Ontmeta0. What is the philosophy of jazz?

“Jazz too, evolving from humble beginnings that were sometimes hardly more than sociological manifestations of a particular American milieu, has developed as an art form that not only possesses a unique capacity for individual and collective expression, but in the process of maturing has gradually acquired certain intellectual properties. Its strength has been such that it has attracted interest in all strata of intellectual and creative activity. It is natural and inevitable that, in this ever broadening process, jazz will attract the hearts and minds of all manner of people with all manner of predilections and temperaments even those who will want to bring to jazz a roughly 500 year old musical idea, the notion of thematic and structural unity.”[1] (Gunther Schuller in his "Sonny Rollins and the Challenge of Thematic Unity," The Jazz Review, Vol. 1, No. 1 (November, 1958)) (bold and bold italic not in original)

Contents

- 1 Best practices for a philosopher of jazz

- 2 Theodore Gracyk on questions in the philosophy of jazz

- 3 Why is jazz interesting to philosophical reflection?

- 3.1 Brushing teeth and sock washing do NOT involve basic concepts about “ourselves and the world”

- 3.2 Brushing teeth and sock washing DO involve basic concepts about “ourselves and the world”

- 3.3 Why Feige's definition of philosophy is too BROAD

- 3.4 Why Feige's definition of philosophy is too NARROW

- 4 Why have a philosophy of jazz?

- 5 The need for multimedia argumentative platforms and delivery vehicles

- 6 Why use hypertext?

- 7 Problems for defining jazz

- 8 PoJ.fm chats with ChatGPT (January 30 2023 version) on topics in the philosophy of jazz

- 9 PoJ.fm chats with ChatGPT (January 30 2023 version) on answers to Gracyk's topics in the philosophy of jazz

- 10 Internet Resources on the Philosophy of Jazz

- 11 NOTES

Best practices for a philosopher of jazz[edit]

“Rather, the working jazz writer is (or should be) a well-informed, competent journalist with the capacity to enjoy and understand what he hears and the skills to communicate the enjoyment and understanding. He should also be a responsible reporter and an honest man. If additionally he possesses the qualifications to produce, when requisite, “serious criticism,” so much the better, and if he is a good writer with a clear style, best of all.

His true function, Zwerin to the contrary notwithstanding, is to deliver to his readers informed ideas and opinions about music and musicians in a coherent manner, with the purpose of stimulating interest in the subject, heightening understanding and/or appreciation of a performer and his work and, ultimately, developing in his readers the capacity for discrimination between the good and the inferior. He should not address himself to those who are “indifferent in front,” unless he is conducting a crusade to convert the masses, but rather to those who already share his interest and enthusiasm for the music but lack his background and insight.”[2] (bold not in original)

Theodore Gracyk on questions in the philosophy of jazz[edit]

In an interview with Richard Marshall, philosopher of jazz Theodore Gracyk covers many questions that interest philosophers of jazz.

Here Gracyk discuss:

- The philosophy of jazz,

- Why heed a philosopher regarding jazz (or anything)?,

- Whether a unified definition of jazz can be given,

- Jazz and race and gender,

- Jazz as Nietzschean Dionysian festival,

- The interface between jazz and white minstrelsy, blackface, and appropriation,

- The politics of identity and appropriation raised by rock music,

- Improvisation,

- Nelson Goodman,

- Can improvisation be flawed?,

- Is all music art?,

- Do ideas imposed on art interefere with aesthetic responses?,

- Contextualisation,

- The distinction between art and aesthetic and analytic/continental approaches.[3]

Read ChatGPT's (January 30, 2023 version) responses to these topics below.

Why is jazz interesting to philosophical reflection? [edit]

Professor of Philosophy and Aesthetics at the State Academy of Arts and Design Stuttgart (Akademie der Bildenden Künste Stuttgart) Daniel Martin Feige[4] has written his bookon the Philosophy of Jazz  (2014)[5], that has two primary goals:

(2014)[5], that has two primary goals:

We can raise questions about these two goals and seek justified answers.

Feige asserts that some subject matters are not worthy of philosophy's efforts to investigate. He explains why given his conception of the nature of philosophical reflection.

“Of course, the subject of philosophy is not just any arbitrary concept. A philosophy of brushing teeth or washing socks would hardly be worth the effort. Rather, the subject matter of philosophy is the basic concepts essential for our understanding of ourselves and the world. These are terms without which we could not adequately understand ourselves as the rational living beings that we are. Therefore, one can briefly say: Philosophy is a reflective science that aims to clarify the basic concepts that are essential for our understanding of ourselves and the world.”[7] (bold and bold italic not in original)

We should start by asking if these claims are valid. Feige disdains philosophical 🧐 studies of brushing teeth or sock washing.

➢ What are his purported reasons for rejecting philosophical investigations of teeth brushing or sock washing?

Presumably, Feige believes these mundane activities do not involve “basic concepts that are essential for our understanding of ourselves and the world.” There are two immediate concerns. First, is Feige's characterization correct about the nature of philosophizing? To avoid a complicated discussion, let's assume that his depiction of philosophy is accurate for just now, but see below for a critique. Second, is he correct that brushing teeth and sock washing do not merit philosophical investigation because these activities do not involve "basic concepts essential to understanding ourselves and reality"? Are there any subject matters that philosophy should not bother to investigate? Consider both sides of the answers.

Brushing teeth and sock washing do NOT involve basic concepts about “ourselves and the world”[edit]

Brushing one's teeth does not require any analysis. There is nothing of philosophical significance that could be discovered by conceptual analysis of brushing or the nature of teeth. To the extent one wishes to learn more, or investigate brushing or teeth, would require a scientific investigation, but not a philosophical one. Science can analyze a tooth (plural noun) as “a hard, calcified structure found in the jaws (or mouths) of many vertebrates and used to break down food. Some animals, particularly carnivores, also use teeth for hunting or defensive purposes.”[8]

Brushing teeth and sock washing DO involve basic concepts about “ourselves and the world”[edit]

Feige appears to assume that we can sharply distinguish between science and philosophy, but we cannot because it is a matter of degrees and fuzzy boundaries. For a presentation of some of the reasons, see John Searle's "Contemporary Philosophy in the United States," Blackwell's Companion to Philosophy, p. 7 where Searle concludes:

“Most philosophers today accept some version or other of Quine's rejection of the analytic-synthetic distinction. Not everybody agrees with his actual argument (I, for one, do not), but now there is general scepticism about our ability to make a strict distinction between those propositions that are true by definition and those that are true as a matter of fact. The rejection of the analytic-synthetic distinction has profound consequences for analytic philosophy, as we shall see in more detail later. At this point it is important to state that if there is no well-defined class of analytic propositions, then the philosopher's propositions cannot themselves be clearly identified as analytic. The results of philosophical analysis cannot be sharply distinguished from the results of scientific investigation. On the positivist picture, philosophy was not one among other sciences: rather, it stood outside the frame of scientific discourse and analysed the logical relations between, on the one hand, that discourse and its vocabulary and, on the other, experience and reality. Philosophers, so to speak, analysed the relation between language and reality, but only from the side. If we accept Quine's rejection of the analytic-synthetic distinction, then philosophy is not something that can be clearly demarcated from the special sciences. It is, rather, adjacent to, and overlaps with, other disciplines. Although philosophy is more general than other disciplines, its propositions do not have any special logical status or special logical priority with regard to the other disciplines.” (bold and bold italic not in original)

Philosophy's earliest history included what is now considered the scientists' domains, such as psychology, sociology, linguistics, and economics.[9]

One can argue that the definition of philosophy Feige provides is both too broad and too narrow.

Why Feige's definition of philosophy is too BROAD[edit]

He claims that philosophy only considers “basic concepts that are essential for our understanding of ourselves and the world.” Consider what counts as being either about 'ourselves' or 'the world.' Unfortunately, this includes everything since there is nothing left out. Because we are in the world, the reference to 'ourselves' is also unnecessary and redundant; this ourselves interest is only there to show we have a particular interest in ourselves. Hence, Feige's definition of philosophy is too broad since it leaves nothing out. If we include the world, then since this excludes nothing, philosophy studies basic concepts about everything. On such a line of thinking, Feige would need to have the possibility of philosophical investigations into basic concepts about teeth brushing and sock washing.

Why Feige's definition of philosophy is too NARROW[edit]

Some philosophers might argue that the principles of logic, those involved in the study of good and bad reasoning, are neither about ourselves nor about the world. Since logic is definitely a field of study taken up by philosophers, Feige's conception that only includes analysis of basic concepts about 'ourselves' and 'the world' is too narrow; it excludes fields studied by philosophers.

"Is Logic Empirical?"

“What is the epistemological status of the laws of logic? What sort of argument is appropriate for criticizing purported principles of logic? In an influential paper entitled "Is Logic Empirical?" Hilary Putnam, building on a suggestion of W. V. Quine, argued that in general, the facts of propositional logic have a similar epistemological status as facts about the physical universe, for example, as the laws of mechanics or of general relativity, and in particular that what physicists have learned about quantum mechanics provides a compelling case for abandoning certain familiar principles of classical logic: if we want to be realists about the physical phenomena described by quantum theory, then we should abandon the principle of distributivity, substituting for classical logic the quantum logic proposed by Garrett Birkhoff and John von Neumann.

Another paper of the same name by Michael Dummett argues that Putnam's desire for realism mandates the law of distributivity. Distributivity of logic is essential for the realist's understanding of how propositions are true of the world in just the same way as he has argued the principle of bivalence is. In this way, the question, "Is Logic Empirical?" can be seen to lead naturally into the fundamental controversy in metaphysics on realism versus anti-realism.”[10] (bold and bold italic not in original)

If one is a realist about the laws of logic, logic cannot be empirical, so not about the world in that sense.

The word "world" is ambiguous.

- 🌏 Extending even further than things that exist in spacetime are possible non-physical abstract objects, such as may include laws of nature, natural kinds, universals, numbers, or abstract objects generally.

- 🌎 It can also have the broadest possible meaning of including anything that exists.

Hence, depending upon which interpretation one makes of the world, then Feige's position on the nature of philosophy can be too narrow or too broad, as we have seen.

Additionally, the conception of philosophy Feige provides is also too narrow since he holds that philosophy should not bother to include any philosophical investigations into teeth brushing or sock washing. However, such philosophical studies are possible.

Consider teeth brushing first.

So, how many teeth are in a typical human mouth? Such a question concerns individuation. Such an individuation question can interest philosophers. If we ask, how many teeth did you brush, this might require philosophical investigation about the best way to count teeth. As soon as we need to argue between competing theories of the best way of counting the number of brushed teeth, we are doing the philosophy of teeth brushing, contrary to Feige's assertions to the contrary.

Now, sock washing. A man named Fred wishes to comfort and protect his feet, so he wraps and tucks in handkerchiefs around each foot. Is Fred now wearing shoes? Suppose we argue that because we define a shoe as “an item of footwear intended to protect and comfort the human foot,” that Fred is wearing shoes. Without changing the scenario, Fred now places shoes 👞 👞 over his handkerchiefed feet. Does Fred now have shoes over his shoes? Or, is he now wearing socks with his shoes? These are philosophical questions and require a philosophical investigation because one will have to argue for a justified definition of what is a shoe or sock, and then defend that Fred's situation qualifies (or not).

Next, imagine that Fred takes off his shoes, unwraps the two handkerchiefs, and puts them into the laundry. We ask the laundry person who washes a lot of clothing what was cleaned. The launderer replies that the items are handkerchiefs. Were the things under consideration socks? We get the reply, "Absolutely not!". Is the launderer correct that in the laundry, there are no socks but only handkerchiefs? These are philosophical issues since they concern investigations into the nature of an object and under what conditions an object can and cannot be considered a sock.

Notice that if we were to ask any hard-science scientist (physicist, chemist, biologist), or soft-science scientist (psychologist, sociologist, political scientist, etc.) to investigate this sock situation, to a person, they would all say that they do not care to examine these issues. Who is left for conceptual analysis of the nature of socks and teeth than philosophers? Nobody is left; therefore, these are philosophical questions. These kinds of questions are like those of whether the external material world exists, which all of these hard and soft scientists assume is true without wanting (or needing for that matter) to bother to investigate what arguments one can provide for arguing the question either way (the external material universe either does or does not exist).

CONCLUSION: Teeth brushing and sock washing are subject matters and concepts that philosophy and philosophers could investigate.

➢ What are the broader implications of these conclusions regarding the possibilities of philosophical investigations into teeth brushing or sock washing?

When Feige holds that “the subject of philosophy is not just any arbitrary concept,” he may be just wrong. Consider that someone sets up a test of Feige's claim that philosophy does not study arbitrarily chosen concepts. Our tester randomly cuts up all concepts from a dictionary, spins them around in a hopper, randomly choosing one from said hopper. He then proclaims that no philosopher could ever investigate this concept's philosophical issues since we arbitrarily drew it from the concept hopper. Philosophers can respond, "We are going to investigate that concept anyway!". Wouldn't this tend to disprove Feige's claim that philosophy cannot consider arbitrarily chosen concepts?

As soon as scientists challenge scientific matters fundamental assumptions, they are likely doing philosophy and not just science. Let's provide an example where this happens.

Perhaps the most straightforward example is speculating on what Albert Einstein  (1879–1955) was doing when developing the Special Theory of Relativity published in 1905. Was he only doing a scientific investigation in these circumstances? Arguably, Einstein was not doing merely 'science' since there were no actual experiments done using the scientific method, but instead Einstein used thought experiments with no empirical observations. Einstein did not do any of what we think of as an application of the scientific method since he did not do any experiments or measurement-based testing of deductions drawn from a hypothesis with refinement (or elimination) of the idea based on experimental findings. One cannot, in fact, travel at light speed oneself to see what it is like to "run with the photons." So, how did Einstein proceed? He used thought-experiments. Arguably, if one uses thought-experiments, one is doing philosophy. Since his conclusions had a real impact on the best way to understand external physical reality, Einstein was also doing science when applying these ideas to real-life experiments.

(1879–1955) was doing when developing the Special Theory of Relativity published in 1905. Was he only doing a scientific investigation in these circumstances? Arguably, Einstein was not doing merely 'science' since there were no actual experiments done using the scientific method, but instead Einstein used thought experiments with no empirical observations. Einstein did not do any of what we think of as an application of the scientific method since he did not do any experiments or measurement-based testing of deductions drawn from a hypothesis with refinement (or elimination) of the idea based on experimental findings. One cannot, in fact, travel at light speed oneself to see what it is like to "run with the photons." So, how did Einstein proceed? He used thought-experiments. Arguably, if one uses thought-experiments, one is doing philosophy. Since his conclusions had a real impact on the best way to understand external physical reality, Einstein was also doing science when applying these ideas to real-life experiments.

Why have a philosophy of jazz?[edit]

All topics are inter-related just to varying degrees. Which questions a field of study, such as the philosophy of jazz, focuses on are influenced by adjacent concerns. It is easier to start with an example to get this point across, then afterward analyze the principles and features involved. A concrete example is when a philosopher challenges the perceived wisdom of jazz musicians as flawed, wrong, or false.

It isn't that most jazz musicians couldn't be mistaken about some aspect of jazz since many plausible scenarios readily come to mind proving that the majority's opinion can be false. Consider, for example, if a famous jazz musician was thought not to be gay, but later reliable and convincing evidence showed otherwise.

Of course, most jazz experts could easily be wrong about some historical facts, just like they all might believe that the Hundred Years War lasted precisely one hundred years, which it didn't (116 years), so they are all wrong. But what about the majority's opinions about the nature of jazz? Surely they couldn't all be wrong about some essential component of what makes jazz be jazz!

But first, why not? Of course, too much philosophical weight is placed on the phrase "essential component." Is there any such thing in jazz as something essential? What exactly is that? Is essential here meaning a sufficient condition? Is it a necessary condition? Which is it?

Without some explication of what is meant by "essential component," the question asked using it is empty and cannot possibly be answered, nor do we need to address it until we know which essential component, how it is essential (sufficient or necessary), and justify why it is necessary for jazz?

Second, scenarios are easy to envision, where most jazz musicians could have flawed judgments about a musical performance. Imagine that Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie are transported back in time to 1920 New Orleans. Ragtime is all the rage. How would the majority of Dixielanders from 1920 judge Parker and Gillespie's Bebop performances? We know the answer to this question because as sophisticated musically as Louis 'Satchmo' Armstrong was, one of the music's most outstanding and renowned improvisers in the 1960s, and not 1920, is reported to have said that Bebop sounded like Chinese music to him. Presumably, what this meant was well described by Stephen Sweeney in his blog BeBop is Vulgar Music:

“We have associated Eastern music with something that is different and, often, strange. Bebop was a strange form of jazz, and it was easy for listeners to describe it as Chinese with a negative connotation, labeling it strange and foreign, and perhaps unpleasant to listen to.”

Topics and concerns for a field of study will overlap other disciplines far afield from each other's interests. Hence, what determines the area of research lies in how these interests overlap and significantly interact.

Philosophers of jazz often take their questions about jazz from questions that arise in textbooks on jazz's history and development. What are the practices of jazz itself? What investigative problems in jazz remain regardless of one's knowledge about how to play jazz? For example, musicians may not have developed views on what constitutes an improvisation versus a composition.

Let's explore this. If a musician had previously played each phrase used in an improvisation and in that order, could this new solo still count as an improvisation? Suppose you are a saxophone player who is improvising to the same song with the same musicians and rehearsing that song with an improvised solo, striving to have the same improvisation each time. Undoubtedly, each improvised solo, even when the musician tried to reproduce them precisely the same way, would not sound exactly and entirely alike. Suppose someone had done this ten times. Five of the solos are pretty close to each other in overall presentation, but the other five have some small but significant variations in notes, tones, structures, and so forth.

What should we say about these ten improvised solos? Should we say that five of them are the same solo, but the other five differ enough from each other so that the other five are different improvisations? Is each of them a composition or only the first one that Biff then tried to play the same way nine more times?

Are the answers to these questions ultimately arbitrary, so any answer we give is as right as any other? Is this how our value systems work when judging the quality or originality of an improvised solo? Were all ten solos by Biff equally valuable, or was the first one that he modeled all others on more valuable because it was first?

There are plenty of artistic achievements where it is crucial whether you did it first or not. Minimalist paintings are more valued if these were the earliest successful minimalist paintings. Nowadays, if one did the same type of painting, theorists would criticize it as passé and with very limited aesthetic interest.

These are just some of the questions that one might ask, and musicians are likely not to be concerned about the answers. Does it make any difference whether we say there are ten different solo improvisations or only one with variations?

Well, it could make a difference if you were getting paid to improvise ten different solos, and you more or less played the same solo ten times.

Is jazz/rock fusion a sub-species of jazz or not? What differences would it make if we decided the question either way? Is it just arbitrary what answer we give? Why or why not? Does playing jazz/rock fusion help answer the question of how much jazz does a jazz/rock fusion performance contain?

What is the relationship that Latin jazz has to regular jazz? Is this a musical or philosophical question, or both? What is philosophical about questions relating Latin jazz to straight-ahead jazz?

In Teorema, Julián Marrades Millet breaks down significant topics in the philosophy of music in his "A View on the Philosophy of Music," as pursued in Western philosophy over the last several decades.

“If we limit ourselves to the major topics that have been the focus of discussion in recent decades, we can group such topics into at least six main areas:

(1) Methodological issues concerning research on the philosophy of music (the debate on the definition of music; the choice of a theoretical framework to deal with the analysis of musicality; the difference between noises, sounds, and tones; the debate between objectivism and subjectivism about musical phenomena; the opposition between `pure' and 'impure' music, etc.);

(2) Ontology of music (the clash between nominalism and idealism regarding the relationship between a musical `work' and its tokens or 'performances'; the controversy between fictionalism and realism, etc.);

(3) aesthetics of music (the basic properties of music; functionalist vs. culturalist theories; the distinction between `pure' and 'impure' music);

(4) Semantics of music (the semiotics of musical meaning; the link between music and text; the distinction between structure and content; the controversy between representationalism, expressivism, and formalism, etc.);

(5) Nature of musical experience (psychological, cognitive, and moral aspects of musical experience; musical expressiveness; skills and behavioral responses involved in musical understanding, etc.);

(6) Value of music (what makes musical experience valuable; what connections can be established between music and mysticism, between music and ineffability, between music and noise; between music and silence, etc.).[12] (bold not in original)

Because these are the current and contemporary topics theorists pursue in the philosophy of music, it is easy to ask them again, yet more specifically focusing on jazz.

(1) Jazz's methodological issues: what is the definition of jazz?; can jazz even be defined?; what are the implications if jazz could not be defined?;

(2) Ontology of jazz: what musical work status do jazz performances and particularly jazz improvisations have as musical works?;

(3) Aesthetics of jazz: the basic properties of jazz; what makes for good and bad jazz traits?; are jazz improvisations inherently inferior to well-developed non-improvised compositions?;

(4) Semantics of jazz: how is emotion expressed in jazz?; are there links between jazz interpretations and meaning?; how can there be storytelling in jazz?;

(5) Nature of jazz experience: what can cognitive science discover about performing and especially about improvising jazz musicians?; what do jazz musicians need to understand to play jazz well?;

(6) Value of jazz: what makes jazz valuable?; how to rate quality improvisations;

If a philosopher of jazz argues that two jazz songs can be performances of the same musical work, or the same musical score, or that two improvised performances can be of the same music, then any theories that dispute this need to be confronted and the arguments commence. That's why philosophers of jazz concern themselves with issues of song identity.

Regardless of any particular position taken on song identity, the interest remains for a jazz philosopher because jazz musicians play songs. It can be as simple as that. The concepts and theories that consider significant components of jazz and its performances we should include in philosophy of jazz investigations.

What are foundational concepts of the philosophy of jazz if song (see Ontmusic3. What is a song?) counts as one of them:

- performance

- work of music (see Ontmusic1. What is a musical work?)

- nature of improvisation (spontaneous composition) (see PoJ.fm's articles at Ontology: Improvisation, especially Ontimpr1. What is improvisation?, Ontimpr10. Improvisation and Composition, Ontimpr7. Can Improvisation be taught?, Ontimpr11. Is Improvisation Essential to Jazz?, and Ontimpr9. How two substantial jazz improvisations could be identical)

- flow state while playing jazz

- embodied cognition and distributed cognition in performances in duos, trios, quartets, quintets, sextets, septets, octets, and even dodecahedronets, etc.

- playing music

- what is music? (see Ontmusic0. What is music?)

- how does culture come into play in music production?

- how does culture relate to the evaluations (good or bad) of qualities in music?

- when not to play

- good and bad ways to improvise (see Ontimpr12. Positive Evaluations of Good Improvisations)

- how do improvisations relate to being compositions (see Ontimpr10. Improvisation and Composition)

- can improvising be taught (see Ontimpr7. Can Improvisation be taught?)

- are improvisations inherently aesthetically inferior to pre-composed music? (see Ontimpr2. Is the best improvisation inferior to the best composition?)

- what are mistakes, and can they occur during improvisations? (see Ontimpr3. What is a mistake?, and Ontimpr4. On mistakes and improvisation)

- types of jazz and their relationships to each other (see Ontology: Types of Jazz)

- issues regarding definitions (see PoJ.fm's articles at Ontology: Defining Jazz, especially Ontdef1. What is a definition?, Ontdef2. Arguments for the impossibility of defining jazz, Ontmeta8. On the impossibility of definition, Ontdef4. Unhelpful definitions of jazz.)

- what is jazz? (see PoJ.fm's Ontology: Defining Jazz, especially Ontdef3. What is the definition of jazz?, Ontdef4. Unhelpful definitions of jazz)

- can jazz be defined?; why or why not? (see Ontdef2. Arguments for the impossibility of defining jazz, Ontmeta8. On the impossibility of definition).

A key recommendation made by the Institute for the Public Life of Arts and Ideas white paper on successful higher education policy was to make philosophy graduate student's intellectual work made public: White Paper on the Future of the Ph.D. in the Humanities

“One way to rethink graduate education is by way of this Kantian idea of the inherent public character of scholarship. We propose that students’ work should become more public and more oriented toward the world. Publicity confers a measure of relevance and permanence on the work students do. Their most accomplished research should . . . move beyond the seminar room and the library into a potentially innumerable readership and into a space of discourse oriented toward futurity. The work should, in principle, join with other work in ongoing conversations about matters of public concern.”

A possible way to achieve this goal is to write and edit for PhilosophyOfJazz.net (PoJ.fm)! Although it is harder to prove that you, a particular person, and actual author produced this work because no authorship names are permitted on (most) PoJ.fm pages. Nevertheless, for resumes, C.V.'s, seminars, and so forth, one CAN establish and justify authorship by the following means. First, you claim that you were the original author of this particular section or sections of PoJ.fm, and furthermore because the software keeps track of every editor and when that person wrote what each minute of the day by looking at this history, one could establish one's authorship of content in new sections and put it into a report, if necessary.

In his seminal paper, "Why Does Jazz Matter To Aesthetic Theory," Robert Kraut, explains that jazz is a musical art form. Aesthetic theories, whatever they are, must contain all art forms in their theorizing. Therefore, aesthetic theory must include jazz in its purview.

He points out that we need both to know what aesthetic theory is supposed to explain and what kind of music jazz consists of:

“So we need to know more about what an aesthetic theory is supposed to do—what sorts of questions it is intended to answer, what sorts of explanations and/or justifications it is supposed to provide. We also need to know more about what sort of music counts as jazz.”[13]

So, right here, we have a justification in aesthetics for investigating the philosophy of jazz.

Why do we need to find out "what sort of music counts as jazz"? Kraut justifies this investigation by explaining that "Jazz performances are part of the data, and thus part of the tribunal by which aesthetic theories must be tested and evaluated."[13]

Furthermore, it is the music of jazz we wish to investigate. What makes it tick musically, and how does it relate to other forms of music? What's so special about jazz as a form of music?

Parallels between philosophy of physics and philosophy of jazz [edit]

To provide an overview of the state-of-the-art in the philosophy of jazz, these can be specified as the central tasks.[14] First, the philosophy of jazz concerns itself with the interpretation of theories about jazz, which in many cases can inform philosophical discussions, e.g., on improvisation, composition, the status of free jazz, or requirements for works of music. Second, jazz's philosophy concerns itself with ‘foundational issues' in fundamental jazz, regarded as the most exciting and vital problems in the field. In contemporary textbooks and collections on the nature and properties of jazz, they raise important questions that need addressing.

Philosophers of jazz don’t just accept what musicians might say about jazz; a large part of their job is to interpret the theories about issues surrounding and related to jazz and assessing the merits of competing points of view. Additional tasks for jazz philosophers: they consider the epistemic claims made by musicians and theorists, which often involves the critical reflection on naive beliefs, contributing to the foundational development of jazz theories.

However, it is not always entirely clear, first, what exactly is meant by interpretation and, second, why interpreting theories should be of genuine interest only to the philosopher of jazz and not so much to jazz musicians. However, there is a difference in that jazz performers are often much more pragmatic than philosophers of jazz in ignoring theoretical issues so that they can go about and get on with playing the music.

The philosophy of jazz explores fundamental issues in philosophy, especially in aesthetics, methodology, fundamental concepts, social and political philosophical problems, and jazz's epistemology and ontology. Philosophers of jazz may ask methodological questions about how musicians acquire knowledge about jazz. For example, to what extent do college-educated players all sound alike compared to players from the school of hard knocks. Secondly, they have a conceptual interest in elaborating and clarifying the meaning of central concepts in jazz, such as musical works, improvisations, or race and gender issues in jazz history. The third main task for philosophers of jazz is to formulate and evaluate suitable ontologies for specific jazz definitions. Since—in contrast to general philosophy—these ontologies are always tailored towards a given jazz theory, they can be characterized more precisely as a mapping of some aspects of the given theory to entities (e.g., songs, improvisations, freedom or which sub-genres we should or should not include under the species of jazz), to which the theory is supposed to contain or exclude. We can categorize the basic types of entities using general features, such as definitions, musical practices and conventions, or relations between jazz sub-genres. Ideally, we define a primary type by specifying a set of necessary features sufficient for membership in that category. Moreover, comprehensive ontologies for a given jazz theory are usually required to be parsimonious and empirically adequate. One should posit as few types of basic entities as possible to understand how the theory describes the world. All predictions based on the ontology should agree with empirical results.

Although the described meta-issues do not belong to most jazz musicians' core preoccupations, repeatedly in the history of jazz, such as methodological, conceptual, and ontological questions are often in the forefront. Is Bebop jazz? Is free jazz really jazz? How much jazz does jazz/rock fusion contain?

The boundary between jazz practices of musicians and the philosophy of jazz is blurry. The philosophy of jazz takes jazz knowledge as its starting point but sometimes also contributes to philosophical understanding. The distinction between jazz practices and the philosophy of jazz is particularly unclear concerning foundational questions.

The philosophy of jazz is interested in foundational problems of jazz theories. Philosophers of jazz show a vivid interest in conceptual ambiguities or even inconsistencies between jazz theories. For instance, philosophers of jazz deeply engage in debates regarding the possibility or impossibility of defining it, with many defenders on both sides. Of course, such problems are sometimes addressed by jazz players, such as Dave Liebman or Derek Bailey, though much more rarely, particularly if taking into account the total number of jazz players versus the much more limited number of jazz philosophers.

Philosophers of jazz often engage in inquiries that are similar to those of theorists in general working during periods of musical crises, such as the neo-conservative views on the nature of jazz supported by Wynton Marsalis. During a conceptual crisis, philosophers of jazz become concerned with foundational issues, they abandon or at least question essential parts of the respective former theoretical positions regarding jazz elements and thus choose to leave the previous theories. At this point, they view conceptual problems as genuine anomalies that are most likely not solvable by conventional means within the orthodoxy of a paradigm. Philosophers of jazz share this critical attitude with regard to the foundations. It thus comes as no surprise that the arena of the philosophy of jazz has characteristics that Thomas Kuhn describes for science in crisis: the existence of different schools, the lack of agreement between these schools in particular concerning metaphysical assumptions, the interest in questions of method, the willingness to address an audience beyond its own limited academic philosophical community and enter into outside areas including cognitive science, neurology, social practices in jazz, gender studies, technological influences, legal issues regarding intellectual property rights regarding music, etc.

A pluralistic, non-partisan approach to concepts and theories is adopted by the philosophy of jazz. While many jazz theorists tend to be stubborn about its basic assumptions or at least pragmatic about neglecting alternatives that are not in any important way better than the orthodox ones, philosophers of jazz are deeply interested in assessing alternative approaches. Indeed, the philosophy of jazz literature contains numerous discussions of alternative theories. Philosophers of jazz habitually talk about and take seriously whether musical works are abstract objects pre-existing before discovered by composers or not. Moreover, philosophers of jazz are vividly interested in how fundamental notions change in theoretical contexts. For example, are jazz improvisations entirely spontaneous or not? If a musician has practiced a lick and then includes it in her solo, was it wholly spontaneous or not?

Striving to be accurately historically informed is another goal of the philosophy of jazz. This issue closely connects with the previous one. If the outlook of jazz philosophy is generally pluralistic, then we should ensure that we take all plausible competitors to a theory into account. Often, the quality and soundness of arguments depend on this. Since human imagination is unfortunately quite limited and the elaboration of alternatives seems to require several people's concerted efforts over a relatively long time, we must consult all available sources for other options. Of course, the largest repository is in the history of jazz and jazz theory. Historical knowledge is indispensable, if we are to assess the spectrum of conceptual and methodological possibilities. Again, this fits well with observations regarding jazz practice. While philosophers of jazz habitually engage with historical works and a number of them even carry out historical studies themselves, the historical ignorance and the frequent reference to historical pseudo-accounts in jazz textbooks are lamented.

Philosophers of jazz make normative claims about jazz methods and are interested in the scope and limits of jazz knowledge. It is a truism that one can often learn at least as much from failure as from success, which also holds true concerning jazz hypotheses and theories. The interest in alternatives puts the philosopher of jazz in an excellent position to assess jazz methods' claims and evaluate methodological arguments within jazz. If a theory makes good predictions, what can this tell us about the jazz universe?

Jazz philosophy keeps an eye on the social boundary conditions of jazz research striving to situate jazz within the broader spectrum of human knowledge.[15] One must at least consider the possibility of social factors to influence the development of jazz. To be sure, this is not to say that social factors necessarily play a role in the development of jazz. Instead, an assessment of jazz, if it wants to be complete, has to consider the possibility that external factors like broader social and ideological conditions or the psychology of influential musicians and jazz theorists have a lasting impact on jazz.

The need for multimedia argumentative platforms and delivery vehicles[edit]

When commenting upon and comparing the two music documentaries titled "Rock and Roll" (produced by the BBC) and the American produced Ken Burns's "Jazz," reviewer David Shumway remarks on the persuasive power these multimedia presentations have, including still pictures, panning/motion of still pictures (actually named after Ken Burns), black and white as well as color imagery and videos, flashy graphics, superior voice-overs, stimulating interviews, and so forth) that more traditional past academic practices of primarily arguing with words on paper places academics at a disadvantage for convincing the masses of correct explanations and appropriate conclusions.

“These [e.g., Ken Burns's "Jazz"] popular or "middle brow" interpretations compete with academic ones, and are likely to do so successfully since they can combine images and music with the verbal analysis that is the only medium in which the academic typically works. The role that these multimedia productions play in contemporary intellectual life is a marker of postmodernity. The printed word is losing its role as the primary form in which culture is interpreted and history is narrated. Thus, I am interested in understanding not only what these documentaries say, but also how they say it—in part to begin to think about how cultural studies might be able to use this medium for its own ends (should the present financial barriers ever be lifted). So far, academics have managed to make use of the visual possibilies of digital and electronic media only to a limited extent, mainly in the form of supplements to textbooks. But if Cultural Studies is to reach an audience beyond the academy, it will need to exploit these media much more fully in the future.”[16] (bold and bold italic not in original)

Heeding this advice, PoJ.fm embraces this more inclusive multimedia approach for delivery of academically oriented materials, as advocated by Shumway. Furthermore, the power of the computer combined with the internet provides great power and resources for intellectual connections because of the ability to interconnect myriad topics and relevant materials using hyperlinks that Shumway does not mention during his review. By incorporating hyperlinks, a text gets supercharged and becomes itself hypertext. The numerous advantages of hypertext and hypermedia are immediately apparent and welcomed by anyone seeking instant access to information and explanations of concepts, word meanings, images related to text, animated gifs, and access to all that an integrated internet of information is capable of making spontaneously available at a user's clicking on any area of interest. This approach enables the easy-to-use publication of information over the Internet making it publicly available to anyone with computer access.

Besides having immediate access to individual pieces of information, users can pursue their individual interests at progressively multiple levels of detail, skipping over already familiar and understood concepts, theories, or ideas, and tackling material at any depth from superficial, shallow overviews back down into arcane, complexified, or mystifying topics of their immediate concerns.

Hypertext and hypermedia provide users with easy and convenient access to data of immediate concerns permitting quick learning and/or surveying a field of study or area of interest. A reader can pursue with unprecedented freedom choosing what part of the whole he or she wishes to read next, as well as how the system should behave with respect to the reader's choices and manipulations of hypergraphics.

It is not only text that can be hyperlinked, but also many other forms of data such as links to tables, images, videos, music, and other presentational content formats with integrated hyperlinks.

The hypermedia approach also comes with a lot of pop and pizzazz from beautifully colored and vibrant images, titles, text, and motion. Dynamic, interactive, shiny, colorful presentations will usually be much more entertaining, more informative, and easier to recall than duller static presentation mediums as in traditional academic journal articles. Computerized hypermedia certainly has all of these excellent features. Hypergraphics creates multidimensional explorable pictures and media potentially having interaction between itself and a user. Ultimately, hypersystems are ones where users can explore complex information at their own pace and in their own way.

By having material linked together via a computerized internet enables non-sequential organizations of information. This permits users to browse among non-sequentially organized anything, jumping to new or unrelated areas of interest as the need or use of unrelated material catches the attention of a user. Additionally, users can now edit, annotate, reply to, comment upon material that can later be accessed by others or even by oneself. Such annotation capacities can lend new clarity as well as justifications or criticisms and objections to previously established material and texts thereby advancing knowledge.

Why use hypertext?[edit]

Coiner of the term hypertext in 1963,[17] founder and promoter of the hypertext discipline is Theodor H. Nelson (b. 1937).[18]

He presciently realized before computerized hypertexting was possible (could occur now) much of what has come to fruition via the world wide web and the internet. Nelson conceives of hypertext as, by definition, non-sequentially linked information. Of course, this does not prevent such hypertext from still having sequentially based information as well, nor does hypertext require any computers or computerized linkages. In the quotations below, Nelson provides non-computerized examples of hyper-text including some magazine layouts or the front pages of newspapers as qualifying as hyper-text.

“By hypertext, I mean non-sequential writing—text that branches and allows choices to the reader, best read at an interactive screen. As popularly conceived, this is a series of text chunks connected by links that offer the reader different pathways.”[19] (bold not in original)

“HYPERTEXT DEFINED: By hypertext I simply mean non-sequential writing. A magazine layout, with sequential text and inset illustrations and boxes, is thus hypertext. So is the front page of a newspaper, and so are various programmed books now seen on the drugstore stands (where you make a choice at the end of a page, and are directed to other specific pages). Computers are not intrinsically involved with the hypertext concept. But computers will be involved with hypertext in every way, and in systems of every style. (Ideally, you the reader shall be free to choose the next thing to look at—though repressive forms of hypertext do turn up.)”[20] (bold and bold italic not in original)

“Extending the notion slightly, we get windowing hypertext—where nonsequential writings—hypertexts—window to other stored materials. It is this notion, then, of windowing or compound hypertext—which we foresee as the vital and basic new information system of the future—that has charged and inspired the present work.”[20] (bold and bold italic not in original)

Nelson, once having discovered the fundamental power of the ability of hypertext linking and its capacity to be used non-sequentially, put a lot of thought into how this could work and how it compared to earlier informational delivery systems that for practical purposes, according to Nelson, had to proceed so as to be organized and presented sequentially.

Nelson has a lot of opinions about the strengths and weaknesses, the advantages and disadvantages, of informational systems fundamental structure being sequentially or non-sequentially presented.

As philosophers we are obligated to investigate, explore, and develop these conceptions of sequencing being referred to so often. The intuitive idea is fairly clear. A sequential presentation proceeds in an orderly manner with first things first and third things third. Non-sequential sequencing permits the second thing be investigated by the user prior to investigating the first thing.

➢ What makes information be in a sequential presentation? What is it that achieves the relative ordering of the information presented?

While there is no absolute answer available to humans the fundamental assumptions are that the information be presented in an orderly manner. Again, what determines this order will vary, but to provide a more concrete sense of such an ordering consider how students are often instructed in how to present an argument or a paper with arguments. The order can be, first, you tell the reader what it is you will be attempting to prove, then you prove it, next you might consider objections to the conclusion in the reasoning used to derive it, lastly, you review and summarize how you proved it and what it's significance is given that it is true. Put simply, first you tell them what you are going to tell them, then you tell them, and lastly you tell them what you told them. This is a sequential ordering for an informational presentation. Were one first to consider an objection to your thesis the reader would not yet have necessarily been convinced that the thesis you are now objecting to is true in the first place so it would be out of place to start a paper or talk this way without generating confusion, consternation, befuddlement, and quite probably annoyance in your readers or audience. Still, suppose the reader already is convinced of the main thesis and her first interest is to see how the presentation addresses this particular objection. If this were the case then going out of order could be appropriate because it is what the reader wants to investigate first. Here is how hypertext linkings can be appropriately out of order and still be useful and practical.

Ted Nelson Quotations on hypertext[edit]

“Unfortunately, for thousands of years the idea of sequence has been too much with us, because nothing else has been practical; and indeed, creating a system subtle and profound enough to meet our real needs has proven to be an extensive task indeed. The structure of ideas is never sequential; and indeed, our thought processes are not very sequential either. True, only a few thoughts at a time pass across the central screen of the mind; but as you consider a thing, your thoughts crisscross it constantly, reviewing first one connection, then another. Each new idea is compared with many parts of the whole picture, or with some mental visualization of the whole picture itself. It is the representation of whole structures of ideas, and placing them on the page for others to understand, that we call writing. Writing is the representation and the presentation of thought.”[21] (bold and bold italic not in original)

(So are pictures and diagrams; but they are intrinsically nonsequential, and so not relevant to the present argument.)[21] (bold not in original)

Computer presentational media, coming soon. will not be technically determined but rather will be new realms for human artistry. This point of view radically affects how we design man-machine systems of any kind, especially those for information retrieval, teaching, and general writing and reading. Some practitioners see such systems as narrowly technical, with the computer hoisting up little pieces of writing on some "scientific" basis and showing them to you one grunt at a time. A Metrical banquet. I disagree. The systems should be opulent.[22]

3) The problem in presentational systems of any kind is to make things look good, feel right, and come across clearly. The things that matter are the feel of the system, the user's state of mind, his possible confusion, boredom or enthusiasm, the problems of communicating concepts, and the very nature of concepts and their interconnection. There will never be a "science" of presentation, except as it relates to these things.[22]

4) Not the nature of machines, but the nature of ideas, is what matters. It is incredibly hard to develop, organize and transmit ideas, and it always will be. But at least in the future we won't be booby-trapped by the nature of paper. We can design magic paper. It is time to start using computers to hold information for the mind much as books have held this information in the past. Now information for the mind is very different from "information for the computer" as we have thought of it, hacked up and compressed into blocks. Instead we can stretch the computer.[22]

I am proposing a curious kind of subversion. "Let us design," I say; and when people see the systems, everybody will want one. All I want to do is put Renaissance humanism in a multidimensional responsive console. And I am trying to work out the forms of writing of the future. Hypertexts.[22]

Hypertexts: new forms of writing, appearing on computer screens, that will branch or perform at the reader's command. A hypertext is a non-sequential piece of writing; only the computer display makes it practical. Somewhere between a book, a TV show and a penny arcade, the hyper-text can be a vast tapestry of information, all in plain English (spiced with a few magic tricks on the screen which the reader may attack and play for the things he wants, branching and jumping on the screen, using simple controls as if he were driving a car. There can be specialized subparts for specialized interests, instant availability of relevancies in all directions, footnotes that are books themselves. Hyper-texts will be so much better than ordinary writing that the printed word will wither away. Real writing by people, make no mistake, not data banks, robot summaries or other clank. mA person is writing to other people, just as before, but on magical paper he can cut up and tie in knots and fly around on.[22]

“'Hypertext' is a recent coinage. 'Hyper-' is used in the mathematical sense of extension and generality (as in 'hyperspace,' 'hypercube') rather than the medical sense of 'excessive' ('hyperactivity'). There is no implication about size—a hypertext could contain only 500 words or so. 'Hyper-' refers to structure and not size. (Theodor H. Nelson, "Brief Words on the Hypertext," January 23, 1967)

The English prefix "hyper-" comes from the Greek prefix "ὑπερ-" and means "over" or "beyond"; it has a common origin with the prefix "super-" which comes from Latin. It signifies the overcoming of the previous linear constraints of written text.

The term "hypertext" is often used where the term "hypermedia" might seem appropriate. In 1992, author Ted Nelson—who coined both terms in 1963—wrote:

- By now the word "hypertext" has become generally accepted for branching and responding text, but the corresponding word "hypermedia", meaning complexes of branching and responding graphics, movies and sound—as well as text—is much less used. Instead they use the strange term "interactive multimedia": this is four syllables longer, and does not express the idea of extending hypertext.” (Nelson, "Literary Machines," 1992) [23]

What are the advantages of using hypertext?[edit]

In October, 1962, researcher Douglas C. Engelbart published his own version of Vannevar Bush's vision as represented in Bush's 1945 paper, "As We May Think," wherein Engelbart describes an advanced electronic information system in "Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework." Engelbart prepared this as a summary report of his research for the Air Force Office of Scientific Research and Development. In this report Engelbart describes the non-sequentiality of hypertext.

“Most of the structuring forms I'll show you stem from the simple capability of being able to establish arbitrary linkages between different substructures, and of directing the computer subsequently to display a set of linked substructures with any relative positioning we might designate among the different substructures. You can designate as many different kinds of links as you wish, so that you can specify different display or manipulative treatment for the different types.”[24] (bold and bold italics not in original)

Problems for defining jazz[edit]

➢ Problem 1: How should we understand the African and European influences in music and how they amalgamated within jazz. Was it primarily or exclusively the originally African-oriented musicians responsible for incorporating European music into their African music, or was it the other way around? Or, was it a joint and mutual venture where one should not give any precedence to one over the other regarding priority. For PoJ.fm's take on these issues, see PoJ.fm's Ontdef3. What is the definition of jazz? How jazz differs from African and European musical influences.

This balanced point of view appears to be contravened by Thomas E. Larson's assertion in the following quotation from his textbook Modern Sounds: The Artistry of Contemporary Jazz that it was Africans who incorporated European musical elements into their African music. Additionally, Larson believes that the abundance of slaves and people of color, especially Africans in the Southern states, accounts for why early jazz was not found in the Northern cities and states.

“The incubation period for the creation of jazz goes back to the very beginning of slavery in early 1600s. It was only after nearly 300 years of the two musical traditions-African and European-coming in contact with each other that the birth of jazz took place. It is important to remember that it was 19th century African-Americans who were motivated for various reasons (discussed in chapter 2) to incorporate elements of European music into their own musical tradition. This is why jazz was born in New Orleans and other cities in the south, not in the northern states.”[25] (bold and bold italic not in original)

Objection to the claim that all early jazz came from New Orleans and only Southern cities of the United States: That early jazz came exclusively from Southern cities is doubtful. Is Iowa, or Duquesne, Pennsylvania (twelve miles south of Pittsburgh) or Toledo, Ohio, in the South, which is where early jazz greats Bix Beiderbecke (1889–1940), Earl Hines (1903-1983), and blind pianist Art Tatum (1909–1956) are from. So, no, not every early jazz musician of renown originated from the Southern United States.

If by early jazz we mean 1915–1920, jazz existed then in northern and non-Southern cities, including Chicago, Detroit, St. Louis, Kansas City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, etc.

➢ Problem 2: What problems and objections are there to using only a guidelines approach for characterizing which music exhibits jazz? Can a grab bag approach succeed in defining and describing jazz as Thomas E. Larson does in his textbook, Modern Sounds: The Artistry of Contemporary Jazz. Larson finds it practically impossible to define jazz because jazz “is performed in so many styles, and its influence can be heard in so many other types of music [making it] nearly impossible to come up with a set of hard and fast rules to define jazz.”[26]

Larson, therefore, suggests an alternative to supplying hard and fast rules for jazz and “instead, to define jazz, it is helpful to think of a set of loose guidelines that are followed to one degree or another during the course of a jazz performance. Here are five basic guidelines: (1) Improvisation, (2) Rhythm, (3) Dissonance, (4) Jazz Interpretation, and (5) Interaction.[27] For further discussion on Larson's proposed definition for jazz, see PoJ.fm's Ontdef3. What is the definition of jazz? Assessment of Thomas E. Larson's characterization of jazz.

Let us consider these five guidelines in turn. Improvisation cannot exclusively define jazz because non-jazz music, including the blues, country, rock and roll, and classical Indian music, uses improvisation regularly during performances. No rhythm is unique to jazz. Furthermore, blues and rock use syncopation during performances, among others. Many kinds of music besides jazz use dissonance and have individualized sounds. Musicians use distinctive sonic inflections in cajun music, zydeco, blues, and even heavy metal to communicate emotions and other things. Nor is one permitted to define jazz as including the concept of "jazz interpretation"; otherwise, one explains something in a non-helpful circular manner. Lastly, as even Larsen points out, interaction is used by all musicians when playing in non-solo settings. It is not distinctive to jazz.

Larson could reply that his guidelines approach is not claiming any one of these factors is unique to jazz, but rather that his five factors together are sufficient for jazz to occur.

Is this true? Is there some other non-question begging way to describe the jazz interpretation feature? One might try using specific musical interpretation strategies, such as using a circle of fifths or being prepared to play the same song in all twelve keys and capable of switching between keys during the same song. Given this reading of "interpretation," then all five guideline features can be present in non-jazz music such as the blues, although the blues musician generally does not run the same song through all twelve keys.

Larson might defend his five guidelines by claiming that jazz musicians use these five guidelines properties in greater proportion than other music uses them. Unfortunately, this too seems false, as well as difficult to quantify. Do blues musicians improvise more or less than jazz musicians? Probably rappers improvise a lot compared to any previously prepared music. Hence, it is false that jazz musicians improvise significantly more than non-jazz musicians, or use types of rhythm or interpretation or interaction not also found in non-jazz genres.

Dissonance can undoubtedly occur in rock and roll music, such as when Jimi Hendrix uses feedback and a distorting whammy bar. Heavy metal music can have dissonances. Everybody in all forms of music incorporates interpretations of varying sorts—that by itself, with such an under-developed and non-descript characterization for 'interpretation,' can be had by non-jazz musical genres as well.

How about rhythm, dissonance, or musical interpretation and individualized musical expressions or group interactivity? Again, many non-jazz kinds of music have all of these features and often to a high proportion. There can be a lot of dissonances, to say the least, in a hardcore punk band's performance.

Objection to a loose set of guidelines approach for defining jazz: A flexible set of guidelines, or grab bag approach, is just too weak for satisfactorily characterizing and defining jazz.

Justify with an explanation of why it is not satisfactory if the musicians do not care why should anyone care? Is this an important question?

Suppose a better definition picks out all and only jazz with some degree of margins for error. Such a definition would be an improvement over a looser set of requirements that cannot pick out all and only jazz or that has a higher margin for error. It is rational to prefer a definition that captures either more of the phenomena or more accurately categorizes it.

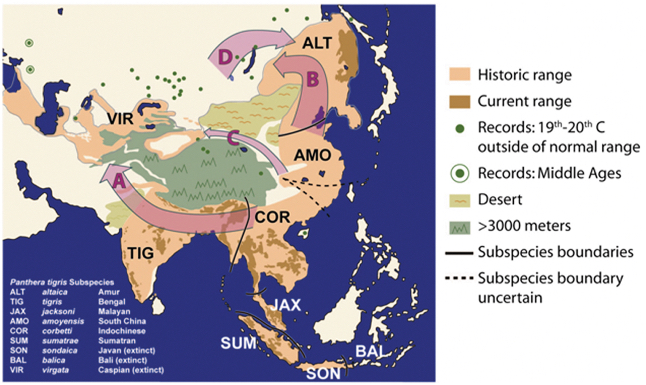

Everyone should prefer the description of tigers in definition (T1) for determining what is a tiger 🐅 over definition (T2).

- (T1) A tiger is a solitary and territorial large carnivorous orange and black striped predatory mammal (although some are golden (few or no stripes), and some are white such as Bengal tigers) with a white underside and a powerful body, strong forelegs, large head, and a long tail.

- (T2) A tiger is a large striped animal found in India, Russia, China, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand, Myanmar, Nepal, Cambodia, Asia, Sudan, and Brunei.

Both definitions are highly detailed, and each has information that the other one lacks. Why then prefer, or commend as superior, the first one (T1) with a better description of the traits of the animal itself over (T2) that emphasizes a tiger's natural habitats currently found on planet Earth. Answer: because this is what we wanted to know about when asked to define tiger. We were not asking the more specific question of where are a tiger's habitats, which is a secondary characteristic and not limited to future expansions or demotions of the species' locales.[28] The tiger's internal non-geographical properties are much more likely to remain stable over time making them more suitable for identifying the object under question, as also for jazz. A better definition for jazz includes the properties making music be jazz and not just, say, the locations where jazz can be found, as in the tiger example. For more discussion on this topic, see PoJ.fm's Ontmeta8. On the impossibility of definition: Musical genres cannot be defined using ONLY geographical or biographical information.

➢ Problem 3: QUESTION: Could jazz have an essence? If jazz has no essence, then what is holding it together? How does the music itself contribute to what music is jazz? Suppose someone held that the musical properties of jazz are irrelevant for defining it since it doesn't have any essence to begin with, as reflected in the following quotation.

“Nothing in the previous practice [of past jazz genres] signaled that certain styles, and not others, would count as jazz later. Nor is it likely that actual jazz history reflects a more principled, strategic, elegant, or otherwise defensible program than all counter-factual ones.”[29] (bold and bold italic not in original)

It might then seem to follow that if jazz lacks any intrinsic nature, it can arbitrarily be lumped in with any other kind of music and called by a new name. Suppose we call it jaqqazz (pronounced "jak-kazz"). Does jaqqazz now exist as an independent musical genre? Arguably not, and to better understand why not see the arguments against it at PoJ.fm's Ontdef3. What is the definition of jazz? What arguments prove the Nazi critics are mistaken that Bebop is not jazz? regarding "country opera."

➢ Problem 4: Can arbitrary institutions dictate what constitutes jazz as a genre of music? No, and for arguments, see PoJ.fm's Ontdef3. What is the definition of jazz? Why jazz is not just an institutionally practice-mandated musical genre.

➢ Problem 5: Are there then ANY restrictions placed upon what could constitute jazz? Yes, it has to be music. Justification: any definition of jazz that did not have that the object under consideration was a genre of music would no longer be defining what is meant generally by all competent speakers of the native English language when referring to jazz as a genre of music. For example, consider the absurdity of the situation if someone said jazz is identical to and defined as the windshield wiper's found on automobiles. Their proposed definition gets ruled out as irrelevant because jazz cannot be the same thing as windshield washers on cars. Indeed, there are several necessary conditions for playing jazz.

➢ What determines what gets excluded from being jazz? See PoJ.fm's "Ontdef3. What is the definition of jazz? How communities shape definitions?" and "Ontdef3. What is the definition of jazz? What determines when music is a type of jazz?".

➢ Problem 6: Who determines what features are and are not relevant for defining jazz? Could it be musicians? It is false that jazz musicians, while undoubtedly experts in playing jazz, need proficiency in providing an overarching characterization of what it is that they are performing as a genre of music. They do not need to be experts in philosophy or in the philosophy of jazz to be experts at playing jazz.

➢ Problem 7: Are there any experts that are already experts in the philosophy of jazz? While it is true that knowledge and expertise regarding the philosophy of jazz does come in degrees with some experts being more knowledgeable and insightful than other experts there is no one particular final word on the subject decisive experts. Here the answer is clearly that there are no decisive experts in the philosophy of jazz such that whatever this person's opinion happens to currently be determines what is true about a subject in this field of study.

➢ How can it be known that there are no decisive experts whose word is final on any particular topic that falls within the philosophy of jazz?

- ANSWER: It is because not all solutions are known for any field of study or intellectual endeavors. Humans are not omniscient, and we have to figure stuff out on our own. Even if God, an omniscient being, tells you that "All A's are B's," doesn't mean that you understand what he says. As an evaluator, even after being given perfect knowledge from an omniscient being, you have to consider and assess what this information implies, its significance, how to verify it, how to falsify it (it can only seem false since it is a factual claim made by a truth-telling omniscient being), etc. What happens if other people challenge that "All A's are B," then as philosophers we want to be able to justify and explain all sorts of possible stuff about "All A's being B's" such as why is it true, could it have been false, how does this knowledge affect your earlier views about B's, and so forth. Are there other ways to prove that "All A's are B" besides appealing to claims given by an omniscient being?

Explain the differences between a more robust and a weaker definition. The most vital definitions pick out all and only their definiens and can be used to account for why these properties delineate the domain of reference.

PoJ.fm chats with ChatGPT (January 30 2023 version) on topics in the philosophy of jazz[edit]

PoJ.fm: What philosophical questions or problems are there about jazz?

ChatGPT: There are several philosophical questions and problems related to jazz, some of which include:

- Aesthetic value: Is jazz an art form with inherent aesthetic value, or is its value a matter of cultural and personal taste?

- Improvisation: What is the nature of improvisation in jazz, and how does it relate to creativity and intentionality?

- Authenticity: What does it mean for a performance or composition to be "authentically jazz"? How does this relate to the idea of cultural appropriation?

- Musical expression: How does jazz express emotions, ideas, and experiences, and what is the role of the individual performer in this expression?

- Social and cultural context: How does jazz reflect and shape the social and cultural context in which it is performed, and what is the relationship between jazz and issues such as race, gender, and class?

These questions are still the subject of ongoing philosophical debates and discussions, and there is no widely accepted resolution to many of them.

PoJ.fm: Name more philosophical questions about jazz.

ChatGPT: Sure, here are some additional philosophical questions related to jazz:

- Musical genre: What makes jazz a distinct musical genre, and how does it differ from other forms of music?

- Improvisation and structure: How do improvisation and structure interact in jazz, and what is the relationship between improvisation and musical form?

- Jazz and tradition: How does jazz relate to musical tradition, and what is the role of tradition in jazz performance and composition?

- Jazz and politics: What is the relationship between jazz and political activism, and how has jazz been used to comment on social and political issues?

- Jazz and commercialism: How does the commercialization of jazz affect its artistic value and cultural significance?

- Jazz and cultural identity: How does jazz reflect and shape cultural identity, and what is the relationship between jazz and national identity?

- Jazz and technology: How has technology, such as recording and electronic instruments, influenced the development and interpretation of jazz?

These questions highlight the rich philosophical dimensions of jazz, and demonstrate the complexity and diversity of the genre.

PoJ.fm: Can you name more philosophical questions about jazz?

ChatGPT: Yes, here are a few more philosophical questions related to jazz:

- Jazz and intertextuality: How does jazz draw on and reference other musical forms, and what is the relationship between jazz and musical intertextuality?

- Jazz and experimentation: How does jazz embrace experimentation and novelty, and what is the relationship between innovation and tradition in jazz?

- Jazz and audience: How does the audience influence the performance and interpretation of jazz, and what is the role of the listener in the jazz experience?

- Jazz and collaboration: How does collaboration between musicians and between musicians and audiences shape the creation and interpretation of jazz?

- Jazz and musical meaning: How does jazz convey meaning, and what is the relationship between musical structure, form, and meaning in jazz?

- Jazz and musical genre boundaries: What is the relationship between jazz and other musical genres, and how do boundaries between genres influence the development and interpretation of jazz?

These questions highlight the many philosophical dimensions of jazz, and demonstrate the ongoing relevance and richness of the genre.

PoJ.fm: Are there more philosophical questions about jazz?

ChatGPT: Yes, there are many other philosophical questions that can be asked about jazz, as it is a rich and complex musical genre with many dimensions. Here are a few more:

- Jazz and cultural appropriation: How does the use of jazz elements by musicians outside of the African American community impact the cultural significance of the genre?

- Jazz and musical expression: How does jazz reflect and express individual and collective experiences and emotions, and what role does musical expression play in jazz?

- Jazz and musical improvisation: How does musical improvisation impact the structure and form of jazz, and what is the relationship between improvisation and musical composition in jazz?

- Jazz and musical identity: How does jazz shape musical identity, both for individual musicians and for the genre as a whole, and what role does musical identity play in jazz performance and interpretation?

- Jazz and musical interpretation: How does interpretation impact the performance and understanding of jazz, and what is the role of interpretation in shaping the cultural significance of the genre?

These are just a few of the many philosophical questions that can be asked about jazz, and each of them can lead to deep and thought-provoking discussions about the nature and meaning of this rich and complex musical genre.

PoJ.fm: Are there more philosophical questions about jazz?

ChatGPT: Yes, there are many other philosophical questions that can be asked about jazz, reflecting its complexity and diversity. Some additional questions include:

- Jazz and musical communication: How does jazz facilitate musical communication between musicians and between musicians and audiences, and what is the role of musical communication in jazz performance and interpretation?

- Jazz and musical creativity: How does musical creativity play a role in jazz composition and performance, and what is the relationship between musical creativity and musical tradition in jazz?

- Jazz and musical evolution: How has jazz evolved over time, and what factors have influenced the evolution of the genre?

- Jazz and musical genre classification: How is jazz classified as a musical genre, and what criteria are used to define and categorize jazz?

- Jazz and musical influence: How has jazz influenced other musical genres, and what is the impact of jazz on musical culture more broadly?

These are just a few examples of the many philosophical questions that can be asked about jazz, and each of them can lead to interesting and thought-provoking discussions about the nature and meaning of this rich and complex musical genre.

PoJ.fm: What ontological philosophical questions are there about jazz?

ChatGPT: In ontology, the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of existence and being, there are several philosophical questions that can be asked about jazz. Some of these questions include:

- The nature of jazz: What is the essence of jazz, and how is it different from other forms of music?

- The ontology of jazz performance: What is the ontological status of jazz performance, and how does it relate to the ontology of musical composition and recorded music?

- The ontology of jazz improvisation: What is the ontology of jazz improvisation, and how does it relate to the ontology of musical performance and composition?