Ontdef3. What is the definition of jazz?

“As far as I'm concerned, the essentials of jazz are: melodic improvisation, melodic invention, swing, and instrumental personality.”[1] (bold not in original)

Mose Allison (1927–2016)

“An item in Talking Machine World for July 15, 1920 says, "Art Hickman (1886 – 1930) . . . insists that his orchestra, now playing on the Ziegfeld roof, is not a jazz band. 'Jazz,' says Mr. Hickman, 'is merely noise, a product of the honky-tonks, and has no place in a refined atmosphere. I have tried to develop an orchestra that charges every pulse with energy without stooping to the skillet beating, sleigh bell ringing contraptions and physical gyrations of a padded cell.” (p. 6)

Art Hickman (1886-1930)

“In this book, The Story of Jazz, I, [Marshall W. Stearns (1908–1966)], have tried not to treat jazz, or any other music, as holy. The reason for this book is quite simple: people in the United States listen to and enjoy jazz or near-jazz more than any other music. Jazz is of tremendous importance for its quantity alone. Because of its all-pervasiveness it has a great influence on most of us. Jazz has played a part, for better or worse, in forming the American character. Jazz is a fact that should be faced and studied. Like other musics, however, jazz has its aesthetics and there are crucial qualitative differences. There is good and bad jazz, and all shades between. Further, jazz is a separate and distinct art, to be judged by separate and distinct standards, and comparisons are useful when they help to establish this point. Jazz also has an ancient and honorable history, and this book is designed to deal with these varied questions. Perhaps I should add that in Part Four, "The Jazz Age," rather than list a series of locations and personnels—work that has already been done—I tried to explore the fascinating but complex process by which jazz spreads. I see no reason to maintain the melancholy pretense of absolute objectivity. I like jazz very much, and I am no doubt biased in its favor—at least to the extent of trying to find out what it is all about.”[2] (bold not in original)

Guitarist John McLaughlin (b. 1942) was asked by JazzTimes Jim Farber:

“. . . you’ve worked with so many other great bands, from Shakti to your most recent group, 4th Dimension. Do you have a core principle that has guided you through all of it?

John Mclaughlin replied:

“I was talking about this recently with [drummer and wife of Carlos Santana] Cindy Blackman. She was telling me that she asked Wayne (Shorter), “What is the meaning of jazz?” And Wayne said, “I dare you.” [Laughs] I thought that was really cool. That means you’ve got to stand up and be yourself. It’s like when your trousers are down by your ankles. You’re naked in front of the world and you’re free. Now go and be inspired!”[3] (bold not in original)

Jon Batiste (b. 1986): “I see jazz as a superpower,” he says. “It has never depended on popularity to maintain relevance because its value is undeniable; it represents all the nuances of the human soul. It is an honor to play this music because it is my heritage—it is the Blackest, deepest American classical music that has grown to become a universal art form. Jazz shows you that something can be from a specific experience and it can be adapted in a way that’s not appropriated.”[4]

“Jazz is a strange thing. I think you really have to have played it a long time and been really involved in it to understand it. There’s something about the rhythm feel that’s not easy to learn. You have to really play it and have a history of working with it to have a jazz feeling somehow.”[5] (bold not in original)

Contents

- 1 Discussion

- 2 Controversy over Defining Jazz

- 3 Assessment of the views of Gunther Schuller and Hughes Panassié

- 4 Assessment of the views of Peter Townsend

- 5 Assessment of the views of Joel Dinerstein

- 6 Assessment of the views of Scott Deveaux and Bill Kirchner

- 7 Presentation, analysis, and critique of Alan Lawrence's views on defining jazz

- 8 Critique of Donal Fox's definition of jazz at AllAboutJazz.com

- 9 Critique of Pingouin's definition of jazz at Everything 2

- 10 Critique of Rodney Dale's definitions for jazz

- 11 Critique of Stuart A. Kallen's definition for jazz

- 12 Examination of Eric Hobsbawm's views on how to recognize jazz

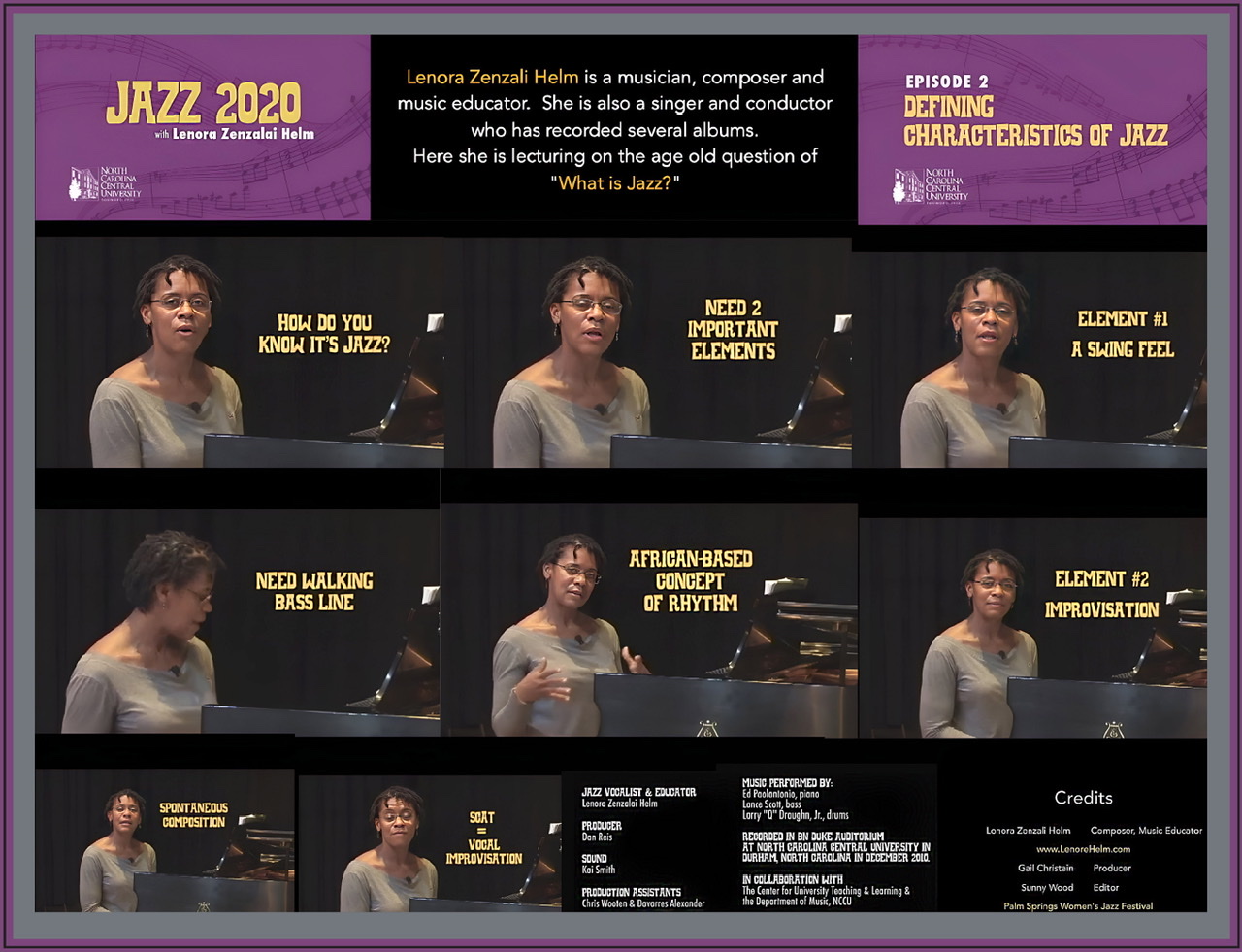

- 13 Assessment of Lenora Zenzalai Helm on defining characteristics of jazz

- 14 Assessment of the views of Jonathan McKeown-Green and Justine Kingsbury on jazz

- 15 Jazz as a natural kind

- 16 Principled Predictions of New Jazz Genres

- 17 Objections to Wilder Hobson's view that jazz cannot be defined because it is a language

- 17.1 (1) Languages can be defined

- 17.2 (2) Jazz is more than just a language

- 17.3 (3) Because languages can be defined, were jazz to be a language, then it too could in principle be defined

- 17.4 (4) Hobson has already proclaimed that the language of jazz is broader than merely “a collection of rhythmic tricks or tonal gags,” but instead reveals itself as “a distinctive rhythmic-melodic-tonal idiom.”

- 18 Wikipedia on Defining Jazz

- 19 The Etymology of "Jazz"

- 20 The Importance of Defining Jazz

- 21 Why jazz is not just an institutionally practice-mandated musical genre

- 22 What is Meant by Definition

- 23 How Jazz Can Be Defined

- 24 Does Jazz Have Essential Properties?

- 24.1 The Importance of Improvisation

- 24.1.1 Reasons to Believe A) Improvisation is "the most defining feature of" and "central" to jazz and (B) Armstrong, Ayler, Coleman, and Coltrane each played jazz improvisations are False

- 24.1.2 Reasons to Believe A) Improvisation is "the most defining feature of" and "central" to jazz and (B) Armstrong, Ayler, Coleman, and Coltrane each played jazz improvisations are True

- 24.1.3 Louis Armstrong (August 4, 1901 – July 6, 1971)

- 24.1.4 Ornette Coleman (March 9, 1930 – June 11, 2015)

- 24.1.5 John Coltrane (September 23, 1926 – July 17, 1967)

- 24.1.6 Albert Ayler (July 13, 1936 – November 25, 1970)

- 24.2 What Is Meant By Essential?

- 24.1 The Importance of Improvisation

- 25 Are There Any Necessary Conditions For Playing Jazz?

- 26 What are necessary conditions for playing jazz?

- 27 What Are Not Sufficient Conditions For Playing Jazz?

- 28 What Are Not Sufficient Conditions For Playing Jazz? — Middle

- 29 What Are Not Sufficient Conditions For Playing Jazz?—Added

- 30 Are There Any Sufficient Conditions For Playing Jazz?

- 31 Is jazz a process?

- 31.1 What are processes?

- 31.2 The processes of jazz

- 31.3 Implications for jazz being a process

- 31.3.1 Individual sonorities cannot be used to delineate jazz as a musical genre

- 31.3.2 Individual sonorities can be used to delineate jazz as a musical genre

- 31.3.3 DOWNBEAT BLINDFOLD TESTS identifying musicians by an individualized sound:

- 31.3.4 Why Rock musicians have less emphasis on having a personal idiosyncratic musical style

- 31.3.5 Why jazz musicians have more emphasis on having a personal idiosyncratic musical style

- 32 Amazon Echo's definition of jazz

- 33 Krin Gabbard's Definition of Jazz

- 34 André Hodeir's Definition of Jazz

- 35 Joachim-Ernst Berendt's Definition of Jazz

- 36 Young and Matheson's Definition of Jazz

- 37 Assessment of Thomas E. Larson's characterization of jazz

- 38 Alternative Jazz Taxonomies

- 39 Chris Washburne on the politics of defining jazz

- 40 Paul Rinzler's Definition of Jazz

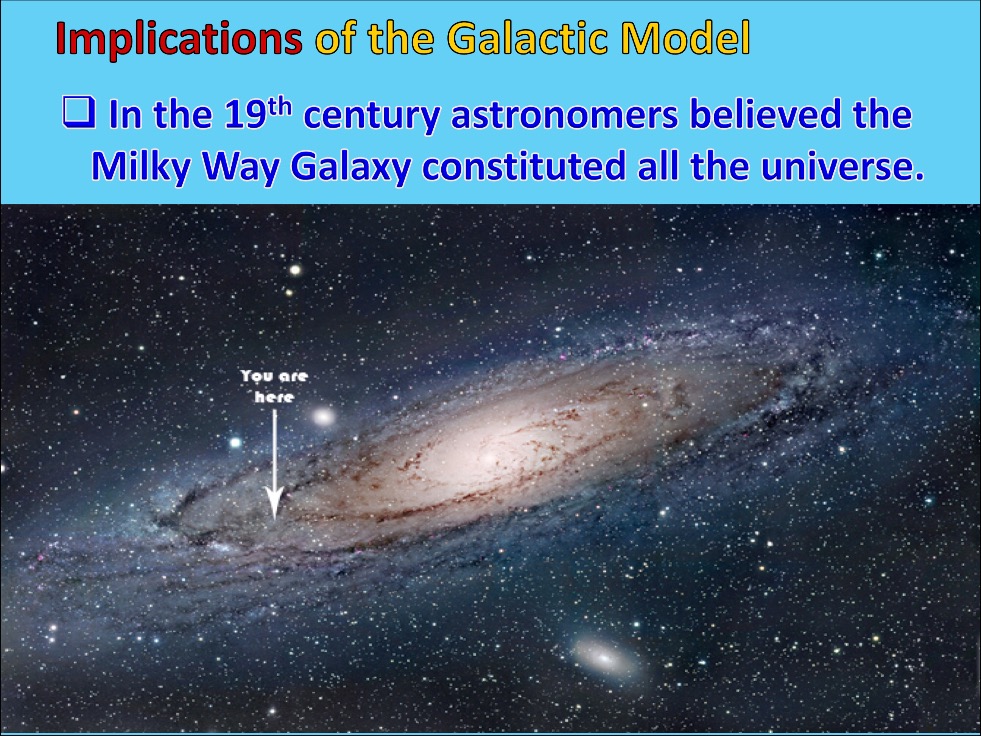

- 41 The Galactic Model for Defining Jazz

- 41.1 Why Latin, Big Band, and Free are all jazz

- 41.2 Why HSI is central to jazz

- 41.3 The Galactic Model for Jazz

- 41.4 What is Central to Jazz

- 41.5 Clearly True Claims About Jazz

- 41.6 Why need a Galactic model for jazz?

- 41.7 The Structure of a Galactic model for jazz

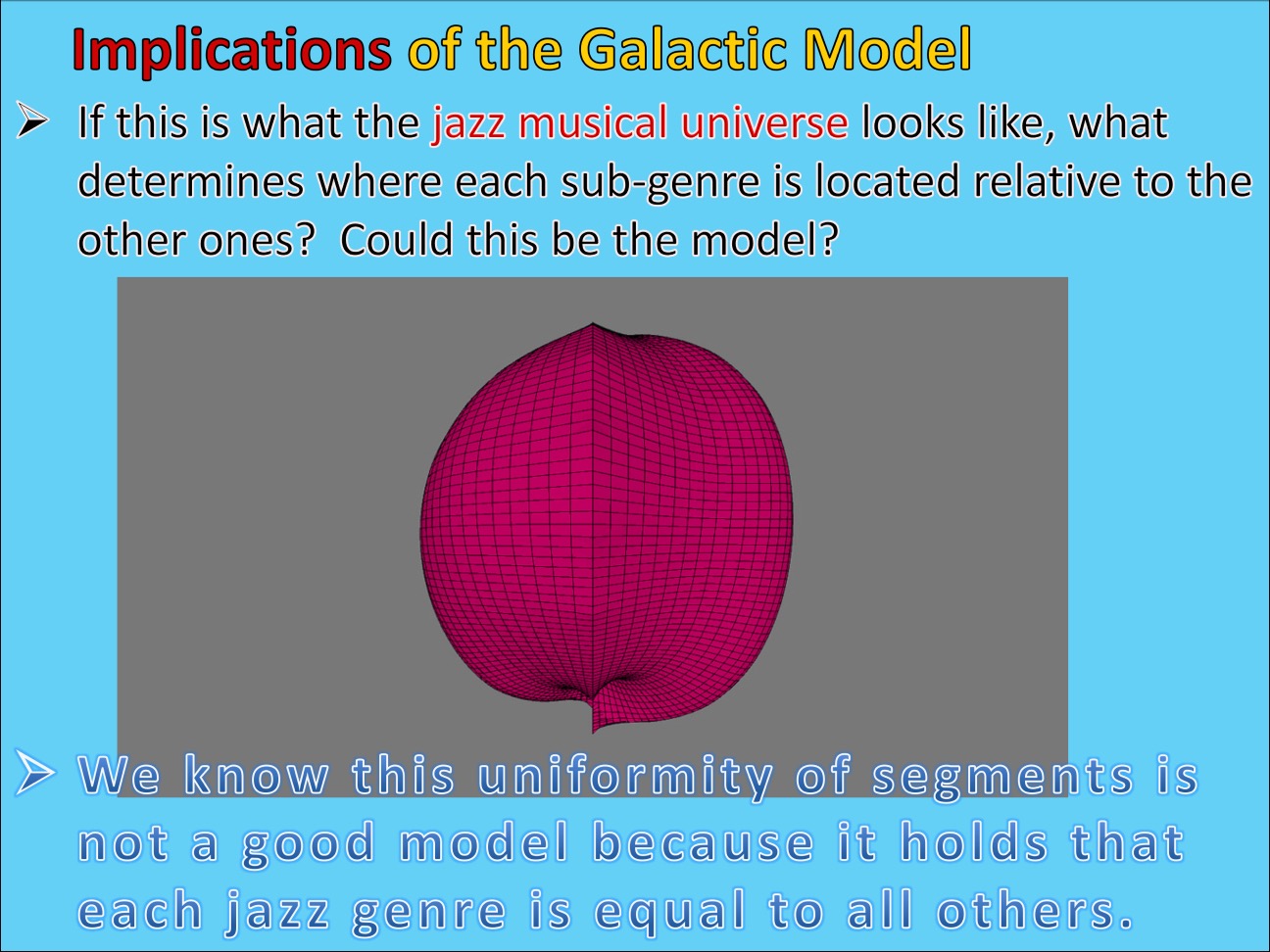

- 41.8 Implications of the Galactic model

- 41.9 Explanatory Power of the Galactic model

- 41.10 A Fatal Objection to the Galactic Model: Blues and Rock should count as Jazz, but they aren't jazz

- 41.11 A Galactic Picture of Jazz

- 42 Overview and Summary of Defining Jazz

- 43 Internet Resources on Defining Jazz

- 44 NOTES

Discussion[edit]

If you are an approved editor, then please enter any comments, questions, or arguments on the Discussion page by clicking on the word Discussion.

In the introduction to his first book, The Sound of Surprise, (1959) late author Whitney Balliett (1926-2007) wrote:

“It’s a compliment to jazz that nine-tenths of the voluminous writing about it is bad, for the best forms often attract the most unbalanced admiration. At the same time, it is remarkable that so fragile a music has withstood such truckloads of enthusiasm.”

“Jazz, after all, is a highly personal, lightweight form—like poetry, it is an art of surprise—that, shaken down, amounts to the blues, some unique vocal and instrumental sounds, and the limited, elusive genius of improvisation.”[6]

Controversy over Defining Jazz[edit]

Introduction[edit]

Numerous scholars, theorists, critics, music reviewers, and many famous jazz musicians have all disdained or pooh-poohed, or even outright rejected, the possibility of producing a successful, satisfying, and correct definition of jazz.

In 1957, Leonard Feather (1914–1994) opens his book on jazz with a belief that a definition of jazz is a "near-impossibility."

“With the belated emergence of jazz from its long-suffered role as the Cinderella of esthetics, and with its gradual acceptance in many previously closed areas, the definition of its nature, always disputed among critics and to some extent among musicians and the public, has become a near-impossibility.”[7] (bold not in original)

(For a critique of some of Feather's views see below.)

Peter Townsend states, in his Jazz in American Culture (Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2000) p. 162, that Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller, and Duke Ellington each in effect has responded to the question "What is jazz?" by replying that "If you have to ask, then you'll never know."[8] (For an assessment of some of Townsend's views go here.)

Let us reflect upon the Armstrong quotation of "If you have to ask, you will never know." Armstrong's claim does not make any sense at all. Suppose Thelonious already innately knows jazz. A mark of knowing is correctly answering questions about what it is that is known. If someone who did not know what jazz is were now to ask Thelonious what is jazz, should not a knower such as Thelonious be able to educate and inform this questioner with the correct answer? Of course, he should be able to answer the question if he already knows the answer. If Thelonious cannot answer the question, then this is strong evidence that Thelonious does not know.

Furthermore, in this scenario, the ignorant questioner after learning what Thelonious knows to be a correct conception of jazz has now learned the answer by asking the question thereby proving the blatant falsity of anyone claiming "if you have to ask, then you will never know." The very opposite is true, as all scientists agree. If you do not ask, then you will never know.

➢ Assuming for now that the above reasoning is correct, why would Armstrong/Ellington/Fats Waller make such a curious remark?[9]

Clearly, the point of this remark is to get the questioner to stop asking the question. This is most certainly an anti-intellectual response and is rejecting any possible merit to any investigation into the nature of music that qualifies as jazz. Anti-intellectual knee jerk reactions are always wrong precisely because intellectual investigations always have merit even when they are mistaken. How could anyone ever find out something is a mistake if they don't first articulate the position and viewpoint? PoJ.fm's philosophy is always to ask.[10]

In 1973 Duke Ellington (1899–1974) comments on the apparent overinclusion of too many different types of music under the jazz label.

“I don't know how such great extremes as now exist can be contained under the one heading.”[11]

Ellington asserts that jazz may have had a defined character in the past, but that by now the category of jazz is too diffuse to have a uniform definition other than it's being an American creation based on an African foundation. Ellington makes the point with these words:

“If ‘jazz’ means anything at all, which is questionable, it means the same thing it meant to musicians fifty years ago—freedom of expression. I used to have a definition, but I don’t think I have one anymore unless it is that it is a music with an African foundation which came out of an American environment.’”[12] (bold not in original)

Closely following in the footsteps of one of the first books on jazz—Winthrop Sargent's (1906–1986) 1938 publication of Jazz: Hot and Hybrid)[13]—noted jazz commentator Wilder Hobson (1906–1964) argues in his "Chapter 1: Introduction" of American Jazz Music (1939) that jazz cannot be defined because it is a language.

“It would be convenient to give a succinct definition of its form, but attempts to do so have lead only to such statements as “a band swings when its collective improvisation is rhythmically integrated.” The reason why jazz cannot be defined is the fact that it is a language. It is not a collection of rhythmic tricks or tonal gags, but a distinctive rhythmic-melodic-tonal idiom—as is, say, Japanese gaga-ku or Balinese gong music. And a language of course cannot be defined. A rude sense of it may be had by hearing it. Beyond that, what it communicates will be involved with what the hearer knows of its form.”[14] (italics authors; bold and bold italics not in original)

(For objections to Hobson's reasons that jazz cannot be defined because it is a language, see PoJ.fm's Ontdef3. What is the definition of jazz?: Objections to Wilder Hobson's view that jazz cannot be defined because it is a language)

In 2006, the authors of  Jazz: The First 100 Years,

Jazz: The First 100 Years,  Henry Martin (b. 1950) and Keith Waters (b. 1958) believe it is futile and a dead end to try to define jazz:

Henry Martin (b. 1950) and Keith Waters (b. 1958) believe it is futile and a dead end to try to define jazz:

“What is jazz? It seems proper to begin our historical discussion of jazz by defining it, but this is a famous dead end: entire articles have been written on the futility of pinning down the precise meaning of jazz. Proposed definitions have failed either because they are too restrictive—overlooking a lot of music we think of as jazz—or too inclusive—calling virtually any kind of music "jazz."”[15] (bold and italic not in original)

Benjamin Bierman[16] in his Listening to Jazz[17] (2nd ed. 2019) claims that any definition of jazz is "doomed to failure." Let's think about this for a moment. Is it even theoretically possible that there exists anything that cannot be defined? Is it not more likely that if it cannot be defined, then there just is no 'it' to begin with? This is a complex metaphysical question that needs to be explored elsewhere and so it is covered at PoJ.fm's Ontmeta8. On the impossibility of definition.

“Unlike many earlier texts, Listening to Jazz wisely refrains from attempting to define the word “jazz,” an exercise that is doomed to failure. Bierman explains why some of the more commonly cited, and ostensibly essential, elements of jazz (e.g. swing and improvisation) cannot serve as universally accepted criteria in formulating even a broad definition. Instead, he presents a cogent summary of the music’s origins and influences as well as the musical characteristics of its various styles and eras.[18] (bold not in original)

Notice that if one can provide a summary of jazz's origins, influences, and musical characteristics shouldn't one then be well on their way to a definition?

And it may well be that we don't even want a definition of jazz if they end up being like that provided by Funk and Wagnall in 1920:

“Jazz spent a lot of its childhood being ignored, derided or denounced as decadent. For example, the supposedly objective Funk & Wagnall Desk Standard Dictionary (1920) defines `jazzband' as: 'A company of musicians who play rag-time music in discordant tones on various instruments, as the banjo, saxophone, trombone, flageolet, drum and piano.'”[19]

Saxophonist and music educator Gary Bartz (b. 1940) in his "Why He Can't Teach You Jazz, But He Can Teach You Music" teaching video at JazzAcademy where he expresses disdain for jazz because he finds it too limiting. Bartz lectures that “I would like to talk to you today about the word "jazz," which I just hate, and I think everybody knows that. Because it misleads so many people down the wrong path, let me say.”

Opposed to this pessimism about the possibility of defining jazz, Peter Townsend, (senior lecturer in the School of Music and Humanities at the University of Huddersfield in England), some of whose views are examined below, writes as if it may be as easy to define jazz as it is to define anything else.

“Jazz is often thought of as being mysterious, elusive, and hard to define. But since the meaning of a word is its use, jazz is no harder to define than anything else (try defining 'popular music', for example), provided one has decided how to use the word.[20] (bold and bold italic not in original)

Not afraid to investigate whether or not jazz has an essence and can be defined is French composer, historian, and professor of music and musicology at Sorbonne University, Laurent Cugny, in his recently translated into English and published book, Analysis of Jazz: A Comprehensive Approach  (2019).

(2019).

In his book, Cugny “examines and connects the theoretical and methodological processes that underlie all of jazz” and aims to define what is a jazz work based on its features and structure, including its harmony, rhythm, form, sound, or melody. Laurent Cugny tries to show how to identify jazz. He states his positions and explains his thinking with these words

“For at least a couple of decades, the concept of essentialism has fueled a strong current of disapproval in musicology in general and in the musicology of jazz in particular. It sets out that each thing—physical object or concept—would have an alleged nature (or essence) that dictates where things stand to each other without any scope for variation or change. When understood in this sense, the concept of essentialism becomes a dreadful weapon brandished as soon as the verb to be is used and in whatever context. Not only does this attitude elude the philosophical history of the concept (which is endowed with more meanings than this particular one) but it also often tends to confuse essentialism with naturalism. The latter is a different concept that has been used in history to justify many indefensible things. Once we ensure that the differences between the two currents are made clear, I see no reason why the nature(s) of jazz in our case should be a taboo. It is thus possible to envisage that, through the many-faceted process of analyzing jazz, we may touch on the question of its essence and feel free to contribute to the debate about it. For it is certain that jazz exists.”[21] (bold and bold italic not in original)

American poet, music and cultural critic, syndicated columnist, novelist, and biographer known for his jazz criticism Stanley Crouch (1945–2020) does not shy away from the controversy over whether jazz can be defined. He at least thinks that it has central elements that virtually all reactions to jazz tend to incorporate into their music.

“I did not buy the idea that there was no definition whatsoever of jazz and that any attempt to define jazz was an attempt to "put it in a box," an idea that had come into jazz from two directions.

One direction comes from musicians of the 1960s, who considered themselves avant-garde and had rejected the word "jazz" in favor of "black music" or "creative music." When they found no takers for their wares, they angrily returned to the world of jazz—which most of them couldn't play!—and were eventually embraced by jazz critics who are, for various reasons, obsessed with exclusion and have grafted ideas about cultural relativism into the world of criticism. They love to assert, over and over, that everything is relative and jazz is whatever you choose to call it. Otherwise, they argue, you speak for an establishment trying to keep a variety of jazz musicians from receiving respect. The other direction for this thinking comes from the period in which Miles Davis and a number of first-class jazz musicians sold out to rock and produced what was eventually called "fusion," jazz-tinged improvisation over stiff, rock beats that did not swing. The result today is the instrumental pop music known as "smooth jazz."

I bought none of that. Jazz has a very solid base of Afro-American fundamentals that exclude no one of talent, regardless of color, anymore than the Italian and German fundamentals of opera do. These fundamentals remained in place from the music's beginnings in New Orleans to, literally, yesterday. Those fundamentals are 4/4 swing (or swing in any meter), blues, the romantic or meditative ballad, and what Jelly Roll Morton called "the Spanish tinge," meaning Latin rhythms. All major directions in jazz have resulted from reimagining those fundamentals, not avoiding them.”[22] (bold and bold italic not in original)

An optimistic approach towards defining jazz[edit]

Suppose we start by presuming that it is possible to define jazz, contrary to the opinion of many experts.[23]

One approach is that adapted by Marshall W. Stearns (1908–1966) in his systematic methodology of describing the history of jazz, and tracing its evolution, structure, forms and techniques from the music of Africa through the heyday of New Orleans to the present day of 1956. In his book, The Story of Jazz (see the three book covers in graphic below), Stearns touches on the main points in the development of jazz—the influence of the blues, minstrels, spirituals and ragtime, jazz of the 1920s and 1930s, the swing and bop era, Afro-Cuban music and rock and roll. He examines the styles that originated in New Orleans, Chicago, New York, St. Louis, and Kansas City, along with individual sketches of the great jazz personalities. The book also strives to provide a direct analysis of the technical elements, form and structure of jazz.

➢ How might one go about finding an effective definition for jazz?

One way would be to examine previously proposed definitions and see how they hold up under scrutiny. PoJ.fm does a critique of the many failed attempts at providing a sufficient condition for jazz that picks out all and only jazz. Many of the proposals are shown to fail at PoJ.fm's "What are not sufficient conditions for playing jazz."

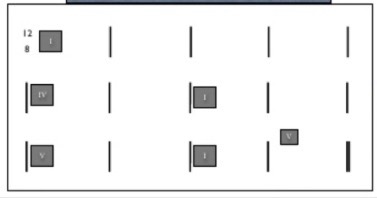

Jazz authors Mark Gridley, Robert Maxham and Robert Hoff, in their "Three Approaches to Defining Jazz" (1989), critique three types of definitions for jazz, namely,

- (1) A strict formalist definition (swing and minimal improvisation required), or,

- (2) a family resemblance approach (so that whatever has been called jazz qualifies), or,

- (3) a scalar measure of jazzness that comes in degrees and is based on past musics considered jazz.

Throughout their presentation, the three authors are critical of the three styles of definition pointing out their strengths or advantages as well as their limitations and weaknesses. Let's find out more about what are these strengths and weaknesses? Here's what they say in their "Conclusions" section.

“The overwhelming strength of the strict definition is its simplicity. And this is then the most telling weakness of the dimensional approach because the dimension approach does not allow you to make an unequivocal statement that a particular performance is jazz. The family resemblances approach and the jazzness approach are more relativistic, and they lead to fewer exclusions, having a flexibility that accommodates jazz as an evolving art form, thereby excluding far fewer performances than the strict definition excludes. The jazzness and the strict definition are both problematic because they both require us to determine the extent to which a given element is conspicuous. For example, for both the jazzness and the strict definitions, we must determine the percentage of fresh material in every performance in order to address the improvisation requirement, though this is more severe in the jazzness approach than with the strict definition. However, in the strict definition, the amount of improvisation must exceed a critical minimum before we can call the performance improvised, whereas in the jazzness approach the amount of improvisation affects only the degree to which the performance is likely to be called jazz.”[24] (bold not in original)

What the three authors appear not to notice is their lack of a complete follow through where it is justiably explained why each of the proposed jazz definitions fail as definitions. It is not merely a weakness when a strictly formalist definition excludes half of all previously understood music that was believed to be within the jazz camp, but likely catastrophic for that particular definition because it is excluding so much of what music lovers believed counted as jazz. Few think that Duke Ellington was not playing jazz even if there was no improvisation added to or diverging from the musical score of that composition.

Pre-requisites for a successful definition of jazz:

- (P1): No definition can by fiat exclude what the majority of knowledgeable jazz listeners agree qualifies as jazz.

- (P2): No definition of jazz can require that jazz must always swing because of (P1). Too much music strikes experts as jazz even when it doesn't swing, so swing is ruled out as a necessary condition. It isn't sufficient either, as argued at PoJ.fm's "What are not sufficient conditions for playing jazz."

Objections to improvisation as a necessary condition for definition of jazz[edit]

Counter-examples are one method of disproving the need for improvisation for music to be jazz.

Improvisation and swing can be found in Western Swing music, but this is more country dancing music with jazz influences, than it is jazz.

The improvisation requirement will be moot if some theorists are correct that all music from any genre is improvisational at all times to different degrees. Carol S. Gould and Kenneth Keaton in their article, "The Essential Role of Improvisation in Musical Performance" (Spring, 2000). Here the authors argue that:

- (1) Improvisation is only a matter of degree, not of kind.

“We submit that jazz and classical performances differ more in degree than in kind.[25]

- (2) Every musical performance, even previously scripted ones where performers faithfully follow a previously composed musical score involves improvisation.

If Gould and Keaton's view of improvisation being universally present in all genres of music were true, then it will not help to distinguish jazz genres from any other music genres.

For a critique that one needs to distinguish between interpretative versus compositional improvisations, see PoJ.fm Ontimpr1. What is improvisation?#Carol S. Gould and Kenneth Keaton on Improvisation.

If one requires improvisation as a requirement for music to be jazz the same judges evaluating the exact same music would end up with opposite conclusions about whether the music under consideration was jazz. Here's the example. Jazz musicians who know how to play jazz well and are now intending to play jazz perform the following tune titled "Contradiction" with these features. A three minute long song that swings throughout has the first minute with no improvisation, let's call this part 'the head,' then the second minute is improvised, with a return in the final minute to a non-improvised closing. Was this a jazz tune? It would appear so according to the strict formalist definition because there was significant swing throughout the three sections and the middle section was improvised. Also, assume that the performance of this song had many other features often found in other jazz music performances.

The strict formalist definition for jazz introduced by Gridley, Maxham and Hoff above requires all jazz music contains improvisation and uses a swing rhythm. Suppose supporters of the strict formalist definition agree that this three minute tune, "Contradiction," meets their requirements and was a jazz performance. Once it has been decided that the music performed meets all of the qualifications needed should it matter WHEN and HOW MUCH of that tune they are hearing for this music to be jazz? No, it should not matter. We record the tune under consideration specified above. We play it back to the strict definition judges. After the first minute we stop the track and ask the judges if this tune is jazz. The judges ask was anything we heard so far improvised? We tell them "No." Did it swing we ask the judges. The judges agree it did swing for that first minute that they heard. Because the first minute of the recording of "Contradictions" was swinging but not improvised the strict formalist judges conclude that the first minute of the tune "Contradictions" is not jazz because it lacks compositional improvisation. These judges have now contradicted themselves. The very same music passage of music cannot simultaneously be jazz and not jazz in any strict formalist definition. Yet this is the situation within which the strict definers find themselves. They already agreed after hearing the entire three minutes that the performance by the musicians qualifies as one of jazz, so the first minute is part of a jazz performance. It cannot also not be part of a jazz performance.

CONCLUSION: Compositional improvisation cannot be a necessary condition for every aspect of a jazz performance since parts of many jazz performances have not been improvised but rehearsed.

Objections to defining jazz using a family resemblance approach[edit]

- (2) a family resemblance approach (so that whatever has been called jazz qualifies), or,

Objections to defining jazz using a dimensional/scalar approach of jazziness[edit]

- (3) a scalar measure of jazzness that comes in degrees and is based on past musics considered jazz.

Assessment of the views of Gunther Schuller and Hughes Panassié[edit]

The Encyclopedia Brittanica entry (all Schuller quotations are from the "Jazz" article in Brittanica) written by American musicologist, composer, conductor, horn player, author, historian, and jazz musician Gunther Schuller (1925–2015), as we see below, first defines jazz, or at least attempts a detailed delineation and characterization of jazz and its origins and its musical influences, while then immediately claiming the futility of trying to define it.

(Photograph by William E. Sauro; colorized by PoJ.fm)

“Jazz, [is a] musical form, often improvisational, developed by African Americans and influenced by both European harmonic structure and African rhythms. It was developed partially from ragtime and blues and is often characterized by syncopated rhythms, polyphonic ensemble playing, varying degrees of improvisation, often deliberate deviations of pitch, and the use of original timbres.[26]

“Any attempt to arrive at a precise, all-encompassing definition of jazz is probably futile. Jazz has been, from its very beginnings at the turn of the 20th century, a constantly evolving, expanding, changing music, passing through several distinctive phases of development; a definition that might apply to one phase—for instance, to New Orleans style or swing—becomes inappropriate when applied to another segment of its history, say, to free jazz. Early attempts to define jazz as a music whose chief characteristic was improvisation, for example, turned out to be too restrictive and largely untrue, since composition, arrangement, and ensemble have also been essential components of jazz for most of its history. Similarly, syncopation and swing, often considered essential and unique to jazz, are lacking in much authentic jazz, whether [in] the 1920s or [in] later decades. Again, the long-held notion that swing could not occur without syncopation was roundly disproved when trumpeters Louis Armstrong and Bunny Berigan (among others) frequently generated enormous swing while playing repeated, unsyncopated quarter notes.”[27] (bold not in original)

➢ What are the reasons why Gunther Schuller maintains that jazz cannot be defined?

Schuller first claims that if anything is "constantly evolving and changing," it is futile trying to define it. Initially, this might seem like a legitimate reason to reject defining something because if what we are defining keeps changing its properties, then it appears that there is nothing stable enough to identify since definitions are fixed and don't change.

However, this turns out to be a weak reason against defining something. Just because things change, by itself, does not make a definition of something impossible. Consider a simple example at first. Can the word "everything" be defined and be defined accurately and well? Why, yes, it can. The definition of everything means to include all things of any kind. Dictionary.com reports the meaning of the pronoun "everything" as saying “every single thing or every particular of an aggregate or total; all.” Notice that this, on the face of it, would seem to be a perfectly acceptable and correct definition of "everything." If Schuller's constantly evolving objection were legitimate, then the pronoun "everything" could not be defined because "everything is constantly changing and evolving," although correct is irrelevant to the possibility (and actuality) of being able to determine what "everything" as a pronoun means. For two more similar counter-arguments, see Ontdef3. Arguments for the impossibility of defining jazz where it is argued automobile can be defined even though the car industry evolves and incorporates new unforeseen styles of cars, same things with motorcycles, and also Ontdef8. What is a bicycle?. Since the word "bicycle" can be defined even though new styles of bikes come into existence, the production of new unforeseen forms will not make it impossible to have a satisfactory definition.

Maurice Mandelbaum[28] (1908–1987), critiquing Morris Weitz's (1916–1981) arguments about art being an open concept in his "Family Resemblances and Generalization concerning the Arts" (1965), agrees with PoJ.fm that merely because things change and new properties may be found in new members of an older category does not necessarily make the category undefinable. Definability in philosophy often means a specification of necessary and sufficient conditions.

“What he [Morris Weitz] claims is that the concept "art" must be treated as an open concept, since new art forms have developed in the past, and since any art form (such as the novel) may undergo radical transformations from generation to generation. One brief statement from Professor Weitz's article can serve to summarize this view:

[Weitz quotation:] "What I am arguing, then, is that the very expansive, adventurous character of art, its ever-present changes and novel creations, makes it logically impossible to ensure any set of defining properties. We can, of course, choose to close the concept. But to do this with "art" or "tragedy" or portraiture, etc. is ludicrous since it forecloses the very conditions of creativity in the arts."Unfortunately, Professor Weitz fails to offer any cogent argument in substantiation of this claim. The lacuna in his discussion is to be found in the fact that the question of whether a particular concept is open or closed (i. e., whether a set of necessary and sufficient conditions can be offered for its use) is not identical with the question of whether future instances to which the very same concept is applied may or may not possess genuinely novel properties. In other words, Professor Weitz has not shown that every novelty in the instances to which we apply a term involves a stretching of the term's connotation. By way of illustration, consider the classificatory label "representational painting." One can assuredly define this particular form of art without defining it in such a way that it will include only those paintings which depict either a mythological event or a religious scene. Historical paintings, interiors, fete-champetres, and still-life can all count as "representational" according to any adequate definition of this mode of painting, and there is no reason why such a definition could not have been formulated prior to the emergence of any of these novel species of the representational mode. Thus, to define a particular form of art—and to define it truly and accurately—is not necessarily to set one's self in opposition to whatever new creations may arise within that particular form.

Consequently, it would be mistaken to suppose that all attempts to state the defining properties of various art forms are prescriptive in character and authoritarian in their effect. This conclusion is not confined to cases in which an established form of art, such as representational painting, undergoes changes; it can also be shown to be compatible with the fact that radically new art forms arise. For example, if the concept "a work of art" had been carefully defined prior to the invention of cameras, is there any reason to suppose that such a definition would have proved an obstacle to viewing photography or the movies as constituting new art forms? To be sure, one can imagine definitions which might have done so. However, it was not Professor Weitz's aim to show that one or another definition of art had been a poor definition; he wished to establish the general thesis that there was a necessary incompatibility, which he denoted as a logical impossibility, between allowing for novelty and creativity in the arts and stating the defining properties of a work of art. He failed to establish this thesis since he offered no arguments to prove that new sorts of instantiation of a previously defined concept will necessarily involve us in changing the definition of that concept. To be sure, if neither photography nor the movies had developed along lines which satisfied the same sorts of interest that the other arts satisfied, and if the kinds of standards which were applied in the other arts were not seen to be relevant when applied to photography and to the movies, then the antecedently formulated definition of art would have functioned as a closed concept, and it would have been used to exclude all photographers and all motion-picture makers from the class of those who were to be termed "artists."”[29] (bold and bold italic not in original)

Philosopher Steven Davies provides an example where one can define the concept adequately even though the scope of the things that can fall under the concept changes and new novel objects with different and distinctive properties never before included can still fall under the well-defined concept.

“With the failure of these traditional approaches, one might doubt that art is definable. Morris Weitz (1956) argues that artworks are united by a web of family resemblances, not by the kind of essence sought by a real definition. The problem with this claim is that everything resembles every other thing, so the invocation of resemblances cannot explain the unity and integrity of any concept. Weitz also maintains that definitions apply only to closed, unalterable concepts and that art, with its changing and unpredictable future, cannot be defined. Again, the claim is unconvincing. The class of meals I have eaten keeps growing and sometimes takes in new and unusual instances, but what alters is the class's membership, not its defining characteristics. It could be part, or a consequence, of the unchanging essence of art that many of its instances are created to be original in some respects.Weitz insists that, when we look and see, we do not find any property common to all artworks. He could be right about that, but what might follow is not that art is indefinable but, rather, that the defining properties are non-perceptible, relational ones.”[30] (bold and bold italic not in original)

Davies's counter-example is the concept of a meal 🥘. Dictionary.com defines a meal as “the food served and eaten especially at one of the customary, regular occasions for taking food during the day, as breakfast, lunch, or supper.”[31] Notice that meals are defined in relation to food. Davies's point also applies to the definability of the concept of food. Some Americans eat alligator steaks, but not everyone has had this type of food. When they eat alligator, it is food since the meat is nourishing. One can expand on the types of things eaten but this need not change the definition for meal, or for food: “Any nourishing substance that is eaten, drunk, or otherwise taken into the body to sustain life, provide energy, promote growth, etc.”[32]

➢ Why does Schuller think that jazz definitions must be doomed to failure?

Schuller claims that any definition of jazz at an earlier phase can be "inappropriate" when applied to a later jazz period.

“[a] definition [of jazz] that might apply to one phase—for instance, to New Orleans style or swing—becomes inappropriate when applied to another segment of its history, say, to free jazz. (bold not in original)

➢ What would make a jazz definition unsuitable, according to Schuller?

Presumably, Schuller believes that were one to use swing as a necessary component of jazz, and if free jazz doesn't swing, then free jazz couldn't qualify as jazz. Yet, it is clear from his assertions that Schuller accepts that free jazz qualifies as jazz; therefore, one should not use swing to pick out all and only jazz and, this is, indeed, what Schuller then claims!

But who says swing is the correct definition for all of jazz? Swing is a non-starter as an intrinsic property for all jazz, if not all jazz swings, which Schuller already concedes.

So, on this recommendation, don't use swing as the vital component for a definition of jazz. Nothing follows from failed attempts at a definition that would establish that defining jazz is impossible. (For more discussion on the impossibility of defining jazz, see PoJ.fm's Ontdef2. Arguments for the impossibility of defining jazz and Ontmeta8. On the impossibility of definition).

Furthermore, if Schuller accepts this reasoning that jazz is always an unstable musical genre, would it not follow that jazz should present quite a challenge to recognize. Yet Schuller, just as he had first defined jazz while denying that it was possible to do so, again appears to contradict himself when he claims jazz is "instantly recognizable" and distinguishable from "all other musical forms." How could this be possible if the subject was always "changing phases"?

“Jazz, in fact, is not—and never has been—an entirely composed, predetermined music, nor is it an entirely extemporized one. For almost all of its history, it has employed both creative approaches in varying degrees and endless permutations. And yet, despite these diverse terminological confusions, jazz seems to be instantly recognized and distinguished as something separate from all other forms of musical expression. To repeat Armstrong's famous reply when asked what swing meant: "If you have to ask, you'll never know." To add to the confusion, there often have been seemingly unbridgeable perceptual differences between the producers of jazz (performers, composers, and arrangers) and its audiences. For example, with the arrival of free jazz and other latter-day, avant-garde manifestations, many senior musicians maintained that music that didn't swing was not jazz.[33] (bold not in original)

Schuller may have had a different sort of argument in mind when he said that a “definition [of jazz] that might apply to one phase—for instance, to New Orleans style or swing—becomes inappropriate when applied to another segment of its history, say, to free jazz.” The background assumption required by his claim is that jazz develops different forms over time. The type of example he could have in mind would be if a chair existed for a time, and then a carpenter turned it into a small boat that you couldn't reasonably sit upon any longer as a chair 🪑. The previous criteria for being a chair would be inappropriate for evaluating a boat because using a chair criteria would not be an appropriate evaluative means for assessing the qualities and definition of a boat 🚣 . So, one can see that if this, namely, an earlier style of jazz's definition will not include unforeseen future radical differences in a later phase of jazz, then an initial definition for chair would be a flawed and inappropriate criterion for evaluating a future-developed boat for either the boat's chair worthiness or its boathood.

Still, jazz is hybrid music consisting of a merging of the European diatonic musical scale with an African pentatonic one. Throughout its history, jazz has incorporated and absorbed multiple musical influences from numerous, even incompatible, musical genres, including gospel, folk, blues, ring shouts, call and response, marches, and many more. Thus, perhaps jazz is like a chair boat, which helps explain some of the challenges involved in pinning jazz down.

Things can change over time more slowly so that it is easier to imagine the two falling under the same category.

➢ What things maintain their identity because of slow changes resulting in opposing properties?

A top choice has got to be humans, their bodies and their personhood, with slow changes to an individual maintaining its identity over time, resulting in having opposing properties at different times. For example, start with the human body. Except for unusual alternative philosophical perspectives, the generally accepted view is that it is the same human body from fetal formation up through death 💀. Evaluators who are biologically knowledgeable about human reproduction and human anatomy count the early formation of a unit structure from both parents remaining the same physical body because of its causal connections throughout its organically functioning (you're alive) existence. Yet, this same human body over time can have at different times contradictory properties. At birth, a head could be mostly bald, later in life completely hairy on the top of the head, then when old, one could go back to being bald. How can the same object be both hairless and non-bald? The answer is that this object has these oppositional properties at different times. The same sailing ship could first be unpainted, then painted. The paint of the ship could first be all-white 🛳 , later the same ship can be painted black ![]() . Similarly, this same type of phenomena can occur for personal identity. At one time, the very same person could first be an introvert, then later in life be an extrovert. A person could have a charming, bubbly personality, but later in life, be all gloom and doom.

. Similarly, this same type of phenomena can occur for personal identity. At one time, the very same person could first be an introvert, then later in life be an extrovert. A person could have a charming, bubbly personality, but later in life, be all gloom and doom.

Could the musical genre of jazz be like this? At one time, jazz doesn't swing, then later it does, and even later after that, it doesn't swing again? It may be possible given that Dixieland doesn't swing, then big bands do, then free jazz doesn't, if each of them still counts as being the same musical genre over time, namely each is jazz.

While it is partially true that some musicians rejected free jazz because it didn't swing, we cannot use this to rule out free jazz as a jazz sub-genre because plenty of jazz besides free jazz doesn't swing, as Gunther Schuller concedes when he states that swing and syncopation can be missing from "authentic jazz," as said in the quotation above opening this section. Much earlier jazz before swing big band music didn't swing, and some contemporary straight-ahead jazz has no swing rhythm. Swing is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for performing jazz. See PoJ.fm's "What are not sufficient conditions for jazz," and because jazz can exist that doesn't swing, it cannot be a necessary condition either.

Not all theorists agree with this. French music critic Hughes Panassié (1912–1974) held that swing was a requirement for jazz.

(Details of photographs by William P. Gottlieb; enhanced and colorized by PoJ.fm)

That this is so for Panassié is confirmed by quotations found in Jeffrey H. Jackson's Jazz French: Music and Modern Life in Interwar Paris (2008) whenever the issue is broached. For Panassié, any music that doesn't swing cannot qualify as jazz, as he makes crystal clear below:

“According to Panassié, jazz music represented a fundamental rupture in the stream of European musical style, and it demanded both a new kind of listener and a different critical audience to appreciate it. The question that the new, modern audience must ask itself is whether the music "swings." "Where there is no swing," Panassié explained, "there can be no authentic jazz." Panassié attempted, largely in vain, to describe this quality of the music. Swing "is a sort of 'swinging' of the rhythm and melody which makes for great dynamic power," he said. It is syncopation and dance, he suggested, and therefore not necessarily inherent in the melody or in how it is played. Quoting an article by Mougin, Panassié agreed that "swing is the swinging between the strong beat and the weak beat—or beats—in a measure." Such definitions were clearly tautological, but Panassié insisted that anyone acquainted with swing could recognize it objectively. Nevertheless, he quickly pointed out its subjective nature and the fact that "such a way of playing cannot be acquired by conscientious study." "Swing is a gift,"—he remarked, "either you have it deep within yourself, or you don't have it at all." On this basis, Panassié dismissed bands such as Hylton's—a recurring foil in his book—that lacked the fundamental component of swing. "An orchestra like Hylton's," he quipped, "does not, please notice, make bad jazz; it is not jazz at all." And he excluded the "symphonic style" of Gershwin and others from "real jazz" as only "distantly related to hot music."[34] (bold and bold italic not in original)

According to Panassié, swing could not be "acquired by conscientious study." Panassié's claim should come as quite a surprise to music faculty who have been teaching their jazz students how to swing for the past fifty years, at least. Enough said. So, swing is teachable, and it does not require an innate ability. When Panassié claims that "either you have it [swing] deep within yourself, or you don't have it at all," this can be proven false. Start with a beginning jazz student who does not yet know how to swing, then teach him or her how to swing, and then the proof is that before being shown, he or she could not swing, but after instruction and training, the student now can swing musically. Our thought experiment proves that swing is not innate and can be acquired through education and training, as has now been known by jazz students and jazz faculty for at least the last fifty years.

“No music could be real jazz if it did not swing, but there was more than one way for a band to do so. Real jazz could be played straight or hot. To play "straight" meant "playing the piece just as it is written, without modifying it." Straight performances were tied to the notes on the page, yet they could be done in a swinging style. To play hot "means to play with warmth, with heat.' and was based on variations of melody and intonation that were improvised anew with each performance." Although both hot and straight were still real jazz because both were based on swing, Panassié elevated hot music as the ultimate form. It came from the personalized interpretation of a composition given to it by each musician rather than merely playing the notes as they appeared on the page. Hot jazz, he said, came from the musician's soul.[34] (bold and bold italic not in original)

Even in 1958, jazz writer and music critic Nat Hentoff finds Panassié's parochial tastes too limiting if they end up eliminating from the jazz pantheon the musical works and jazz musicians from the later and more modern jazz sounds of Bebop and beyond, including the improvisational mastery of Charlie "Yardbird" Parker, or the fiery trumpet work of Dizzy Gillespie, or the many modern styles of jazz represented by the music of Miles Davis.

“In view of Panassié's religious belief that most modern jazz isn't jazz at all, do not expect to find any records by [Charlie] Parker, [Dizzy] Gillespie, [Miles] Davis, etc.[35] (bold and bold italic not in original)

➢ Who counts as legitimate jazz musicians, according to Panassié's discography of jazz?

Nat Hentoff tells us some of the musicians Panassié includes in his jazz discography:

“There are large sections for [Duke] Ellington, Coleman Hawkins, [Fletcher] Henderson, [Jimmy] Lunceford, [Count] Basie, Big Bill (Bissonnette), [Earl "Fatha"] Hines, [Fats] Waller, and [Chick] Webb, among others. The often eerie imbalance caused by Panassié's pontifical taste leads not only to the omission of the moderns but to the inclusion of only four Billie Holiday titles contrasted with over ninety for [Mezz] Mezzrow who is, Panassié assures us, the only white man capable of playing the blues like a Negro.”[35] (bold and bold italic not in original)

In the "Preface" to the 1960's revised and expanded edition of The Real Jazz (initially written in 1942), Panassié emphasizes that he has changed his mind regarding his prior assessments of real jazz players, having been based too much on only hearing white jazz musicians. He now realizes his previous estimates of players resulted from his inexperience in hearing excellent African-American musicians. He now claims INSERT QUOTATION "jazz is black music" and what counts as good (he says "real") jazz, and he is not so humble as not to contradict his prior estimates of the best jazz players. INSERT QUOTATIONS.

Ironically, he is still wrong in his assessments and probably somewhat for the reasons he gives for his previous misjudgments, namely lack of exposure to the music and how it gets produced. He leaves out the modern players of Bebop that were available for hearing from 1946–47 onwards. Indeed, when he wrote the original 1942 volume, we can forgive him since Bebop had not yet been formed. In a revised 1960 edition, Panassié no longer has any excuse for excluding the most modern jazz musicians of this period.

Panassié recognized an essential point about (good) jazz performers. They must themselves be excellent composers because they are improvising concurrently with their playing. (See PoJ.fm's Ontimpr1. What is improvisation?).

“Panassié emphasized the importance of improvisation to hot jazz precisely because it shifted the traditional balance between composer and performer, thus producing another distinction between jazz and art music.[34] (bold not in original)

Having made this observation that helps distinguish jazz from non-improvised music, it should be a surprise for Panassié to exclude Beboppers from his jazz universe. The Beboppers were superior improvising composers, plus a fascinating thing about this whole debacle of Panassié's is that much of Bebop did swing! For an outstanding example of a swinging song, listen to "Star Eyes" on Amazon or Youtube's original album version of "Star Eyes" by the Charlie Parker quartet recorded in 1951 with Miles Davis on trumpet, Walter Bishop, Jr. on piano, Teddy Kotick on double bass, and Max Roach on the drums, or the even hotter live version of "Star Eyes" at Youtube.

Anyone who recognizes swing will undoubtedly hear it in this tune. At this point, Panassié could go one of two ways, both disastrous for his exclusion of more modern jazz performers. Either he could agree that "Star Eyes" is swinging so counts as jazz, proving Bebop should not automatically be excluded from jazz or all of the modern players who have performed the song, or Panassié could deny that "Star Eyes" was a Bebop song, which it is when Bird plays it, so that he would be wrong again.

Assessment of the views of Peter Townsend[edit]

In his book, Jazz in American Culture (pictured here)

Peter Townsend, at the time of his book's publication in 2000 was a Senior Lecturer in the School of Music and Humanities at the University of Huddersfield, writes about the question of defining jazz. He seems initially to state that there is no problem defining jazz, then proceeds to cast doubt on that suggestion.

“Statements about jazz beg questions of definition. Jazz is often thought of as being mysterious, elusive, and hard to define. But since the meaning of a word is its use, jazz is no harder to define than anything else (try defining 'popular music,' for example), provided one has decided how to use the word. The preferred definition of jazz in this book stays close to the musical basis for the reasons already stated. But jazz can be defined relatively narrowly or relatively broadly. Some writers have restricted its usage to the musical styles they prefer, like the 1940's revivalists who denied the word 'jazz' to any of the post-New Orleans styles. On the other hand, some recent exponents of Jazz Studies have expanded the term to include the entire phenomenon of jazz, including all its representations, derivatives and social implications. These shifts in the meanings of the word could be made transparent by other signals, such as marking them 'jazz (1),' 'jazz (2)', 'jazz (3),' and so on. It is probably wiser to accept Krin Gabbard's conclusion that jazz is 'the music that large groups of people have called jazz at particular moments in history,' and then to use the word in the sense that emphasizes the qualities that one considers important.”[20] (bold not in original)

When Townsend remarks above in his opening sentence that "statements about jazz beg questions of definition," he is not referring to the well-known fallacy by the same name wherein a premise presupposes the truth of its conclusion. Instead, he merely means that someone should ask the question of what is jazz. His second sentence stating that jazz is no harder to define than anything else is implausible. If jazz were so easy to identify, why doesn't Townsend go ahead and define it?

Merely deciding how one will use the word "jazz" brings us little closer to defining it successfully. (See PoJ.fm's Ontmeta8. Stipulative definitions explaining the issues with such definitions). But suppose we follow Townsend's advice and say we decide how we want to use the word "jazz" for a style of music that we distinguish from other genres of music that are non-jazz. Now we know how we want to use the word, but there remain unanswered questions as to the features of jazz that can distinguish it from other non-jazz music. Townsend remains mute on this hard question even though he claims not to when he states that his (or anyone's) 'preferred' method for defining jazz "stays close to the musical basis."[20] But what is that musical basis, and how can we use it to distinguish jazz from non-jazz?

As can be seen, many, many possible musical bases fail sufficiently to distinguish jazz from non-jazz regardless of how jazz gets defined more broadly or more narrowly. (See Ontdef3. What are not sufficient conditions for playing jazz?). Townsend's suggestions do not work whether one tries a narrower or a broader approach. First, consider his narrow proposal of limiting jazz to "the 1940's revivalists who denied the word 'jazz' to any of the post-New Orleans styles."[20] This doesn't work if one believes jazz includes music other than just a New Orleans Dixieland style. If we stuck to this definition, then almost all other music that has been called jazz would be excluded from being jazz, and this is just unacceptable. It would eliminate virtually all jazz music developed since the 1940s, which is the vast majority of music that has been (correctly) thought to be jazz, including Bebop, big band swing, modal, cool, soul, or even the more suspect jazz-rock fusion, smooth jazz, free jazz, and so on. Hence, drawing too narrow a boundary around jazz excludes music that most theorists wish to include at least some other types other than just New Orleans styles of jazz.

Townsend next notes, second, a broader definition of jazz that “expand(s) the term to include the entire phenomenon of jazz including all its representations, derivatives and social implications.”[20] Does this help better to define jazz? Not really. First, music's representations and derivatives are far from being clear. What are these? Is a jazz event a derivative or not? Are Matisse's jazz series of paintings a representation of jazz, and to what extent?[36] Likely Townsend believes that the most significant of these three (representations, derivatives, and social implications) is the social implications. Consider, however, that a genre of music's social implications might mirror and be the same as a different genre of music. Two different types of music could have the same social connections, as may, for example, possibly be true of the equally African-American inspired music labeled the blues. If blues and jazz had comparable social effects, then bringing in social implications may well not permit distinguishing jazz from non-jazz. Furthermore, suppose that both of the following claims were true: (T1) Free jazz is a form of jazz, but (T2) Free jazz has some different social implications (as well as various representations and derivatives) than other types of straight-ahead jazz. If true, and it is incredibly likely that it is, social implication differences are irrelevant for defining jazz were (T1) to be accurate, which it probably is since free jazz has less overall social acceptability than has straight-ahead jazz. On this basis, free jazz could not be considered jazz were these social implications of free jazz different than those for straight-ahead jazz, thereby contradicting (T1).

Townsend then finally settles on accepting a suggestion by Krin Gabbard's that “jazz is "the music that large groups of people have called jazz at particular moments in history" and then to use the word in the sense that emphasizes the qualities that one considers important.”[20] Neither of these suggestions is useful or acceptable for defining jazz. We cannot just accept as an intellectually satisfying definition of jazz that it is a music determined by what people have called jazz since some music that has used the nom de plume of jazz, such as acid jazz, turned out not to be jazz. (See Ontdef3. Why 'so-called' acid jazz is not a sub-genre of jazz). Emphasizing the conditions that you think are important is just as much another failed suggestion if the qualities you find essential are found in other music genres besides jazz. If you believe that swing were essential to jazz, it turns out that this feature is unhelpful for defining jazz since some non-jazz music has swing, such as rockabilly music or western swing, and some jazz fails to swing as does much modern mainstream jazz, not to mention free jazz or Latin jazz.

“A related premise of this book is that what is called jazz is, in any case, a certain segment or area selected out of a continuous terrain of American musical styles. It has no precise boundaries, and at its fringes it shades off into a range of other musics. The territory of jazz touches 'pop' music, 'country' music, the blues, 'classical' music, rock and roll, and so on, and at times can hardly be distinguished from them. There are styles and artists that pose questions about boundaries and classifications: was Frank Sinatra a jazz singer? Was Louis Jordan a jazz musician? Was 'Western Swing' part of jazz or of country music? The idea of the limits of a music like jazz, of its boundaries, should be reassessed in the way that Gregory Nobles proposes for the idea of the 'frontier': as an area characterized by a 'complex pattern of human contact,' not simply as a cut-off point between well-defined separate entities!”[37] (bold not in original)

Regarding the boundaries of jazz as a style of music, Townsend may well be correct that when we get into more fringe types of musical areas that jazz can be more undetermined as jazz. Paul Rinzler supports the idea that jazz boundaries can be ragged in his masterwork, The Contradictions of Jazz, where Rinzler defends that one should understand jazz as having a fuzzy logic whereby jazz can be along a continuum with varying strengths and degrees of jazz. Still, Townsend appears to go too far if he believes that there are times when jazz “can hardly be distinguished from” pop music, or country, the blues, classical music, or rock and roll. While it is true that Third Stream is a combination of classical music and jazz and jazz/rock fusion synthesizes jazz with rock, it still is hyperbolic to proclaim that jazz and these other forms at the fringes cannot be distinguished from each other.

Townsend continues his development of these lines of thought by marking jazz out as a region of music.

“Jazz is more like a region than a nation. Nevertheless, it is still possible to state some positive characteristics that mark out the region. For positive definitions, one can refer to a useful brief version by Lewis Porter: "Jazz is a form of art music developed by black Americans around 1900 that draws upon a variety of sources from Africa, Europe, and America." Jazz as a segment of American music is, by a consensus of most writers, identifiable by reference to its rhythms, its repertoire, its use of improvisation and its approach to instrumental sound and technique, and these features are reflected in the description of jazz as a music in Chapter 1.”[37] (bold and bold italic not in original)

Staying with his fundamental approach of defining jazz in musical terms, Townsend proposes to accept what he finds to be a "useful version" for determining jazz put forth by Lewis Porter. If we evaluate Porter's suggestion as a way to define jazz, it is easy to see that Porter's description remains unsuccessful for the primary reason that it applies equally to blues music that was also primarily developed by African-Americans around the turn of the century with musical sources deriving from Africa (using a pentatonic scale), Europe (using a diatonic musical scale), and (North) American influences (work songs, call and response, gospel, and so forth).

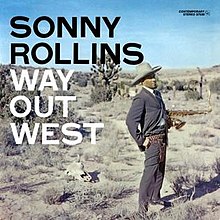

Lastly, the idea that jazz can be identified by its rhythms, repertoire, improvisational sonic techniques, and approaches is welcomed, but also cannot be by themselves either necessary or sufficient conditions for jazz. (See PoJ.fm's Ontdef3. What are necessary conditions for playing jazz? and Ontdef3. What are not sufficient conditions for playing jazz?). Is there such a thing as a distinctive jazz rhythm only used in jazz music? This doesn't sound correct. Certainly, repertoire cannot distinguish jazz from non-jazz because many jazz standards came from non-jazz songs, such as Sonny Rollins's "I'm an Old Cowhand" from Rollin's album "Way Out West," or his jazz version of "Surrey with the Fringe on Top," or all of the jazzers who covered it, or John Coltrane's "My Favorite Things" from the non-jazz musical "The Sound of Music" that no one considered this song to be jazz until performed by Coltrane.[38] Many non-jazz kinds of music incorporate improvisation into their respective non-jazz musical genres, including Indian ragas from Indian classical music, country, blues, rock, rap, and on and on. Hence, while certainly relevant to jazz, Porter's list does not yet constitute a definition that would pick out all and only jazz.

Assessment of the views of Joel Dinerstein[edit]

Joel Dinerstein, author of numerous tomes on coolness, when reviewing John Gennari's book, Blowing Hot and Cold, holds that jazz critics managed a "unique intellectual achievement" by developing, shaping, and codifying the 'formal categories' by which jazz is to be analyzed and understood. Here is how he puts these claims:

“Blowin’ Hot and Cool [by John Gennari] simultaneously functions as a history of jazz, an intellectual history of jazz, and a survey of jazz discourses—no small feat—all as rendered through the guru of the jazz critic. As opposed to jazz musicians, who have often refused to categorize jazz, “emphasiz[ing] the social messages embodied in the music,” the achievement of a personal sound, and “jazz . . . as a form of communal bonding, [and] ritual,” jazz critics have inhabited a range of modernist stances predicated on cross-racial exchange. [John] Gennari casts the music’s white proselytizers, columnists, and impresarios along a continuum of paternalism, patronage, friendship, primitivism, and vernacular patriotism, and its black writers and impresarios (Amiri Baraka, Stanley Crouch) as tightrope walkers of integrationist and separatist ideologies, cultural affirmation and diasporic identity, neoclassicism and avant-gardism. From the moment John Hammond and Leonard Feather stepped into the Savoy Ballroom in 1935 with the explicit intention not to dance but to listen—“the Ur-stance of the jazz critic”—they positioned themselves as discursive gatekeepers “distinct from the dancing mass body, caught up in an imagined sense of privileged intellectual and emotional communion with the music.” Gennari seeks neither to redeem nor delegitimize their cultural work but to highlight their unique intellectual achievement: they shaped an undervalued popular music into a vernacular art music by successfully creating the formal categories through which the music is understood.[39] (bold and bold italic not in original)

➢ Is it true that jazz writers and critics are fully responsible for the categories used to analyze and appreciate jazz?

Doesn't this emphasis on jazz writers and critics (presumably for both Gennari and Dinerstein) production of formal jazz categories and concepts used to 'understand' jazz ignore another important causal source for jazz category analytical constructions, namely the jazz musicians and their compositions themselves? Don't we want to give some credit to the performers of the music themselves, and not just to the people who write about jazz phenomena? Should not Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington, Stan Kenton, Ornette Coleman, etc. be given credit and responsibility for the, as Dinerstein writes it, development of the "formal categories through which the music is to be understood"?

If the above musicians had not developed their compositions that helped produce bebop, or big band compositions representing themes, such as Ellington's "Black and Tan Fantasy," or Mary Lou Williams's 'sacred music,' or the harmolodic style of music developed by Ornette Coleman and his players, or George Russell's, "Jazz in the Space Age," third stream style, there would not exist the music that jazz writers and critics end up analyzing with their 'formal categories.' If the music itself did not exist, there would be nothing for the writers to discuss, or anything for that matter to analyze. Doesn't the source for the formal categories, the musicians and musical compositions, themselves shape what those categories are to become? It would seem so.

Assessment of the views of Scott Deveaux and Bill Kirchner[edit]

Some people believe that jazz and its concept may conform to Morris Weitz's (1916–1981)

(Morris Weitz 1916–1981)

This point of view is represented by Scott Deveaux, Professor of Critical & Comparative Studies at the University of Virginia in the McIntyre School of Music, holding that one should avoid defining jazz “in musical terms.”

(Scott Deveaux b. 1954)

Deveaux explains:

“Defining jazz is a notoriously difficult proposition, but the task is easier if one bypasses the usual inventory of musical qualities or techniques, like improvisation or swing (since the more specific or comprehensive such a list attempts to be, the more likely it is that exceptions will overwhelm the rule).”[42] (bold not in original)

But herein lies madness. How else could one come up with a definition of jazz as music if one ignores its "musical qualities," as recommended by Deveaux? Of course, for anyone who thinks that there is nothing in common between different jazz genres and that they have just been lumped together under the jazz umbrella due to historical accidents, this would be a way to ignore jazz's musical qualities. For more discussion on these points, see PoJ.fm's Ontdef3. Why jazz is not just an institutionally practice-mandated musical genre.

Undaunted, Deveaux continues by providing various reasons for rejecting jazz/rock fusion or free jazz/the new thing/avante-garde as qualifying as jazz. You should be especially sensitive when reading the below quotation for what would appear to be a blatant contradiction in his theory. First, he denies that jazz can be defined, yet below argues that there is nevertheless an "essential nature to jazz" and then second, adds insult to injury by claiming the essential nature of jazz "is the process of change itself" while incredibly denying that jazz fusion and free jazz qualify as jazz even though these are the very changes to which he refers.

“Much as the concept of purity is made more concrete by the threat of contamination, what is not is far more vivid rhetorically than what it is. Thus fusion is "not Jazz" because, in its pursuit of commercial success, it has embraced certain musical traits—the use of electric instruments, modern production techniques, and a rock- or funk-oriented rhythmic feeling—that violate the essential nature of jazz. The avant-garde, whatever its genetic connection to the modernism of 1940's bebop, is not jazz—or no longer Jazz—because, in its pursuit of novelty, it has recklessly abandoned the basics of form and structure, even African-American principles like "swing." And the neoclassicist stance is irrelevant, and potentially harmful, to the growth of Jazz because it makes a fetish of the past, failing to recognize that the essence of Jazz is the process of change itself.”[43] (bold not in original)

How can there be "contamination" on Deveaux's jazz views if the nature of jazz is to change? The only way to change is to incorporate 'contaminations' into jazz, so he contradicts himself again.

Deveaux is far far from being alone in rejecting the possibility of defining jazz. For example, this belief that it is fruitless to try to define the nature of jazz music appears to be the view of Bill Kirchner, in his “Introduction” to The Oxford Companion to Jazz, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 5):

“Throughout the—roughly speaking—century-old history of jazz, there have been numerous attempts to ‘define’ what the music is or isn’t. None of these has ever proven successful or widely accepted, and invariably they tell us much more about the tastes, prejudices, and limitations of the formulators than they do about the music. You’ll find no such attempts here.”[45] (bold and bold italic not in original)

Presentation, analysis, and critique of Alan Lawrence's views on defining jazz[edit]

At All About Jazz, author Alan Lawrence gives his views on problems with defining jazz in his article What is jazz? Part Two (December 9, 2002). To make it easier to assess the merits of Lawrence's assertions (in green font), critique of his remarks are interspersed in blue font.

What is jazz? Those three words form one of the toughest questions in music. Ask a hundred people and you are likely to get as many different answers.

That there might be diversity in people's answers on how to define jazz is not relevant for whether or not there can be an adequate or useful definition of it. If you asked 100 people to define gall bladder, you would get a lot of blank stares and different answers, but this would in no way show that gall bladder cannot be identified. The gall bladder is the small sac-shaped organ underneath the liver where bile is stored upon secretion by the liver and before its release into the intestine.

In fact, we don't want to ask random people for their opinions about jazz. Instead, we want to address music experts and especially those knowledgeable about jazz. Here it seems apparent that many many responses from the experts would be in accord with each other. There would be less diversity. Additionally, the fact that some genres of jazz are found suspicious by some experts would not show that of the music that virtually all experts agree is incontestably jazz that there may be something in common with the incontestable jazz that one could use to define it.

Few things have given me more pleasure in life than listening to the music we call jazz. Even after hearing several thousand recordings in over 15 years and seeing countless live shows, I cannot offer a definitive definition of the word "jazz."

The fact that Alan Lawrence cannot define jazz says nothing about whether or not jazz can be defined. Perhaps Lawrence cannot delineate what is a gall bladder either. Suppose he worked at a butcher shop and had seen thousands of cow gall bladders. It still wouldn't follow from Lawrence's ignorance about the function of a gall bladder that this organ cannot be defined.

The challenge may lie in the term "jazz" itself. Can a living music, one that may well be the most colorful and varied art form in the world, be defined by a single word?

Is this a believable claim? Absolutely not! Art itself in the wide-open art world is much more "colorful and varied" than jazz. Art in the art world includes many styles and types of art, from conceptual art to Impressionism and from Pop art to earthwork installations to Christo's wrapped island to Chris Burden having himself shot with a .22 caliber gun in the arm. Now there's some real variety in action with a living art world continually challenging itself, and all of it is under the same one word "art."