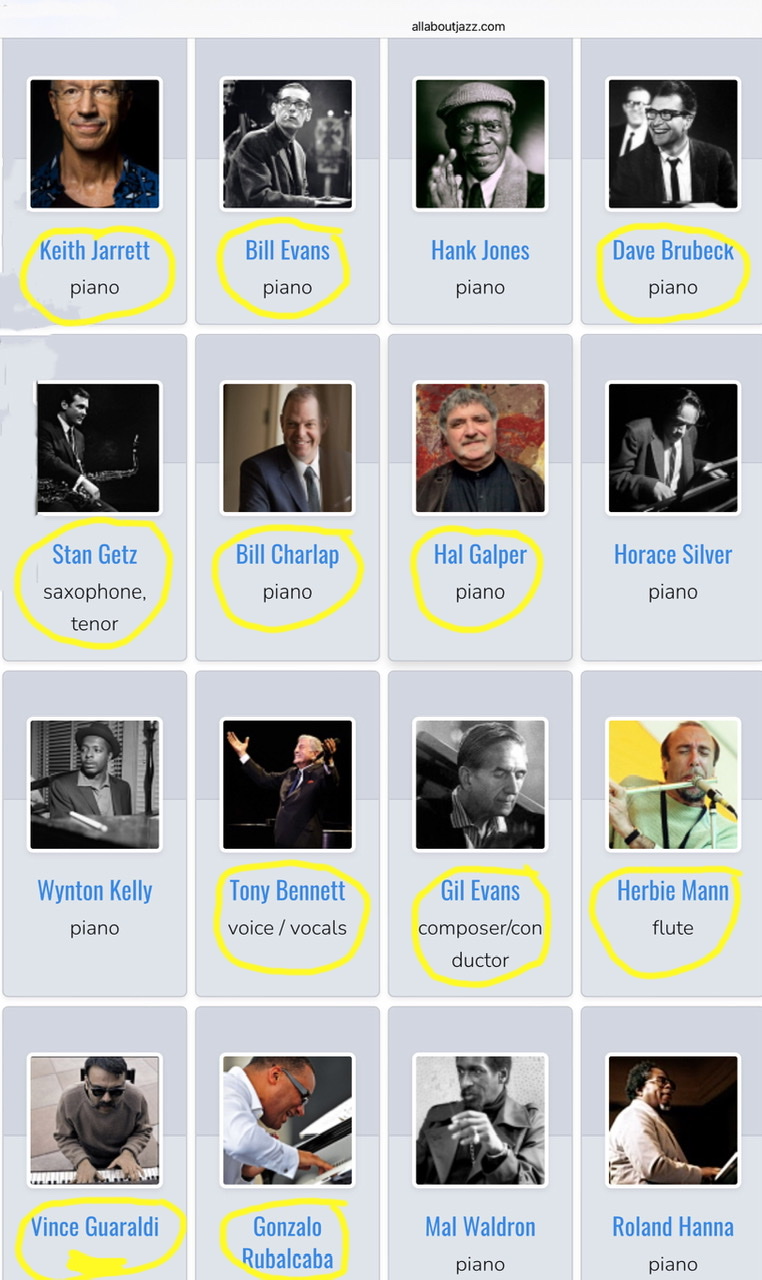

"The 50 Best Jazz Pianists Of All Time," “includes iconic bandleaders to unique talents who have shaped the jazz genre and revolutionized the role of the piano in music,” published February 16, 2021. Twelve out of fifty (24%) are non-black players, with three in the top ten (30%): (Bill Evans #3, Keith Jarrett #8, Chick Corea, #9), five in top twenty (Jelly Roll Morton #15, Dave Brubeck #16), eight in the top twenty-five (Joe Zawinul #22, George Shearing #23, Bob James, #24).

"The 50 Best Jazz Pianists Of All Time," “includes iconic bandleaders to unique talents who have shaped the jazz genre and revolutionized the role of the piano in music,” published February 16, 2021. Twelve out of fifty (24%) are non-black players, with three in the top ten (30%): (Bill Evans #3, Keith Jarrett #8, Chick Corea, #9), five in top twenty (Jelly Roll Morton #15, Dave Brubeck #16), eight in the top twenty-five (Joe Zawinul #22, George Shearing #23, Bob James, #24).

- (NB5)

"The 50 Best Jazz Trumpeters Of All Time," published on June 15, 2021. Eleven out of fifty (22%) are non-black: (Chet Baker #7), (Bix Beiderbecke # 17), (Don Ellis #19), (Maynard Ferguson #21), (Tomasz Stanko #36), (Dave Douglas #38), (Arturo Sandoval #40), (Randy Brecker #46), (Mugsy Spanier #47), (Arve Henriksen #48), (Erik Truffaz #49).

"The 50 Best Jazz Trumpeters Of All Time," published on June 15, 2021. Eleven out of fifty (22%) are non-black: (Chet Baker #7), (Bix Beiderbecke # 17), (Don Ellis #19), (Maynard Ferguson #21), (Tomasz Stanko #36), (Dave Douglas #38), (Arturo Sandoval #40), (Randy Brecker #46), (Mugsy Spanier #47), (Arve Henriksen #48), (Erik Truffaz #49).

- (NB6)

"The 50 Best Jazz Saxophonists Of All Time," published on September 13, 2021. Fourteen out of fifty (28%) are non-black with two out of the top ten (20%) in Stan Getz #4 and Art Pepper #8:

"The 50 Best Jazz Saxophonists Of All Time," published on September 13, 2021. Fourteen out of fifty (28%) are non-black with two out of the top ten (20%) in Stan Getz #4 and Art Pepper #8:

| Ranking of Non-black Saxophonists from UDiscoverMusic.com's "50 Best Jazz Saxophonists" | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

- (NB7)

"The 50 Best Jazz Bassists of All Time," “including those who elevated the instrument from a mere time-keeping role to versatile pathfinders and visionary composers,” published on August 20, 2021. Eighteen out of fifty (36%) are non-black with two in the top ten (20%) (Jaco Pastorius #1, Charlie Haden #9).

"The 50 Best Jazz Bassists of All Time," “including those who elevated the instrument from a mere time-keeping role to versatile pathfinders and visionary composers,” published on August 20, 2021. Eighteen out of fifty (36%) are non-black with two in the top ten (20%) (Jaco Pastorius #1, Charlie Haden #9).

| Ranking of Non-black Jazz Bassists from UDiscoverMusic.com's 50 Best Jazz Bassists | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

- (NB8)

Fidlarmusic.com ranks "The 20 Best Jazz Bassists of All Time" circled in yellow in table

Fidlarmusic.com ranks "The 20 Best Jazz Bassists of All Time" circled in yellow in table  with five non-blacks in the top ten (50%) and an overall percentage of 40%: Jaco Pastorius #3, Bill Black (played with Elvis) #7, Scott LaFaro #8, Charlie Haden #9, Dave Holland #10, John Patitucci #13, George Mraz #15, and Eberhard Weber #17.

with five non-blacks in the top ten (50%) and an overall percentage of 40%: Jaco Pastorius #3, Bill Black (played with Elvis) #7, Scott LaFaro #8, Charlie Haden #9, Dave Holland #10, John Patitucci #13, George Mraz #15, and Eberhard Weber #17.

- (NB9)

Matt Fripp at JazzFuel.com ranks the top ten jazz musicians of all time with Chet Baker #9 being the only non-black musician (10%):

Matt Fripp at JazzFuel.com ranks the top ten jazz musicians of all time with Chet Baker #9 being the only non-black musician (10%):

- Miles Davis

- Louis Armstrong

- John Coltrane

- Charles Mingus

- Thelonious Monk

- Ella Fitzgerald

- Charlie Parker

- Duke Ellington

- Chet Baker

- Ornette Coleman

- (NB10)

Matt Fripp at JazzFuel.com lists but does not rank order "The Best Jazz Musicians of All Time – 40 Legendary Jazz Artists"," September 18, 2020. There are nine out of forty non-blacks (22.5%).

Matt Fripp at JazzFuel.com lists but does not rank order "The Best Jazz Musicians of All Time – 40 Legendary Jazz Artists"," September 18, 2020. There are nine out of forty non-blacks (22.5%).

| List (unranked) of Non-black musicians from Matt Fripp's "Best Jazz Musicians of All Time from 40 Legends" |

|---|

|

|

- (NB11)

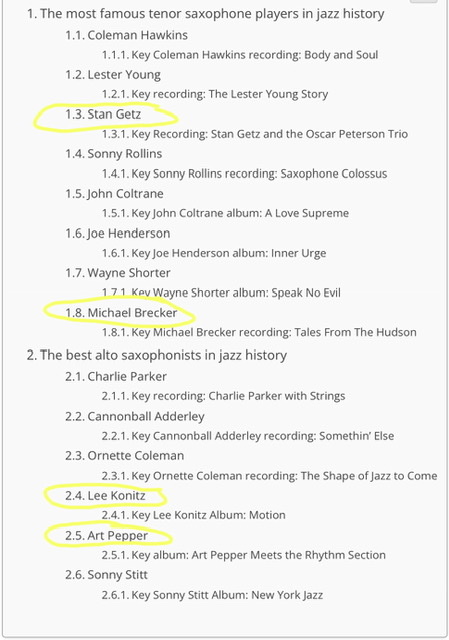

JazzFuel.com ranks "The Best Jazz Saxophone Players In History (Jazz Legends)," from August 25, 2020 with two out of eight tenor players (25%) and two out of six alto players (33%) being non-black and circled in yellow in the table below for a total of four out of fourteen (28.6%)

JazzFuel.com ranks "The Best Jazz Saxophone Players In History (Jazz Legends)," from August 25, 2020 with two out of eight tenor players (25%) and two out of six alto players (33%) being non-black and circled in yellow in the table below for a total of four out of fourteen (28.6%)

- (NB12)

Matt Fripp's "The 50 Best Jazz Albums of All Time (Essential Listening Guide)," from JazzFuel.com, May 5, 2020 with thirteen out of fifty by a leader who is non-black (26%).

Matt Fripp's "The 50 Best Jazz Albums of All Time (Essential Listening Guide)," from JazzFuel.com, May 5, 2020 with thirteen out of fifty by a leader who is non-black (26%).

| Ranking on Matt Fripp's "50 Best Jazz Albums of All Time (Essential Listening Guide)" by non-black leaders |

|---|

|

|

Conclusions about non-black jazz musicians being in the pantheon 🏛 of jazz[edit]

There is no doubt amongst all informed experts that Afro-Americans were the race most involved with more groundbreaking jazz performances and recordings throughout its history. Nevertheless, other races could and did make significant contributions through all of jazz's history.

To get a rough approximation as to the percentage of non-black jazz musicians in the jazz pantheon one can take an average from the combined percentages determined above from all of the (NB) 1–12 percentages.

- (NB1) 30% — 50 best jazz singers

- (NB2) 40% — 25 best female jazz singers

- (NB3) 24% — 50 best jazz drummers

- (NB4) 24% — 50 best jazz pianists

- (NB5) 22% — 50 best jazz trumpeters

- (NB6) 28% — 50 best jazz saxophonists

- (NB7) 36% — 50 best jazz bassists

- (NB8) 40% — 20 best jazz bassists

- (NB9) 10% — Top 10 jazz musicians

- (NB10) 22.5% — 40 best jazz musicians

- (NB11) 28.6% — 18 best saxophonists

- (NB12) 26% — 50 best jazz albums

CONCLUSION: The total of (NBs) is 331.1 divided by twelve gives 27.6% non-blacks are in the pantheon of jazz music.

Lawrence Gushee (1931–2015) reports on a possibly surprising fact regarding the relative percentages of (male) musicians proportioned by race in early jazz history in the four cities of Chicago, New York, Los Angeles, and New Orleans. The possibly surprising fact is that black musicians were in the minority of those reported in 1910 and 1920 censuses from those four major cities.

“In making comparisons between such urban centers as Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles, one must bear in mind that the ethnic distribution of the population, as well as the patterns of internal immigration were very different from one locale to the other. In Chicago in 1910 there were 3,241 male musicians and music teachers, 136 of whom were Negroes; while in Los Angeles the census takers recorded only 9 Negro musicians out of a total of 590. (For comparison's sake, out of 372 musicians in New Orleans, 112 were black.) A decade later, there were 254 black musicians in Chicago (in a total of 3,415) and 48 in Los Angeles (in a total of 1,146), while in New Orleans the number of black male musicians had dropped: 86 out of 354.2

It should also be kept in mind that the census occupational statistics for large cities on the West Coast show that Los Angeles was by far the most receptive and San Francisco the least, to the point of having the smallest proportion of black musicians of any major U.S. city. While this may be due in part to the choice of Oakland as a place of residence by many musicians working in San Francisco, the combining of the two cities doesn't alter the rank order.”“Footnote 2. In the early part of this century, female musicians and music teachers have not been included; the great majority of them were probably part-time music teachers. Unfortunately, the published tabulations for the various censuses do not permit the correlation of place of both, residence at the time of the census, and the occupation of musician or music teacher.”[2] (bold not in original)

At UDiscoverMusic.com's "The Greatest Jazz Guitarists lists whom they consider the top 75 jazz guitar albums of all-time. More than half of the guitarists are non-black.

Top 100 Jazz artists ranked from list of AcclaimedMusic.net's "Top (Musical) Artists of All Time" out of 4112[edit]

In the listing, there are plenty more jazz musicians/groups after #1335. In the table, there are 40 non-black musicians/groups listed (40%). Mose Allison (1927–2016) (#3884.) is the last jazz musician on the list out of 4,112.

![]() AcclaimedMusic.net's "Top Jazz Albums of All Time" has approximately 17% non-black leader albums.

AcclaimedMusic.net's "Top Jazz Albums of All Time" has approximately 17% non-black leader albums.

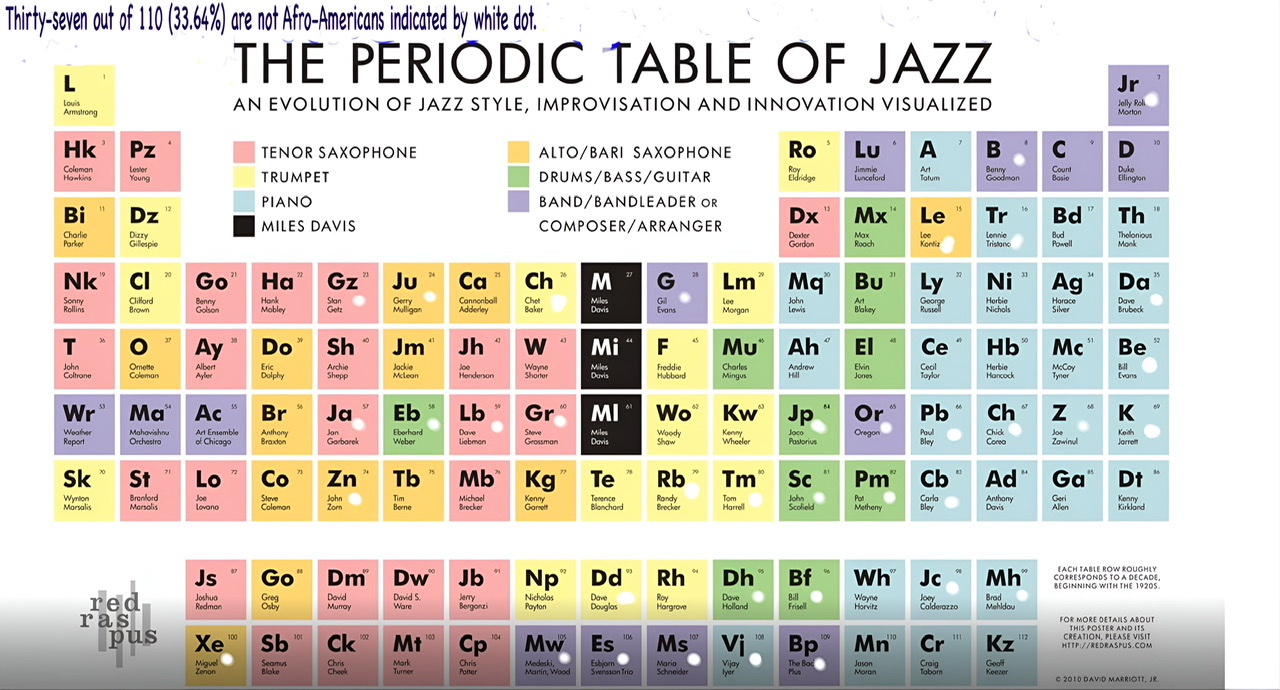

![]() The Jazzomat Research Project

The Jazzomat Research Project  at the Weimar Jazz Database

at the Weimar Jazz Database  contains 78 jazz musicians solos and 24 of the musicians are not of the Afro-American race making up 30.77% of the total.

contains 78 jazz musicians solos and 24 of the musicians are not of the Afro-American race making up 30.77% of the total.

(Photograph of a Mexican peacock glass sculpture at the Museum of Popular Art in Mexico City with PoJ.fm logos and a saxophone added)

Significant non-black jazz instrumental musicians[edit]

-

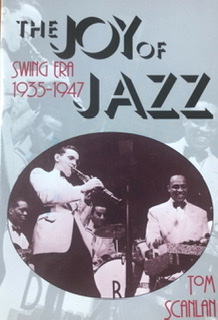

A longtime jazz columnist for The Army Times and editor at The Federal Times, reviewer Tom Scanlan, co-author of Rhythm Man (1991)

A longtime jazz columnist for The Army Times and editor at The Federal Times, reviewer Tom Scanlan, co-author of Rhythm Man (1991)  and The Joy of Jazz: Swing Era, 1935–1947 (1996)

and The Joy of Jazz: Swing Era, 1935–1947 (1996)  , finds some of Whitney Balliett's observations about the paucity of non-black jazz musicians to be 'absurd ignorant nonsense.'

, finds some of Whitney Balliett's observations about the paucity of non-black jazz musicians to be 'absurd ignorant nonsense.'

“Anyone deeply interested in jazz music will be apt to question many of Balliett's easy generalizations. Thus praise for his work must be limited. . . . But though much of Balliett's commentary is exceptionally able, some of it strikes this reviewer as ignorant nonsense. For example, there is this startling opinion from Balliett: "There have been dozens of first-rate Negro musicians and, give or take a Gerry Mulligan or Stan Getz, only five comparable white musicians: Bix Beiderbecke, Dave Tough, Pee Wee Russell, Jack Teagarden, and Django Reinhardt." Granted that most all of the finest jazz musicians have been Negro, that paragraph by Balliett is absurd. What kind of nutty Crow-Jim thinking is this and where does it leave such great jazz musicians as Benny Goodman, Bunny Berigan, Bud Freeman, Red Norvo and Billy Butterfield? Is Mr. Balliett suggesting that there have been dozens of Negro musicians superior to Goodman? That's nonsense.”[3] (bold and bold italic not in original)

-

Jelly Roll Morton (1890–1941)

Jelly Roll Morton (1890–1941) -

an American pianist, singer, bandleader, composer, arranger who played stomps, rags, show pieces, and was a pivotal figure in early jazz. Morton was of Creole heritage and did not consider himself to be an Afro-American.

an American pianist, singer, bandleader, composer, arranger who played stomps, rags, show pieces, and was a pivotal figure in early jazz. Morton was of Creole heritage and did not consider himself to be an Afro-American.

-

-

Bix Beiderbecke (1903–1931)

Bix Beiderbecke (1903–1931) -

Bix Beiderbecke was born white in Iowa. He was one of the most popular and sophisticated jazz cornet players of the Roaring Twenties. His smooth sound was especially popular on college campuses. Beiderbecke was sent to school in Chicago, but ended up becoming immersed in the jazz culture of the city. He joined the Wolverines jazz band and made his first recording in 1924. Beiderbecke then played with Frankie Trumbauer's band in St. Louis. In 1926, Bix joined the Jean Goldkette Orchestra and the radio broadcasts brought Beiderbecke national praise. All of the major players in the Goldkette band were white.

Bix Beiderbecke was born white in Iowa. He was one of the most popular and sophisticated jazz cornet players of the Roaring Twenties. His smooth sound was especially popular on college campuses. Beiderbecke was sent to school in Chicago, but ended up becoming immersed in the jazz culture of the city. He joined the Wolverines jazz band and made his first recording in 1924. Beiderbecke then played with Frankie Trumbauer's band in St. Louis. In 1926, Bix joined the Jean Goldkette Orchestra and the radio broadcasts brought Beiderbecke national praise. All of the major players in the Goldkette band were white.

-

-

Wikipedia: Jean Goldkette reports that Goldkette's band even beat Fletcher Henderson's (1897–1952) orchestra in a grand ‘battle of the bands’ at the Roseland Theater in New York in 1927: “The head arranger [of Goldkette's orchestra] was Bill Challis and the musicians included Bix Beiderbecke, Steve Brown, Hoagy Carmichael, Jimmy Dorsey, Tommy Dorsey, Eddie Lang, Chauncey Morehouse, Don Murray, Bill Rank, and Spiegle Willcox. Afro-American cornetist, Rex Stewart (1907–1967), a member of the rival Fletcher Henderson's band, wrote that "[Goldkette's Orchestra] was, without any question, the greatest in the world . . . the original predecessor to any large white dance orchestra that followed, up to Benny Goodman." English jazz discographer Brian Rust (1922–2011) also called it "the greatest band of them all."” In 1927, Biederbecke joined the Paul Whiteman (1890–1967) orchestra where his polished sound and precise rhythms melded well with the Whiteman orchestra's symphonic sound.

Wikipedia: Jean Goldkette reports that Goldkette's band even beat Fletcher Henderson's (1897–1952) orchestra in a grand ‘battle of the bands’ at the Roseland Theater in New York in 1927: “The head arranger [of Goldkette's orchestra] was Bill Challis and the musicians included Bix Beiderbecke, Steve Brown, Hoagy Carmichael, Jimmy Dorsey, Tommy Dorsey, Eddie Lang, Chauncey Morehouse, Don Murray, Bill Rank, and Spiegle Willcox. Afro-American cornetist, Rex Stewart (1907–1967), a member of the rival Fletcher Henderson's band, wrote that "[Goldkette's Orchestra] was, without any question, the greatest in the world . . . the original predecessor to any large white dance orchestra that followed, up to Benny Goodman." English jazz discographer Brian Rust (1922–2011) also called it "the greatest band of them all."” In 1927, Biederbecke joined the Paul Whiteman (1890–1967) orchestra where his polished sound and precise rhythms melded well with the Whiteman orchestra's symphonic sound.

-

-

Austin High Gang (1901–1902)

Austin High Gang (1901–1902)-

began playing at the Friar's Inn in Chicago consisting of all white musicians including Frank Teschemacher (clarinet), Jimmy McPartland (cornet), Richard "Dick" McPartland (guitar and banjo) and Lawrence "Bud" Freeman (sax). Others such as Gene Krupa (drums) joined them later.

began playing at the Friar's Inn in Chicago consisting of all white musicians including Frank Teschemacher (clarinet), Jimmy McPartland (cornet), Richard "Dick" McPartland (guitar and banjo) and Lawrence "Bud" Freeman (sax). Others such as Gene Krupa (drums) joined them later.

-

-

Paul Whiteman (1890–1967)

Paul Whiteman (1890–1967)-

known as the "King of (symphonic) Jazz" in the 1920s in the United States 🇺🇸. Whiteman gained fame for the musicians that he employed, such as: Bing Crosby, Bix Beiderbecke, Tommy Dorsey, Johnny Mercer, and many more. An important contributions of Whiteman's was commissioning George Gershwin to compose "Rhapsody in Blue" first performed in New York in 1924. Whiteman's band recorded their own best selling composition, "Whispering," in the early 1920s. Although Whiteman's band was quite popular during the 1920s, he cannot be considered a true jazz musician since his band performed mostly popular dance and symphonic music and didn't try to incorporate much improvisation.

known as the "King of (symphonic) Jazz" in the 1920s in the United States 🇺🇸. Whiteman gained fame for the musicians that he employed, such as: Bing Crosby, Bix Beiderbecke, Tommy Dorsey, Johnny Mercer, and many more. An important contributions of Whiteman's was commissioning George Gershwin to compose "Rhapsody in Blue" first performed in New York in 1924. Whiteman's band recorded their own best selling composition, "Whispering," in the early 1920s. Although Whiteman's band was quite popular during the 1920s, he cannot be considered a true jazz musician since his band performed mostly popular dance and symphonic music and didn't try to incorporate much improvisation.

-

-

Benny Goodman (1909–1986)

Benny Goodman (1909–1986)-

Caucasian, the ninth of twelve children born to poor Jewish emigrants from the Russian Empire. His father, David Goodman (1873–1926), came to the United States 🇺🇸 in 1892 from Warsaw in partitioned Poland 🇵🇱 and his mother, Dora Grisinsky, (1873–1964), came from Kaunas, Lithuania 🇱🇹. Benny Goodman was known as the "King of Swing."

Caucasian, the ninth of twelve children born to poor Jewish emigrants from the Russian Empire. His father, David Goodman (1873–1926), came to the United States 🇺🇸 in 1892 from Warsaw in partitioned Poland 🇵🇱 and his mother, Dora Grisinsky, (1873–1964), came from Kaunas, Lithuania 🇱🇹. Benny Goodman was known as the "King of Swing."

-

-

“Who could have guessed that a clarinet player could be the king of anything? Benny Goodman enjoyed a remarkable career as an ambassador of music — the benevolent "King of Swing" — and he introduced jazz to millions of people who loved to dance. Goodman popularized the music of a talented writer and arranger, Fletcher Henderson, and he integrated his band while the rest of America was still yoked to segregation. Frankly, the music deserved the best, and Goodman's units delivered with hairsplitting precision. In "I'm a Ding Dong Daddy (from Dumas)," Goodman's quartet with pianist Teddy Wilson, drummer Gene Krupa and the irrepressible jazz vibraphone master Lionel Hampton (also turning 100 in 2009) makes an inspiring sound.”[4] (bold not in original)

“Who could have guessed that a clarinet player could be the king of anything? Benny Goodman enjoyed a remarkable career as an ambassador of music — the benevolent "King of Swing" — and he introduced jazz to millions of people who loved to dance. Goodman popularized the music of a talented writer and arranger, Fletcher Henderson, and he integrated his band while the rest of America was still yoked to segregation. Frankly, the music deserved the best, and Goodman's units delivered with hairsplitting precision. In "I'm a Ding Dong Daddy (from Dumas)," Goodman's quartet with pianist Teddy Wilson, drummer Gene Krupa and the irrepressible jazz vibraphone master Lionel Hampton (also turning 100 in 2009) makes an inspiring sound.”[4] (bold not in original)

-

It is reported by Gene Anderson in "The Genesis of King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band," American Music, Vol. 12, No. 3 (Autumn, 1994), 283–303 (21 pages), published by University of Illinois Press, at footnote 69. that Warren "Baby" Dodds (1898–1959) reports the following white musicians came to see King Oliver's Creole Orchestra in 1921–1922. “Footnote 69. White musicians named by Baby Dodds include Benny Goodman, Frank Teschemacher, Dave Tough, Bud Freeman, Ben Pollack, along with Paul Whiteman's entire orchestra (Warren "Baby" Dodds, Baby Dodds Story, 37–38).”

It is reported by Gene Anderson in "The Genesis of King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band," American Music, Vol. 12, No. 3 (Autumn, 1994), 283–303 (21 pages), published by University of Illinois Press, at footnote 69. that Warren "Baby" Dodds (1898–1959) reports the following white musicians came to see King Oliver's Creole Orchestra in 1921–1922. “Footnote 69. White musicians named by Baby Dodds include Benny Goodman, Frank Teschemacher, Dave Tough, Bud Freeman, Ben Pollack, along with Paul Whiteman's entire orchestra (Warren "Baby" Dodds, Baby Dodds Story, 37–38).”

-

Louis Prima (1910–1978)

Louis Prima (1910–1978)

-

Charlie Mariano (1923–2009)

Charlie Mariano (1923–2009)

-

Bill Evans (1929–1980)

Bill Evans (1929–1980)-

See wonderful photographs of the pianist taken by Italian master photographer Paolo Ferraresi.

See wonderful photographs of the pianist taken by Italian master photographer Paolo Ferraresi.

-

-

Evans's second album featured written-out endorsements from Miles Davis, George Shearing, Ahmad Jamal, and Cannonball Adderley titled

Evans's second album featured written-out endorsements from Miles Davis, George Shearing, Ahmad Jamal, and Cannonball Adderley titled  "Everybody Digs Bill Evans."

"Everybody Digs Bill Evans."

-

- ☞ Read reviews of the album by Samuel Chell and Michael G. Nastos.

- 🔘 Listen to samples at AllMusic.com.

-

Toshiko Akiyoshi (b. 1929)

Toshiko Akiyoshi (b. 1929)-

Japanese-American conductor and pianist. NEA Jazz master (2007).

Japanese-American conductor and pianist. NEA Jazz master (2007).

-

-

Japanese Free Jazz and Jazz musicians (1969)

Japanese Free Jazz and Jazz musicians (1969) -

As reported at Wikipedia:Japanese jazz: “1969 was a pivotal year for Japanese free jazz, with musicians such as percussionist and composer Masahiko Togashi (1940–2007), guitarist Masayuki Takayanagi (1932–1991), pianists Yosuke Yamashita (b. 1942) and Masahiko Satoh (b. 1941), saxophonist Kaoru Abe (1949–1978), bassist Motoharu Yoshizawa (1931–1998), and trumpeter Itaru Oki (1941–2020) playing a major role.”

As reported at Wikipedia:Japanese jazz: “1969 was a pivotal year for Japanese free jazz, with musicians such as percussionist and composer Masahiko Togashi (1940–2007), guitarist Masayuki Takayanagi (1932–1991), pianists Yosuke Yamashita (b. 1942) and Masahiko Satoh (b. 1941), saxophonist Kaoru Abe (1949–1978), bassist Motoharu Yoshizawa (1931–1998), and trumpeter Itaru Oki (1941–2020) playing a major role.”

-

-

As reported at Wikipedia:Japanese jazz: “Other Japanese jazz artists who acquired international reputations include Sadao Watanabe (b. 1933) (the former soloist of Akiyoshi's Cozy Quartet), fusion guitarist and digital pioneer Ryo Kawasaki (1947–2020), bassist and record producer Teruo Nakamura (b. 1942), jazz fusion trumpeter Toru "Tiger" Okoshi (b. 1950), and pianist Makoto Ozone (b. 1961).”

As reported at Wikipedia:Japanese jazz: “Other Japanese jazz artists who acquired international reputations include Sadao Watanabe (b. 1933) (the former soloist of Akiyoshi's Cozy Quartet), fusion guitarist and digital pioneer Ryo Kawasaki (1947–2020), bassist and record producer Teruo Nakamura (b. 1942), jazz fusion trumpeter Toru "Tiger" Okoshi (b. 1950), and pianist Makoto Ozone (b. 1961).”

-

-

Enrico Rava (b. 1933)

Enrico Rava (b. 1933)

-

Known as the ‘Grandmaster of Italian jazz’ because he first was in Gato Barbieri's Italian quintet in the mid-1960s, next with Steve Lacy's band around 1965–66, moved to New York in 1967 and over the 1970s and 1980s played with:

Known as the ‘Grandmaster of Italian jazz’ because he first was in Gato Barbieri's Italian quintet in the mid-1960s, next with Steve Lacy's band around 1965–66, moved to New York in 1967 and over the 1970s and 1980s played with:

- 🔘 Listen to samples of Enrico Rava – "Easy Living"

(2003).

(2003).

- 🔘 Listen to samples of Enrico Rava – "Easy Living"

- 🔘 Read Christopher Porter's review of Rava's life and career, "Enrico Rava: Easy Living," JazzTimes, updated May 9, 2019. Accessed April 15, 2022.

- 🔘 Read Christopher Porter's review of Rava's life and career, "Enrico Rava: Easy Living," JazzTimes, updated May 9, 2019. Accessed April 15, 2022.

-

JazzTimes reviewer Christopher Porter calls him "Italy’s greatest jazz musician" (2019).

JazzTimes reviewer Christopher Porter calls him "Italy’s greatest jazz musician" (2019).

-

-

Charlie Haden (1937–2014)

Charlie Haden (1937–2014)

-

Chick Corea (1941–2021)

Chick Corea (1941–2021)-

an American jazz composer, keyboardist, bandleader, and occasional percussionist of southern Italian descent, his father having been born to an immigrant from Albi comune, in the Province of Catanzaro in the Calabria region.

an American jazz composer, keyboardist, bandleader, and occasional percussionist of southern Italian descent, his father having been born to an immigrant from Albi comune, in the Province of Catanzaro in the Calabria region.

-

-

Terumasa Hino (b. 1942)

Terumasa Hino (b. 1942)

-

Keith Jarrett (b. 1945)

-

American jazz and classical music pianist and composer of Scots‐Irish and Hungarian descent, or of Slovenian and German descent, according to Wikipedia. Wikipedia: Keith Jarrett reports that he was “born in Allentown, Pennsylvania, United States, to a mother of Slovenian descent. Jarrett's grandmother was born in Segovci, near Apače in Slovenia, (at the time, this was in the Austria of the Austro-Hungarian Empire). Her own parents probably descended from the Slavic population of Prekmurje, a few miles away in a Hungarian part of the Empire almost totally populated by Slovenes. Jarrett's father was of mostly German descent.”

American jazz and classical music pianist and composer of Scots‐Irish and Hungarian descent, or of Slovenian and German descent, according to Wikipedia. Wikipedia: Keith Jarrett reports that he was “born in Allentown, Pennsylvania, United States, to a mother of Slovenian descent. Jarrett's grandmother was born in Segovci, near Apače in Slovenia, (at the time, this was in the Austria of the Austro-Hungarian Empire). Her own parents probably descended from the Slavic population of Prekmurje, a few miles away in a Hungarian part of the Empire almost totally populated by Slovenes. Jarrett's father was of mostly German descent.”

-

-

Jan Garbarek (b. 1947)

Jan Garbarek (b. 1947)-

Norwegian saxophonist recorded with Manfred Eicher’s ECM Records since 1970. Plays a sharp-edged soprano saxophone with Keith Jarrett's 'European Quartet' on Jarrett's "My Song" (1977) with the “pianist’s touching, folky melodies and memorable themes.”

Norwegian saxophonist recorded with Manfred Eicher’s ECM Records since 1970. Plays a sharp-edged soprano saxophone with Keith Jarrett's 'European Quartet' on Jarrett's "My Song" (1977) with the “pianist’s touching, folky melodies and memorable themes.”

-

-

Makoto Ozone (b. 1961)

Makoto Ozone (b. 1961)-

Japanese jazz pianist. Graduated Berklee College of music (1983); recorded with Gary Burton (b. 1943); received honorary doctorate in music from Berklee College of Music (2007).

Japanese jazz pianist. Graduated Berklee College of music (1983); recorded with Gary Burton (b. 1943); received honorary doctorate in music from Berklee College of Music (2007).

-

-

Chris Botti (b. 1962)

Chris Botti (b. 1962)

-

Jazz pianist Hiromi Uehara (b. 1979)

Jazz pianist Hiromi Uehara (b. 1979)-

received worldwide recognition with her debut album "Another Mind"

received worldwide recognition with her debut album "Another Mind"  (2003), the critics admired the album in North America and in Japan, where it went gold by shipping over 100,000 units. The album received the Recording Industry Association of Japan’s (RIAJ) Jazz Album of the Year Award. In 2009, Hiromi performed duets with pianist Chick Corea on "Duet," a two-disc live recording of their duo concert in Tokyo. She also appeared on bassist Stanley Clarke’s "Jazz in the Garden" featuring a former Chick Corea bandmate, drummer Lenny White.

(2003), the critics admired the album in North America and in Japan, where it went gold by shipping over 100,000 units. The album received the Recording Industry Association of Japan’s (RIAJ) Jazz Album of the Year Award. In 2009, Hiromi performed duets with pianist Chick Corea on "Duet," a two-disc live recording of their duo concert in Tokyo. She also appeared on bassist Stanley Clarke’s "Jazz in the Garden" featuring a former Chick Corea bandmate, drummer Lenny White.

-

In the book, Jazz in Black and White: Race, Culture, and Identity in the Jazz Community, author Charles D. Gerard posed the question, “Is jazz a universal idiom or a black art form?” He also writes that white musicians have been a part of jazz since 1910, but “a series of African-American artists have forged the history of jazz—and the developments have been a result of black people’s search for a meaningful identity as Americans and members of the African diaspora.”

“[Jazz] is the one place that doesn’t promote exclusion. “[In jazz] the African spirit is of inclusiveness and unity,” said Keenyn.”[5]

Wikipedia: Jazz Accordionists lists nineteen musicians from around the world born from 1904 to 1964, including one woman. None of the jazz accordionists are African-American.

NOTES[edit]

- ↑ Bruce Buschel, "Angry Young Man with a Horn," Gentleman's Quarterly, February 1987.

- ↑ Lawrence Gushee, "New Orleans-Area Musicians on the West Coast, 1908–1925," Black Music Research Journal, Vol. 9, No. 1 (Spring, 1989), 3–4.

- ↑ Tom Scanlan, "Reviewed Work: Dinosaurs in the Morning; 41 Pieces on Jazz by Whitney Balliett," Notes, Second Series, Vol. 21, No. 3 (Summer, 1964), 369–371.

- ↑ Josh Jackson, "Jazz Centennials: Legends At 100," April 23, 2009, WBGO radio.

- ↑ Brittany Talissa King, "The Color of Jazz: A White Musician’s Place in A Black World: A young musician in New York grapples with his success within a black genre," September 8, 2020.

Warning: Cannot modify header information - headers already sent by (output started at /home/jpic/philosophyofjazz.net/w/includes/WebStart.php:37) in /home/jpic/philosophyofjazz.net/w/includes/WebResponse.php on line 37

Warning: Cannot modify header information - headers already sent by (output started at /home/jpic/philosophyofjazz.net/w/includes/WebStart.php:37) in /home/jpic/philosophyofjazz.net/w/includes/WebResponse.php on line 37

Warning: Cannot modify header information - headers already sent by (output started at /home/jpic/philosophyofjazz.net/w/includes/WebStart.php:37) in /home/jpic/philosophyofjazz.net/w/includes/WebResponse.php on line 37

Warning: Cannot modify header information - headers already sent by (output started at /home/jpic/philosophyofjazz.net/w/includes/WebStart.php:37) in /home/jpic/philosophyofjazz.net/w/includes/WebResponse.php on line 37